Opposition leaders see signs President is trying to cling to power

The United States and the European Union must continue to press Congolese President Joseph Kabila to leave office at the end of his second term in 2016 because the country’s constitution bars him from seeking a third term, opposition officials from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) said March 9.

“We’re hoping the [United States and the EU] will play an important role… It’s the future of 70 million people in our country that hangs in the balance,” Vital Kamerhe, former President of the National Assembly and current leader of the Union for the Congolese Nation opposition party, told an exclusive audience at the Atlantic Council.

Kamerhe, who finished third in the last presidential election in 2011, according to the disputed official tally, is a leading contender in the contest that is supposed to take place next year.

Jean-Lucien Bussa Tongba, a National Assembly deputy and leader of the opposition Current of Democratic Renewers, said there are “two certainties” in the DRC—first, that Kabila will try to prolong his term in office at all costs, and second, that the president will yield if the international community pressures him sufficiently.

The DRC’s constitution, approved in a 2005 referendum organized by Kabila himself, limits the President to two consecutive five-year terms in office. It contains a clause that “specifically stipulates that the limit on presidential terms is absolute and not subject to ‘any constitutional revision,’” said J. Peter Pham, Director of the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center.

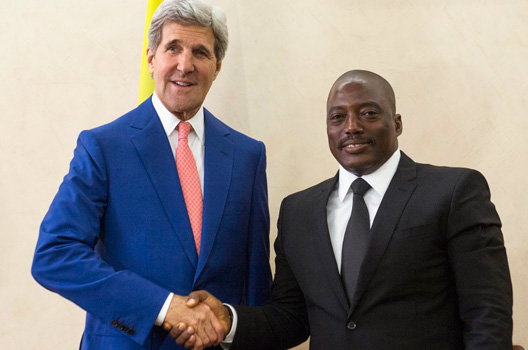

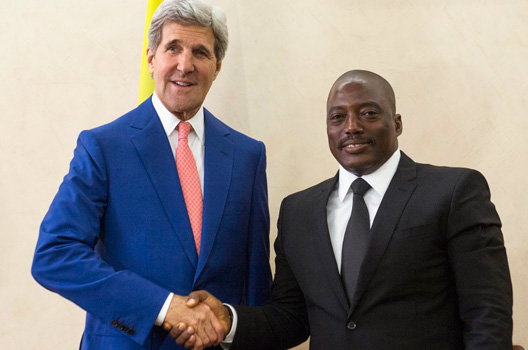

The Obama administration has made it clear to Kabila that he must respect the constitution. It sent US Secretary of State John F. Kerry to the DRC in May 2014 to urge Kabila not to seek a third term in office. Russell Feingold, US Special Envoy for the Great Lakes and DRC, echoed those remarks a month later.

Bussa welcomed Washington’s position and said other measures, like the denial of US visas to Congolese officials, should be part of the toolkit to keep up the pressure.

The United States could also use the threat of sanctions to keep the democratic process on track, said Samy Badibanga Ntita, a deputy in the National Assembly. Badibanga also chairs a parliamentary group comprising the Union for Democracy and Social Progress and its allies, the country’s largest opposition bloc.

While Kabila appears to have dropped plans to amend the constitution, he is now seeking other ways to prolong his term, including ordering a nationwide census that would take years to complete, said Kamerhe.

“The first fight that the opposition has to lead is to ensure our constitution is respected,” Kamerhe, who spoke in French, said through an interpreter.

Developments in Burkina Faso, where Blaise Compaore was forced to end his 27-year rule following massive protests in October 2014, have put longtime leaders in Africa on notice and inspired people living under their control.

Compaore’s resignation convinced Kabila to abandon his strategy to amend the constitution, said Kamerhe.

Kabila came to power in 2001 after his father, Laurent Kabila, was assassinated. International observers said the last election in 2011 was not credible.

Following protests amid fears that Kabila was trying to surreptitiously extend his term by proposing legislation to delay elections until after a census, Congolese officials in February announced that presidential and legislative elections would take place in November 2016.

But the electoral calendar proposed by the election commission does not meet the people’s expectations, and is “unrealistic” and “unfeasible,” said Kamerhe.

And Tongba said the calendar wasn’t reached by consensus, and that it disenfranchises about 10 million youths, because the process makes no provision for registering those who reached voting age since the registration drive preceding the last election.

“Since Kabila is primarily concerned with prolonging [his term], if no political option is presented then the entire process will go off track,” said Tongba.

Kamerhe said the opposition has proposed a more realistic calendar.

He acknowledged that there are questions about whether the opposition offers a credible alternative to Kabila.

Kamerhe, noting his country’s abundant freshwater, hydroelectric, and mineral resources, said the DRC could play an important role in climate change and food security issues, but that “we are a very poor nation because of a lack of visionary leadership.”

Kamerhe also emphasized the need for rule of law and protection of human rights, especially in eastern DRC where the Ugandan rebel group Allied Democratic Force and the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR) have been waging a war.

In February, the Kinshasha government launched an offensive against the FDLR, which includes militiamen and former Hutu soldiers linked to the 1994 genocide in Rwanda.

Kamerhe said the DRC should build ties with its neighbors—especially Rwanda, Burundi, and Uganda—through deeper economic cooperation. He noted that while China can and does invest in the DRC, nearby African countries cannot.

“We need to have a level playing field,” Kamerhe said.

However, stability and security will be key to deepening economic ties.

At least forty-two people were killed in anti-Kabila protests in January, according to international human rights groups. Badibanga warned that similar violence could erupt again if young voters feel disenfranchised by Kabila’s latest attempts to cling to power

“If the situation is unresolved, their reaction is unpredictable and we may not be able to control” them, he added.

Ashish Kumar Sen is a staff writer at the Atlantic Council.

Image: US Secretary of State John F. Kerry urged President Joseph Kabila in a meeting in Kinshasa on May 4, 2014, to respect the constitution of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and not run for a third term in office. (REUTERS/Saul Loeb)