What the new British ambassador to the US means for the ‘special relationship’

Every British ambassador to the United States since the late 1970s has been a career diplomat rather than a political appointee, until now. In late December, well-known Labour politician Peter Mandelson—Lord Mandelson—was named as the British government’s choice to represent its interests in Washington.

The former member of Parliament, cabinet minister, and European Union (EU) trade commissioner is one of the most consequential British politicians of the past four decades. While his political appointment makes him an unorthodox pick, he nonetheless brings a wealth of experience and expertise that Prime Minister Keir Starmer believes will give London significant heft in the Trump White House.

“He’s a big, serious figure for big, serious work,” a Starmer aide said to me recently. “Team Trump can have confidence that this is a serious operator with the confidence and ear of the prime minister.”

Starmer is not the first British political leader to have turned to the mercurial talents of Mandelson. He was instrumental in turning around the electoral fortunes of an anachronistic Labour Party under Neil Kinnock in the late 1980s before becoming a key lieutenant to Tony Blair, who swept to power in 1997, and his successor in Downing Street, Gordon Brown.

Equally revered and feared, he was labeled by some as the “Prince of Darkness” for his political cunning and ruthless communications expertise—skills that will serve him well in Washington, DC, at a time when the “special relationship” between the United Kingdom and the United States looks likely to be severely tested.

Key tenets of this long-standing alliance, including a shared commitment to free trade, multilateral institutions, and European security, are expected to be challenged by President-elect Donald Trump’s policy agenda. “Our man in Washington,” takes over from the widely respected Ambassador Karen Pierce early this year, is going to have his work cut out for him.

The United States is the United Kingdom’s largest national trading partner, and total trade between the two countries is worth almost three-hundred billion dollars per year. So, a key part of Mandelson’s brief will be to seek to protect British goods and services from Trump’s threatened import tariffs.

He will also want to explore the possibility of reviving work on a free trade agreement between the two countries that stalled with US President Joe Biden’s election to the White House in 2020. While Trump offers fresh hope for such a deal—made possible by the United Kingdom’s departure from the EU—significant obstacles remain, not least on opening up agricultural markets on both sides of the Atlantic.

The prize of success would, however, be significant for the United Kingdom because of its need to boost the performance of its sluggish economy which, according to the latest government figures, saw zero growth between July and September 2024.

Having served as the EU’s trade commissioner between 2004 and 2008, Mandelson will bring considerable expertise in this area. Yet his task will not be made any easier because of the British government’s desire to build closer economic and political ties with the EU at the same time.

There is skepticism that the United Kingdom can secure greater trade alignment with both the EU and the United States, with some describing it as a “trying to have his cake and eat it” approach. Moreover, some in the Trump camp, traditionally hostile to the EU, are warning that the Brits must choose one or the other.

Starmer, however, is determined to challenge the idea that he has to pick a side and used a keynote speech in London in early December to say:

“Against the backdrop of these dangerous times, the idea that we must choose between our allies, that somehow we’re with either America or Europe, is plain wrong. I reject it utterly. [Clement] Attlee did not choose between allies. [Winston] Churchill did not choose. The national interest demands that we work with both.”

Protecting the long-standing security relationship between the United States and United Kingdom will continue to be a top priority. An immediate challenge for Mandelson will be to help secure British influence over the new administration’s Ukraine policy. The British government will want to see that Trump’s promise to end the war is carried out in such a way that it enhances Kyiv’s sovereignty and interests, as well as acts to deter future Russian aggression in Europe.

In a broader context, the United Kingdom will look to ensure that the United States under the new president continues to be committed to Europe’s defense through NATO. This will be no easy task at a time when some prominent voices in the incoming Trump administration are seeking to shift military and diplomatic resources away from the continent to focus more on China’s threat in the Indo-Pacific.

Mandelson will also arrive in Washington at a time when billionaire businessman Elon Musk, now a close adviser to Trump, has been using his X social media platform to post highly critical remarks against the British Prime Minister and his government. Musk has called for new elections in the United Kingdom and has reportedly offered to provide millions of pounds to support the populist, far-right Reform UK party led by Nigel Farage.

With a considerable parliamentary majority, there is no chance of national elections in the United Kingdom any time soon. But many will wonder how Mandelson, a center-left, pro-Europe free trader, will be able to win over Trump and right-wing Republicans in the administration. Yet he shares the president-elect’s acute understanding of power and how to deploy it. Moreover, Mandelson’s direct line to Starmer, personal charm, and policy expertise will prove invaluable in his dealings with the new administration in the White House.

Like Trump, Mandelson also recognizes the importance of political theater and is no stranger to controversy. He resigned from Blair’s government twice—once for failing to declare a home loan from a cabinet colleague, and a second time over accusations (later dismissed) of using his position to influence a passport application.

As a regular commentator in the British media, Mandelson has made some critical remarks about Trump in recent years, and his nomination as the British ambassador to the United States has already been met with a disapproving and undiplomatic social media post from Chris LaCivita, Trump’s 2024 campaign co-manager.

Appointing Mandelson carries risk, not least because he is a politician that will always divide opinion and generate noise. But he brings skills and weight to the job that very few others offer at a time of unprecedented challenges. It’s a bold statement of intent from a British government that believes it must build a constructive relationship with the new US administration. Time will tell if it is right.

Ed Owen is a nonresident fellow of the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center and a former UK government adviser.

Further reading

Wed, Nov 6, 2024

Donald Trump just won the presidency. Our experts answer the big questions about what that means for America’s role in the world.

New Atlanticist By

When Trump returns to the presidency on January 20 next year, a number of global challenges will be awaiting him. Our experts outline what to expect.

Wed, Oct 2, 2024

A man in a hurry: Keir Starmer’s early approach is making waves at home and abroad

New Atlanticist By

The new UK prime minister’s much-anticipated speech at the Labour Party’s recent gathering in Liverpool is a window into where the country may be headed.

Thu, Jul 11, 2024

UK foreign secretary: Why NATO remains core to British security

New Atlanticist By

With a return of war to Europe and security threats rising, strengthening Britain’s relationships with its closest allies is firmly in the national interest, writes UK Foreign Secretary David Lammy.

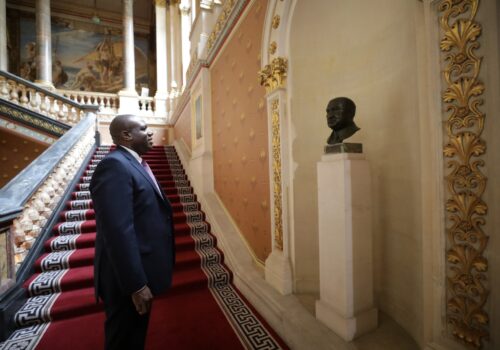

Image: PA via Reuters London, UK. 10 October 2023. Peter Mandelson speask to presenters from GB News during the Labour Party Conference in Liverpool. Matt Crossick/Empics