As US President Joe Biden arrives in New York this week for the United Nations (UN) General Assembly, he has his eyes cast across the Atlantic to legacy-making initiatives to strengthen relations with Africa. His UN ambassador, Linda Thomas-Greenfield, recently announced that the United States is supporting the creation of two permanent seats for Africa on the UN Security Council. The White House also tipped off reporters to Biden’s upcoming visit to Angola, fulfilling a promise by making his first trip to Africa—and drawing an implicit contrast with his predecessor, who never set foot on the continent during his time in office.

Taken together, these are landmark events in US-Africa relations and will help address the United States’ longstanding shortcomings in engaging the continent as its geopolitical rivals gain traction there. But there are significant challenges to fully developing these diplomatic efforts, which will only bear fruit if executed effectively.

Inside the Security Council

The Security Council was first established in 1945 with eleven members and now boasts fifteen—five permanent members (the United States, France, the United Kingdom, Russia, and China) and ten members who rotate in on two-year terms, by vote of the General Assembly. The five permanent members each can veto actions by the Security Council, which can include sending UN peacekeepers to conflict zones.

Unfortunately, the US announcement of support for new African permanent members was accompanied by an important limitation: They would not have the all-important veto power. While the United States is not willing to propose a systemic reform that would upend the post-World War II geopolitical order by granting additional countries veto power, it is nevertheless the first among the permanent five members of the Security Council to explicitly support permanent membership for African countries. As for the Africans, they recently confirmed the importance of extending the veto power to all the new members or to remove it for all.

Interestingly, Africa played an important role in perhaps the most significant change to the Security Council: the 1971 change in the permanent member seat from the Republic of China (aka Taiwan) to the People’s Republic of China. At the time, Mao Zedong spoke of a debt of gratitude to African nations and other developing countries that “carried” his country’s bid.

An increased presence for Africa on the Security Council makes sense given the demographic rise of southern nations, many of which gained their independence in the mid- to late twentieth century, bringing the number of UN member states from 51 in 1945 to 193 today. Nowhere is that rise more pronounced than in Africa. One in four human beings will be African by 2050, and by the end of the century, it is predicted that Africa will be the most populous continent on the planet. Within the General Assembly, African nations hold 28 percent of the votes, ahead of Asia (27 percent), the Americas (17 percent), and Western Europe (15 percent).

In addition, the large number of conflicts on the continent, from Sudan to the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), certainly calls for greater participation by Africans in their resolution.

Calls to increase Africa’s representation on the Security Council seem to be gaining traction more widely among UN member states. On September 22, the UN adopted the Pact for the Future, which, among other stated priorities for reform, calls for plans to “improve the effectiveness and representativeness of the [Security] Council, including by redressing the historical under-representation of Africa as a priority.”

But adding African nations to the Security Council as permanent members is far from a done deal. In order to enter into force, such a reform would require a revision of the UN Charter by agreement of two-thirds of the General Assembly, including the five Security Council states with veto power.

Moreover, it is unclear how Washington’s commitment is compatible with its previously expressed willingness to also support the permanent membership of India, Germany, Japan, and a country from Latin America and the Caribbean on the Security Council. Will the United States really advocate for adding six more permanent members?

Africa, a field of rivalry with China

In the push for permanent African Security Council seats and the news of Biden’s upcoming trip to Angola, many observers see a willingness by the United States to respond to the West’s setbacks in Africa amid a diplomatic and strategic offensive by China and Russia. An April 2024 Gallup poll confirmed that Russia is seeing an increase in popularity (up 8 percent year-on-year) on the continent. Also, China (58 percent approval) is now more popular than the United States (56 percent) across Africa.

China has been the leading trading partner of African countries since 2009. In 2023, their trade amounted to $282 billion, a thirty-fold increase in twenty years. Over this period, Chinese companies built a third of the continent’s infrastructure projects, from power plants and hospitals to presidential palaces and even the headquarters of the African Union in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia—which, it turned out, China had reportedly wiretapped.

While these projects have come at a cost of high levels of indebtedness in Zambia, Kenya, Ethiopia, and elsewhere, they have also enabled African countries to cover some of the gaps between their infrastructure needs and available financing. Egypt and Ethiopia, along with Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates, have also joined the BRICS grouping of emerging economies (previously Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa). The BRICS+6 now constitutes 46 percent of the world’s population and nearly 36 percent of the world’s gross domestic product.

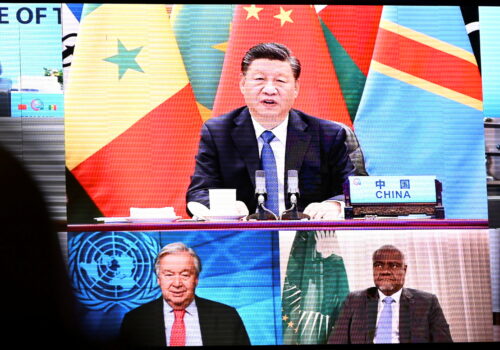

For Washington, all this meant that declarations of love for Africa were no longer enough: It had to show proof. The Biden administration responded by resuming US-Africa summits, such as the remarkable one in December 2022 in Washington and by mobilizing fifty-five billion dollars in investments across the continent over three years. It also launched new projects (such as the Lobito Corridor for critical minerals), unveiled a digital transformation plan, and pushed for the creation of a permanent seat at the Group of Twenty (G20) for the African Union. And yet, China has continued to make diplomatic inroads: China-Africa forums attract many African leaders, and even UN Secretary-General António Guterres attended one such meeting in Beijing this month.

The United States is making a bold strike by announcing its support for two permanent Security Council seats for Africa, a step the African Union has formally called for since 2005. Neither Russia nor China, despite all their posturing as the best advocates for Africans, has gone so far. For years, these two countries, as permanent members of the Security Council, had championed the misnamed “Global South” without putting anything concrete on the table or ceding their own prerogatives within the most powerful body of the UN system.

Who will sit on the Security Council?

On the African side, this new reform proposal has immediately triggered a cascade of questions: Which two African states would join? How would they be chosen?

Should priority go to African countries with high economic growth? In this case, South Africa ($373 billion) and Egypt ($347 billion), are the continent’s two largest economies according to the International Monetary Fund’s World Economic Outlook released in April. But for how long? Just two years ago, Nigeria was the continent’s largest economy.

But what if demographics are the determining factor? Nigeria remains the continent’s leading demographic power, with 225 million inhabitants, according to the UN Population Division, and Ethiopia (127 million) should be recognized as highly populous, too.

South Africa, the country of Nelson Mandela, has a case that goes beyond economics and demography. Its national liberation, in which most African countries have participated, resonates the world over, though xenophobic violence against some African migrants there has been a problem of late. After its first democratic elections in 1994, one of Africa’s most multiracial countries adopted one of the world’s most democratic constitutions. Until this year, South Africa was the only African member of BRICS; it remains the only African country in the G20, which it will take over the rotating presidency of in December. In 2010, South Africa became the first African nation to host the World Cup, using its sports diplomacy to boost its soft power. But will post-Mandela South Africa finally agree to look at Africa instead of the Indian Ocean? When will we see a pan-African strategy for the rainbow nation?

Finally, there is the DRC, a counterintuitive choice among the African contenders for the Security Council. Bordering nine countries, this huge nation is rich in cobalt, copper, zinc, gold, and platinum, which are essential to the global energy transition. The DRC is also rich in culture, boasting two hundred languages. Kinshasa, home to seventeen million people, is the world’s largest French-speaking city—ahead of Paris.

But perhaps most important to the DRC’s case is the fact that it has direct, and devastating, experience with the conflicts the Security Council tries to manage from afar. It has seen thirty years of civil wars, coups, and the impotence of the UN’s oldest peacekeeping mission, as it now grapples with the challenges posed by hosting more than 6.5 million internally displaced people. The Congo’s plight is a long tragedy that no longer seems to interest the international community. That is why the country needs a powerful lever, such as this seat on the Council would provide. It should come on one condition, however: that its political leaders live up to the challenge.

Rama Yade is the senior director of the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center.

Further reading

Thu, Sep 19, 2024

The Sudan crisis has become a magnet for foreign malign influence and strategic corruption

New Atlanticist By

To help bring about an end to the war in Sudan, the United States should stem the illicit activities of foreign actors fueling the conflict.

Wed, Sep 18, 2024

The Sahel is now an epicenter of drug smuggling. That is terrible news for everyone.

AfricaSource By Alexander Tripp

The international community may be overlooking an emerging threat in the Sahel—one that will have colossal impacts for geopolitics in the region and beyond.

Thu, Aug 29, 2024

Xi wants to enlist the Global South in his anti-American movement

New Atlanticist By Michael Schuman

The Chinese leader’s approach to the developing world has become consumed by Beijing’s geopolitical competition with the United States and its allies and partners.

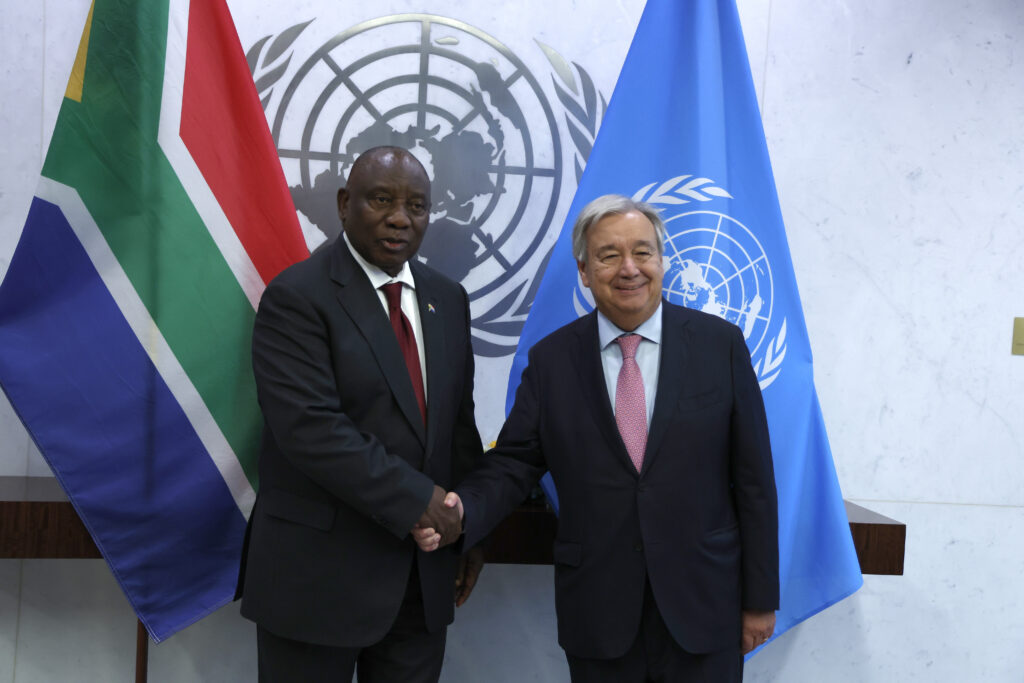

Image: UN Secretary-General António Guterres meets with South African President Cyril Ramaphosa at the United Nations Headquarters on September 22, 2024, in New York City. Photo by John Lamparski/NurPhoto.