Michelle Bachelet, the outgoing United Nations (UN) human-rights chief, should have known better.

In a previous life, the Chilean physician-turned-politician was the victim of a brutal regime, detained along with her family and tortured at the age of twenty by dictator Augusto Pinochet’s security services in response to her father’s political activity. While her father died in prison, she survived and eventually went on to serve as Chile’s first female president and UN high commissioner for human rights.

But as her commission ends in August—Bachelet announced this week that she will not seek another term—her human-rights legacy falls woefully short.

Given her background, I had high hopes for Bachelet’s visit last month to China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region—the first by a UN human-rights chief to the country in seventeen years. There, she had the opportunity to challenge Beijing’s oppression of ethnic Uyghurs like my brother Ekpar Asat. As a lawyer, I was not naive about the brokenness of the UN system; still, I saw her as the hero we’d all hoped for, speaking truth to a powerful China and drawing attention to its crimes.

Instead, Bachelet played along with China’s carefully sanitized charade.

Her trip was meant to be a fact-finding mission to build upon the existing evidence of the widespread mistreatment of Uyghurs. It also coincided with the massive leak of documents and photos revealing what Uyghurs endure in China’s brutal camps and the systemic nature of the terror. But Bachelet didn’t seem interested in any deep probing, reportedly telling diplomats ahead of her trip not to get their hopes up.

In recent months, China has removed all visible signs of its atrocities from the regional capital of Urumqi, including its Orwellian checkpoints, surveillance cameras, and barbed wire. During Bachelet’s visit, local residents like my own family were restricted from going out. While there, she effectively echoed the government line by referring to Beijing’s collective punishment against Uyghurs as “counterterrorism responses.” In doing so, I believe she dehumanized the peace-loving Uyghur people. I am also concerned that China would view her stance as a tacit endorsement to further repress the Uyghur people.

Probably eager to exploit her visit, state media reported that Bachelet “congratulated China on its important achievements in economic and social development and in promoting the protection of human rights.” Bachelet did, indeed, praise China’s poverty alleviation effort, which has provided some citizens better economic opportunities. But the Uyghurs are not among them—and in fact, Beijing uses “poverty alleviation” as a slogan to exploit Uyghurs by transferring them to forced-labor factories. Her statement simply revealed what seems to be a lack of understanding of how China would seize on such commentary to paint an entirely different picture.

I feel defeated. Unlike the high commissioner, I can no longer visit China after narrowly escaping the concentration camps where my brother remains imprisoned. I needed her to defend his dignity. I wanted—and expected—her to speak directly to victims like him in order to send a defiant message to China: Uyghur lives matter. Instead, Bachelet spoke to Guangzhou University students, delivering conciliatory remarks about cooperation with China instead of condemning the genocide. This week in Geneva, she admitted that her trip faced “limitations” and that she was unable to speak with any detained Uyghurs or their families.

Perhaps it’s not apparent to her, but my beloved parents and community have been torn apart, bearing the scars of loss and the horrors inflicted by the Chinese government over the past six years. Future generations of Uyghurs will carry this painful legacy. Their worldview will be shaped by genocide.

I still cannot process a simple fact: How could a torture survivor fail to openly support other survivors and go so easy on their oppressor? After all, Bachelet has a history of fighting for democracy and the marginalized: While her presidency was not perfect, she reformed the Chilean military, improved access to health care for low-income families, and promoted literacy. She also opened the Museum of Memory and Human Rights to document the abuses of the Pinochet regime—pushing Chile to become one of the few countries in the world that has truly dared to confront its past.

In her current role, she strongly condemned other atrocities and wars, such as Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, the genocide against the Rohingya community, and the Taliban’s treatment of girls. But the Uyghurs are still waiting for her report. I hope that during her final two months in the office my brother and other victims can count on her.

I even saw my own story in Bachelet’s: My brother’s ordeal drove me to become a principled advocate for human rights. But now I keep wondering how she could possibly ask me to convey her message of managed expectations to victims like my brother, whose cries through prison walls haunt me every day. Whatever her motivation, Bachelet has betrayed both the Uyghurs and her mandate as the UN human-rights chief.

Can the power of the office change a person that much? And what is the purpose of that office if one cannot expect its occupant to stand up against one of the most egregious human-rights abuses of this century? I wonder how the young, idealistic Chilean girl—who was fortunate enough to be freed from her own detention—would answer these questions. Where has that girl gone?

Rayhan Asat is a nonresident senior fellow with the Strategic Litigation project at the Atlantic Council and a Tom and Andi Bernstein Human Rights Fellow at Yale Law School.

Further reading

Wed, Feb 16, 2022

Financing & genocide: Development finance and the crisis in the Uyghur Region

Report By

A joint report that reveals how the World Bank’s International Finance Corporation (IFC) has significant investments in China’s Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, where indigenous peoples have been subjected to what international legislators, legal scholars, and advocates have determined to be a genocide.

Tue, Dec 21, 2021

The US can lead the way to ending China’s modern slavery. My brother is counting on it.

New Atlanticist By Rayhan Asat

Moral arguments have been unable to sway global firms—so it’s time for the full force of the US government to step in.

Wed, Feb 23, 2022

China and Russia are proposing a new authoritarian playbook. MENA leaders are watching closely.

MENASource By Ahmed Aboudouh

It’s on major Western democracies to make democracy appealing again by aggressively filling the gaps China and Russia exploit to make the world more accommodating to their political models and the new trend of rising authoritarianism.

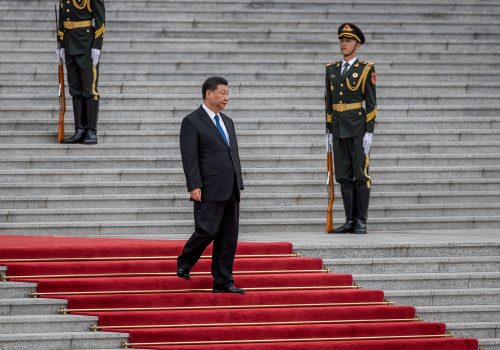

Image: UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet attends the Human Rights Council at the United Nations in Geneva, Switzerland, on June 13, 2022. Photo by Denis Balibouse/REUTERS