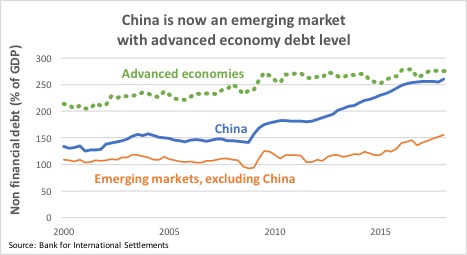

China has incurred the largest debt buildup in recorded economic history—and the prognosis is not good. The International Monetary Fund surveyed five-year credit booms near the size of China’s and found that essentially all such cases ended in major growth slowdowns and half also collapsed into financial crises.

A 50 percent chance of a financial crisis for the world’s second-largest economy would represent one of the greatest threats to the global economy.

Can China avoid a crisis? Both bears and bulls make equally compelling arguments about China’s current challenges, suggesting the probability of a major crisis is in line with the historic precedent of 50/50.

Bears warn that Beijing is juggling too many challenges at once while growth drops, making a crisis more likely.

Beijing risks making a misstep as it attempts to manage seven economic policy challenges at once:

1. Slow deleveraging: While credit growth has moderated to come in line with economic growth, debt-to-gross domestic product (GDP) ratios remain high and steady.

2. Persistent financial risk: Financial regulatory overhaul continues, but new shadowy corners pop up as soon as old ones get regulated, while property prices remain elevated.

3. Monetary/external imbalance: The strategy of using monetary liquidity to support the financial system amid regulatory tightening is running headlong into Federal Reserve tightening, weakening the renminbi and retesting capital controls.

4. Geopolitics: Even before the Trump presidency, China and the United States were poised to become competitors as China climbs the value chain and offers an alternative model. For a country as large as China, the middle-income trap is harder because it also leads to a Thucydides Trap (the pattern of established powers fearing rising powers, historically leading to conflict three-quarters of the time and likely to strain China’s integration with Western economies).

5. Social contract: Convincing people to accept lower growth and higher default risk will be difficult.

6. Attracting foreign investors: Convincing international investors to use the renminbi and invest in China requires a credible commitment to avoid capital controls.

7. Sectoral restructuring: It will take decades to rebalance the economy toward domestic consumption, services, and advanced manufacturing, reform state-owned enterprises, and deepen capital markets.

China faces this array of challenges while its sustainable growth rate is falling by half, from a 10 percent average over four decades to a new normal around the 5 percent middle-income average.

The gravitational pull toward 5 percent growth is visible within last year’s GDP details. While 2017 headline growth surprisingly ticked up to 6.9 percent despite deleveraging, the IMF calculates that cyclical uplift of foreign demand and producer price inflation provided a temporary boost of two percentage points, without which real GDP growth would have been 4.9 percent.

Beijing faces a daunting array of growth, financial, geopolitical, and other challenges, making its idiosyncratic risk factors quite high.

Bulls hope China can sustain high debt levels without a major crisis.

Emerging markets are traditionally assumed to hit crises at lower debt-to-GDP levels than advanced economies. Reexamining this assumption reveals two stabilizing forces in China: state control and domestic savings.

First, the theory of debt intolerance argues that emerging markets default at lower debt levels due to unreliable track records of debt repayment and economic management. However, Beijing has strong administrative control over economic actors, backed up by a long history of steady development. Its record is imperfect and small to moderate crises do occur, but China’s debt capacity does not suffer from a poor reputation for economic management like other emerging markets.

Second, the same economists who introduced the concept of debt intolerance with respect to external debts later argued that the anomaly disappears when incorporating emerging markets’ large domestic debt burdens, held by residents and denominated in their own currency. Indeed, most of China’s debts are domestic, with high savings offering a resource to address financial problems, while alleviating the risk of fickle foreign investors rushing to exit. Domestic defaults are rising, but a destabilizing default wave is not inevitable simply because China is an emerging market.

Indeed, Beijing’s focus on stability has been demonstrated since the equity and currency shocks of 2015 motivated Chinese President Xi Jinping to prioritize deleveraging. De-risking started in 2017 by slowing interbank credit growth. The focus was initially on enforcing existing rules and holding firms and executives accountable, then setting out a multiyear plan to bring shadow banking into the regulatory purview. Beijing is also preparing to deleverage the real economy by updating the bankruptcy regime, deepening capital markets, bringing in foreign investors, and focusing on debts by state-owned enterprises and local governments. These efforts are more impressive than anything Western governments have done to contain past credit manias.

However, there are unproven hopes implicit within this bull case. One is that the technocratic command of Beijing will bring sufficient firepower to distribute losses in an orderly fashion, hiving out bad debts to new actors such as bond investors who are willing to pay to get into China. A second hope is that de-risking will persist through unfavorable environments. It will take a downturn to prove that financial risks are resolved and unsustainable stimulus habits are abandoned.

A reasonable bull case is that China remains stuck in the Japanese trap of policy consolidation working only in good times, with tightening defeating itself as it begets bad times, at which point policy backslides into ever-rising fiscal and structural problems that weigh on growth but avoid major crises. China has stronger controls than Japan, but also more geopolitical challenges, so the bull case may also require Xi to either wait out US President Donald J. Trump or rally the international community against Washington.

As China goes, so goes the global economy

In calculating contagion risks, the IMF finds limited global reliance on Chinese final demand and capital markets, meaning the sharpest spillovers would be regionally concentrated. Kenneth Rogoff, the International Monetary Fund’s former chief economist, calls this “wishful thinking,” warning that investors are already jittery about profit growth, much of which relies on future business in China, even if the capital market linkages remain underdeveloped. Rogoff also cautions that unlike US recessions, a Chinese downturn could coincide with rising US interest rates. Rogoff concludes by warning that China’s inevitable growth recession “will almost surely be amplified by a financial crisis, given the economy’s massive leverage,” and that this “would constitute the third leg of the debt supercycle that began in the United States in 2008 and moved to Europe in 2010.”

Whether or not China suffers a crisis, the global economy will enjoy less support from the twin engines of credit-fueled Chinese growth and aggressive monetary easing that powered the last recovery. If not for China, the global recession would have cut 50 percent deeper and the series of shocks throughout the recovery (euro crisis, taper tantrum, oil price decline, etc.) may have tipped the world back into recession. By contrast, high debts and low yields may well bring a major test of global economic and political stability with the next global downturn, whether or not it is triggered by China.

Josh Rudolph formerly served at the International Monetary Fund, the National Security Council, the US Treasury, and J.P. Morgan. Follow him on Twitter @JoshRudes.

Image: Chinese 100 yuan banknotes are seen in a counting machine in a bank in Beijing, China. (Reuters/Kim Kyung-Hoon/File Photo)