As a result of Syria’s five-year-long civil war, the country has suffered great humanitarian and economic losses. The war has set the country back decades in terms of economic, social, and human development. Here, some of these losses will be summarized, using a working IMF report: “Syria’s Conflict Economy.”

As a result of Syria’s five-year-long civil war, the country has suffered great humanitarian and economic losses. The war has set the country back decades in terms of economic, social, and human development. Here, some of these losses will be summarized, using a working IMF report: “Syria’s Conflict Economy.”

Before the Conflict

In the early 2000s, Syria was attempting gradual economic liberalization by taking several concrete steps: strengthening banking supervision and regulation, modernizing the monetary framework, developing a government debt market, strengthening and streamlining revenue administration, and improving public financial management, all with IMF technical assistance. The economy was stable.

However, there were indicators of underlying problems. Poverty and unemployment were beginning to rise during the latter half of the 2000s, and the disparity between rural and urban poverty was large. The economic liberalization efforts did not benefit rural populations, and Syria’s “Doing Business Indicators” were lacking: Syria performed poorly on access to finance, contract enforcement and registering property, in addition to problems with corruption, an inadequately educated workforce, and electricity. Political reforms were also slow, and frictions began to arise after Bashar al-Assad’s presidency began in 2000.

A Humanitarian Disaster

The Syrian conflict is considered the “worst humanitarian crisis of our time.” The Syrian population has shrunk by an estimated 20% with 250,000 people dead and another 800,000 injured, according to official UN figures. 4.7 million refugees have fled Syria, and there are another 7.6 million internally displaced Syrians.

Unemployment and poverty is widespread: 60% of the labor force is unemployed, three million people having lost their jobs from the conflict, poverty is estimated to be at 83% of the population, and 2.1 million homes have been destroyed.

Children are one of the most heavily affected groups in the conflict. About two million Syrian children are not in school, and one-quarter of schools in Syria are no longer operational as a result of the war. There have been 3.7 million Syrian children who were born as refugees since the start of the conflict.

Life expectancy has declined by 20 years due to the conflict. Vaccination rates for children have fallen to 50-70% from 99-100% before the crisis. There is little food security, and there is a struggle for consistent access to water and electricity.

Relief organizations lack the funds to support the 13.5 million people in need of aid and face challenges because of international sanctions targeting Syrian government officials and terrorist organizations. 4.6 million people are in hard to access areas, and the Syrian government has refused to authorize NGOs to distribute aid in some areas.

A Destroyed Economy

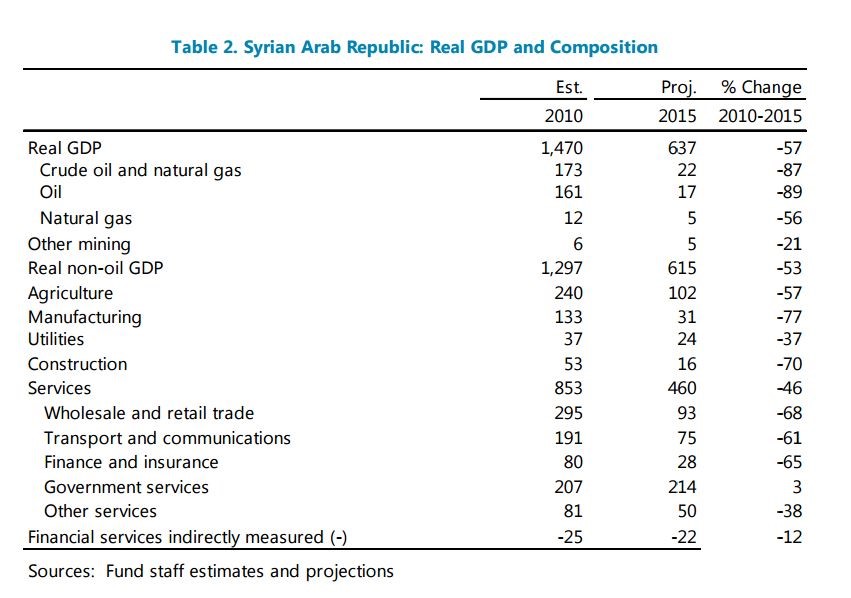

The economy has contracted in real terms by 57 percent since 2010. Output losses and physical infrastructure destruction are concentrated in the oil, manufacturing, transportation, and construction sectors:

Crude oil production in areas under government control has fallen to 9,000 barrels per day (b/p) in 2014 from 386,000 b/p in 2010—a 98% decline in oil GDP. However, total crude oil production is higher when accounting for output fields under rebel control that are sold on the black market.

Agricultural production once accounted for one-fifth of Syria’s economy before the conflict and has since experienced significant losses. Some of the more fertile areas—such as the Aleppo and Raqqa governorates, which accounted for half of Syria’s agricultural production—are largely out of government control. Wheat production is 20% lower than in 2010; livestock production has declined by 30% in cattle, 40% in sheep and goats, and 50% in poultry. Livestock accounted for 20% of the rural labor force, and sheep, goats, and chicken were important export commodities.

Manufacturing has been heavily affected by lack of input materials, limited access to trade finance, and infrastructure destruction. Many of the manufacturing centers of Syria were located in Aleppo, Homs, and the suburbs of Damascus—some of the most heavily affected areas of the war. A lot of Syrian business has relocated to Turkey, accounting for 26% of new businesses registered in Turkey.

In the external sector, the conflict and international trade embargos led to a 2015 current account deficit of 13% of GDP, up from 0.6% of GDP in 2010. Most of this deterioration is coming from the collapse in oil exports and tourism. Exports decreased by 70% between 2010-15 due to the international embargo, and imports declined by almost 40%.

The IMF speculates that there has been major capital flight while capital inflows have been limited, implying that (1) Syria has received little to no private financial and capital flows, including no investment; (2) Syria is no longer servicing its debt; and (3) it is no longer allowed any repatriation of any profits. The only assumed financial assistance is credit lines from the Iranian government.

Lastly, international reserves have been estimated to have dropped to $1 billion at the end of 2015, and the exchange rate has sharply depreciated as well, having lost an estimated 85% of its value against the dollar.

A Scattered Fiscal System

The fiscal deficit is estimated to have risen to over 20% of GDP in 2015, up from 8% of GDP in 2010. While Iranian credit finances some of the Syrian debt, the rest is covered domestically by the Central Bank and commercial banks. Public debt was above 100% of GDP by the end 2015, up from 31% of GDP at the end of 2009.

Foreign currency and raw material shortages have forced government forces to cut back on wheat, bread, sugar, fuel, water, and electricity subsidies. The Syrian government has also been forced to outsource a majority of necessary services to the private sector and has reached agreements with the Islamic State (ISIS) and the Kurds to buy Syrian crude oil and gas to ensure supplies for areas under regime control.

The financial sector is in disarray. Syrian banks are largely isolated from the international market—three-quarters of the banking market largely shut off from international payment and settlement systems as a result of the international sanctions—and a majority of international assets have been frozen. Non-performing loans are a large problem, as well, having increased to 35% by September 2013, up from only 4% in 2010.

How to Rebuild?

Rebuilding physical infrastructure will cost an estimated $100 to $200 billion, and Syria will have to overcome vast socioeconomic challenges. Using recovery times in Lebanon and Kuwait after their respective conflicts as a reference, it can be roughly estimated that if Syria stabilizes in 2018, it could take 20 years for its economy to return to pre-conflict GDP levels. However, considering the unprecedented level of devastation, it could take longer.

In the short run, Syria must aim its economic reforms toward stabilization and helping the poorest. After security has been restored and reconstruction is underway, more far-reaching reforms should be considered, such as developing non-oil sectors and maintaining fiscal sustainability while providing social protection to unemployed youth. Private sector development is critical. There is also environmental and natural resource challenges, particularly relevant to the stress that has been put on the water supply and sanitation sectors.

In sum, Syria must consider how it will deal with its regional disparities when it begins to rebuild to avoid repetitive instability. It is necessary for fiscal policy and management to be effective, fair, and transparent, and once economic reforms commence, there must be an awareness of the treacherous socioeconomic conditions that started the conflict in the first place.

Brandi Young is an intern at the Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East.

Image: PHOTO: A money exchange vendor holds Syrian currency notes inside his shop in a rebel-controlled area of Aleppo, Syria, May 11 2016. REUTERS/Abdalrhman Ismail