Key takeaways

- Supporting civil society organizations and their constituencies is crucial to initiating a public discussion about the security sector

- Syrian survey respondents are reluctant to allow oversight managed outside civil society organizations or the parliament

- Syrians want a police force to provide security for citizens and not offering sole special protection to a political leader

The structure and characteristics of the pre-conflict Syrian security sector contributed heavily to the outbreak of the Syrian civil war; for decades, it stood for corruption, discrimination, violent repression, and large-scale human rights abuses. When the Arab Spring began to unfold in Egypt and Tunisia in early 2011, a group of Syrian school boys got detained for writing anti-regime graffiti on a wall in the city of Daraa. For weeks, the boys were heavily tortured by security forces; a thirteen-year old died. Their families protested against the detention and treatment of their children, decrying the violent repression of the Syrian people. The Syrian government responded to the protests with an even more violent crackdown. Dozens died and every subsequent funeral turned into another protest that was dispersed by security forces. The situation eventually escalated into a fully-fledged civil war, involving a myriad of national and international actors.

As the security sector was one of the major causes of the war in Syria, its reform needs to be part of the solution. To better address such reform, we conducted a security needs assessment with Syrians in Germany with the aim of contributing to open-access information on security sector reform (SSR) in Syria between March and August 2018. The assessment was specifically designed to understand Syrian citizens’ needs and identify entry points for citizen-oriented SSR efforts. It analyses how the Syrian security system would need to change so that Syrians could feel safe and secure in a post-war Syria.

The questionnaire consisted of sixty-three questions focusing on insecurity and injustice in Syria before and during the war, the assessment of Syrian state security providers, and visions for an ideal security sector for post-war Syria. Of the 2,318 Syrians living in Germany that opened the questionnaire, 619 completed it. Of those that completed the questionnaire, 88 percent were men and 12 percent were women. Their ages ranged from seventeen to fifty, with an average age of twenty-nine.

Survey participants mostly held state security forces responsible for repression and violence and perceived family as the major source of protection

Despite a small set of participants, the results showed few felt safe and secure in Syria before the war. Survey participants mostly held state security forces responsible for repression and violence and perceived family as the major source of protection. So, reconstructing infrastructure and social systems without addressing a repressive security system that is strongly linked with a partial and unfair justice system is unlikely to achieve sustainable peace in post-war Syria. This is especially the case for issues related to the long-lasting war, such as addressing war crimes, compensating victims and integrating former combatants, including of militias and opposition forces, into the society.

The challenges of addressing security sector reform

Addressing SSR in Syria is problematic in many ways. First, Syrians are afraid of speaking about the topic and expressing their opinions. One survey participant, for example, explained that in Syria, “[i]t was not possible for any human being to express an opinion contrary to the opinion of the state without fearing for his/her life and the life of the family.” People regularly were ‘disappeared’ or imprisoned for speaking out. Syrians that left Syria took this fear with them.

It was challenging to find a target group to take the survey itself. Even Syrians in Germany are afraid of risking persecution for expressing their opinions and sharing information, mainly for relatives and friends in Syria. Some expressed the fear that the authors might have worked for Syrian security forces or German institutions responsible for refugees, such as the Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF) or the Foreigners’ Authorities of the German federal states (Ausländerbehörden); which could impact their legal status. In addition, access to women and girls was particularly challenging. Often, they told us that security was a “man’s topic” and should not concern them.

Second, the war in Syria is not over yet. The international community shows interest in SSR, but only made progress on processes dependent on a political solution. If and how the security sector will undergo reforms also depends on the will of the future government. When presenting survey results to national and international stakeholders, we were often told that security was a highly political topic and that a pure humanitarian engagement was the only possible way to support Syrians in Syria at the moment. We were told that, in fact, the security sector touches upon national security matters and who gets involved in their reform is a political decision.

Third, there is not much information available on the Syrian security sector and the actual needs of Syrian citizens. This lack of information makes it even easier to ignore security-related topics when addressing post-war reconstruction. However, it should not hinder thinking and discussions about post-war security in Syria and its importance for all other development sectors.

Given the importance of SSR, to a stable post-war Syria in which all citizens can be safe and secure, it is imperative that the challenges above be mitigated. This is why we asked the Syrian diaspora in Germany what would need to change in terms of security provision in post-war Syria and started a debate with relevant stakeholders about it.

Elements of a safe post-war environment

Through their answers to the questionnaire, it is evident that Syrians have clear expectations towards a post-war security sector in Syria. Most of them did not leave Syria for better job opportunities or better education, but to live in a safe country that respects human rights.

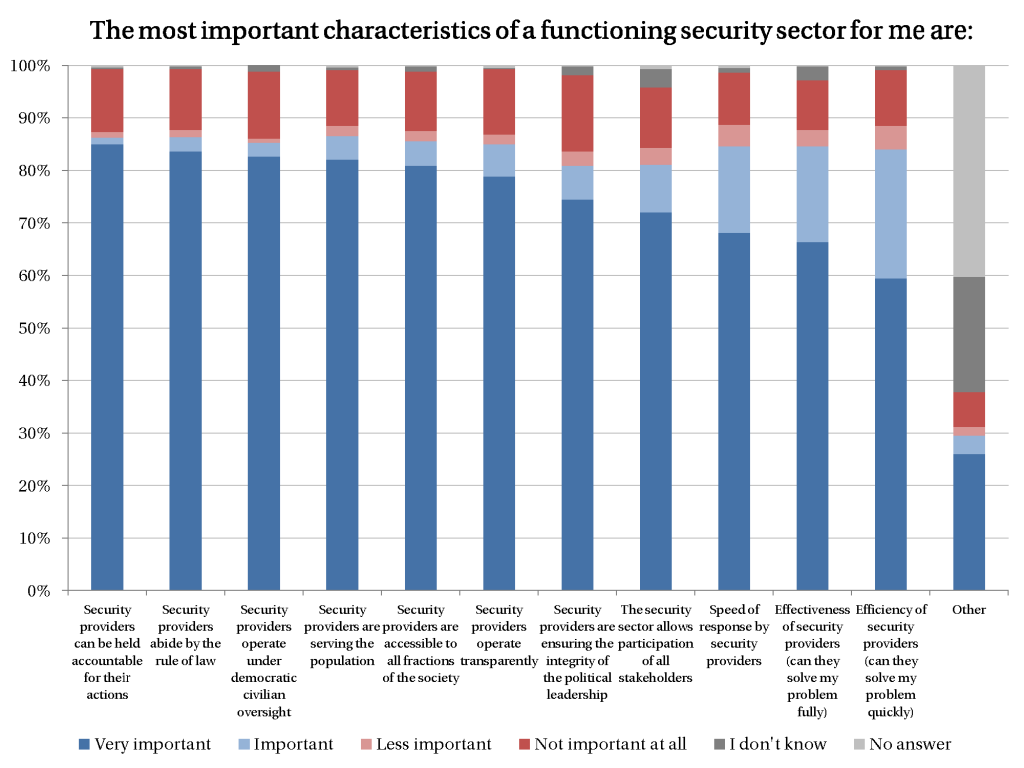

Survey participants defined a functioning security sector in terms of overarching principles (e.g. accountability and rule of law) setting the framework in which security providers could operate and not in terms of quality of service provision (e.g. effectiveness and efficiency of the security providers). They made very clear that a security sector that is only efficient and effective is less important for them than a security sector that can be held accountable for its actions, abides by the rule of law, and is placed under civilian oversight.

The purpose of a security sector was also crucial in this regard. Survey participants made clear that a security sector that serves citizens contributes to its ability to function. Furthermore, participation was a central element of a functioning security sector for survey participants. Nearly one-fifth of the survey participants rejected the idea of having security institutions that only serve the political leadership. This could mean that this group opposes the politization of security institutions. It could also mean that they reject an exclusive use of the security institutions for specific actors.

Question analysis

Of all the questions asked in the questionnaire, reactions to the statement “security officials who commit crimes against citizens should be brought to court” received the highest number of consent: 99 percent fully agreed and 1 percent somewhat agreed. The question was asked in a general manner, implying crimes of the past, the present, and the future. Before, and especially during the war, security institutions were responsible for grave and frequent human rights abuses. According to survey respondents, these crimes need to be addressed one day, embedded in a national reconciliation process.

In an ideal Syrian security sector, 91 percent of the survey participants would want the police to be the entity responsible for providing security for citizens. This means that nearly all survey participants supported the idea of a centralization of citizen-oriented security services provided by the police, although they also characterized the police as responsible for repression and violence before and during the war. The results show that survey participants wish to have a police force that actually responds to their needs. That survey participants reacted so positively to questions regarding a future Syrian police force is blessing and curse at the same time. On the one hand, Syrians might react optimistically regarding police reform. On the other hand, if reforms do not achieve positive results in a short period of time, citizens might get very disappointed and project this disappointment on the whole security sector and its reform.

When we asked if there should be specific security providers only serving the protection of the president, two-thirds of the survey participants responded negatively. It might be that participants would fear for the independence of the security sector if there was a specific force just serving the president, especially because such a force could also be used for political persecution of opponents. It could also be that survey participants refused the idea of offering special protection to a political leader while many of them live in insecurity themselves.

Decentralized decision-making

Survey participants opted for decentralized decision-making when it comes to the security of citizens. In a post-war Syria, 52 percent fully agreed and another 30 percent somewhat agreed to the statement that decisions governing the security of citizens should be taken in the governorates and not in the capital. The results reflect distrust in a centralized security approach decided by the government in Damascus. Participants agreeing to the statement think that local decisions better respond to their needs. When comparing the results from participants from Damascus with those from Aleppo as well as other governorates, participants from Damascus were less likely to agree to the statement.

The role of civil society and the parliament

Survey participants attributed a strong role to civil society and the parliament in charge of oversight: 76 percent chose civil society and while 73 percent chose the parliament. In comparison, the Ministry of Interior only reached 37 percent, making it the highest ranked government institution. The results show that survey participants are reluctant regarding oversight not managed by civil society or the parliament. This means that both parliament and civil society are needed in overseeing the security sector. It is necessary to assess whether they have sufficient capacities to exercise this oversight role or if they need further training.

Little hope for reconstruction and reconciliation without SSR

With hostilities in Syria nearing their end, reconstruction is becoming more relevant every day. The issue remains political and questions continue about the actors involved and what foreign efforts will entail. However, reconstruction cannot be overlooked for Syrians’ human security conditions to improve. A continuity of the pre-conflict security sector set-up will inevitably entrench the conditions that led to the outbreak of the conflict.

Recommendations:

In order to improve the human security conditions of Syrians and to stronger incorporate security considerations in overall reconstruction efforts for Syria, we recommend the following steps:

- Further analyze the security needs of the population – be it in Syria or in host countries, through quantitative surveying and focus group discussions, etc.,

- Support civil society organizations and their constituencies to initiate a public discussion about the future of the security sector in Syria, including its institutional set-up, goals, budget allocations, accountability mechanisms, complaint systems, etc.,

- Strengthen civil society groups and media outlets outside Syria to establish a platform for diaspora Syrians to debate and exchange on reform priorities for their country,

- Ensure that any SSR or disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) process is linked to reconciliation based on lessons learned from other conflicts where crimes were committed in conflicts with members of security forces,

- Support the Syrian civil society actors in the Syrian constitutional committee in adequately addressing all constitutional issues linked to the security needs of the civilian population,

- Prepare for SSR scenario planning, in case a political window of opportunity allows engaging in the reform of the Syrian security sector towards improved accountability, transparency, citizen-orientation, and a stronger foundation on international principles of the rule of law.

Nora-Elise Beck and Lars Döbert have worked on SSR in the Middle East. Together, they founded Lanosec, a consulting organization for SSR and good governance.

Related reads

Image: Syrian security tries to quash dissent in Douma, but residents remain defiant, Jan. 14, 2012. (Elizabeth Arrott/VOA)