The evolution of Syrian revolutionary art

When protests broke out in Syria in early 2011, the demonstrators demanded the end of the national emergency law—in place for over 40 years—, and other basic democratic reforms. Syrian President Bashar al-Assad paid lip service to all of these demands well before 2011 so, in light of protests sweeping the Arab World, demonstrators must have felt that such requests were not especially outlandish.

Then, in February 2011, a groups of boys scribbled anti-regime graffiti walls outside their school in Daraa. “It’s your turn doctor,” they spray painted, referring to Bashar al Assad, who was formerly an ophthalmologist. Graffiti certainly wasn’t rare, but the regime understood its possible implications to the point where ID was needed to buy spray cans if the government needed to find the buyers. The boys, who painted graffiti on their school as a lark, were arrested and brutally tortured. Disregarding the danger of dissent, the community came to protest in large numbers in the streets. As my interview with Dan Gorman, director of the Shubbak Festival said, “the curtain of fear had been pierced.”

Perhaps, it is unsurprising then, that political posters and street art became so ubiquitous in the Syrian Revolution. The importance of graffiti, murals, and political posters is not unique to Syria or the Middle East. The Cuban and Russian revolutions produced iconic images synonymous with those struggles. The Vietnamese struggle against outside interference produced propaganda posters still sold in Hanoi today. Many of the political posters of the Syrian revolution actually seem inspired by the Palestinian struggle.

As part of the public space, the use of graffiti and murals as a form of expression naturally connects with the general public more so than art hung in galleries. The internet amplified these images beyond their walls and shared their messages with millions of people, not just in Syria, but worldwide. It made street art—vulnerable to weather, bombardment, and whitewashing—permanent. When Abu Malik Al-Shami, the young street artist made famous by his murals in Daraya, was forced to evacuate to Idlib in 2016, he took pictures of his murals, which have since spread online.

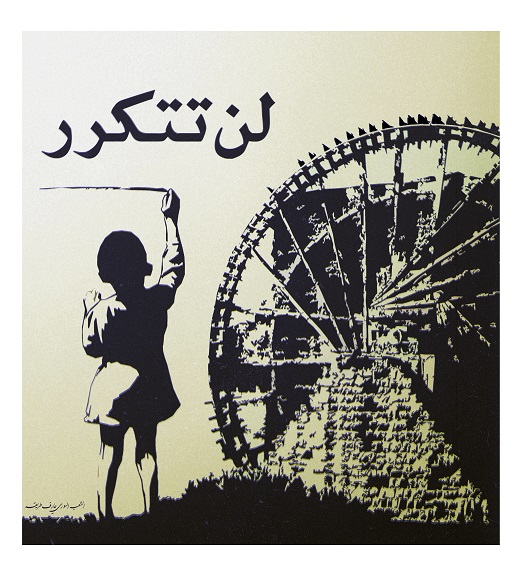

“I’m coming out to protest.” The speaker is female to emphasize women’s role in the revolution. Posters appear courtesy of the anonymous Syrian poster collective Alshaab Alsori Aref Tarekh (The Syrian People Know Their Way), under Creative Commons BY-NC.

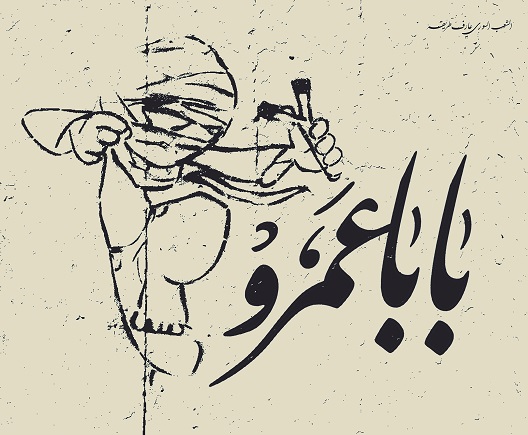

“Baba Amr.” Poster released after the Baba Amr massacre in December 2011. The Syrian version of a boy and his slingshot is based on Zaytoun, the Little Refugee, originally designed by Mohamed Tayeb and inspired by the shelling and hardships inside Yarmouk Palestinian refugee camp in Southern Damascus. Zaytoun, the Little Refugee, is a political, artistic and educational project – from animation to video games – which contests the monopoly of power to write history.” Alshaab Alsori Aref Tarekh interview from Syria Speaks p. 81. Posters appear courtesy of the anonymous Syrian poster collective Alshaab Alsori Aref Tarekh (The Syrian People Know Their Way), under Creative Commons BY-NC.

This mural was painted in a bombed-out school. The student is writing: ‘We used to joke and say, God please destroy the school … and he did.’ Credit Abu Malik Al Shami.

To the regime, nothing could be more horrifying than the ability to disseminate these images widely. This is why the instigators of these ideas were often eliminated. In October 2013, a Palestinian actor named Hassan Hassan, was taken by the regime as he was trying to leave Yarmouk Camp south of Damascus. Hassan had taped sketches of himself mocking the regime. His family was informed of his death two months later. In October 2015, Palestinian award-winning photographer, Niraz Saied, was arrested. Niraz had photographed the conditions of the government-imposed siege on Yarmouk. His images were shared widely around the world. At the end of 2018, his family was informed that he died in prison. These young artists challenged the regime’s narrative that it was the protector of the Palestinian struggle.

The regimes of the Middle East knew the political potential for art. For this reason, it has always been closely monitored. Prior to the revolution, writers and artists in Syria were encouraged to join government-sponsored unions. Syrian dissident artists had to play a delicate balance between a desire to criticize the regime, the risk of publicizing genuine criticism, and the fear that their work would be co-opted as government propaganda, as what Miriam Cooke calls “commissioned criticism.” The regime expertly understood how small allowances of dissent improved their image without lobbing any real threat at the system. After the Russian Revolution succeeded, the Soviets too, understood the possible dangers of artistic free expression. To combat this, they strictly enforced socialist realism, their own brand of acceptable art. Anything that diverged was considered a threat. Sergei Parajanov, a Soviet film director and artist of Armenian descent, who invented his own unique cinematic style, was jailed for years along with other artists during the Soviet period; their work banned across the USSR. Others like artist Aleksander Drevin were killed for their work.

The role of political art and murals may mean little to millions of IDPs in Syria and refugees today. Photos and paintings did not change the outcome for the victims of the Syrian war. Rather than instigating positive change, the protest songs and graffiti put a price on their heads. With Raed Fares and Abdul Basset al-Sarout, icons of the Syrian revolution, killed in just the past few months and the regime edging closer to its goal of taking every inch of Syria, the heady days of the Syrian revolution seem long gone.

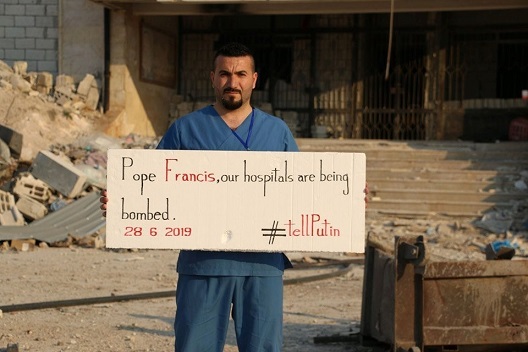

The Pope welcomed Vladimir Putin to the Vatican. Ahead of the meeting, medical staff, teachers, and displaced civilians in Idlib held banners urging Pope Francis to #tellPutin to stop targeting their children, homes, hospitals, and schools. Created June 28, 2019. Source: The Syria Campaign Facebook page.

At the same time, Russia, the Syrian regime’s stalwart ally, is waging a highly effective international war on the cheap; spreading fake news to sow chaos in Europe, former Soviet republics, Syria, and the US. In addition to interfering with the 2016 US presidential election, Russia has spread misinformation on the Syrian war, suggesting that peaceful protestors were part of a global conspiracy, that the civilian victims of aerial bombardment are actors, and that search and rescue workers are terrorists.

However, the Russian and Syrian regimes’ efforts in the media and online betray their desire to win, not just the military war, but the narrative war. In this respect, thousands of political exiles, artists, and cartoonists scattered around the world, have an important role to play along with archivists. Since 2011, various collectives have been archiving hundreds of images, from political graffiti to the infamous political satire posters from Kafranbel. The sheer number of images from across Syria demonstrate how widespread the revolution was and still is.

Kesh Malek (meaning Check Mate) is a civil society organization that aimed to reach the world through its Syria Banksy initiative. Recently, they countered the regime propaganda, espoused by the musician Roger Waters against Syrian search and rescue volunteers, with a poster targeted to the Pink Floyd artist’s misinformed statements. The image in Idlib, Syria depicts Waters carrying an assault rifle with a caption that reads, “A message from Syrians in Idlib to Roger Waters: Hey you, don’t help them to bury the light,” referencing Pink Floyd lyrics.

Mural criticizing Roger Water’s statements on a wall in Idlib, Syria. Credit Kesh Malek Syria Banksy initiative.

These images continue to be a part of Syria’s collective memory, a call to arms, and a venting of frustrations. As Malu Halasa, co-editor of Syria Speaks – Art and Culture from the Frontline, said, the Syrian revolution is a story of “how the street became visible.” In so doing, these works have leaked out of Syria onto our collective conscience, both as pieces of artwork and political expression. Even the establishment British Museum displayed various pieces of Syrian protest art as part of the museum’s “Living Histories” exhibit. The collection featured many works by the anonymous poster collective Alshaab Alsori Aref Tarekh (The Syrian People Know Their Way). The Creative Memory of the Syrian Revolution has also archived hundreds of images with statistics on the words used and the number of walls painted per month.

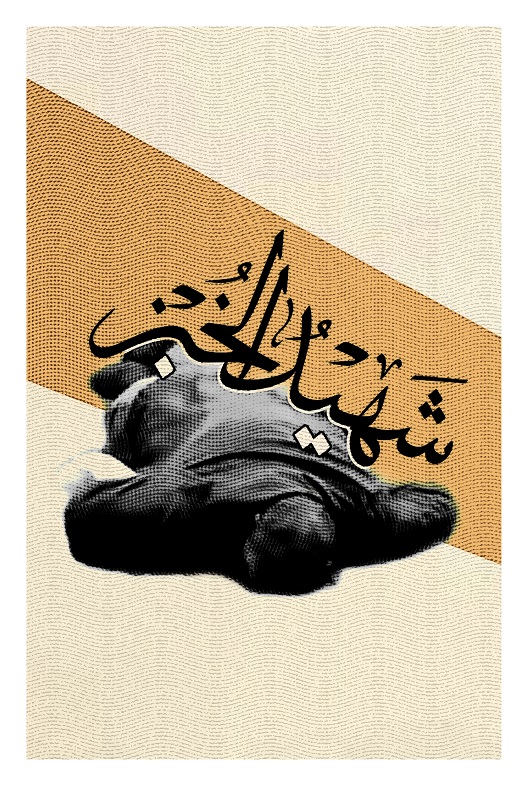

“Martyr for Bread” referring to government-imposed sieges throughout Syria. Posters appear courtesy of the anonymous Syrian poster collective Alshaab Alsori Aref Tarekh (The Syrian People Know Their Way), under Creative Commons BY-NC.

As the situation grows to be more desperate in Syria and the regime continues to bombard marked hospitals without international interference, the number of political images emerging from Syria has dropped markedly since the first years of the revolution. For Syrians, it does not seem as though anyone is listening, but that doesn’t stop some from writing captions in English to reach a wider audience. There is still a movement to save those left in opposition-held areas from aerial bombardment, release prisoners, and find information on the disappeared. For Syrians in danger every day, the war is not over and the narrative war for the history of the revolution has just begun.

Natasha Hall is an independent analyst specializing in the Middle East and refugee and humanitarian crises. Follow her @ArtInExileDC.