In the Gulf countries, we hear about people who do not possess citizenship, like the Bedoon of the Emirates. Because the country’s government does not recognize them as citizens, they do not grant them personal identity, travel documents, or citizenship. While this subject has been studied in the Gulf, there is a comparable situation in Syria and surrounding countries that has been studied much less. There are no official statistics on the numbers of Syrian children born inside Syria over the past few years because of the ongoing military conflict between opposition forces and the regime; for many, there is no path to registration.

In the Gulf countries, we hear about people who do not possess citizenship, like the Bedoon of the Emirates. Because the country’s government does not recognize them as citizens, they do not grant them personal identity, travel documents, or citizenship. While this subject has been studied in the Gulf, there is a comparable situation in Syria and surrounding countries that has been studied much less. There are no official statistics on the numbers of Syrian children born inside Syria over the past few years because of the ongoing military conflict between opposition forces and the regime; for many, there is no path to registration.

Battles between the two sides have resulted in the opposition controlling most of the cities, towns, and countryside of Idlib province, where just over two million people now reside. The Syrian regime has closed all legal and personal identity registration bureaus in areas where they have lost control, denying citizenship as well as the right to an education to thousands of children. This is one of the punishments which the regime is applying with respect to those who leave its domain. Will the thousands of newborn babies who do not have any identity papers to prove their nationality become Syria’s Bedoon?

Families try to register the names of their children according to a document or birth certificate issued either by the hospital in which they were born—the majority of which are field hospitals which surrounding countries do not recognize—or from a Sharia court. However, Sharia court documents are also not recognized by the official institutions of any surrounding countries including Turkey, despite its being a major supporter of the opposition. These hospitals and courts often change their names or are subjected to bombardment and destruction, turning the children into collateral damage. The children of Darayya recently went through this when they were forced to move to Idlib in accordance with the local ceasefire deal removing them from the siege. Most of the children under the age of 5—including both northern internally displaced persons (IDPs) and refugees—do not have documents confirming their lineage or nationality.

The problem is not just limited to nationality and lineage, but includes depriving children of education as most of the schools which fall under opposition control are either completely or partially destroyed. Neither opposition nor government supporters have not put forward any programs capable of halting the spread of illiteracy, especially since, after five years of continuous conflict, many adolescents under the age of fifteen have lost their father and are looking for work in order to support their loved ones. According to a 2015 conference organized by charitable organizations, unofficial statistics indicate that the number of children who have lost one or both parents in northern Syria exceed half a million. There are no indemnities for these children. The incredible challenges that have been put in front of them are forcing them to abandon their education in order to pursue whatever work is available, especially if their mother is unmarried. In addition, armed extremist factions exploit these situations to recruit these children so they can secure a living for their remaining family members.

Officer Hassan from Jabal Zawiya realized the gravity of this situation, so he left Syria and relocated to Turkey with his wife and son. Hassan explains his family’s citizenship circumstances as follows, “I have one son now. I paid thousands of lira so that I could obtain a family register as if I were just visiting [Turkey], so that I can register my son in Turkey and an ID can be obtained for him from the Turkish government giving him some rights, like education for example. I possess my officer ID card and my wife has her Syrian ID card, meaning both of us hold Syrian nationality. As for our son, he does not have identity documents that would enable him to obtain citizenship in the future. The regime has classified me as a terrorist and I have no rights. I cannot have another child right now because his situation would be extremely complicated.”

There are many who, unlike Officer Hassan, are unable to escape Syria. Their children suffer as a result. Sometimes, their education is limited to some Quranic verses learned in a small tent in one of the camps due to the total absence of qualified educational personnel, who have been part of the exodus from Syria. Those living in the camps are also the poorest. In the regime era, they were persecuted—they still are. The only difference is that their communities have moved from being authoritarian societies dominated by the Assad family to having new leaders but being equally oppressive. Many find themselves in societies imbued with a religious character and led by militants instead of civilian leadership. Some of these militants are ex-convicts who, amid widespread poverty, seized the opportunity to become commanders.

According to UN statistics as of 2015, there are more than 13,500,000 Syrians in urgent need of aid, including 12,200,000 in need of protection, 4,000,000 of whom are undernourished and 4,500,000 children who are not enrolled in school. The Syrian people will not recover from the damage caused by the war anytime soon.

The international community’s lack of action has left a humanitarian catastrophe. This situation has opened the way for extremist organizations like the Islamic State, Jabhat Fateh al-Sham (previously known as the Nusra Front), and others to recruit hundreds of children and minors. The Syrian regime has also recruited youth, both by force and by employing emergency laws allowing the government to reenlist anyone who already completed his mandatory military service. It is not uncommon to hear stories about multiple brothers from one family who are each fighting for a different side. Likewise, many of the prisoners captured by regime forces are twenty years old or younger, as are the dead on both sides. This is especially true for the opposition factions, which are turning to recruiting youth because of the large depletion in their ranks.

While the situation in Syria has become increasingly dire, Syrian refugees are cautiously monitoring the election of Donald Trump. The future of Syria depends on saving future generations, but Trump’s focus on fighting terrorism, coupled with his readiness to work with Russia and the Syrian government, will not save Syria from those who are destroying it. That will become clear in the coming years as the spread of ignorance, illiteracy, and poverty creates fertile ground for extremism—the very fear upon which the Syrian regime plays.

In Turkey, if you walk the streets of the cities of Istanbul, Gaziantep, and Antakya, you will see children selling small tissue boxes at traffic lights, risking their lives by navigating between the cars. I saw an eleven-year-old Aleppo girl from Salaheddin District selling tissues for half a Turkish lira in front of one of the Syrian clinics, receiving a great deal of sympathy from the clinic’s visitors. I asked her where her father was and she replied, “My father is a martyr. He died in Aleppo and I live with my sister, brother, and mother selling tissues as I need to earn 30 Turkish lira each day.” So I asked her, “How many hours do you work to obtain that amount?” She replied, “I work more than six hours each day. My brother also works like me.” I asked her, “Do you go to school?” She answered, laughing, “Yes, I go, but not every day. Maybe two or three days during the week.” Then, I asked her, “Are you not afraid that your friends from school will see you?” She replied, “My school is in Qurtash, one of Gaziantep’s suburbs. They won’t come here.”

Saleem al-Omar is a freelance journalist who has written for Al-Jazeera, Alquds Alarabi Newspaper, Arabi 21, and Syria Deeply.

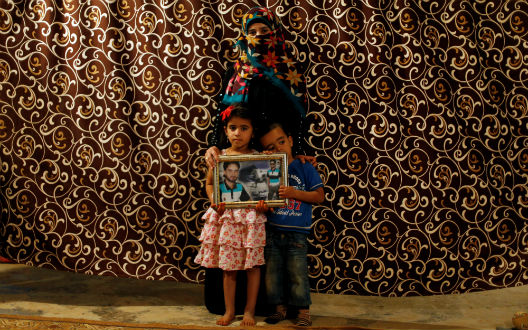

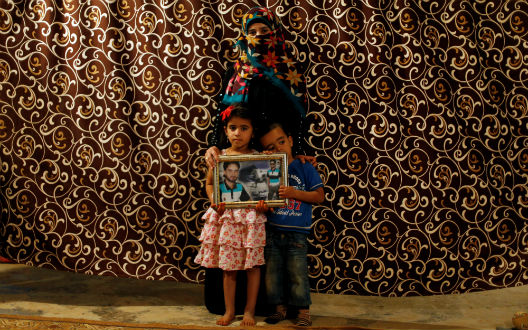

Image: Photo: Mageda Armous, 25, the widow of a rebel fighter poses for a photograph with her children, as they hold a photograph of their late father in Zaatari camp in Jordan October 8, 2016. Armous's husband was killed during fighting againt forces loyal to Syria's President Bashar al-Assad in Daraa. REUTERS/Ammar Awad