The choice to emigrate from Syria is a difficult one for Syrians. Despite the war and oppressive rule of extremist groups such as the Islamic State, leaving Syria means braving the unknown and feeling one has abandoned his friends and country. Karam, who asked to only be identified by his first name, said, “I am betraying my revolution, I am betraying my homeland,” when he immigrated to Germany after surviving over four years of war. Originally from the western side of Aleppo city, when the fighting split the city into a regime-controlled western portion and opposition-controlled eastern portion in 2012, he decided to relocate to the eastern side.

The choice to emigrate from Syria is a difficult one for Syrians. Despite the war and oppressive rule of extremist groups such as the Islamic State, leaving Syria means braving the unknown and feeling one has abandoned his friends and country. Karam, who asked to only be identified by his first name, said, “I am betraying my revolution, I am betraying my homeland,” when he immigrated to Germany after surviving over four years of war. Originally from the western side of Aleppo city, when the fighting split the city into a regime-controlled western portion and opposition-controlled eastern portion in 2012, he decided to relocate to the eastern side.

“Between getting arrested by Assad forces or bombed by them, I chose the latter,” he said. There, he worked as a fixer for opposition forces, accompanying rebels to the front lines, guiding them through the streets of his childhood and providing the coordinates of military targets so that rebel forces avoided shelling civilians. Civilian protection has always been his priority, and so he would photograph damaged residential areas for local news agencies and provide medical aid to injured civilians. His work with armed groups never stopped him from taking part in demonstrations against the regime and opposition groups that committed violations against civilians.

As the war dragged on, though, he lost hope of liberating his city. This past summer he immigrated to Germany, but instead of feeling relieved that he left the war, he feels he abandoned the revolution. Despite the war, he misses his time in Syria, “even the horrific bits where you are frightened of a nearby barrel bomb. I feel useless here. I often wish I could be with my activist friends.” So strong is his desire to go back that he is already planning his return after finishing his university degree.

Since leaving, Karam feels that he has lost the right to post online about the revolution. “I am away now and don’t have the right to comment or tell those whom I left behind what they should or shouldn’t do.” When he posts a picture of Berlin, his former companions criticize him for leaving, saying, “Do you really want all those defending Syria from Assad and the Islamic State to join the beautiful land you are in now?” When he posts on Facebook wishing safety for friends who are making the dangerous trek to Europe, those still in Syria accuse him of encouraging others to join him in Germany so he “won’t feel the guilt for leaving the revolution half-way through.”

Those that do leave find it best to stay engaged and maintain some level of activism, out of a desire to enact change but also because if they do not, they find themselves depressed and frustrated as Karam described. For some Syrians, arriving in a Western country is a chance to raise awareness about what is happening in Syria and advocate for Western intervention.

Despite the media attention given to refugees and the difficult journey they face going to Europe, some Syrians who remain in their country have no sympathy for them. A mother of two who refused to escape to Turkey and stayed in Aleppo said to me, “Whatever they are going through, it can’t be compared with our daily suffering. At least they are choosing [to leave] for personal gain for themselves and their children, while we are risking our lives and our children for our country, [a country] that once was theirs too!”

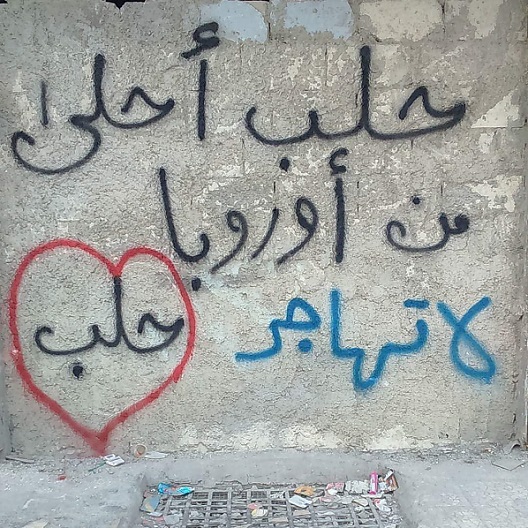

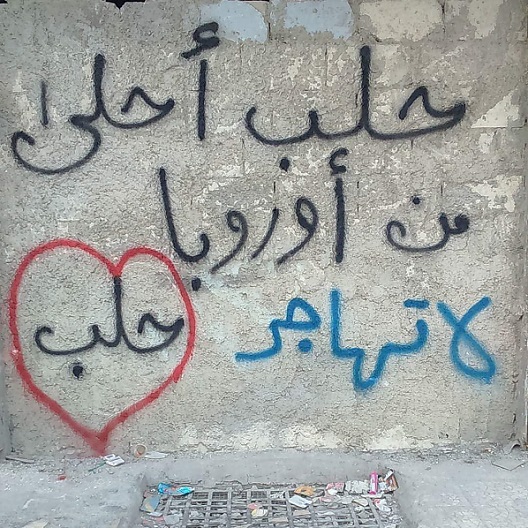

A movement against leaving Syria has started to take root. Activists graffiti walls with messages like, “Our town is more beautiful than Europe, do not immigrate.” It started in Binnish, a small town in northern Idlib, before reaching the walls of Aleppo and other rebel held areas.

Fleeing to Turkey does provide immediate relief from the shelling and fighting, but there many Syrians feel they are in permanent limbo. It is difficult for Syrians to legally register their personal affairs, such as marriages, because many lack their Syrian legal documents that the Turkish government requires as the Syrian government does not provide these documents to Syrians who are on the government’s wanted lists. Many of the 2.2 million refugees in Turkey cannot get new passports or renew old ones. The recent EU-Turkey talks might ease the process for Syrians to get a work permit in Turkey, and provide financial support for schooling, but until a formal agreement is signed, Syrians remain leery of raising their hopes.

For activists and fighters most involved in conflict, leaving to a neighboring country is bad, but traveling to Europe to build a new life is even worse. Hamza, a doctor at a field hospital in Aleppo, said, “To whom are they leaving their county? Don’t they belong to it, too? No wonder extremists and the regime are winning, because we are becoming less and less as people leave, and then when peace comes and those of us [who stayed] are killed or disabled they claim they want to come back to rebuild the county?” Some Syrians see no difference between staying in Turkey and seeking refuge in an EU country. “We are away from our homes anyway, what is the difference between southern Turkey and Amsterdam to me, but better opportunities and a future for my little girl?” said Abdul Rahman, a 25 year-old activist.

The Syrian revolution-turned-war is nearly five years old, but the “refugee crisis” that it has created is framed in the media as a Western problem. The personal aspect of what Amnesty International called the worst humanitarian crisis of our time is forgotten in debates of national security and the United States’ and European Union’s willingness and capacity to absorb refugees. What is missed in these discussions are the contradictory feelings of potential migrants: the desire to survive and provide a better future for one’s family and oneself, but also the desire to stay and contribute to their country.

Zaina Erhaim is a Syrian journalist who works as a project coordinator for the Institute for War and Peace Reporting in Turkey, won the Peter Mackler award for courageous and ethical journalism, and Reporters Sans Frontieres named her the journalist of the year for her work inside Syria and training citizen journalists working inside.

Image: (Photo: Author. Graffiti on a wall in Aleppo that reads, "Aleppo is more beautiful than Europe, don't emigrate from Aleppo.")