A new documentation system in the Turkish-administrated region in northern Aleppo designed for security and administrative purposes seems to ignore the legal status of local residents; many of which are internally displaced peoples (IDP)s that are Syrian or Palestinian. The system raises concerns from displaced Palestinian refugees about their internationally recognized legal refugee status and their ability to preserve their Palestinian identity within the larger Syrian population.

In May 2018, around 500 families of Palestinian refugees were forced to immediately evacuate Yarmouk camp in southern Damascus as part of an agreement between the Syrian government and various armed groups. Palestinians in Yarmouk were not allowed to collect their belongings and official documents from their homes. The evacuation came at the end of an unprecedented military offensive by the Syrian government, which forced people to take refuge in opposition-controlled neighborhoods.

The evacuation convoys headed in two directions supervised by the Russian military police and accompanied by the Syrian Red Crescent. Some went to Idlib province or into Turkish controlled areas in the north. The majority of refugees preferred to settle in Turkish-administrated areas of Euphrates Shield and Olive Branch in northern Aleppo; given the relative stability and services provided by the governing authority and local organizations.

The new arrivals joined 1,500 Palestinian families with similar circumstances from Palestinian camps in rural Damascus and Aleppo. Turkish authorities placed families among two large displacement camps. The first camp, Dier Ballout in the city of Afrin, includes hundreds of basic tents occupied by families. The second camp, the Center for Temporary Residence in Azzaz city, was initially a holding area before it evolved into semi-permanent housing. The camp consists of large dormitories each occupied by 150 men and women separately.

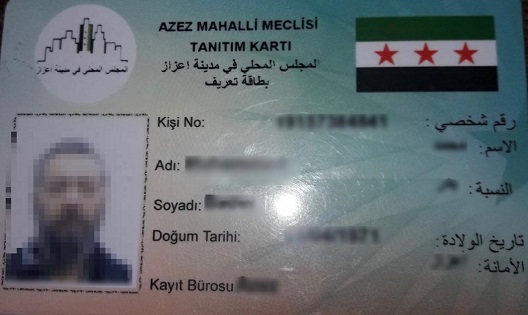

However, another issue of serious concern is the governing authorities’ decision to terminate all documents issued by the Syrian government, and the implementation of a new documentation system and identification cards for all displaced Syrians. A month later in June 2018, the local councils of several areas in the northern countryside of Aleppo issued identification cards to all residents. The photo ID is written in Arabic and Turkish. It includes the national ID number, electronic fingerprint, and it states the holder’s personal information. To ensure the registration of all residents, the governing authority required residents to obtain the new ID for school registration, employment opportunities, access to health care facilities, and receiving legal approvals. All collected personal data is stored with the Turkish civil registry system.

Photo: Provided by Author, March 2019

Photo: Provided by Author, March 2019

The new IDs are part of a larger documentation effort led by the de facto governing authority, the Turkish government. The new system enables the governing authority to count the residents of the region in what is now a makeshift refugee camp to hundreds of thousands of civilians displaced from various parts of Syria. It also provides IDs for many Syrians who lost their identity cards during the war. Further, it supports the security efforts by the Turkey-backed Syrian forces to ensure that the area does not hold members of ISIS and Kurdish-dominated Syria Democratic Forces (SDF).

Displaced Palestinian refugees have real concerns about the new documentation system because of the lack of information and transparency from the Turkish authorities. Many believe their internationally recognized status is threatened by this new Turkish-run system, as it makes no mention of the resident’s legal status. Instead, it treats all residents as displaced Syrians. The Turkish-run system differs from the Syrian government’s system for Palestinian refugees which indicates their origin and internationally recognized legal status as Palestinian refugees with the General Administration for Palestine Arab Refugees (GAPAR).

Ammar al-Qudsi is a paralegal specialized in civilian records of Palestinian communities in Syria and currently displaced from Yarmouk camp to northern Aleppo. Al-Qudsi explains that what is driving concerns is the uncertainty of the Turkish-run system’s implications on their legal status as Palestinian refugees. They fear that the lack of proper documentation for Palestinians may dilute their national identity as Palestinian refugees within the larger Syrian population. In addition, they fear they will lose proof of legal status and endanger their consequent rights including the right of return, protection, and services.

The displacement of the Palestinian population brought about immense challenges by uprooting families into poor living conditions. Since the displacement, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestinians (UNRWA) is unable to communicate with Palestinians in Syria to provide them protection and services. In addition, Palestinian refugees lost access to their traditional representatives in Syria, such as armed and political Palestinian factions.

Palestinians called on UNRWA to carry out a documentation process in their new area of residence, pointing out that they are still inside the Syrian territory, which is part of the organization’s operational area. The absence of UNRWA in the region increases the fear among Palestinian refugees. “They [Palestinians] consider UNRWA their guardian in times of hardship,” Qudsi says, adding the organization is expected to be present in their new residing areas.

Amid enormous challenges, UNRWA continues its normal activities in the Syrian government-run areas. However, the situation is different in the opposition-controlled areas because of security and compliance issues with the Syrian Authority’s restrictions. On several occasions, UNRWA managed to reach Palestinian refugees besieged in Yarmouk, after being granted approval by the Syrian government along with security guarantees from armed opposition. However, the organization has not yet reached the displaced Palestinians in northern Syria or communicated with them.

In November 2018, then-UNRWA spokesperson Chris Gunness told MENASource that the organization has not been able to reach out to displaced Palestinian refugees due to a lack of operational capacity. Gunness described UNRWA in Syria as buildings located across various areas. He noted that UNRWA does not operate where displaced Palestinians are currently residing and lacks the medical, educational, and operational capabilities to reach them and provide services, adding “they have to come to us, we cannot go to them.” However, the organization did adopt atypical strategies to reach Yarmouk residents when they were under siege by the regime. Qudsi suggested that UNRWA should consider working with local NGOs present in the area.

Lawyer Francesca Albanese is a former UNRWA employee and a researcher on the status of Palestinian refugees in international law. Albanese says that the status of Palestinian refugees is anchored in international law and no one can change this unless and until their refugee status and claims are resolved in line with relevant General Assembly resolutions. The legal status of Palestinian refugees in Syria is based on registration with GAPAR, as well as with UNRWA for protection and assistance. Temporary documentation should not alter this status.

Albanese stresses that protection and assistance by the governing authority for displaced Palestinian refugees should be provided following the principle of “do no harm” until the end of the cessation of the hostilities and their return to their homes. She notes the fear among the displaced Palestinians is understandable given previous Palestinian communities’ experience of losing their legal status as a result of national and international shifts, such as what happened to Iraq’s Palestinian communities in the aftermath of the war in Iraq in 2003.

Albanese concludes that despite the UNRWA’s physical difficulties in reaching out to this group of Palestinians, the organization should be able to advise them on their concerns and intervene with the competent authorities as needed. It is legitimate that Palestinian refugees demand to have their status properly recorded on any documentation they obtain in order to assert their status and rights.

Musaab Balchi is Palestinian-Syrian journalist from Yarmouk camp. He covered the situation on the ground for Palestinian communities in Syria until late 2013. He recently graduated from George Mason University with a Master’s of Arts in Middle East and Islamic Studies. He is a monthly contributor to the Arabic section of Refugees and Migrants Project (RAMP), Jadaliyya E-Magazine. Follow him on Twitter @MusaabBalchi.

Image: Photo: Soldiers walk past damaged buildings in Yarmouk Palestinian camp in Damascus, Syria May 22, 2018. REUTERS/Omar Sanadiki