A chemical attack by regime warplanes in the Syrian province of Idlib has left over 70 civilians dead and at least another 100 seeking treatment for exposure to toxic gases. Though details are still being revealed, initial reports suggest that attack used sarin gas, the same deadly gas the regime used in an attack on Ghouta in 2013. After Ghouta, Russia and the United States reached a deal in which the Syrian regime agreed to join the Chemical Weapons Convention and allow its stockpiles to be destroyed. Yesterday’s chemical attack was therefore unexpected, but can be understood both within both an international and domestic context, Atlantic Council experts say.

A chemical attack by regime warplanes in the Syrian province of Idlib has left over 70 civilians dead and at least another 100 seeking treatment for exposure to toxic gases. Though details are still being revealed, initial reports suggest that attack used sarin gas, the same deadly gas the regime used in an attack on Ghouta in 2013. After Ghouta, Russia and the United States reached a deal in which the Syrian regime agreed to join the Chemical Weapons Convention and allow its stockpiles to be destroyed. Yesterday’s chemical attack was therefore unexpected, but can be understood both within both an international and domestic context, Atlantic Council experts say.

Internationally, the attack should be viewed against a backdrop of recent statements made by the Trump administration officials about US policy not being focused on removing Bashar al-Assad as president of Syria. Domestically, the attacks can be viewed as a punishment of holdout rebel areas standing in the way of a consolidation of power by the regime, they add.

Why did Assad carry out this attack now?

Faysal Itani: The use of chemical weapons by the Assad regime was somewhat surprising, but not difficult to explain despite the risks it entailed in the past. The mostly likely rationale is not an elaborate calculation of international trends and reactions by the regime, though that may have factored into the decision.

Rather, there is actually a military and psychological rationale for punishing rebel areas from which the armed opposition dares to continue mounting attacks, disrupting regime plans to consolidate its authority over all of western Syria.

Observers may puzzle over why Assad would take such a risk after narrowly escaping military action for using Sarin gas in August 2013, but the Trump administration had clearly communicated its acceptance of Assad, which not even the Obama administration that spared Assad in 2013 had done.

Frederic C. Hof: Assad’s chemical attack reflects his sense of total impunity. Recent administration statements to the effect that the political fate of Assad himself is not a central concern may have fed that sense of impunity. Assad may have concluded that Obama administration’s blind eye to civilian protection in Syria had continued seamlessly into the Trump administration. Still, it is hard to blame newly minted senior administration officials for underestimating the cruelty, cynicism, and bloody-mindedness of Bashar al-Assad. If they were mistaken in speaking out, it is not likely to be a mistake repeated.

What reaction can we expect from the US administration?

Frederic C. Hof: The chemical attack on Syrian civilians by the Assad regime presents the Trump administration with a stark choice: respond forcefully with action – perhaps with strikes on the air base from which the attack was launched – or adopt the action-free, rhetoric-rich policy of the Obama administration as its own.

No one wants to invade and occupy Syria. No one is planning violent regime change. But Assad kills with absolute confidence supported by an absolute sense of impunity. Where is it written that pilots dropping weapons of terror on children should do so unopposed? Who has decided that air bases launching terror missions should be immune from the consequences of the evil they do? Is exacting a price – ending the free ride for mass homicide – beyond the wit of Washington and the West? Is the risk of acting so huge as to justify the horrific costs associated with inaction? Does “Never Again” really mean, “Well, maybe just this once?”

President Trump will either adopt his predecessor’s Syria policy as his own – reaping in full the mixture of contempt and pity garnered by the ex-president from friend and foe alike – or he will act to end the Assad regime’s free ride for mass murder. Letting that ride proceed unopposed would suggest that the battle against violent extremism in Syria and beyond is something less than a serious undertaking. Assad has communicated his defiance and contempt. The reply will help define the new administration.

Faysal Itani: Whether or not Assad miscalculated will become clear in the hours ahead as the Trump administration contemplates its options, both military and diplomatic. There is no indication yet however of an intention to escalate.

Frederic C. Hof is director of the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East.

Faysal Itani is a senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East.

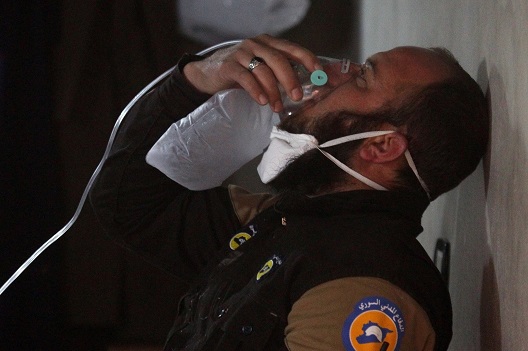

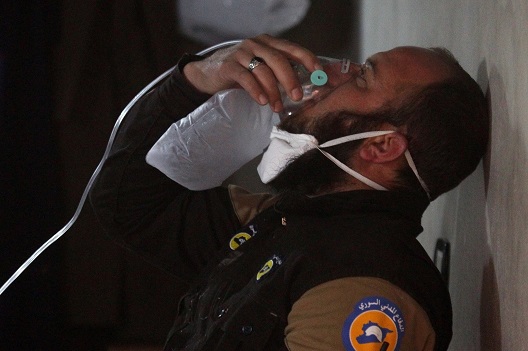

Image: Photo: A civil defence member breathes through an oxygen mask, after what rescue workers described as a suspected gas attack in the town of Khan Sheikhoun in rebel-held Idlib, Syria April 4, 2017. REUTERS/Ammar Abdullah