Turkey’s natural gas demand has grown exponentially since the late 1980s, when Turkey imported only a few billion cubic meters (bcm) a year. Annual imports have grown to around 50 bcm with strong demand from combined cycle gas turbines (CCGTs) and households (55 bcm in 2017), making Turkey one of the biggest markets in the world. Thanks to recent investments in gas infrastructure, especially in liquefied natural gas (LNG), Turkey’s daily gas entry capacity to grid reached 320 million cubic meters (mcm). The goal is to increase this capacity to 400 mcm/day.

There is return on these investments for the country. While Turkey’s gas supply security is enhanced, the domestic market benefits from the increasing competition in the global gas market. With LNG, Turkey can further diversify its gas supply sources and the state-owned gas company, BOTAS, can decrease the weighted average cost of imported gas. Moreover, post-2021 market conditions may herald a new era.

A new era for LNG

Turkey’s LNG imports have been on the rise over the last several years, making LNG a key component of its long-term diversification strategy.

Indeed, Turkey is on the threshold of a new era for LNG. By expiring long-term, oil-indexed BOTAS contracts with worrisome take-or-pay provisions after 2021 (more than 35 bcm/year between 2021 and 2025), which is called “Energy Transition 2.0” by Alparslan Bayraktar (the Turkish deputy energy minister), the country aims to sign fresh contracts in accordance with new market conditions.

Turkey found the solution in natural gas in its quest for a cheap energy source to fuel its developing economy and to combat air pollution. BOTAS Marmara Ereglisi LNG Terminal, Turkey’s first LNG terminal, was commissioned in 1994 in order to meet seasonal consumption peaks and enhance security of supply in the lack of underground storage facilities.

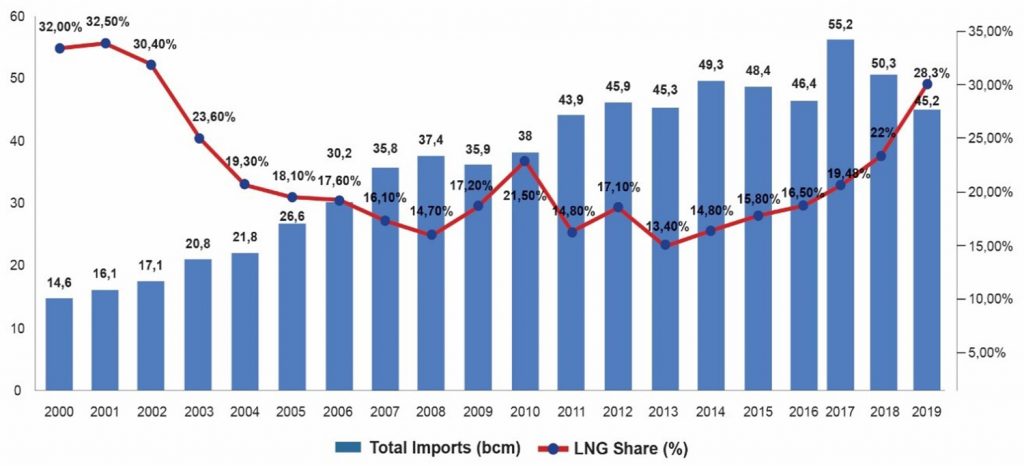

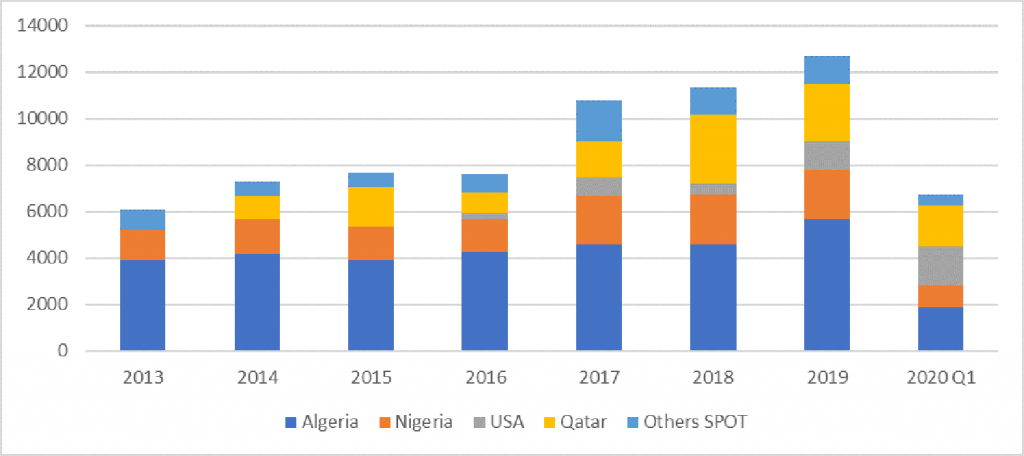

While Turkey secured more than thirty percent of its natural gas demand with LNG in the early 2000s, LNG’s total supply share gradually decreased after Turkey signed long-term contracts with Iran, Russia, and Azerbaijan. This decrease has reverted to a steady upward trend since 2013; Turkey imported almost the same amount of gas in 2013 and 2019, with the share of LNG making a huge difference—6.1 bcm in 2013 and 12.7 bcm in 2019, which is an all-time high.

There are two reasons for this: the price and Turkey’s lack of import capacity back in 2013. In 2013, LNG prices were around $15 per one million British Thermal Units (mmbtu) after the Fukushima accident, meaning that Turkey was importing pipeline gas that was cheaper than LNG. Turkish daily send-out capacities of LNG terminals and overall gas injection capacity to grid was 36 mcm/day and 185 mcm/day, respectively, in 2013, not allowing for the coverage of peak demand in winter, which Turkey could not cover with imports due to infrastructure constraints.

This changed dramatically in four years. A rupture in bilateral relations after Turkey downed a Russian jet in late 2015 triggered supply security discussions. Turkey’s heavy reliance on Russian gas, which was more than fifty percent of total imports, triggered a public debate on supply security followed by rapid and huge investments in LNG import terminals—namely to two FSRU vessels—and tripled send-out capacities in LNG terminals—around 117 mcm/day.

Price advantage?

There have been a tremendous number of articles on the impact of US LNG on global gas markets since the first LNG cargo left the Sabine Pass terminal in Louisiana; Australia, Russia, Papua New Guinea, and Cameroon substantially increased their LNG supplies as a result. On the demand side, however, there is a different story. The slowdown of global economies, increasing shares of renewables, mild winters, and the COVID-19 pandemic have suppressed global LNG demand. Therefore, LNG prices have been declining since September 2018, when $10/mmbtu levels prevailed. Today, Europe and Asia delivery spot LNG cargos are being traded below $2/mmbtu. BOTAS has been importing all spot cargos at TTF-prices since late 2019.

While Turkey’s main LNG suppliers—Algeria, Nigeria and Qatar—largely keep their market share, spot imports, especially from the United States, are on the rise. Turkey’s 2020 first quarter LNG imports (6.7 bcm) account for more than half of its entire 2019 imports, making it the third biggest European US LNG importer following Spain and the UK.

Naturally, price is the most important factor in LNG offtakes of BOTAS. According to the price assessments of Argus and ICIS, BOTAS’s quarter one pipeline gas costs were between $6-7/mmbtu. BOTAS can import LNG with considerably lower prices than pipeline gas.

According to the Turkish Energy Market Regulatory Authority data, BOTAS purchased gas from Iran at its annual take-or-pay (ToP) levels and could not meet ToP obligations in Gazprom contracts. Due to the high prices of Gazprom, private sector importers could only import 1.3 bcm overall, which is substantially lower than the cumulative 8 bcm ToP of private companies. Obviously, Gazprom managers are not happy with the decrease of Gazprom volumes from 28.7 bcm to 15.2 bcm in just two years. This rings an alarm bell not only for private sector gas importers but also for Gazprom. All private sector companies supply gas through TurkStream, and an increase in ToP volume risks that this line will remain idle. Moreover, Gazprom’s pricing strategy in the Turkish market will be even more critical. 8 bcm of Gazprom contracts (four for BOTAS and four for private companies) will be expiring at the end of 2021, as the entire volume will be sold via TurkStream.

Future of the market

Turkey aims to transform itself into a gas trading hub rather than serving only as a transit country. With a unique geopolitical position merging exporters and importers, 327 licensed and active companies in every part of the gas value chain, and 50 bcm/year average consumption, Turkey is one of the biggest natural gas markets in the region and the world. Moreover, Turkey can be a key gas actor in helping Eastern European and Balkan countries strengthen their energy supply security.

Turkey, however, should progress further in market liberalization, one of the key pillars of liquid gas hubs along with physical infrastructure and regulatory framework. The global natural gas market outlook disrupted by COVID-19 provides Turkey with a unique opportunity to achieve natural gas market liberalization underlined by Natural Gas Market Law No: 4646. The Turkish Ministry of Energy regards Turkey’s power market liberalization as a model for the gas market liberalization in “Energy Transition 2.0.” In this process, more flexible contract conditions, terms, and pricing structure will be aimed for. Therefore, LNG can be key in Turkey’s gas sector transformation with the more active involvement of private companies.

Eser Özdil is founder of Glocal Group Consulting, Investment & Trade @eserozdil

The views expressed in TURKEYSource are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Atlantic Council, its staff, or its supporters.

Further reading:

Image: General view of liquefied natural gas (LNG) import terminal in Marmara Ereglisi some 100 km (62 miles) west of Istanbul, January 6, 2009. REUTERS/Osman Orsal (TURKEY)