On a recent warm summer night, Ilya Lukash sat in a bar near Kyiv’s trendy Kontraktova Square, drinking a beer and chatting with his friends in Ukrainian, Russian, and English. In a red T-shirt emblazoned with patriotic Ukrainian slogans, he could easily have been any one of the countless young, educated, pro-democracy Ukrainians who in February 2014 came out to support the Euromaidan movement that toppled President Viktor Yanukovych.

On a recent warm summer night, Ilya Lukash sat in a bar near Kyiv’s trendy Kontraktova Square, drinking a beer and chatting with his friends in Ukrainian, Russian, and English. In a red T-shirt emblazoned with patriotic Ukrainian slogans, he could easily have been any one of the countless young, educated, pro-democracy Ukrainians who in February 2014 came out to support the Euromaidan movement that toppled President Viktor Yanukovych.

But Lukash, 28, wasn’t in Kyiv for the Maidan, he’s not from Ukraine, and eighteen months ago, he didn’t even speak Ukrainian. Rather, Lukash is a citizen of Kyrgyzstan—and a pro-Western blogger who supported the Euromaidan from afar, and paid a high price for it. In March 2014, as Russia’s “little green men” were quietly seizing the Crimean peninsula, he fled Kyrgyzstan after Kyrgyz nationalists pilloried him as a “gay activist” during an anti-Western protest.

Caught between fighting for his beliefs and Russia’s deteriorating ties with the West, Lukash chose to support Ukraine—the land of his ancestors—as it struggles for a European, democratic future. Meanwhile, his native Kyrgyzstan has been moving closer to Moscow, and the Ukraine crisis seemed to confirm the government’s growing alignment with the Kremlin. Lukash didn’t know it, but he was on a collision course with his country’s changing politics.

Now exiled in Kyiv, Lukash follows events back home with concern and said he still considers himself “a Kyrgyz patriot.”

Maidan and anti-Maidan

Descended from evangelical Christians who fled Ukraine in 1932 during the first wave of a Soviet-engineered famine there, Lukash grew up in a pious Baptist community in Jalalabad, Kyrgyzstan. After moving to Bishkek, the capital, he came to prominence as a blogger and liberal activist, starting with a protest called “Putin, hands off Kyrgyzstan” in 2010.

It helped that Kyrgyzstan—a country often lauded as the “Switzerland of Central Asia” for its alpine vistas—was for years the region’s most open and democratic country. It’s also had a turbulent history; twice, in 2005 and 2010, the Kyrgyz people overthrew corrupt presidents who had overstepped their authority. Its government had long tried to balance relations between Moscow and Washington, even hosting airbases for both superpowers.

However, Kyrgyzstan was also one of the most pro-Russian countries in the former Soviet Union. Lukash was widely criticized for rallying in support of the Russian feminist punk group Pussy Riot, for opposing Kyrgyzstan’s entry into the Russia-led Eurasian Economic Union (EEU), for speaking out against a Bishkek court’s 2012 decision to ban a film detailing the lives of gay Muslims, and for taking part in a nude photo shoot to challenge restrictive gender roles.

Meanwhile, after his election in 2011, President Almazbek Atambayev began bringing Kyrgyzstan closer into Moscow’s orbit. In a move sure to please the Kremlin, the Kyrgyz government declined to extend the Pentagon’s lease on the Manas air base, which since 2001 had been used to support the war in Afghanistan; the base closed in June 2014. Then, Kyrgyzstan started the process of joining the EEU. And, perhaps most ominously, the Kyrgyz parliament began weighing two bills modeled on Russian laws—one that would punish “gay propaganda” to minors with up to a year in jail, and another requiring NGOs that receive foreign funding to register as “foreign agents.”

But, by late 2013, as Kyrgyzstan’s conservative trend became increasingly clear, Lukash had largely given up civic activism, focusing instead on two high-paying media and advertising jobs, a girlfriend, and many opportunities for overseas travel. But then the Euromaidan protests in Kyiv began and Lukash—who had long opposed Russia’s policies in Kyrgyzstan—simply couldn’t ignore them.

Soon, however, Lukash found himself the target of a concentrated online smear campaign by pro-Russian activists and media he believes received funding from the Kremlin. He was variously accused of being a right-wing fascist, a pedophile, a lobbyist, and a lobbyist for the West. Unknown individuals created duplicates of his Facebook and Twitter profiles and posted claims that he had met with US Embassy officials and had decided to organize Euromaidan protests in Kyrgyzstan.

But criticism was hardly new to Lukash, so he mostly ignored the bad press.

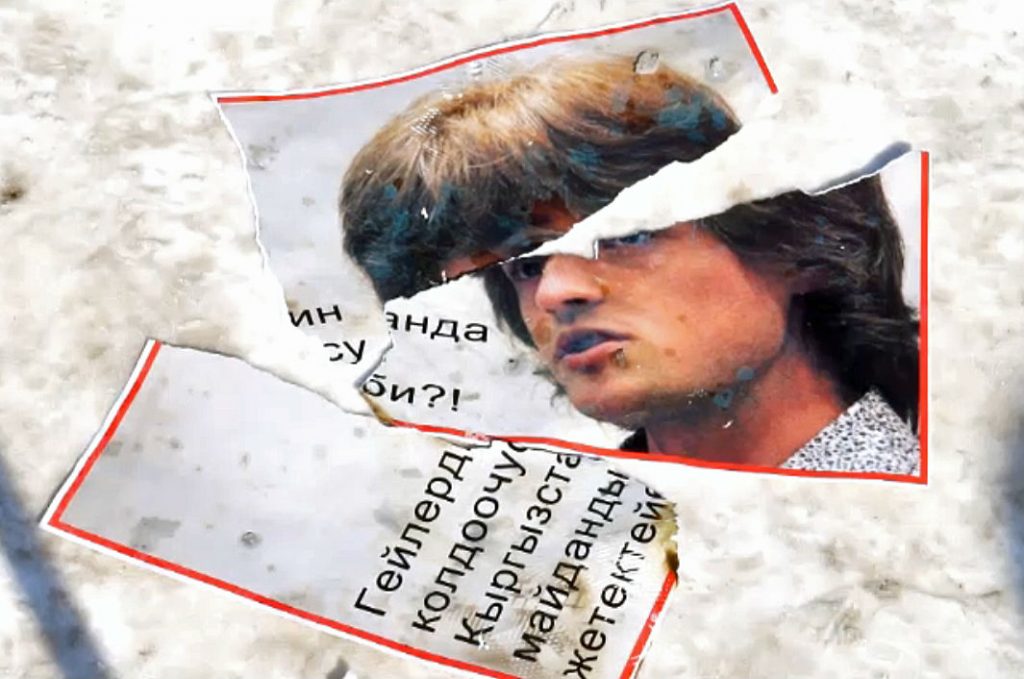

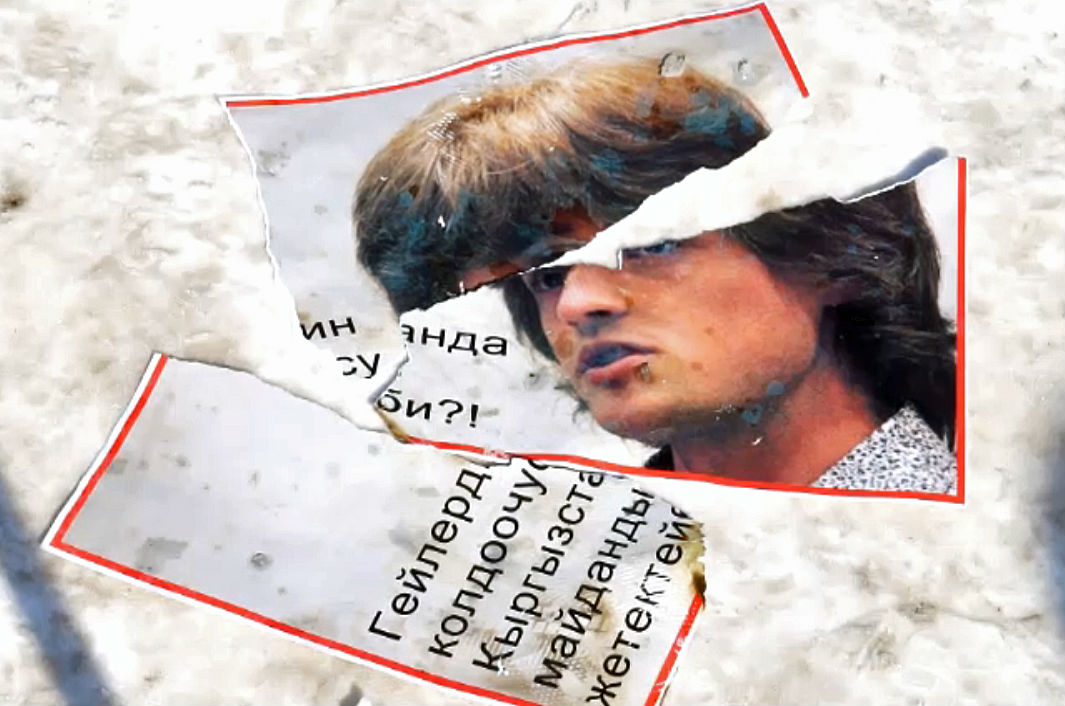

Then, in late February 2014, journalists informed Lukash that the Kyrgyz nationalist youth movement Kalys had called him a “gay activist” and was planning to burn his photograph at an upcoming rally. Lukash contacted Jenish Moldokmatov, the movement’s leader, and tried to explain that he had not led protests for LGBT rights, and that any claims he was organizing a Euromaidan-style revolt in Kyrgyzstan came from fake copies of his social media accounts.

“I may think what I think,” Lukash recalls telling the nationalist leader, “but I haven’t made any public statements in support of gay rights.”

But Moldokmatov, a provocative newcomer to Kyrgyz politics, didn’t care. Instead, he invited Lukash to come explain himself at the rally. Worried about his own safety, Lukash declined.

Thus, on February 27, 2014, before eighty members and supporters of Kalys, Moldokmatov declared Lukash a coward and a “gay activist” and then theatrically burnt his portrait in front of the US Embassy. Kalys also denounced Western-funded NGOs, reform-minded Kyrgyz parliamentarians, childhood masturbation, European sex education, and, of course, the Euromaidan.

But the burning of Lukash’s portrait was the rally’s most memorable moment, and “gay activist” its most scandalous accusation. The protest was widely covered by Kyrgyz media, catapulting both Kalys and Lukash to prominence. Yet this was hardly the kind of attention Lukash wanted.

Famous for the wrong reasons

Soon, people began to recognize and harass Lukash in public. He received anonymous, threatening phone calls so frequently that he eventually turned off his cell phone. One day, a group of young men in a café started pointing at him. He overheard one of them discussing by cell phone whether he should “beat Lukash right here, or confront him in the street.” He even had to vacate his apartment for three nights after a band of aggressive young men gathered outside his window. Finally, he was quietly fired from his two jobs after individuals claiming to represent the GKNB—Kyrgyzstan’s state security agency—threatened his bosses with “inspections” if they kept him on staff.

All this, Lukash alleges, was part of a campaign by Russian-based individuals to silence him.

But not everyone agrees. Moldokmatov says Kalys is entirely self-financed and denies that it receives funding from Russia or serves Kremlin interests. “If we hold a protest in front of the US Embassy, they say we’re pro-Russian. And if we protest against Russia, as we have done numerous times, they say we’re pro-Islamic,” he said.

Bektour Iskender, co-founder of the Kloop.kg news site and one of the few prominent Kyrgyz defenders of LGBT rights, does not exclude the possibility of Russia funding Kyrgyz media outlets or groups like Kalys, but can’t prove it. However, he says it’s easy to understand why Kalys targeted Lukash; an energetic, young activist who dressed colorfully and conformed to few accepted standards, he was a convenient, largely defenseless scapegoat.

Lukash’s friend Olga Gein frames it another way: he was simply too passionate and committed to the causes he supported. She compares him to Danko, a character from a Maxim Gorky folk tale who tore out his own burning heart to light his people’s way through the dark woods.

“Ilya is an enthusiast and a dreamer. He can live a great idea. He doesn’t care about material things,” Gein said. “If he’s burning for something, he’s going to burn.”

Even so, such nuances mattered little to his harassers. On March 8—knowing he had nothing left to lose—Lukash organized one last pro-Ukraine rally against Russia’s annexation of Crimea, then left Kyrgyzstan the next day for Kyiv, a city where he knew almost no one.

“Because of frequent threats and pressure, I must leave Kyrgyzstan,” he wrote in a terse Facebook post shortly before his departure. “Sorry for all the unfulfilled plans and dreams, but losing the battle is not the same as losing the war. I will return to you all, and maybe soon.”

Starting over

Lukash’s first months in Ukraine were lonely. He longed for Kyrgyzstan and the sight of the Ala-Too Mountains on the horizon. But thanks to his extensive media and PR experience, Lukash found work almost immediately. Still, he felt unsatisfied.

So Lukash decided to take a risk. He quit his stable job and moved to Lviv in order to learn the Ukrainian language. It paid off. By the time he returned to Kyiv one month later, he had mastered conversational Ukrainian and was soon able to get a job at Znaj.ua, a Ukrainian-language news site. The new job fulfilled one of Lukash’s long-time dreams, becoming a journalist. But it was far from easy. The salary was meager at first, and initially, his articles were riddled with typographical and grammatical errors. Lukash nearly got fired, he recalls, but editor-in-chief Nadia Kotova let him stay because she saw that his written Ukrainian was improving. She was also impressed by what he’d been through.

“When I heard his story, I thought he would work well for our site because we are very pro-Ukrainian and support Ukrainian independence,” she said. “To us, he’s a normal person.”

Looking back, Lukash says he has no regrets. Sadly for him, nor do his enemies. Moldokmatov, who burned Lukash’s portrait, still insists the activist “repeatedly propagated homosexuality and wrote that he was organizing a Maidan in Kyrgyzstan” on his social media pages.

Moldokmatov claims he knows nothing about hackers posting that information to Facebook, and won’t discuss the subject because “it will make it easier for [Lukash] to get political asylum.”

He may be onto something there.

In February, the Ukrainian Migration Service denied Lukash asylum, despite the fact that the UN Refugee Agency recognizes him as a refugee. The decision disappointed Lukash but didn’t really surprise him. More painful, however, were headlines in the Kyrgyz press like “No One Needs Ilya Lukash in Ukraine” and “Even Ukraine Doesn’t Need a Turncoat.” In July, Lukash was denied asylum for a second time.

Now Lukash will appeal the decision even if it takes years, during which time he can remain in Ukraine. If that fails, he’ll have to use documents proving his Ukrainian ancestry to apply for citizenship. But he’d rather preserve his Kyrgyz citizenship for as long as possible.

“One day, if people like [pro-Western former Georgian President] Mikhail Saakashvili come to power in Kyrgyzstan and start liberal reforms, I will pack my bags and leave Kyiv quicker than when I left Bishkek,” Lukash said. “My country is still there.”

But that day seems far off. Last week, the Kyrgyz government tore up a cooperation agreement with Washington after the State Department recognized rights activist Azimjon Askarov, whom Amnesty International considers a prisoner of conscience. Later, Kyrgyz president Atambayev insinuated that the US government had been trying to create “chaos” and “ethnic instability” in Kyrgyzstan. And this fall, for a third time, the Kyrgyz Parliament will consider a bill that goes even beyond Russian law by mandating jail time for “gay propaganda.” If Parliament signs that measure—along with the “foreign agents” bill—and Atambayev signs them into law, Lukash may only be the first of many more political exiles.

Matthew Kupfer is a graduate student at Harvard University. He previously worked for the Washington-based Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Image: In March 2014, as Russia's “little green men” were quietly seizing the Crimean peninsula, Ilya Lukash fled Kyrgyzstan after Kyrgyz nationalists pilloried him as a “gay activist” during an anti-Western protest. Lukash had been an active, pro-Western civic activist in Kyrgyzstan, supporting the Euromaidan. Caught between fighting for his beliefs and Russia’s deteriorating ties with the West, Lukash chose to support Ukraine—the land of his ancestors—as it struggles for a European, democratic future. Credit: K-News screen grab.