Ukraine has suffered from a negligent and criminal administration, then revolution, war, invasion, annexation, and a situation close to economic collapse. One can argue that turning to legal solutions for recovery of some of the losses that Ukraine has suffered is not realistic or practical. While it is true that Ukraine cannot frogmarch members of the previous regime or Russian officials immediately into court and make them pay for Ukraine’s losses, there are legal processes with real-world consequences that are worthwhile to initiate. At a minimum, pressure can be brought through legal mechanisms to recover assets and encourage payment. In a recent paper for the Atlantic Council, I look at how Ukraine can potentially recover from the losses it has suffered from kleptocrats and Russia over the last few years.

Ukraine has suffered from a negligent and criminal administration, then revolution, war, invasion, annexation, and a situation close to economic collapse. One can argue that turning to legal solutions for recovery of some of the losses that Ukraine has suffered is not realistic or practical. While it is true that Ukraine cannot frogmarch members of the previous regime or Russian officials immediately into court and make them pay for Ukraine’s losses, there are legal processes with real-world consequences that are worthwhile to initiate. At a minimum, pressure can be brought through legal mechanisms to recover assets and encourage payment. In a recent paper for the Atlantic Council, I look at how Ukraine can potentially recover from the losses it has suffered from kleptocrats and Russia over the last few years.

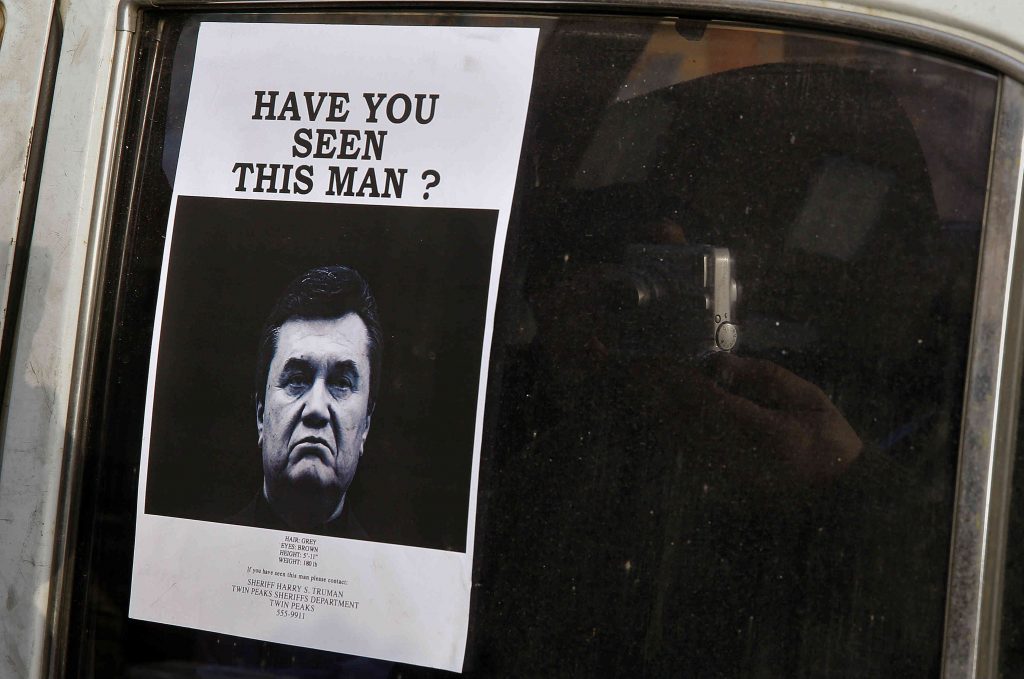

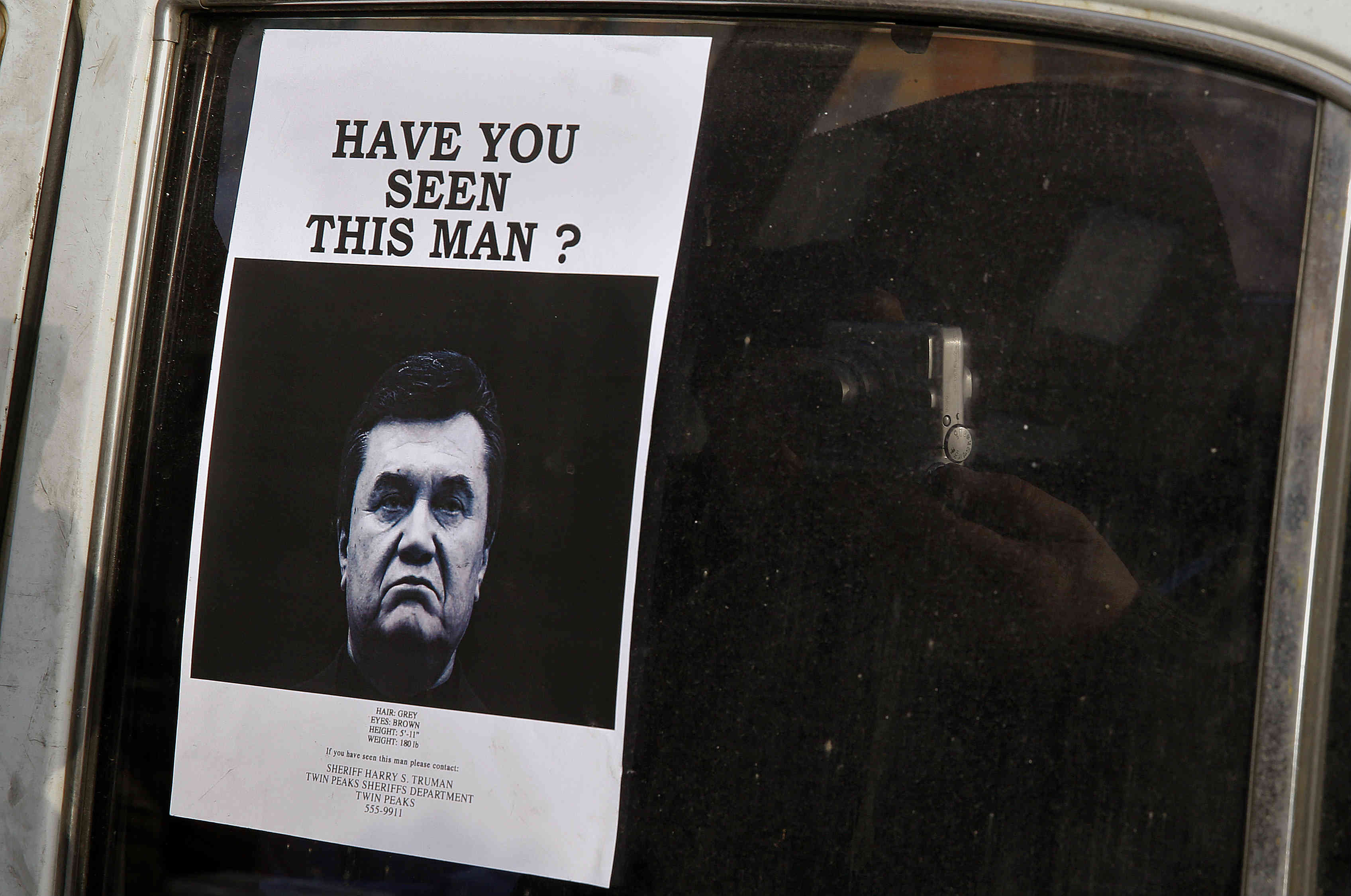

It is unclear how much senior officials stole during former President Viktor Yanukovych’s four years in office; however, the numbers are substantial. (I focus on VAT and public procurement fraud, as these tend to be more traceable in terms of how the fraud was committed and we can more easily put a number on the amount of much of potential plunder; for example, the annual procurement budget was approximately $12 billion.) Even taking a conservative estimate of the scale of fraud for just VAT and public procurement, one ends up with a figure of $30 billion. Of course, there were many other forms of state sponsored fraud.

At first sight, it looks difficult to do much about the stolen state assets and resources. The former officials are all beyond the reach of the Ukrainian courts, largely on Russian Federation territory, and few of the assets are in Ukraine.

However, the situation is not as bleak as it first appears. Because the officials of the former regime have little trust in the Russian legal system, most of their assets are located in Western or offshore-related Western jurisdictions. The location of those assets potentially provides significant leverage with which to bring about asset recovery.

One approach worth considering is deploying a plea bargaining procedure, and Georgia offers a precedent. In Georgia after the Rose Revolution, former officials were given a choice between criminal prosecution and returning stolen assets. Approximately $1 billion was recovered.

Ukraine’s legal system is much more heavily compromised than in Georgia after the Rose Revolution. It would be difficult to create an effective Ukrainian procedure which would permit such recoveries quickly. However, it may be possible to start with US (and possibly UK) procedures being deployed to assist Ukraine since many of the assets of former regime officials are held in Western jurisdictions. Western states, most notably the United States, may have jurisdiction where assets have been stolen or otherwise illegally obtained.

In plea bargaining procedures, the aim is to first create a credible threat. This would involve opening up criminal investigations against former officials; seeking red notices making it impossible for them to leave Russia and running in parallel a civil asset recovery operation. Having established a credible threat, then a credible offer would be made. That would involve dropping charges and giving former officials visa rights in the EU and the United States. In return, the former official would have to surrender at least 80 percent of the illegally obtained assets in his or her possession. For a former official living in Moscow wondering how long the Putin regime will survive, such a plea bargain may make good sense. While it is unpalatable that former officials are not held accountable, it may be better for Ukraine if the assets are substantially returned and can be used for the good of the Ukrainian people.

While plea bargaining procedures can work, relying on US procedures is not enough. At the very least, US officials will need Ukrainian cooperation in providing evidence of stolen assets. Another concern is whether Western states would be willing to help given the danger that returned assets will only be stolen again. The underlying problem is a Ukrainian one: the extent to which the Ukrainian political and bureaucratic class is still substantially controlled by individuals who continue to steal. This Ukrainian reality has to be faced if Western cooperation is going to be extended and be effective.

Turning to the losses from occupation by the Russian Federation, Ukraine should do two things. First, Ukraine should properly account for its losses. While Ukraine is unlikely to obtain recovery immediately, it is worth fully accounting for the losses of invasion and occupation, loss of life, property, destruction of businesses and infrastructure, and losses of internally displaced people. At some point, there will be a settlement. By establishing the losses that that Ukraine has suffered, Kyiv will have a number to negotiate with in future settlement negotiations. To underpin the credibility of the process, Ukraine should establish an international accounting board which will verify and certify the losses.

Second, Ukraine should focus on proceedings before the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) in Strasbourg. The European Convention on Human Rights gives Ukraine the means to account for its losses before an international tribunal. Furthermore, there is relevant and helpful case law as a result of a series of cases over the occupation of northern Cyprus.

Ukraine has already launched two cases before the ECHR, but the country should take a more strategic approach. As the international accounting process gets under way, it should launch a series of cases, including ones for internally displaced persons in the Donbas and small business owners in Crimea, and have a rolling series of cases. This approach allows cases to move speedily toward the ECHR, generates case law, and builds pressure for a settlement.

None of these solutions is immediate but it does build pressure on former officials and the Russian Federation and it moves Ukraine forward to a point that recovery becomes possible.

Alan Riley is a Nonresident Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Global Energy Center. This article is excerpted from a longer report published by the Atlantic Council in April 2016.

Image: A man takes photos of a "Wanted" notice, of fugitive former Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych, plastered on the window of a car used as barricade near Kyiv's Independence Square February 24, 2014. REUTERS/Yannis Behrakis