A Diaspora Russian Declares That 500 Pro-Kremlin Fighters Could Break Up Latvia

Latvia’s government and the world’s mainstream media may have been right to publicly ignore a Latvia-born Russian named Andrey Neronsky this week when he declared that “about 500 [Donbas-style] militiamen would be enough to end the existence of Latvia as a unified state.” Neronsky is a hardline and marginalized son of the ethnic Russian community in Latvia’s capital who has re-settled in Moscow to lobby there for greater support for the Russian diaspora in the Baltic states.

While there’s no evidence that Neronsky represents any significant constituency in either Riga or Moscow, his outburst, on a Russian website, did seize the attention of Latvian political analysts and officials, if only because Eastern Europe is a more dangerously unpredictable place since Russia’s seizure of Crimea and its proxy invasion of southeastern Ukraine. And it underscores that, even if Baltic governments handle well the local grievances of their Russian minorities, a deluded minority exists in the diaspora that the Kremlin can use as cover to press its neighboring states – psychologically or with real violence.

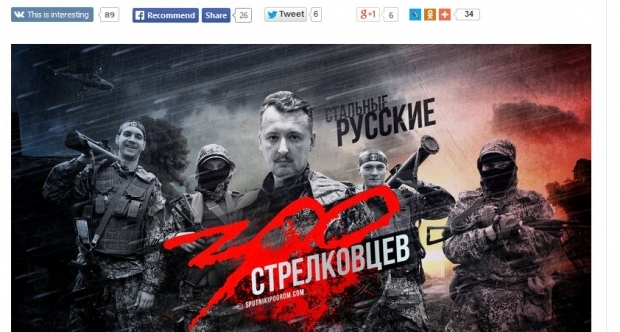

Kremlin-controlled news and cultural media have mythologized the gun-slinging Russian commandos of the Ukraine war (see the poster above), particularly the Muscovite army colonel who commands them. The lionization of Colonel Igor Girkin (or, as he calls himself, Strelkov, or “shooter”) has helped misguide diaspora Russians such as Neronsky to the conviction that commando assaults such as the war in Ukraine would be a good way to improve their lives.

Baltics’ Russian Minorities

“Discrimination against the Russian community [in Latvia] has increased in recent months [and] … the Russians’ patience is not limitless,” Neronsky said in the interview, on a Russian nationalist-inclined website, that brought him attention. The “example of the Crimea and Donbas could push them to take decisive action.” Latvia’s army and police are too weak to decisively defeat an urban guerrilla campaign by Kremlin-backed commandos, Neronsky says, and such an assault would seize territory in the two areas – Riga and southeastern Latvia – where Russians are most numerous. NATO, he suggests, would fail to intervene decisively, even though Latvia is a member state. And so “a repetition of the Ukrainian scenario is entirely likely in Latvia,” he says.

The Baltic states do face serious issues of how to manage the aspirations of their Russian-speaking minorities, who form about a third of the population in Latvia, a quarter in Estonia, and about 6 percent in Lithuania. Russians in the Baltic states were not automatically granted citizenship when those countries won independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. Many complain of “anti-Russian” government policies that favor the native Baltic languages to a degree that they say restricts their ability to get jobs.

But Neronsky, a fifty-year-old Riga-born businessman, is not a proven spokesman for Latvia’s Russian-speaking minority. After moving to Moscow years ago and founding what he calls the “Center for Russian Culture in Latvia,” he ran for the Riga city council last year on the ticket of the Zarya party, which won “precisely 774 votes (of more than 228,000),” wrote Riga-based journalist and journalism professor Karlis Streips. Even worse for him, voters used their right to cross Neronsky’s name off their ballots to indicate their disfavor, pushing him down from seventh on the party’s list to thirteenth among Zarya’s seventeen candidates, Streips noted in an e-mail. (In that election, Riga re-elected its first Russian-speaking mayor, Nils Usakovs, to a second term. The role in Riga and Latvia of Usakovs’ Harmony Center party reflects both a gradual political integration of Russian speakers in Latvia, and their continued demands for a better status for the Russian language and identity.)

Nersonsky’s outburst “served its purpose” as a piece of psychological warfare, said Veiko Spolitis, a counselor at Latvia’s Foreign Ministry. “Almost all Latvian Russian web-media outlets, and several Latvian-language ones used this,” and social media networks buzzed about it, he said by e-mail.

While a handful of Russians such as Neronsky may feel that liberation by Kremlin-backed militias would better their futures, independent news reports underscore the same phenomenon in the Baltic states as in Russian-speaking areas of eastern Ukraine: whatever the tensions over language and ethnicity issues, young Russian speakers increasingly consider themselves citizens of their non-Russian homelands. And in the Baltic states, they value the opportunities for careers, prosperity and travel that are offered by their countries’ membership in Europe.

From Reuters in a March 23 report: “Marija Kokareva, a twenty-something vendor at a market in the center of Daugavpils, is the face of a new generation that sees Latvia as its motherland. ‘I’ve spent my childhood in Latvia,’ she said in Russian. ‘I’m a Latvian citizen and would of course not want to separate from Latvia. We are proud of our country.’

James Rupert is an editor at the Atlantic Council.

Image: A Russian nationalist website offers downloads of a poster lionizing Russian Col. Igor Girkin and his militiamen fighting in Ukraine. It casts them as heroes from the 2007 Hollywood film "300", on the warriors of Sparta.