Ukrainians continue to “vote” with their feet by leaving, and the numbers are escalating due to pessimism at home and active recruitment by Europe.

Fresh polls register a devastating rejection by 71 percent of Ukrainians regarding the country’s political direction and even greater distaste for its leaders.

The 81 percent polled disapprove or somewhat disapprove of President Petro Poroshenko; 73 percent feel the same about Prime Minister Volodymyr Groisman; 88 percent feel the same way about parliament; and 77 percent feel that way about the judiciary.

Those polled, aged between 18 and 35, are even more disaffected. The poll also showed that less than one-third of Ukrainians under 35 will bother to vote in the next election and that only 20 percent believe they have a good future in Ukraine.

Political disaffection is not unique to Ukraine, but the lack of optimism and new access to European jobs foretells more migration.

When pollsters asked Ukrainians of all ages whether they believed younger people have a good future in the country, some 77 percent said no or somewhat no.

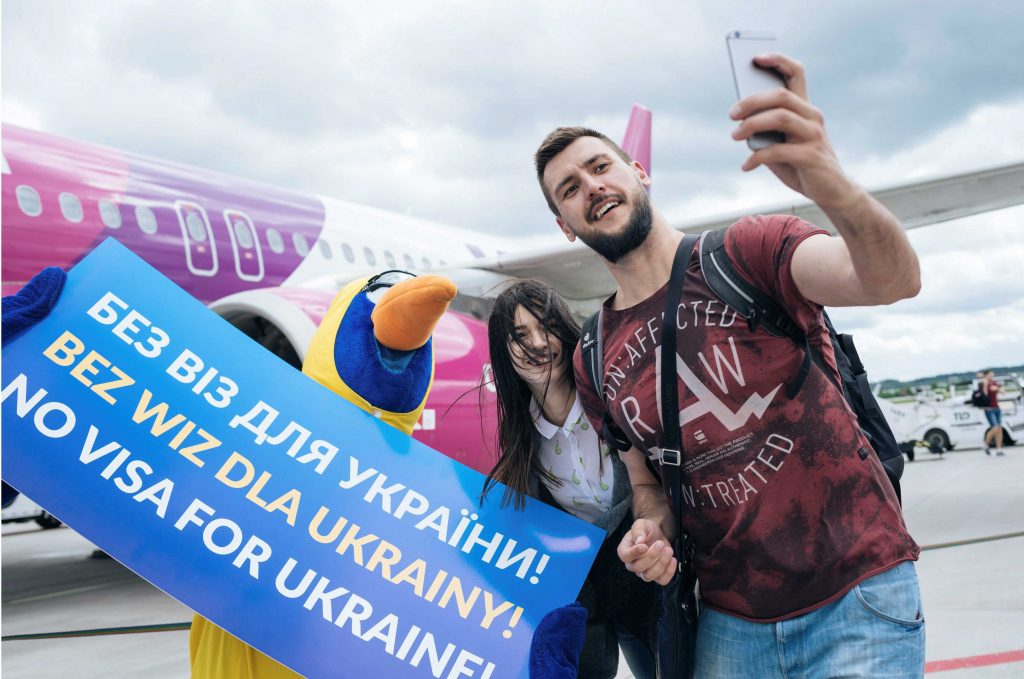

The exodus has increased after visa-free travel to the European Union was announced in July 2017. Since then, 17.6 million have crossed the EU border, according to Ukraine’s State Border Guard Service.

Stay updated

As the world watches the Russian invasion of Ukraine unfold, UkraineAlert delivers the best Atlantic Council expert insight and analysis on Ukraine twice a week directly to your inbox.

These short trips have provided an opportunity for more Ukrainians to hunt for jobs in Europe, to work illegally, to attend university there, and to connect with Ukrainian communities that can help them permanently relocate. This is nothing new, given the fact that Ukraine has already depopulated more than any other country in Europe.

Since independence in 1991, its population has fallen by 9.5 million to an estimated 44 million, nearly 18 percent, and the exodus of workers is the single biggest cause.

But the numbers grow. Poland, for instance, took in almost as many Ukrainians in 2016-17 as Germany took in Syrians. Other Eastern bloc countries are jumping into the search for Ukrainians because they need workers, want entrants who come from a compatible culture, and work hard. From the Baltics to the Balkans, governments are inviting Ukrainians to migrate.

The result is that one in six Ukrainians of working age now migrate to Europe to work, says a 2018 report by the Center for Economic Strategy. Many start as seasonal workers or short-term work permit holders then end up staying.

Between 2002 and 2017, 6.3 million Ukrainians permanently left, or more than 400,000 annually. This represents an enormous brain drain equivalent to the population of the city of Mariupol.

Then after the 2014 Revolution of Dignity and war with Russia numbers rose. Between 2015 and 2017 migration increased to 507,000 to Poland alone; 147,000 to Italy; 122,000 to Czech Republic; 23,000 to the United States; and 365,000 due to the war in the Donbas and Crimea to Russia or Belarus.

Historically, Ukrainian communities have thrived for decades in Canada and the United States as well as Brazil and Argentina. But more recent communities have sprung up in Europe: an estimated 300,000 Ukrainians in Italy, 45,000 in Portugal, 100,000 in Spain, and more than 2 million in Poland.

Ukraine’s depopulation is not unique in Europe. According to UN figures, the ten countries with the fastest-shrinking populations in the world are all former Eastern bloc nations, forecasted to sustain population drops of 15 percent by 2050. This widespread reduction in young workers in Europe is why Ukrainians are being sought. They are good workers, available on short notice, and earn the lowest average salaries in Europe.

“Our Ukrainian workers, the younger ones, are the best workers we have,” said an industrialist with a huge workforce engaged in the manufacturing and engineering tech and auto parts. “Others just cannot compare.”

Poland has relied the most on this influx as its aging workforce, and its own brain drain of workers to Western Europe, have created job openings. In the first quarter of 2018, Polish work permits to Ukrainians were up 40 percent for a total of 100,000 more than any quarter the year before.

Ukraine’s low birth rate is also another reason for its declining population. In 2016, for every birth there were 1.5 deaths. This is also the case in the other Eastern bloc countries.

Eurasia Center events

But Ukraine suffers more than most because the country is not secure, just, or economically vibrant. With the third most highly educated country in the world, its brain drain would be an issue even if the country got its act together, but now it’s devastating.

The cause is that corruption is pushing them out and Europe is pulling them in. And Ukrainians are smart enough to realize that if Europe is not coming to Ukraine anytime soon, then they must go to Europe.

Diane Francis is a Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Eurasia Center, Editor at Large with the National Post in Canada, a Distinguished Professor at Ryerson University’s Ted Rogers School of Management, and author of ten books.

The views expressed in UkraineAlert are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Atlantic Council, its staff, or its supporters.

The Eurasia Center’s mission is to enhance transatlantic cooperation in promoting stability, democratic values and prosperity in Eurasia, from Eastern Europe and Turkey in the West to the Caucasus, Russia and Central Asia in the East.

Follow us on social media

and support our work

Image: Passengers take a picture as they arrive from Kiev, after the European Union granted visa-free travel for Ukraine citizens at the airport in Gdansk, Poland June 13, 2017. Picture taken on June 13, 2017. Agencja Gazeta/Bartosz Banka via REUTERS