While serving as a senior official in the US intelligence community, I held posts directly responsible for the mission management and operational coordination of activities to counter our nation’s strategic threats. At the top of that list were the pervasive, multidimensional, and asymmetric challenges posed by the policies and actions of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

In 1999, two Chinese colonels penned the seminal military classic Un-Restricted Warfare, which argued for the intentional use of hybrid tactics. One of the authors, Colonel Qiao Liang, was quoted with the prescient statement: “The first rule of unrestricted warfare is that there are no rules, with nothing forbidden.” Yet, while China and Russia are testing such instruments in the gray zone, the United States has been hesitant to wield its own tools. It’s time for the United States to drop that reticence. It can start by using “lawfare,” or the intentional weaponizing of the US civil court system.

An American response

The United States has no shortage of zealous attorneys. It needs to unleash the lawyers so that they can help meet the country’s national security demands. The CCP engages in many malicious activities, from technology theft to unsavory investment practices to irresponsible behavior leading to the global spread of COVID-19. These kinds of abuses are ripe for US civil action.

Lawfare can help stem the rise of Chinese global influence by holding the CCP accountable in the court of world opinion while also helping to exhaust valuable time and resources that the party would need to spend defending its actions legally.

While the United States has not yet taken the CCP to court, China’s involvement in the opioid crisis provides a particularly relevant case to start with.

Is the CCP helping traffic fentanyl?

Opioids constitute a national crisis in the United States. The misuse of and addiction to opioids—including synthetic opioids such as fentanyl—are responsible for tens of thousands of deaths per year. While the crisis has been caused by the wanton overprescription of opioids to Americans for everyday ailments, it has been fueled by the supply of illegal fentanyl which has both increased its accessibility for addicts and profitability for dealers. Since 2013, China has been fueling this crisis, acting as the number one supplier of illegal fentanyl and the precursor chemicals of fentanyl to the United States. While China imposed regulations on fentanyl in 2019 that reduced direct shipment to the United States, fentanyl precursors continue to flow in via Mexico.

It’s unlikely that the CCP will acknowledge and therefore cease what appear to be the state-sanctioned abuses of its pharmaceutical industry, so the US and global court systems must step in to deliver justice.

To bring China to court, the United States must first make the case that the CCP is involved in driving the opioid crisis. The US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) has classified the precursor chemicals for fentanyl (which China supplies) as controlled substances, essentially making them illegal. In May, DEA Administrator Anne Milgram told CBS News: “We would like China to do more. For example, we need to be able to track every shipment of chemicals that’s coming out of those Chinese chemical companies and coming to Mexico. Right now, we can’t do that.”

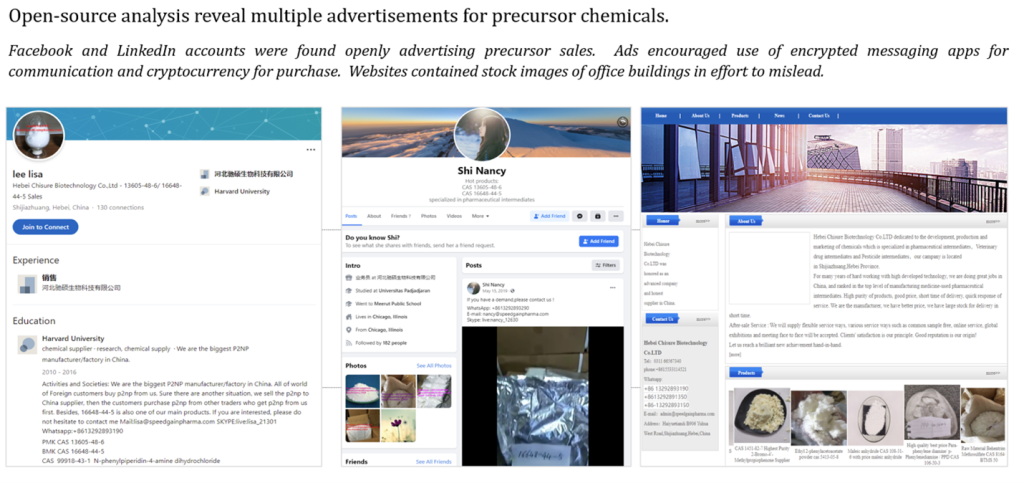

Given China’s restrictive, Orwellian business environment, companies illegally selling fentanyl precursors in the United States would likely be known to authorities. Some great open-source analysis conducted by J2X Solutions, a risk intelligence company, helps connect the dots. J2X Solutions identified thirty-seven Chinese companies as vendors of 4-Anilinopiperidine, a direct precursor to fentanyl. Five of the thirty-seven companies were identified as manufacturers of the precursor.

Further analysis noted that some of these companies’ use of social media networks like LinkedIn and Facebook meant they could exit “the great firewall of China”—which would require the tacit approval of government monitors—and hide in the crowd of busy platforms through the use of fake photos, profiles, and handles. (This research is not publicly available but was provided to me by J2X Solutions.)

The DEA has gone on record to state that it is “not aware of any legitimate uses of 4-Anilinopiperidine other than potentially in the synthesis of fentanyl.” That fact explains why these companies try to obfuscate their sales by using non-traditional marketing sites, façade accounts, Bitcoin transactions, and encrypted messaging apps.

A US court order

As Chinese companies hinder US national security through the illicit sale of fentanyl, the United States can leverage nonmilitary means to weaken the effectiveness of their activities. In addition to traditional law enforcement activities, the United States should empower US civil attorneys to file massive class action suits in both US and world courts.

The Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA) of 1976 provides a viable starting point. The act shields foreign states from suit for their sovereign, but not their commercial, activities, stating:

“Under international law, states are not immune from the jurisdiction of foreign courts insofar as their commercial activities are concerned, and their commercial property may be levied upon for the satisfaction of judgments rendered against them in connection with their commercial activities.”

The Chinese government’s control over the business environment—meaning fentanyl precursor sales to the United States are surely known to authorities—opens the floodgates for potential class-action suits from the tens of thousands of victims of wrongful deaths from Chinese-supplied fentanyl. When the chemicals are routed through Mexico, China could face additional liability under a FSIA provision that applies to commercial activity outside the United States that “causes a direct effect in the United States.”

One relatively easy way to broach this would be to diplomatically ask the Chinese government to halt these shipments from within their country. If China did actually assist, problem solved. In the more likely instance where Beijing would feign ignorance, this would then open the regime up legally under a concept known as “intentional indifference,” triggering potential civil liability under FSIA. While this might not be enough to make China stop its malign actions, it would induce shame, generate negative press globally, and force China to expend massive legal resources.

Colonel Qiao was not wrong when he stated there are no rules when it comes to warfare. The sooner the United States and its allies realize, accept, and adopt this mindset, the sooner they can intentionally employ asymmetric tools like lawfare. Proactively harnessing the robust US legal system—in conjunction with other actions below the threshold of armed conflict such as information campaigns and cyber acts—could help steer the behavior and response of adversaries like China.

Tom Ferguson was a member of the Atlantic Council’s Gray Zone Task Force before assuming a position in government.

Further reading

Fri, Jun 10, 2022

The future of US security depends on owning the ‘gray zone.’ Biden must get it right.

Hybrid Conflict Project By Clementine G. Starling-Daniels, Julia Siegel

The United States' ability to prevail in the gray zone will hinge on coordinating and executing a whole-of-nation response.

Mon, Apr 25, 2022

I helped defend against China’s economic hybrid war. Here’s how the US can respond.

New Atlanticist By

Washington must regain its strategic momentum relative to China and stem Beijing's global economic influence.

Wed, Feb 23, 2022

Today’s wars are fought in the ‘gray zone.’ Here’s everything you need to know about it.

Hybrid Conflict Project By

Our experts help illuminate this shadowy zone of strategic competition—and offer ways for Washington and its allies to begin seizing the advantage.

Image: Fentanyl, a dangerous synthetic opioid. Photo via Star Tribune/TNS/ABACAPRESS.COM via Reuters.