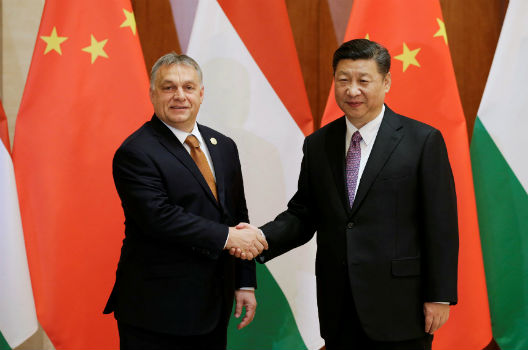

SCHLOSS ELMAU, GERMANY – Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban recently shared some history with a friend, explaining why he reached out to China’s then-Premier Wen Jiabao in 2011, seeking urgent financial support and providing Beijing one of several European inroads in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis.

Orban’s reason was a simple one: survival. Facing a potential debt crisis and unwilling to accept austere loan conditions from Western institutions, Beijing offered a lifeline. For his part, Orban convened some Central European leaders with Beijing, and they laid the groundwork for the “16-plus-one” initiative based in Budapest that since then has provided China unprecedented regional influence.

It didn’t take long for China’s investment to bear fruit. In March 2017, Hungary took the rare step to break European Union consensus on human rights violations, refusing to sign a joint letter denouncing the alleged torture of detained lawyers. In July 2016, Hungary joined Greece – another distressed European target of Chinese largesse – in blocking reference to Beijing in a Brussels statement on the illegality of Chinese claims in the South China Sea.

The Bavarian Alps might seem an unusual place to reflect on China’s growing global influence, in a week that began with U.S. President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping working to avoid a trade war in Argentina and advanced to Canadian authorities’ arrest of Chinese tech company Huawei’s CFO in Vancouver, at US request on suspicion of Iran sanctions violations.

Transatlantic strategy experts – convened at this breath-taking resort by the Munich Security Conference – were left to reflect on Europe’s unique vulnerability to this major power conflict in a world where they are absorbing the unanticipated shocks of greater US unpredictability, greater Chinese assertiveness and deeper European divisions about how to navigate it all.

“China already has shown it can have a veto power over European Union policy,” said Wolfgang Ischinger, chairman of the Munich Security Conference, on the margins of the off-record gathering he convened. He notes that while West European companies are driven by profit, their Chinese counterparts invariably also represent Chinese state interests. “That doesn’t have to be malign, but it can also be malign.”

European Union officials concede that China already has exercised the veto power it has over policies that require unanimity, and because some officials are pushing privately for a change to majority voting. Concerns are growing as Beijing’s influence has grown more rapidly than anyone anticipated. Chinese foreign direct investment in the EU has risen to $30 billion in 2017 from 700 million before 2008.

A report by two German think tanks, the GPPI and Mercator Institute for China Studies, found that Beijing has taken full advantage of Europe’s openness and has been “rapidly increasing political influencing efforts in Europe.”

Some call it political warfare, using a nonmilitary toolbox of overt and covert means to exert its influence on political and economic elites, academia and public opinion. With these efforts, it weakens Western unity (and US attraction) and improves its image as an alternative to liberal democracy, the report concluded.

Growing Sino-US tensions have brought Europe new export chances in China but at the same time China has shifted considerable export and foreign investment efforts to Europe to replace lost American markets. In the first six months of this year, newly announced Chinese mergers and acquisitions into Europe were nine-fold the North America number at $20 billion compared to $2.5 billion and completed investments were six times higher at $12 billion compare to $2 billion.

At the same time, a new Trump-Xi trade deal could shake Europe as well, as China’s state driven economy could decide overnight to replace European products with US goods for political purposes.

The potential for an escalated Beijing-US struggle has left European experts scratching their heads over how they would choose sides or navigate the perils, particularly in the case where some countries and industries have much more at stake in China.

Some European officials speak of the need for “strategic autonomy” in the face of US sanctions’ extraterritorial reach on Iran and Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s speech in Brussels this week where he questioned multilateralism and the European Union. At the same time, they worry more about what some call China’s “political warfare” of gathering economic, financial and thus also diplomatic influence.

The European Union hasn’t yet applied anything as restrictive on foreign investment as the US Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), an interagency committee that reviews the impact of foreign investments on US national security. However, the EU this month

passed a bill creating an unprecedented, if non-binding, screening scheme aimed at predatory Chinese investments.

Germans this week increased their focus on questions regarding a company called KUKA Robotics, which has become the poster child for the perils of high tech sales to the Chinese. With its industrial robotics production, KUKA was one of the nation’s greatest innovators for the 21st century economy until it was taken over by the Chinese company Midea in 2016.

Just last month, Midea was reversing previous assurances that it would not remove KUKA’s highly respected and long-time CEO, underscoring China’s ultimate control over cutting-edge robotics technology.

Despite facing new scrutiny, China is undeterred in its European strategy, taking advantage of European divisions, America’s trade strains with Europe and the urgent investment needs of particularly Southern and Eastern European countries.

Tellingly, President Xi made a stop in Spain on his way to Argentina and then again in Portugal for a two-day stint on his way back from the G-20 meeting, his first state visits to both countries.

Even before Xi’s visit, China had invested $12 billion in Portuguese projects ranging from energy, to transport, to insurance, financial services and media. During Xi’s visit, China and Portugal further deepened their economic partnership, with Lisbon agreeing to cooperate in China’s Belt and Road Initiative as it hopes to garner increased Chinese infrastructure and energy investments. China is also poised to take over a majority stake in EDP, Portugal’s largest business and a major EU energy provider.

In short, global markets and news reports miss the real story with their single-minded focus on whether or not President Trump and President Xi can reduce tensions and close a trade deal over the next 90 days. The bigger game, increasingly apparent in Europe, is whether China can replace the United States over time or at the very least significantly reduce its influence.

This article originally appeared on CNBC.com.

Frederick Kempe is president and chief executive officer of the Atlantic Council. You can follow him on Twitter @FredKempe. Subscribe to his weekly InflectionPoints newsletter.

Image: Chinese President Xi Jinping meets Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban ahead of the Belt and Road Forum in Beijing, China May 13, 2017. (REUTERS/Jason Lee)