Since taking power in August 2021, the Taliban has pursued a sustained assault on the rights and dignity of women by subverting the established legal order and creating a new order characterized by arbitrary and abusive exercise of executive, legislative, and judicial power.

So far, the Taliban has adopted more than two hundred decrees targeting women and girls. The bans and restrictions affect all aspects of life—from banning girls’ education past the seventh grade and limiting women’s employment to curtailing their freedom of movement and social engagement. To implement these decrees, Taliban authorities exercise broad discretionary powers to interpret and enforce the law, relying on a range of extrajudicial methods such as physical coercion, social control, and public intimidation.

In effect, the Taliban regime has employed the instruments of lawmaking and law enforcement to establish a system of control and oppression of women that amounts to gender apartheid. The system was reinforced with the adoption of the Propagation of Virtue and Prevention of Vice Law on August 21, 2024. While women’s rights and freedoms were already curtailed by earlier Taliban decrees, the adoption and implementation of this law has had far-reaching consequences, stripping women of even more basic rights and personal autonomy and exacerbating their economic dependence and social isolation.

To combat the Taliban’s institutionalization of gender apartheid in Afghanistan, international actors and civil society groups should document both the regime’s human rights abuses and the system of lawmaking and law enforcement that produces them. Documentation strategies should be geared toward supporting ongoing cases at international courts and catalyzing further accountability processes. An international investigative mechanism, modeled on the United Nations’ (UN) International, Impartial, and Independent Mechanism for Syria (IIIM), can help to hold the Taliban accountable for implementing gender apartheid and the specific rules and tools they use to maintain that system.

From constitutional order to rule by executive fiat

Prior to the Taliban takeover, the legitimacy and legality of the Afghan state were vested in the 2004 Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, which served as the supreme law of the country for seventeen years.

The Constitution was preceded by a Constitutional Loya Jirga or “grand council,” held in 2003, and was approved by consensus in January 2004. It provided an overarching legal framework for the relationship between the Afghan government and Afghan citizens and stipulated a set of constitutional principles and rights, such as separation of powers, due process of law, freedom from persecution, and freedom of expression.

In the new order created by the Taliban, by contrast, there is no constitution or equivalent supreme law. Laws and regulations are issued by the Taliban’s leader, Hibatullah Akhundzada, by his leadership council, and by a host of public officials and religious authorities in an ad hoc manner. Sometimes they take the form of written decrees, such as the “Virtue and Vice” law, but often they are only issued verbally. For example, officials from the Ministry for the Propagation of Virtue and Prevention of Vice set the law in declarations and conference speeches, while clerics do so in sermons—bypassing any formal process of lawmaking and ignoring basic requirements that laws must be general, prospective, clear, and stable.

Lawmaking and law enforcement as instruments of control and oppression

In the absence of a constitutional framework that anchors the legal order, regulates the exercise of state power, and protects the rights of citizens, Taliban law draws on a range of other sources. They include extremist religious ideology rooted in a rigid—and contested—interpretation of Sharia law, which has been influenced by the Deobandi school of thought, as well as patriarchal tribal norms and practices.

These sources inform and justify the system of control and oppression of women that has emerged and expanded under Taliban rule, which includes bans and restrictions on women’s education, employment, and a range of fundamental rights and freedoms. While the system is built on a multiplicity of verbal and written decrees and directives, the Taliban is aware that its effectiveness depends on more systematic codification and consolidation. This may explain the broad remit of the Propagation of Virtue and Prevention of Vice Law, which, inter alia:

- Bans women from travelling without a male guardian and denies them access to parks, gyms, and other public spaces.

- Requires women to cover their faces and bodies in public; for example, Article 13(8) stipulates: “If an adult woman leaves her home for an essential need, she must cover her voice, face, and body.”

- Declares that women’s voices are awrah (private), which means that women should not be heard in public.

The law’s sweeping, vague language gives the Taliban broad discretionary powers to interpret its provisions, creating ample space for abuses. Article 17, for example, requires media outlets to adhere to religious guidelines, prohibiting any content that may be deemed contrary to Sharia law, without clarifying what that means in practice. Taliban forces are tasked with ensuring compliance with the law—especially by women—and violations are punished with warnings, fines, flogging, and imprisonment. Article 17 gives them broad surveillance and enforcement powers: “Taliban forces are present in markets, streets, universities, offices, and public transportation to ensure that people, particularly women, comply with the imposed laws.”

Such provisions of the “Virtue and Vice” law have further strengthened the core characteristics of law enforcement under the Taliban. An array of authorities—Taliban officials and forces, imams, and other religious figures—are exercising broad discretionary powers to enforce a growing number of vaguely defined rules in arbitrary ways, free from due process constraints and safeguards such as judicial review. Any attempt to resist or circumvent the regime’s bans and restrictions is met with a brutal response, often involving punishment on the spot. Human rights groups have publicized several cases of female activists being detained, disappeared, or killed for protesting Taliban laws. They have documented cases of women getting arrested for secretly teaching young girls and have reported on women being flogged for minor infringements and entire families being ostracized or punished for resisting Taliban edicts. The “Virtue and Vice” law reinforced this brutal system of arbitrary law enforcement with new written edicts that Taliban authorities could use to justify human rights abuses.

Pushing back on gender apartheid: Documentation and accountability strategies

Afghan women are already living in a system of pervasive control and oppression that is best described as gender apartheid. Left unchecked, the Taliban will further institutionalize and entrench that system, making it even more difficult to challenge and reverse in the future. International actors—including international organizations, concerned states, human rights groups, and Afghans in the diaspora—must take appropriate steps to prevent that outcome.

Documentation and accountability strategies offer a path forward. Documenting human rights abuses is critical but given their widespread and systematic character, it must be complimented with documentation of Taliban lawmaking and law enforcement—the rules and practices that produce these abuses. And it must involve structural investigations to show how egregious abuses of power and human rights violations are not byproducts of the system of gender apartheid in Afghanistan but are rather its very means and ends, central to maintaining the system.

Building robust documentation can support ongoing accountability processes and initiatives, such as the case against the Taliban at the International Criminal Court for gender persecution as a crime against humanity. It can also strengthen an anticipated case at the International Court of Justice (ICJ). In January, Germany, the Netherlands, Australia, and Canada announced that they intend to sue the Taliban at the ICJ for gross violations of women’s rights, invoking the interjurisdictional clause of the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women.

The experiences of other countries affected by widespread and systematic repression and human rights abuses suggest that documentation efforts can open other, potentially unforeseen pathways to accountability—when such efforts are scaled up and institutionalized. Afghanistan needs an international investigative mechanism modeled on the IIIM for Syria. The Syrian IIIM was established by the UN General Assembly—bypassing the Security Council—and has contributed to a spike in universal jurisdiction prosecutions of Syrian offenders for war crimes and crimes against humanity.

An IIIM for Afghanistan can serve both as a catalyst and repository for gender apartheid documentation. It can also help build structural investigations and prepare criminal cases for prosecution when jurisdictions are able and willing to take up such cases in the future. This would create a vital resource and build momentum for the growing movement to criminalize gender apartheid in international law and ensure that its architects are held to account.

Wesna Saidy is a poet and researcher with a degree in law and political science, focusing on human rights and gender justice in Afghanistan. She is a fellow at the Civic Engagement Project focusing on documentation.

Iavor Rangelov, PhD, is a research fellow at the London School of Economics and has extensive experience with documentation, justice, and accountability strategies in the Balkans, Central Asia, East Africa, the Middle East and Latin America.

This article is part of the Inside the Taliban’s Gender Apartheid series, a joint project of the Civic Engagement Project and the Atlantic Council’s Strategic Litigation Project.

Further reading

Mon, Nov 25, 2024

A protester’s story from inside a Taliban prison

Inside the Taliban's gender apartheid By

Narges Sadat recounts the conditions she was forced to endure in a Taliban prison for protesting Afghanistan’s gender apartheid regime.

Tue, Sep 10, 2024

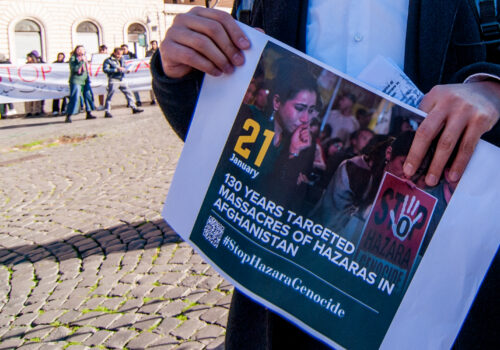

‘The death of Hazaras is permissible.’ What it’s like to protest the Taliban as a minority woman.

Inside the Taliban's gender apartheid By

Tamana Rezaei recounts the compounding dangers she faced as a woman and member of the Hazara minority protesting the Taliban’s rule.

Mon, Aug 26, 2024

The Taliban’s violence ‘ignited a fierce resistance within me.’ A protester’s story.

Inside the Taliban's gender apartheid By

Nayra Kohestani recounts the abuse and imprisonment she and her children suffered for resisting the Taliban’s gender apartheid regime.

Image: An Afghan woman and a girl walk in a street in Kabul, Afghanistan, November 9, 2022. REUTERS/Ali Khara.