On August 21, Afghanistan’s de facto authorities formally published a 114-page document detailing the vice and virtue laws governing the private lives of women and men, including bans against women’s voices being heard and faces being shown in public.

These new decrees come as Taliban rule reaches its three-year mark. After the Taliban seized control of Kabul in August of 2021, Nayra Kohestani took to the streets to demonstrate against rising gender apartheid in her country. For this, the Taliban subjected her and her young children to violence and imprisonment, a story she recounts below.

As a child, I was excited to go to school every morning. At university, I studied pedagogy to fulfill my dream of becoming a teacher. I wanted to give hope to a generation that had only experienced violence and degradation. I taught for twelve years, up until the very day Kabul was taken over by the Taliban.

Even as I watched city after city fall in the summer of 2021, I still went to school as usual on August 15. At 11:00 a.m., my spirit broke when we were told to dismiss our students because the Taliban had arrived in Kabul. My vision went black, and it felt like a hand had entered my body, squeezed my heart, and pulled my lungs and organs out through my throat. Deep despair filled me in a way that no words can describe.

At that moment, the past twenty years flashed before my eyes, and I was taken back to 1996 when I was a small child and the Taliban first entered Kabul and publicly hanged former President Mohammad Najibullah. My father, a government official, left for work that morning but fled for his hometown of Kapisa, where we later joined him.

The Taliban caught up with us in Kapisa. I remember the Taliban coming to our house, threatening to burn it down. The fighters then imprisoned and tortured my great-grandfather for several months to force a confession and find his sons. They returned and bombed our house, but thankfully the men and boys had already escaped.

Our village resisted the Taliban’s rule throughout the 1990s under Commander Ahmad Shah Massoud. But the Taliban ultimately captured our village and forcibly displaced its residents to Panjshir. Every time we tried to return to our village home, the fighters forced us back to Panjshir. I will never forget the stench of dead bodies that filled the fields and overwhelmed our senses whenever we returned to Kapisa.

In 2001, after the NATO intervention and the establishment of an interim government, schools once again opened, women returned to their work, public and private universities restarted, and stadiums became venues for sports once again. I was only nine years old at that time and had already missed three years of education. While excited to go back to school, fear still gripped my body. I worried whenever I heard knocking on the door, fearing that Taliban soldiers were coming to take away one of my family members. When I joined the badminton team and would practice at Ghazi Stadium, images of women stoned by the Taliban at that very stadium would haunt me. I would imagine Taliban whips on my mother’s legs until the sounds of children playing jolted me back to reality.

When the Taliban returned to power in 2021, the regime resumed its policy of gender apartheid with an onslaught of decrees affecting education, the right to work, the right to health. We were virtually prohibited from sightseeing or being present in society. And of course, our most private issue—the right to dress—was circumscribed. Taliban soldiers beat women on the streets, showing no mercy to children, young women, or the elderly. This systematic exclusion of women worsens daily as the Taliban comes up with ever more new ways to disappear women from society.

At first, fear consumed me, and I trembled at the mere sight of Taliban soldiers on the street, so I remained in the house for weeks. When Ahmad Massoud, the son of Ahmad Shah Massoud, called for a national uprising, I secretly prepared to take to the streets. But my husband stopped me, refusing to allow me to leave the house for days because he was abiding by the Taliban’s apartheid rules.

On October 11, 2021, I swallowed my fears and stepped out of the house and began to walk. I was whipped so badly by Taliban fighters that day that I fainted from my pain when I finally returned home. As I shivered with fever, my mother took off my clothes to apply ointment on the red welts that covered half my body.

But the violence I experienced that day ignited a fierce resistance within me. I vowed to fight for my daughter, Raha, and not let the suffering my mother and I experienced befall her too. I knew that the only hope of freedom lay in resistance. So I reached out to the girls posting photos of their protests and joined them. My family didn’t approve, so I remained secretly active.

That changed on December 16, 2021, when I decided to publicly take to the streets to raise my voice for freedom. My participation quickly made headlines, and the media widely circulated my picture. My family, angry at me, rejected me—leaving me entirely alone.

With nothing left to lose, I joined other women in escalating our protests, reaching out to media and confronting the heavily armed Taliban. We endured beatings, gunfire, pepper spray, and chemical substances. Some women were arrested, tortured, and even killed. Even so, our protests continued to grow.

In January 2022, after another protest, Taliban fighters followed us. While we managed to escape, the Taliban began finding and arresting a number of our fellow female protesters—one after the other. The rest of us moved continuously from one safe house to another. A month later, dozens of Taliban fighters attacked the safe house we were staying in. Armed with weapons, military rangers, and suicide squads, the Taliban arrested us. Faced with such overwhelming force, we realized then that our voices—our only weapon—were a significant threat to them.

In the dark and terrifying interrogation room, a Taliban soldier placed his Kalashnikov rifle against my temple and screamed at me, “Confess!” I refused and shouted back, although I was scared, and anticipated a gunshot to my temple. We spent five nights being insulted and humiliated. Neither we nor our children—my kids were age seven and three at the time—were given water, food, or medicine. They told us that our punishment would be stoning, but after five days, their behavior changed. They brought water and food to our cells and also provided a doctor and medicine.

I remained in a Taliban prison with my two children for fifteen days, in a room lit day and night and infested with rat droppings and insects. My children’s health deteriorated further each day, but on the sixteenth day, the soldiers told us they had received assurances from our relatives that we would stop protesting. But they confiscated our land and house titles and, I presume, made other threats to our relatives.

Today, after all this violence and cruelty, my heart is shattered by the world’s indifference to the plight of Afghanistan’s women and their situation under the Taliban. The international community not only failed to hold the Taliban accountable for its cruelty, its two rounds of oppressive rule, and its gender apartheid, but the United Nations even recently hosted Taliban officials in luxury in Doha while the regime brazenly continues to hold Afghanistan’s women hostage.

Nayra Kohestani is a teacher and the founder of Sun’s Girls organization who now lives outside Afghanistan. This article was edited from an interview with Kohestani by Mursal Sayas.

This article is part of the Inside the Taliban’s Gender Apartheid series, a joint project of the Civic Engagement Project and the Atlantic Council’s South Asia Center.

Further reading

Wed, Aug 14, 2024

I was imprisoned and tortured by the Taliban for protesting gender apartheid in Afghanistan

New Atlanticist By

Zholia Parsi describes protesting against gender apartheid in Afghanistan after the Taliban returned and abuse she faced as a result.

Tue, Apr 30, 2024

Don’t look away: The Taliban’s mistreatment of women has global ramifications

Inside the Taliban's gender apartheid By

The Taliban’s impunity for its violations of international human rights law poses grave risks to women’s rights worldwide.

Thu, Mar 21, 2024

Afghan women’s rights are not a lost cause. Here’s what the international community can do.

Inside the Taliban's gender apartheid By

The United Nations must prioritize Afghan women's rights in its policy agenda and avoid forms of engagement that could embolden the Taliban.

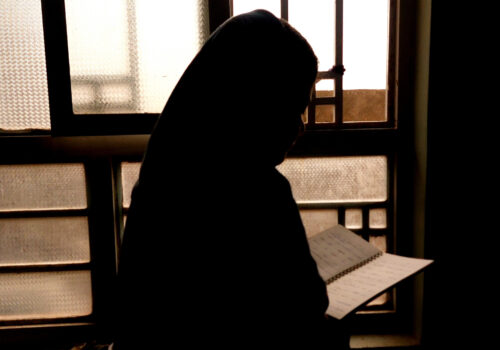

Image: Afghan women shout slogans during a rally to protest against the Taliban's restrictions on women, in Kabul, Afghanistan, December 28, 2021. REUTERS/Ali Khara.