A three-year trade policy marathon starts this week with the long-awaited confirmation of Katherine Tai to become the United States Trade Representative (USTR). The Biden-Harris administration has signaled an intention to hit the ground running with the March 2 release of the president’s 2021 Trade Policy Agenda alongside the 2020 Annual Report.

Advocates for “fair trade” and action on climate change will be pleased to see the strongest commitments to date from the United States government regarding their priorities. European policymakers will similarly welcome a broad range of policy alignments alongside a full commitment to cross-border partnership opportunities.

While many will celebrate the shift towards a values-based trade policy, the 2021 trade agenda also indicates that trade tensions (not to mention potential trade wars) loom on the horizon. It is not a secret that the Biden Administration will continue–if not increase–the trade policy pressures on China. The minor role assigned to digital and data policy issues from the 2021 trade agenda also implicitly signals subterranean trade tensions may yet create significant challenges for the transatlantic relationship.

Transatlantic Trade Policy Alignments

Environmental and labor rights were always going to play a large role in any Biden administration trade policy. Washington’s objectives and priorities align well with Europe’s trade policy priorities, which were published last month. Compare:

Specific commitments in both cases include mobilizing a broad array of regulatory policy tools to promote climate-friendly policy and market shifts. The new USTR policy also publicly commits the new administration in Washington to consider carbon border adjustment policy options. European policymakers have already promised to deploy such an adjustment within Europe in a manner that complies with existing international trade rules. Stay tuned.

The new United States trade policy also implicitly endorses the European Union’s promise to use enforcement mechanisms to compel compliance with environmental commitments incorporated into existing trade agreements. In recent years, new EU trade agreements have incorporated specific environmental commitments. Comparable commitments are not found among a long list of existing United States trade treaties. The Biden administration’s 2021 trade policy suggests strongly that those agreements will not be renegotiated. Instead, the Administration pledges to “work with allies as they develop their own approaches and act against trading partners that fail to meet their environmental obligations under existing trade agreements.”

Two Trade Tensions to Track During 2021

Diplomacy and a commitment to cross-border cooperation with allies does not signal, however, that global trade tensions will decrease during 2021. Both the United States and the European Union are now publicly promising to use trade policy to pressure China across a range of issues. Less appreciated, but no less important, are the policy issues where US and European trajectories are not aligned, such as data policy. These two issues – (1) attempts to change China behavior and (2) disagreement over data flows–seem likely to trigger trade conflicts, if not full trade wars, during 2021.

China

Strong transatlantic policy alignment regarding China sets us up for a year of persistent pressure aimed at achieving changes on a range of Chinese policies. This is familiar territory for most trade policy watchers. Perennial complaints include state subsidies, currency manipulation, and intellectual property theft.

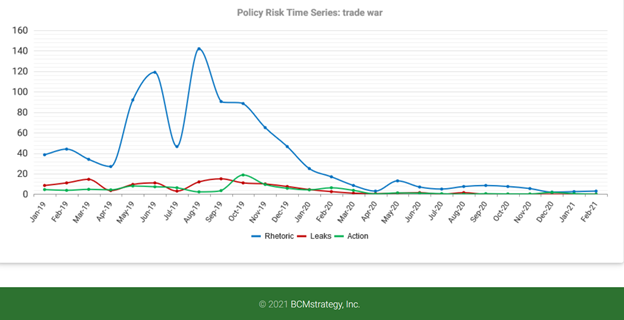

Of these, only the subsidies have generated the foundation for remedial action in the form of retaliatory tariffs by the Trump administration, which the Biden administration is likely to retain. The new US trade policy agenda signals a renewed effort to address possible currency manipulation: “The Biden Administration will examine how Treasury, Commerce, and USTR can work together to put effective pressure on countries that are intervening in the foreign exchange market to gain a trade advantage.” More recent complaints regarding Chinese human rights, forced labor, and genocide join climate policy on the list of policy issues being targeted for action through the trade channel. All signals thus point towards a significant increase in trade policy tensions once policymakers in Washington and Brussels start taking action. Compliments of COVID-19, aggregate global activity levels and concerns regarding trade wars nearly ceased during 2020, and most of the activity during 2019 was rhetorical. Policymakers talked about trade wars (often pointing out the dangers of undertaking trade wars) far more than they acted. When they did act by imposing tariffs or, at the start of the pandemic, by imposing export bans on personal protective equipment and pharmaceuticals, the reaction function was muted because policymakers had larger concerns.

2021 seems likely to revert back to 2019 activity levels as transatlantic leaders pivot towards pressuring China on the trade policy front.

The most consequential policy pivot starts with the strategic realization during 2020 that most of the world was dependent on China and India for a range of physical goods essential for survival (such as personal protective equipment, medical equipment, and pharmaceuticals) as well as raw materials essential for powering a modern, digital, and green economy (such as rare earth and other minerals). The race for creating supply chain diversification is now on.

The European Union styles the shift as delivering “strategic autonomy” which will be implemented first by “identifying strategic dependencies.” The United States styles the shift as delivering “supply chain resiliency.” Regardless of the moniker, the shift seems certain to escalate trade tensions with China. It also creates potential under-appreciated pressure points for the transatlantic relationship. A trade policy premised on supply chain diversification and resilience may start with China as its principal target, but it is far from clear that such policies will stop at Beijing’s door. Critical sourcing systems from COVID-19 vaccines to advanced technology will place pressure on existing economic relationships across the supply chain.

Data Flows

Despite the improved relationship between Washington and Brussels in 2021, divergences still exist, especially regarding trade and regulatory policy over the digital economy. The strongest area of disagreements arise with respect to data flows, where policy tensions tend to be expressed in terms of data privacy policy.

As the World Trade Organization’s 2020 World Trade Report indicated last year:

Data policies have become an integral part of innovation policies and a growing number of jurisdictions have passed new regulations to address data-related policy issues such as data privacy, consumer protection, and national security…Limitations on data flows or data localization policies often stem from privacy or security concerns, and therefore an effort to harmonize standards for data protection across countries or to develop mutual recognition criteria could build trust, and help prevent the spread of excessively restrictive data policies or a possible race to the bottom in privacy and security standards.

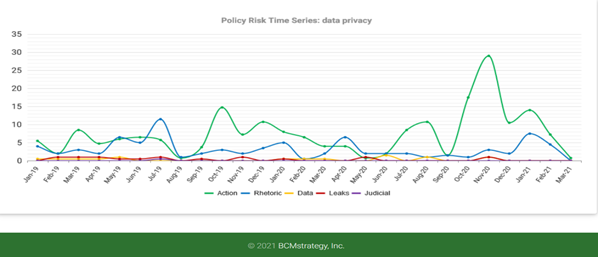

Despite the pandemic last year, a broad range of policymakers took action and signaled potential future action concerning data privacy policy:

The breadth of global activity that drove the spike in November 2020 illustrates well the challenge trade officials will have as they grapple with the post-pandemic digital transformation in the economy. Data privacy policy activity during 2020 included:

- central bank digital policy formation;

- alternative credit scoring;

- a substituted compliance application/framework between the Securities Exchange Commission and its German counterpart (BaFin);

- European Union efforts to enforce their data privacy standards against global corporations as well as UK banks (post-Brexit) with local European customers; and

- policymaker efforts to grapple with the data privacy implications of autonomous vehicles, smart appliances, and COVID-19 trading apps, and more.

Each sector of the economy will seek sectoral solutions. Pandemic-related acceleration towards a digital economy increases the importance of identifying workable standards promptly.

Policymakers in Brussels and Washington literally start from different points in 2021. The European Union has been expansive in articulating its strategic priority regarding the digital economy and data privacy:

The question of data will be essential for the EU’s future. With regard to cross-border data transfers and the prohibition of data localisation requirements, the Commission will follow an open but assertive approach, based on European values and interests…In particular, the EU will continue to address unjustified obstacles to data flows while preserving its regulatory autonomy in the area of data protection and privacy. To better assess the size and value of cross-border data flows the Commission will create a European analytical framework for measuring data flows.

These specific commitments do not find an analog in the Biden Administration’s recently released 2021 Trade Agenda. Instead, the digital trade policy agenda is relegated solely to the multilateral World Trade Organization discussions which have been lingering without material progress for nearly a decade:

The United States will work with Director-General Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala and like-minded trading partners to implement necessary reforms to the WTO’s substantive rules and procedures to address the challenges facing the global trading system, including growing inequality, digital transformation, and impediments to small business trade. The Biden Administration will also work with allies and like-minded trading partners to establish high-standard global rules to govern the digital economy, in line with our shared democratic values.

Transatlantic cooperation can accelerate the multilateral talks, if agreement exists on the underlying details. But existing US trade treaties create a blanket commitment to promote the free flow of data. Conflict on this issue with Europe, thus, seems inevitable.

With the issues of data privacy and trade relations with China likely to increase global trade tensions over the coming year, we should be careful about how we judge the balance of the transatlantic trade relationship. These tensions are real. The question is whether agreement on environmental, labor, and human rights policy priorities will be sufficient to smooth over what might otherwise be a very difficult divergence.

TradeWorld

Your guide to developments in international trade.

Image: Photo courtesy of the European Union