Cameroon’s future relies on empowering its women

Table of contents

Evolution of freedom

Indexes are only as good as the data they use and the methodology they follow. However, for Africa, indexes are an important determinant of how citizens perceive progress in the country, how bilateral donors make decisions on when, where, and how to extend support, and, lately, they are a fundamental component of rating agency assessments. As African countries seek to improve access to more affordable capital and crowd in more foreign direct investment, it is crucial that they pay attention to these indexes. Cameroon is no exception. In addition, indexes can provide rare insights into the linkages between issues such as environmental freedom and gender prosperity. The data on Cameroon suggest a strong link between economic freedom, health, education, and gender empowerment. This essay will focus on that and draw lessons for the future.

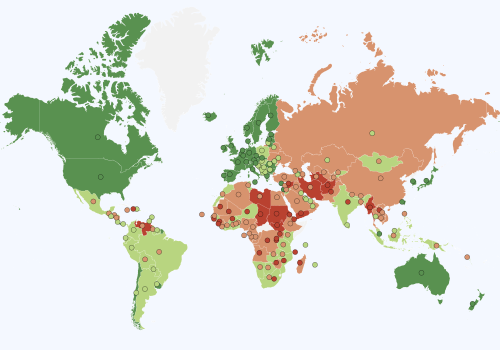

Cameroon’s score in the Freedom Index (47.6) is well below the average for the African continent (64.03) and many similar countries such as Senegal (68.7) and Côte d’Ivoire (61.7). The overall freedom measure is a composite score of the legal, political, and economic subindexes, where Cameroon ranks 133rd, 120th, and 144th respectively, out of 164 countries covered by the Indexes.

Cameroon’s poor performance in the Freedom Index since 1995 is mainly determined by the political and legal dimensions. The political subindex includes four main components: elections, political rights, civil liberties, and legislative constraints on the executive. Political power is centralized in Cameroon, unlike Senegal, for example, and as a result there is no effective system of separation of powers, with both legislative and judicial branches being dependent on the executive power. The level and trend of different components of the Index capture this general assessment.

The low levels of legislative constraints on the executive and judicial independence, compared to Côte d’Ivoire, for example, reflect the high level of concentration of power in the executive. The judiciary is subordinated to the Ministry of Justice, and the president is entitled to appoint judges (this is not unlike the United States but the degree of independence of the judiciary is also about implementation of policies) and only the president can request the Supreme Court to review the constitutionality of a law. Regarding the legislative, the formation of political parties has been permitted since 1997, and political rights are protected by law. Parliament is also highly dependent on the presidency, which appoints thirty out of the one hundred members of the Senate, the second legislative chamber established in 2013.

Strong executive power could and should actually benefit women’s economic freedom but currently does not. There are spillovers from the political subindex to other aspects of the institutional framework of Cameroon. This is visible in the economic subindex, which measures trade and investment openness, protection of property rights, and economic opportunities for women. Regarding the latter, Cameroon’s score in the women’s economic freedom component (60) is—surprisingly—among the lowest in the world, ranking 140th among the 164 countries covered by the Indexes. Despite a ten-point increase in 2018, reflecting the introduction of legislation dealing with workplace nondiscrimination and sexual harassment, Cameroon’s performance in this component is still significantly lower than that of other countries in the region, such as Côte d’Ivoire (95), Senegal (72.5), Nigeria (66.3), Gabon (95), and Kenya (83.8).

Important areas affecting gender equality, where Cameroon does not yet grant legal protection similar to the countries mentioned above, include civil liberties such as freedom of movement and marital rights, and financial inclusion legislation regarding access to banking services, asset ownership, and administration. While implementation of some of the more restrictive legislation may differ from the reality on the ground—for example, women can own property in their name today—the lack of changes to the legal documents opens the door for predatory compliance and legal battles in some cases.

Having women in government leadership positions has led many countries in the region to advance significant improvements in women’s rights and opportunities. One illustrative example is the case of Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala in Nigeria, who introduced several policies aimed at empowering women during her periods as finance minister (2003–06 and 2011–15), such as the Growing Girls and Women in Nigeria (G-WIN) program. This created a gender-responsive budgeting system that ensured a certain share of public procurement went to female entrepreneurs. Similar legislation can be identified in Kenya, with the Access to Government Procurement Opportunities program introduced in 2013, as well as in Côte d’Ivoire and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Adopting some of these tried and tested programs in Cameroon could help improve women’s economic freedom de jure and de facto.

Cameroon’s commitment to open and free trade is ambiguous, despite its very strategic location. Total trade to gross domestic product (GDP) has decreased substantially in the last decade, from 50 percent in 2014 to 39 percent in 2023, well below the average for Africa (74.49 percent). On the one hand, the country imposes relatively high tariffs on imports besides primary necessity goods, established at 10 percent for raw materials and equipment goods, 20 percent for intermediary and miscellaneous goods, and up to 30 percent for fast-moving consumer goods, implying an average tariff rate around 18 percent, more than double the average for Africa. With women being the most active small and medium entrepreneurs in cross-border trade, 20 percent tariffs have the potential to disproportionately affect them as a group.

On the other hand, Cameroon has signed trade agreements with the European Union, United States, China, Japan, and several other nations. In 2020, the country also ratified the African Continental Free Trade Area Agreement, the signature African trade agreement. Cameroon is also a member of the Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa, which aims a common market among Central African countries. Nonetheless, Cameroon has a negligible trade relationship with Chad, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, Central African Republic, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the other five member states. More generally, inter-Africa trade is still marginal, with only 12.7 percent of Cameroon’s export earnings coming from African partners, and less than 10 percent of total imports in 2023. For example, Cameroon’s trade with Nigeria—the largest economy in Africa—was less than 1 percent in 2021. The two countries having difficult and high tariffs undermines their collective prosperity. Policies to improve trade between the two countries will also disproportionately support small women-owned businesses.

The most relevant factor regarding investment and capital movement regulations in Cameroon is the fact that the national currency, the Central African CFA franc, is shared by the five neighbors mentioned above, and is pegged to the euro at a fixed exchange rate. This has the benefit of providing stability and predictability but also constrains Cameroon’s capacity to autonomously determine its monetary, investment, and capital flows policies. Another factor certainly influencing the investment climate in Cameroon is the security situation in the country and the region. With low tariffs in the sector, foreign capital continues to focus on extractive industries and infrastructure, and the repeated efforts of the government to expand international investment to other sectors have not borne the expected fruits.

Two other features of Cameroon’s institutional framework stand out in the legal subindex components, namely, the high levels of corruption across all levels of the administration, and the low level of security. Both of these unduly penalize women, who are generally the most affected by conflict and petty corruption.

Cameroon is host to a large number of refugees as a result of the conflict in the subregion, and this has impacted civil liberties. With respect to security, relatively high levels of small criminality have combined with a surge in terrorist attacks, especially in the last decade, with the emergence of Boko Haram and other Islamist groups, as well as the unrest in the north and southwest of the country. These different violent conflicts, together with the substantial immigration flows coming from Nigeria, Libya, Central African Republic, Chad, and other neighboring countries, have increased the need for tighter security within the country.

Evolution of prosperity

On the Prosperity Index, measured as the average of six constituent elements (income, inequality, minorities, health, environment and education), Cameroon performs better than its peers but still remains below the African average. The country has outpaced the low regional average in prosperity growth at least since 2005. Education, health, and environment seem to be the areas where improvements have been most palpable, and will be the focus of the following paragraphs.

The health component of the Prosperity Index, based on life expectancy data, shows a change of tendency around the late 1990s. This is not a feature unique to Cameroon; a similar inflection point from decreasing to rapidly increasing life expectancy is also observable in other African countries such as South Africa, Gabon, and Côte d’Ivoire. An important push in the fight against AIDS, substantially financed by programs led by the international donor community such as the US President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, was instrumental in this case. Additionally, the increased availability of vaccines for different diseases and some progress in terms of infant and maternal mortality have contributed to this positive evolution.

Nonetheless, there is still huge room for improvement. First, total public expenditure on health has been below 4 percent of GDP since 2001 (3.82 percent in 2021, the last year of available data), not yet close to the necessary level to ensure substantial and sustained betterment in health outcomes, usually estimated between 5 and 7 percent. For comparison, the average for Sub-Saharan Africa in 2021 is 5.1 percent, and for the Middle East and North Africa region reaches 5.76 percent. Similarly, health expenditure per capita in Cameroon was in 2021 just $155.56, substantially lower than in Nigeria ($220.40), Gabon ($411), or the average of the Sub-Saharan Africa region ($203.70).

Not only is aggregate spending relatively low, but also the destination of healthcare investment is not optimal. In the last decades, Cameroon has consolidated a series of big training hospitals, mainly located in big cities. On the contrary, investment in primary and preventive healthcare has been deficient, especially in rural areas, creating wide inequalities across the country. Recent disease outbreaks underscore the need for improved strong healthcare systems at the local level. As for other least developed countries, the potential gains of basic health interventions to ensure generalized access to vaccination and maternal and infant care are enormous, as the experience of other African countries has shown.

Turning to education, the data on school enrollment show a very significant acceleration since the early 2000s, when Cameroon started to grow faster than the regional average. It is important to note the very low initial level of this indicator, but the progress is still remarkable. Free primary education was introduced in the year 2000, and this is probably one important factor explaining the trend in the last two decades.

Nonetheless, families still need to cover the costs of uniforms and books, which is a significant barrier for an important share of the population. Recall that, according to the World Bank, 23 percent of Cameroon’s population is today living in extreme poverty (under US$2.15 a day), and thus such costs are very significant for them. Moreover, secondary school tuition and fees are not subsidized, which constrains educational attainment for a much larger fraction of children.

Two areas requiring substantial improvement are, first, the poor quality of the education received, which undermines actual learning outcomes of Cameroonian students. Learning poverty, the share of children not able to read and understand an age-appropriate text by age ten, is estimated by the World Bank at a high 71.9 percent, with girls especially disadvantaged.

Second, there are important sources of educational inequality, particularly gender and regional based. School enrollment rates are significantly lower for girls than for boys at all levels of the educational system, heavily influenced by high rates of child marriage and early childbearing among girls.

The attempt to impose French curricula across the whole country led to heated debate, protests, civil unrest, and ultimately, violent clashes in some parts of the country. As a result, schools closed for two years (2018–19), and before they had fully reopened, the COVID-19 pandemic hit and schools were closed again. This combination of shocks has probably generated a very significant slowdown in educational attainment that is not yet captured by the data used in the Prosperity Index.

Cameroon’s score on the environment component is heavily influenced by one of the variables used to compute it: access to clean cooking technologies. Although this indicator has improved consistently in the last twenty-five years, from barely 10 percent of the population to almost 30 percent today using clean technologies, once again we observe striking spatial differences across the country and between rural and urban populations. Cameroon produces gas and therefore could rapidly improve on this indicator. New cooking stoves are widely available and easily diffused. The executive has the power to improve on this indicator and save lives while improving livelihoods.

Most importantly, the Prosperity Index does not include any indicator on deforestation, which is extremely relevant for Cameroon, which has the second largest forest area in the Congo Basin, from which many women earn an income.

The evolution of tree cover areas reveals a loss of 1.53 million hectares between 2001 and 2020, of which 47 percent was in primary forests. As a result, forest as a percentage of land decreased from 47.6 percent in 1990 to 43.03 percent in 2020. In 2021, Cameroon was seventh on the list of the world’s top deforesters, with 89,000 hectares of forest lost. This trend not only threatens to significantly alter weather and crop patterns in the country, affecting women disproportionately, but may lead to deteriorating health conditions as nature and Cameroon’s biodiversity are altered significantly.

This situation is by no means unavoidable but requires a clear policy commitment if it is to be averted. Cameroon has important gas reserves, and the low usage of wood by households in cities proves that there are possible alternatives. Obviously, providing access to gas and other forms of energy to rural areas requires an important investment in infrastructure and creation of logistic networks that are not yet in place, but certainly should be a priority for the government and the international community in the near future. Cameroonian women not only suffer from a very unequal legislative environment, but also due to structural conditions on these areas that further hamper their personal development compared to men.

The path forward

The strength of data lies in its capacity to tell stories and be scrutinized. The data on Cameroon need more attention and the authorities should work with the groups that collect the original data used to build these Indexes, along with the Cameroon National Statistics Office, development institutions, and other research institutions that collect data, to ensure representation of Cameroon is accurate, especially since these data are often used by market players to inform investment decisions.

In the interim, one crucial conclusion from the data is the interdependence between the health, education, and environment components and the women’s economic freedom component. This interconnectedness is a double-edged sword, as weak legislative focus undermines women’s economic empowerment, which leads to poor health and education outcomes and in some cases may also lead to environmental degradation.

Bottom-up or top-down policies could help move these indicators, building on the successes already achieved in these domains, first by focusing on laws that provide women with better economic empowerment. This essay has cited several examples of initiatives in other countries which could be adapted to fit the national context and implemented in Cameroon.

Education remains the fastest way to economic empowerment of populations and women in general. In the long run it can help reduce costs of healthcare as educated women tend to adopt more preventive approaches for themselves and their children, reducing the cost of healthcare which is not only high but still comprises lots of risks for women. To this end, the policy of free primary education must be coupled with robust teacher quality and performance indicators to ensure that children are actively learning. A year of lost learning, even if it appears free, is costly for teacher, student, and parent. This kind of waste undermines the economy in the long run as an unskilled population is an economic cost to the country over time.

Cameroon’s environmental resources, if well managed, could represent an important source of revenue for local populations and women in particular in an economic environment where carbon markets are growing, protection of fauna and flora is valued, and organic production commands a premium from markets. Support by government to reforestation projects could help generate resources for rural populations while promoting more nature tourism, building on the strengths of the country. An important component of the women’s health and environment nexus, however, would be policies which help women use cleaner cooking practices, as unsafe technologies claim the lives of many women.

Overall, the policies needed to improve the economic freedom components for women are well within reach of the Cameroonian government, as many are policy-based first and foremost. In addition, it would serve the government well to work with the Indexes to scrutinize the data and scoring so that they can provide a more accurate report on the economic freedom of women in Cameroon.

Vera Songwe is a nonresident senior fellow in the Global Economy and Development practice at the Brookings Institution and chair and founder of the Board of the Liquidity and Sustainability Facility. Songwe is a board member of the Mo Ibrahim Foundation and previously served as undersecretary-general at the United Nations and executive secretary of the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. Songwe’s expertise includes work on Africa’s growth prospects in a global context, with a focus on improving access to sustainable finance.

Statement on Intellectual Independence

The Atlantic Council and its staff, fellows, and directors generate their own ideas and programming, consistent with the Council’s mission, their related body of work, and the independent records of the participating team members. The Council as an organization does not adopt or advocate positions on particular matters. The Council’s publications always represent the views of the author(s) rather than those of the institution.

Read the previous Edition

2024 Atlas: Freedom and Prosperity Around the World

Twenty leading economists and government officials from eighteen countries contributed to this comprehensive volume, which serves as a roadmap for navigating the complexities of contemporary governance.

Explore the data

About the center

The Freedom and Prosperity Center aims to increase the prosperity of the poor and marginalized in developing countries and to explore the nature of the relationship between freedom and prosperity in both developing and developed nations.

Stay connected

Image: Shutterstock

Keep up with the Freedom and Prosperity Center’s work on social media