Chile struggles with economic stagnation

Table of contents

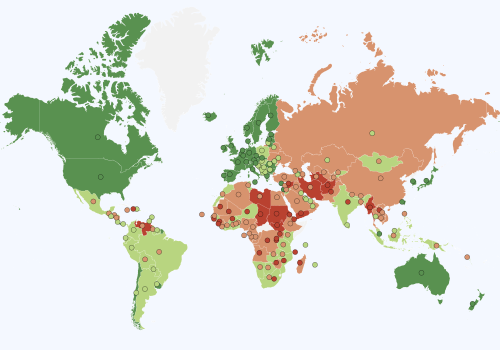

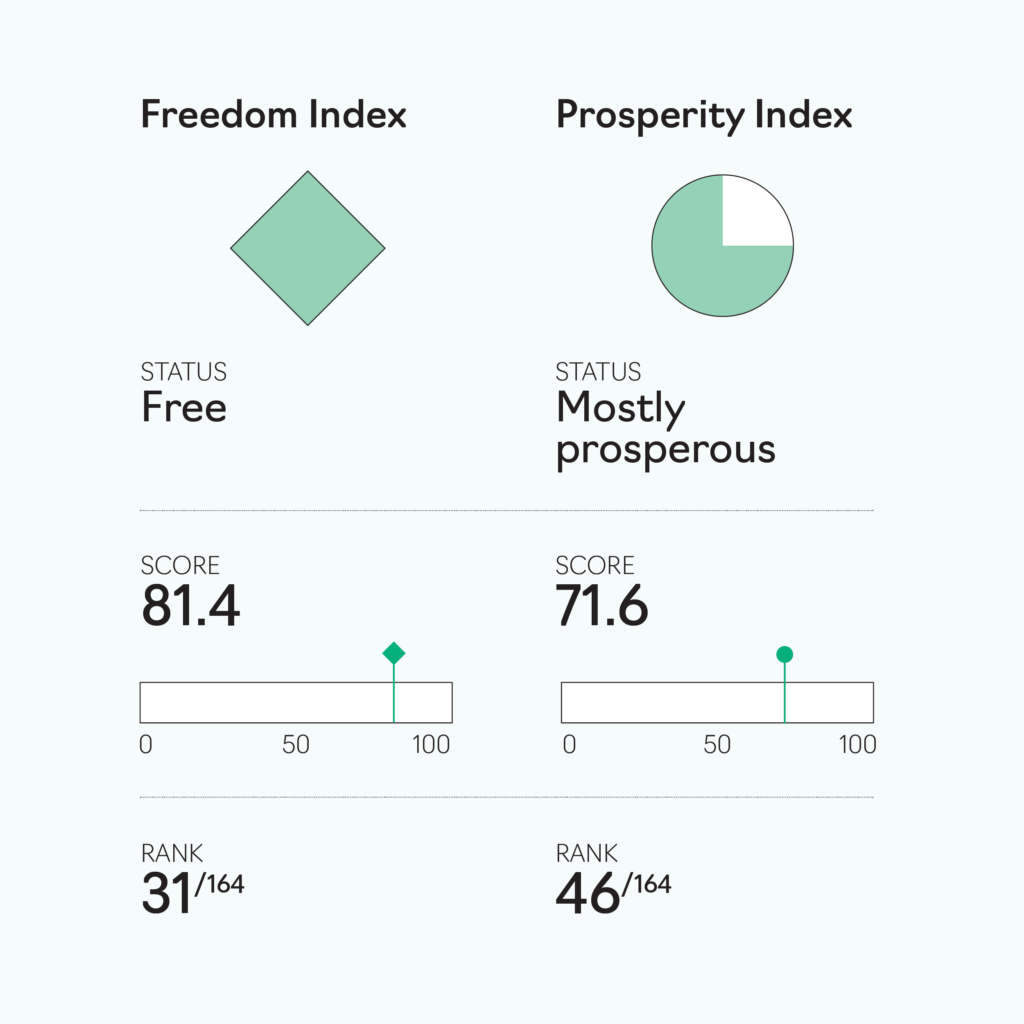

Evolution of freedom

The economic freedom subindex suggests that Chile is a country with open markets and a very open economy, but at the margin it has become less so over the last ten years. This decline has mostly been driven by policy decisions that increased government regulation of markets. Greater regulation was mostly welcome, but there may have been areas—like the length of time required to obtain approval for investment projects—where the trend has gone too far.

Most of the decline on the economic freedom subindex is attributable to changes in the trade freedom and investment freedom indicators. But the obvious measures of trade freedom, such as tariffs and nontariff barriers, have all been relatively flat or even improved over the last decade, and the last remaining capital controls were abolished fifteen years ago. Perhaps the explanation for this puzzle can be found in the property rights indicator, which has decreased in a mild but sustained fashion since 2010. Judicial procedures in Chile have become longer and more unpredictable, while processes related to obtaining permits have become maddeningly lengthy. As a result of these and other changes, the investment environment has deteriorated. Perhaps these measures partly explain the change in the trade and investment freedom indicators.

Regarding political freedom, the data presented seem like an inaccurate reflection of reality and are very hard to rationalize. Yes, Chile has become more politically fragmented and volatile, but civil liberties have not worsened. Perhaps a mild change in this subindex since 2019 could follow from the heavy-handed reaction to street unrest late that year, followed by the relatively stringent restrictions introduced in 2020 to fight the COVID-19 pandemic. But the data suggest a decline starting in 2015, which makes very little sense.

On legal freedom, the deterioration in the corruption indicator during the last fifteen years is attributable to a series of corruption scandals reported in the country. Here, as ever, it is hard to discern whether corrupt practices are now more prevalent or whether legal changes mean that more cases are being reported. Both could be true: It is possible that certain corrupt practices have indeed become more prevalent. But also keep in mind that the last decade-and-a-half has seen a number of changes in competition law and campaign finance regulations, which do make it easier to detect such practices.

In terms of security, it is clear that Chile has experienced a sustained deterioration regarding crime and safety on the streets. There is an active debate in Chile about the drivers of this trend. Some blame it on immigration, although there is limited evidence to support such a claim. Or, rather, immigration may have changed the nature of certain crimes (an increase in the use of firearms, for instance) but not the overall incidence of crime. Other factors, like a growing drug trade and the presence of foreign drug gangs, may also have had an impact. Whatever the cause, it is likely that security in large cities has worsened, even though Chile remains one of the best performers in the region when it comes to crime and citizen security.

From freedom to prosperity

Chile is a more prosperous nation than most others in the region. Its economy grew faster than most of its neighbors between the end of the last century and a decade ago. But recently growth has slowed. It is surprising that the data seem to show a larger decline in prosperity for Chile than for the rest of the region during the 2008–10 financial crisis, when Chile was undoubtedly the country with the smallest recession and experienced the most limited impact on economic activity in the whole of Latin America. This is, once again, a case in which the data presented make very little sense.

There is little doubt that Chile is an unequal country. But again, the data presented in this report tell a story that can scarcely be believed. The data suggest a sharp deterioration in income distribution, while the Gini coefficient computed by the government of Chile (and by the World Bank), shows a steady improvement since 1990, followed by a predictable deterioration during the pandemic and a slight recovery in the last two or three years. The inequality indicator of the Prosperity Index shows a completely different pattern. It may be due to the fact that the indicator measures the share of income of the top 10 percent of the distribution, which is a very partial view of income distribution.

The minority rights indicator has not shown much movement in recent years, though Chile’s score is reasonably high. However it is important to stress that this is largely because the indicator uses religious liberty as a proxy, whereas the real conflict in Chile is not religious but ethnic. If one had some measure of the situation of indigenous minorities, especially that of Mapuches in the south of Chile, the picture might look different.

Regarding the environment, Chile has a serious air pollution problem, both in big cities and smaller ones, but for different reasons. In the former, the number of cars per capita has increased substantially, and the move away from coal in the generation of electricity has been slow. In the smaller cities in the south of the country, by contrast, wood-burning stoves are the principal method of domestic heating. This is very polluting, especially if the wood is not fully dry.

There have been several educational reforms in Chile in the last twenty-five years, some more successful than others, but it seems unlikely that any of these could explain the complete stagnation in years of schooling in the 2007–11 period. There was a reform at the time that generated a movement of pupils among different types of schools, but not a decrease in enrollment. Moreover, spending per student increased significantly around this time, and the share of each cohort going to university reached the 50 percent mark in this period.

The future ahead

Chile faces two big challenges in the coming years, one economic and one political. The big economic challenge is to restore growth, which has slowed substantially in the last decade. Productivity growth, which was very fast late in the twentieth century and in the beginning of this century, has also petered out. Investment rates have not dropped, but nor have they increased. Chile was once a country experiencing rapid diversification of exports, and that process has also come to a halt.

So, when it comes to prosperity, the big question is: Why was the fast growth period in Chile so short-lived? Standard economic theory predicts that, as a country becomes richer, its growth slows due to convergence with high-income economies. So one might have expected fast growth in Chile until the country’s standards of living had reached the level of South Korea. Instead, fast growth seems to have stopped with the country still short of the income level of Greece or Portugal.

The big political challenge relates to the quality of politics and of democratic decisionmaking. Since 2010 politics has become more polarized and a great deal more fragmented. Chile went from having seven parties represented in Congress at that time to twenty-two today. Indices of satisfaction with the performance of democracy—and also indices of trust in government, political parties, the judiciary, the police, the media, business lobbies, unions, and so on—have all deteriorated. It seems that Chileans do not trust anyone anymore. That is a worldwide trend, but in Chile it might be a little more pronounced than elsewhere.

Chile’s answer has been to try to rewrite the Constitution. We have already tried twice, and failed, and the third attempt is also looking like a failure. Former president Michelle Bachelet drafted a new constitution in her second term (2014–18), but ran out of time to get it approved. A constitutional convention, dominated by the far left, was chosen in 2021, and wrote a questionable text that was rejected by 62 percent of voters in a referendum in 2022. A new convention was then elected, this time controlled by the far right, which produced a similarly partisan text that is similarly failing to attract widespread support. Polls suggest that the text will be again rejected by voters when it is put to a referendum in December 2023.

Andrés Velasco is a former finance minister of Chile, and a current professor of Public Policy and dean of the School of Public Policy at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

EXPLORE THE DATA

Image: Members of different Chilean groups perform during the Cultural Carnival in Valparaiso city, about 75 miles (120 km) northwest of Santiago, January 24, 2010. Valparaiso celebrates the beginning of the year of Chile's bicentenary with art activities in public places. Chile celebrates 200 years of independence on September 18, 2010. REUTERS/Eliseo Fernandez (CHILE - Tags: ANNIVERSARY SOCIETY)