Peru’s economy needs to unlock its green potential

Table of contents

Evolution of freedom

In order to adequately assess Peru’s performance in the Freedom and Prosperity Indexes, it is important to note the extremely difficult situation in the country during the late 1980s and early 1990s, immediately before the period covered by the Indexes. The extreme episode of hyperinflation that began in 1988 and peaked in 1990, with an annual inflation rate above 7,000 percent, and the intensification of the internal violent conflict generated by the Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso), a Maoist guerrilla group, are two examples of the challenges Peru faced in the decade before 1995. The Freedom Index coverage begins in the middle of Alberto Fujimori’s presidency, once most of his economic reforms were already in place, and when some of his authoritarian tendencies were evident. Thus, the economic subindex score in 1995 is relatively high compared to the regional average, while the political subindex is significantly lower, thirty points below the mean for Latin America. The return to free elections in 2001 is reflected in the large jump in the political subindex in that year.

Before discussing the Freedom Index evolution, it must be noted that many of its constituent components reflect the country’s written laws, not their actual implementation and enforcement. The potential gap between the situation de jure versus de facto is a typical issue with many indexes that try to assess politico-institutional variables, and it is often more pronounced in emerging and developing countries. This is crucial because we should expect institutional reforms to produce significant effects on prosperity only when they are effectively implemented. Peru is probably one of the clearest examples of this difficulty, with a set of written laws and regulations comparable to the most advanced countries of the world, but a level of implementation and enforcement that is far from such standards. Therefore, the picture portrayed by the Freedom Index may be too generous, especially in components such as women’s economic freedom and judicial independence and effectiveness. With this important caution in mind, it is possible to analyze the Peruvian experience as captured by the three different freedom subindexes.

The economic subindex level and trend since 1995 are explained by two main factors. First, Peru’s relatively high score compared to the regional average at the beginning of the period is the product of the large body of economic reforms implemented in the 1990s, in particular in terms of trade and f inancial openness. In the last thirty years, Peru has had very low tariffs on imports, including no tariffs on capital goods, and has entered into a number of free trade agreements worldwide. Moreover, it has imposed very limited restrictions on capital movement within and across borders. From a purely de jure perspective, capital account openness in Peru is comparable to the most open countries of the world. The Chinn-Ito index of financial openness has assigned the highest possible score to Peru since 1997, and the Fraser Institute’s Economic Freedom of the World Index gives the country a perfect score in its financial openness sub-area since the year 2000. However, Peru loses points due to the regulatory uncertainty and bureaucratic burdens that create constraints on investors, especially foreign investors; these barriers are considered in the investment freedom component. Reflecting a large increase in regulatory uncertainty during the election period of 2006, the investment freedom score abruptly fell twenty points, recovering in subsequent years as investors’ fears of strong government intervention in private sector affairs ultimately did not materialize.

Second, the overall positive trend since 1995, with a total increase of more than ten points in the 1995–2023 period, is to a great extent driven by the thirty-point improvement in the component measuring women’s economic opportunities. This is a good example of the legislation–practice gap. It would be hard to find a specific legal norm that includes any form of discriminatory treatment based on gender, especially in economic matters. But the actual situation is not so optimistic. Think for example about the so-called “child penalty,” the impact in terms of labor outcomes when a worker has a child. Forty-one percent of women in Peru quit their jobs when becoming mothers, while men barely see any change in their labor force participation. Moreover, recent research shows that only 51 percent of working age women participate in the labor market, and there is also a 25 percent pay gap with men.

The property rights component remains at very low levels. This is largely explained by significant problems with land titling, bureaucratic inefficiencies, and corruption in the judicial system; all of which translate into significant constraints for safeguarding and formalizing property ownership. The lack of clarity on property rights regarding land ownership disincentivizes investment and severely limits the ability of small enterprises, particularly in rural areas, to access credit, as land cannot be used as collateral for loans.

My impression regarding economic reforms in Peru is that, since the late 1990s, progress has been slow and limited. The various administrations since 2000 have not managed to implement a new wave of comprehensive structural reforms that could serve as an engine of sustained growth. There have been reforms, but they have been partial or hindered by significant implementation challenges. Fortunately, sound macroeconomic policies have been maintained in the last two decades providing economic and financial stability. But while macroeconomic stability is certainly necessary, it is not sufficient to drive sustainable growth. The period of Peru’s highest economic growth, from 2004 to 2014, was clearly facilitated by the global commodity boom, as the country is a significant producer of copper and other raw materials. However, when external growth engines slowed, the inaction of several governments in implementing essential economic structural reforms left the country without the much-needed internal drivers for sustained growth.

Turning now to the political side, I am skeptical about the very favorable assessment of the political system illustrated by the political subindex and its four components. Although declining in recent years, Peru’s political subindex is at a similar level to the average of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, scoring around ninety out of one hundred since the end of Fujimori’s presidency. This does not capture the actual functioning of the Peruvian political system, which is far from that of well-established liberal democracies in Europe and North America, or even the most advanced countries of Latin America such as Chile or Costa Rica.

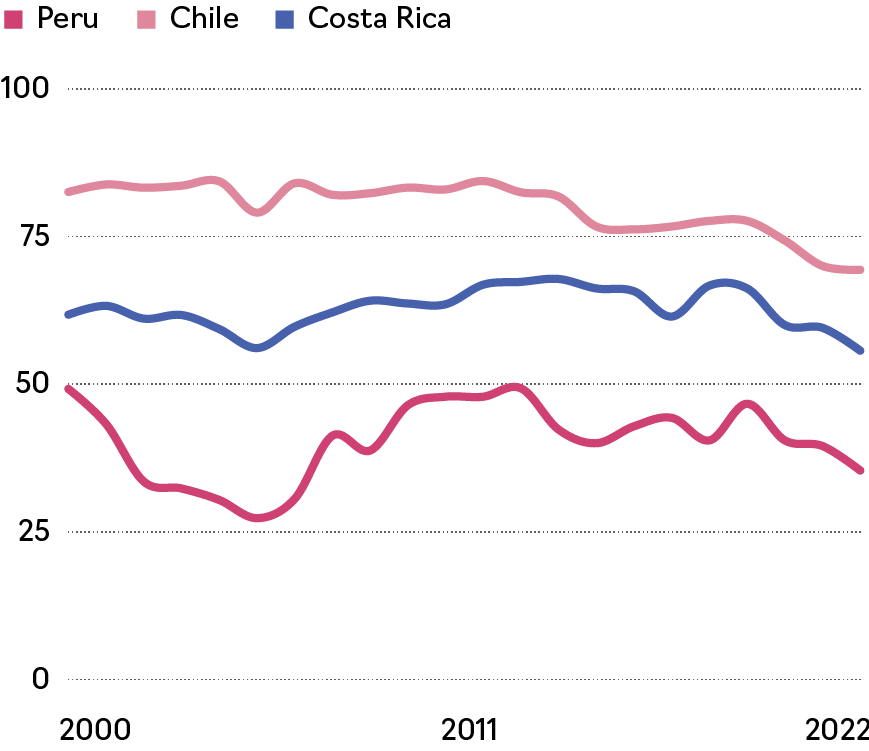

Figure 1. Rule of law

Figure 2. Government effectiveness

Source: Freedom and Prosperity Indexes, Atlantic Council (2024).

One of the most evident recent political problems in Peru is the lack of a deep-rooted party system. With few well-established political parties, the political spectrum is plagued with small and not very institutionalized political parties that appear and disappear in every electoral cycle, whose leaders often lack political experience and are prone to populist rhetoric and tactics. This political fragmentation is making it extremely hard for any government to pass substantial legislation or implement its policy agenda. A good example of the extremely dysfunctional political environment is the evident weaponization of the Constitution during the last decade, regarding the respective powers of the presidency and parliament. The Constitution enables Congress to denounce the president as incompetent and remove him from office, and also grants the president the power to dissolve Congress, under certain circumstances. Although this system was intended to create a balance between the legislative and executive branches, it has been used recklessly since 2016, leading to Peru having six different presidents in eight years, with only one of them staying in power for more than two years. To some extent, these developments are reflected in the decline in the legislative constraints on the executive component.

The general citizenry is very aware of the political situation of the country. Public opinion is strongly negative toward politicians and political parties. Recent waves of the Latinobarometer opinion survey clearly show that Peruvians are among the populations that have least confidence in the potential economic and development benefits of a free political system. This is worrying; once citizens become skeptical about the capacity of democratic institutions to deliver for all, the road to populism and authoritarianism is paved.

In the legal subindex, the judicial independence and effectiveness component faces the same criticism. The sharp rise in this component’s score, along with the improvement in the clarity of the law component, drive the clear discontinuity observed in the year 2000, which virtually closes the gap with the rest of the region. In the last twenty years, the legal subindex score for Peru has been relatively close to that of neighboring countries such as Colombia, and the gap with respect to the top performers in the region is moderate. However, I have doubts about whether this captures the real situation regarding enforcement of the law. A comparison with the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicator’s (WGI) rule of law measure can be enlightening here, as the latter captures to a much greater extent the actual enforcement of the law. Figure 1 compares Peru to Chile and Costa Rica. The difference between Peru and Costa Rica is substantial, with Costa Rica’s score around twice Peru’s for all years since 2000. The gap with Chile is even wider. Figure 2 shows a similar picture when looking at another related variable of the WGI, namely government effectiveness. That is, when using a measure of actual practice and enforcement of the law, Peru falls considerably behind the top scorers of the region, not to mention developed countries in Europe or North America.

Finally, the prevalence of informal labor and production relations in Peru is among the highest in the region, with some estimates reaching close to 70 percent of the total labor force. The World Bank estimates that the share of gross domestic product (GDP) contributed by informal production is around 50 to 70 percent higher in Peru than Mexico or Colombia, which are by no means the region’s best performers in Evolution of Prosperity this metric. The improvement captured in the informality component from the early 2000s is most likely a by-product of the commodity boom, a period of high economic growth that benefited employment and workers’ formalization, although some labor market reforms also supported this outcome. Nonetheless, informality is still a pressing issue for Peru, and a strong constraint on the future development of the country.

Evolution of prosperity

The poor quality and effectiveness of Peruvian institutions stand in sharp contrast to the relatively stable macroeconomic situation in the country, and the favorable perception of Peru’s economic performance and prospects among the international community. This is a paradox, as similar levels of political instability have produced very volatile macroeconomic environments in other emerging market economies, plagued with sudden stops in financial f lows, high levels of inflation, and default episodes. Many commentators attribute Peru’s macroeconomic stability to the deep scars the hyperinflation of 1988–90 left among the population and the political elites. The dramatic consequences of this event, with empty stores, lack of basic goods and services, and a rapidly impoverished middle class, are very much embedded in the citizens’ minds, and avoiding its repetition has been an absolute priority for all subsequent governments.

This fear has generated an implicit consensus, and politicians across the ideological spectrum have left management of the macroeconomic situation out of the political debate. The functioning of the Central Reserve Bank of Peru is the paradigmatic case of this arrangement, as illustrated by the fact that the Bank’s chairman has held this position since 2006, under eight different presidents. As a consequence, Peru’s macroeconomic performance in the last twenty-five years has been truly impressive, with a very credible commitment to a low inflation target, low levels of public debt to GDP (around 33 percent in 2023) and controlled government deficits, which granted the country’s public debt the investment grade in 2007.

The evolution of the Prosperity Index reflects this situation, showing an increase of almost fifteen points in the 1995–2019 period, eliminating the gap with the rest of the region. The income component largely follows the same pattern as the overall index. Nonetheless, a careful analysis of this trend reveals an evident slowdown of economic growth, especially since the end of the commodity boom. In my view, this stagnation is the direct consequence of a combination of weak institutional quality and a f lawed political environment. As a result, it is likely to persist unless a new and comprehensive reform process is undertaken.

The inequality component shows an impressive improvement in the last two decades, but it is important to take into account the really low level of this indicator in the early 2000s. The commodity boom undoubtedly helped reduce income inequality by pulling large numbers of workers into the formal sector and expanding the middle class. Although poverty- and inequality-reducing policies are in place across the country, and have played a role in supporting reductions in inequality, the limited capacity of many sub-national governments often means inefficient implementation and inadequate provision and quality of public services. As a result, regional inequality is a pressing problem in Peru. For example, according to a recent report by the World Bank, although more than half of urban households have access to piped water, sanitation, electricity and the internet, only 6 percent of rural households have access to these four services. Regional inequalities are also seen. For instance, residents in Loreto, a region in the Amazon, have eight hours a day of water access, in comparison with the country average of almost eighteen hours. There is extensive research showing that regional inequality is a serious issue, and some regions are noticeably being left behind.

I am somewhat critical of the education component, which is based on measurements of “quantity” of education, such as the expected and mean years of schooling, but does not take “quality” into account. The period of rapid growth enabled an increase in the government’s education budget, resulting in a significant rise in the percentage of children completing elementary, primary, and secondary education. However, while there have been advances, the quality of education remains a serious concern. For example, Peru was in the lowest quartile of the PISA global rankings. In the most recent PISA results, almost no students in Peru were top performers in mathematics, and only 34 percent attained at least a basic level of proficiency in mathematics, significantly less than the average across OECD countries (69 percent).1PISA is the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment. It measures 15-year-olds’ ability to use their reading, mathematics, and science knowledge and skills to meet real-life challenges.An educational reform introduced in 2012, building on the reform of 2007, aimed to improve teacher quality and student learning outcomes. A key goal was to transition from a system that allows hiring and promotion of teachers based on political connections to one based on merit. A major obstacle, however, has been political. The teachers’ union protested against elements of the reform, such as evaluations that could lead to job losses for underperforming teachers. The insufficient educational quality in Peru is a major constraint on long-term growth, as it limits the accumulation of human capital, essential for sustained economic progress. Many graduates lack the skills necessary to succeed in the labor market and are limited to low-paying jobs in the informal sector.

There is also a lack of quality measures in the health component. In particular, the indicator does not capture the large deficiencies in health infrastructure and the resulting shortcomings in patient care. For instance, studies conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic revealed that more than half of the establishments offering primary healthcare lacked a single doctor and were staffed only by nurses or technicians. The pandemic exposed serious deficiencies with the healthcare system, with devastating consequences. Peru reported the highest number of deaths per million inhabitants globally. Unsurprisingly, the country’s health score fell twice as much as the average for the region.

The very significant improvement in the environment component is almost exclusively driven by one of the variables used in its construction, namely the share of the population with access to clean cooking technologies, which has increased from 40 percent to more than 85 percent in the 2000–20 period. This is certainly good news, but there is still significant room for improvement in both indoor and outdoor air quality, as well as other environmental challenges. Examples of environmental challenges include illegal mining, especially in the Madre de Dios region, which leads to deforestation, mercury contamination and loss of biodiversity. Water contamination from untreated sewage and industrial waste is another major issue and there is a lack of effective waste disposal in many cities, contributing to plastic pollution, especially in urban areas along the coast. In addition, Peru is highly vulnerable to natural disasters exacerbated by climate change, such as extreme weather events and rising sea levels that affect the coastal area and fishing.

As reflected in the relatively low score assigned to the minorities component, protection against discrimination based on gender, race, sexual orientation, and other characteristics is relatively weak in Peru, falling significantly below the regional The Path Forward average, with the gap widening in recent years. Although there have been improvements, cultural and social norms continue to limit advances on this front. Another pressing issue is gender-based violence. A recent World Bank report highlights that the institutions responsible for protecting women and girls, including the police, the judiciary, and health providers, do not effectively protect them from abuse. Consequently, there is widespread mistrust among women toward government institutions in Peru.

The path forward

Peru’s prospects for prosperity are at a critical juncture. The previous discussion highlights that deficiencies in the capacity of the state to deliver public goods and services, including ensuring security and enforcement of the law, significantly constrain the country’s potential for regaining economic growth and overall prosperity. The weakness of institutions and governance, reflected in excessive bureaucracy, corruption, and a weak and inefficient judiciary, hampers domestic and foreign private sector investment. While maintaining a stable macroeconomic framework is key, it is not sufficient to provide the certainty and security investors need for long-term and productive investments.

A major challenge in implementing state reforms is political fragmentation, which prevents reaching consensus. Currently, ten political parties are represented in Congress and the number of parties may rise in the lead-up to the April 2026 presidential elections. This fragmentation is partially explained by weak legal requirements for forming political parties, which allow small groups to establish a party. The decline of traditional World Bank, Rising Strong: Peru Poverty and Equity Assessment. parties, such as Alianza Popular Revolucionaria Americana, and Acción Popular, has left a vacuum. This decline is another reflection of the population’s mistrust in institutions, which fuels the rise of new political movements, often led by charismatic but inexperienced leaders seeking to capitalize on widespread discontent.

How can much-needed pro-growth and inclusive structural reforms occur in this fragmented context? Fortunately, there is a promising opportunity for Peru in the coming decade: the green transition. Peru is rich in copper, lithium and other natural resources that are essential for clean energy technologies, which can position it as a crucial partner for the rest of the world. Additionally, its diverse geography provides significant renewable energy potential, especially in hydropower, solar and wind, which can reduce dependence on fossil fuels, create jobs, attract foreign investment, and improve energy security.

I am hopeful that recognizing the potential benefits of a comprehensive green transition strategy—such as growth, poverty reduction and equity improvements—can catalyze consensus even in a fragmented and polarized political climate. The increasing global push for environmental initiatives, along with efforts in other Latin American countries, could incentivize policy actions in Peru. If even partial consensus around this agenda is achieved, three areas of reform must be prioritized.

First, major investments in infrastructure and other projects are necessary to support the green transition. Improving the public sector’s capacity to execute these projects requires a systematic effort to build the technical capacity of subnational governments. This includes providing technical assistance and facilitating the hiring of trained personnel, including from abroad. Ideally, a comprehensive reform of subnational governments would involve consolidation of local and even regional governments, as some are currently too small to function efficiently. Yet while this reform needs to remain a long-term goal to improve efficiency, in the short term, in the context of high political polarization, this type of proposal could be weaponized, further increasing resistance to reform.

Second, to develop value chains related to the green transition—such as green manufacturing, renewable energy and eco-tourism—it is essential to facilitate the formalization of firms and workers. This requires significant labor market reform. Liliana Rojas-Suarez Currently, the very high costs of hiring, firing, and non-wage labor costs, above the region’s average, reduce incentives for firms to hire workers and for small and medium-sized firms to formalize. A more f lexible labor market would allow Peru to compete globally in emerging industries linked to the green transition.

Third, human capital development is crucial. The workforce needs to be equipped with the necessary technical skills to meet the demands of the green transition. Given the pace of technological change, workers must not only be prepared for current jobs but also possess the ability to adapt and learn. That means that serious improvements in the education and health systems are necessary. This will require sustained efforts across multiple government administrations to bear fruit.

Notwithstanding, if political consensus is achieved around the goal of advancing Peru’s role in the green transition, there is hope that political parties can form a common front to improve the quality of Peru’s future labor force. Sustained prosperity will then follow.

Liliana Rojas-Suarez is the director of the Latin American Initiative and a senior fellow at the Center for Global Development. Rojas-Suarez also serves as president of the Latin American Committee on Macroeconomic and Financial Issues. Rojas-Suarez has held senior roles in the private sector and at multilateral organizations, including Deutsche Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the Inter-American Development Bank. In 2022, Forbes named her one of the fifty most influential women in Peru.

Statement on Intellectual Independence

The Atlantic Council and its staff, fellows, and directors generate their own ideas and programming, consistent with the Council’s mission, their related body of work, and the independent records of the participating team members. The Council as an organization does not adopt or advocate positions on particular matters. The Council’s publications always represent the views of the author(s) rather than those of the institution.

Read the previous Edition

2024 Atlas: Freedom and Prosperity Around the World

Twenty leading economists and government officials from eighteen countries contributed to this comprehensive volume, which serves as a roadmap for navigating the complexities of contemporary governance.

Explore the data

About the center

The Freedom and Prosperity Center aims to increase the prosperity of the poor and marginalized in developing countries and to explore the nature of the relationship between freedom and prosperity in both developing and developed nations.

Stay connected

Image: Photo by Janaya Dasiuk on Unsplash

Keep up with the Freedom and Prosperity Center’s work on social media