Central America Economic Reactivation in a COVID-19 World: Finding Sustainable Opportunities in Uncertain Times

Key Points

- Central America has the opportunity to implement transformative structural reforms in the course of a post-pandemic recovery, if leaders in the region coordinate and invest in human capital.

- The private sector and civil society must play a critical role in anti-corruption efforts and new workforce and on-the-job training programs that align with business demands.

- The international community must support intraregional connectivity and deepen foreign investment partnerships in Central America, in addition to providing financial and technical assistance for pandemic response.

By: María Eugenia Brizuela de Ávila, Laura Chinchilla Miranda, María Fernanda Bozmoski, and Domingo Sadurní

Contributing authors: Enrique Bolaños and Salvador Paiz

Foreword

As the coronavirus pandemic rages on, countries around the world face an unprecedented test: concurrent public health and economic crises coupled with the resulting political and social reverberations. In Central America, the collective test of survival is no different—at least on its surface. But, as a region plagued by weak institutions, migration, violence, and lack of economic opportunities, Central America has to not only meet this unprecedented moment, but leapfrog beyond it.

COVID-19 is shining a spotlight on historic challenges and inequalities now accentuated by pandemic fallout. But, can the policy response to this public health and economic emergency also accelerate long-needed transformations in Central America? It must. Actions taken by countries today in response to COVID-19 will set the national development trajectory for perhaps the next decade. Bold, new actions and public-private cooperation can help to avoid another “lost decade.”1“Alicia Bárcena Calls for Implementing Universal, Redistributive and Solidarity-Based Policies to Avoid Another Lost Decade,” Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, April 2, 2020, https://www.cepal.org/en/news/alicia-barcena-calls-implementing-universal-redistributive-and-solidarity-based-policies-avoid.

Consider two pre-pandemic variables in Central America: a highly favorable demographic trend that will continue to churn out a large and young labor force in the next decade, and advances toward greater regional economic integration. When the pandemic hit, a third external variable came into the mix: in an ever-disrupted global economy, companies in China are seeking to relocate supply chains closer to the US market. As free-trade partners of the United States, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama have a unique opportunity to capture production and prominent roles in reconfigured global supply chains.

That is only possible through swift action to strengthen historically weak public institutions—long a roadblock to inclusive growth. Also, the rule of law must become the norm, not the exception. A 2017 Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center binational and bipartisan task force outlined a policy blueprint as to how Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador—in partnership with the United States—could improve the rule of law, provide sustainable economic opportunities, and address insecurity. While many task-force policy recommendations have been implemented, a renewed push is urgently needed to revisit other policy prescriptions that have yet to be addressed, but are fundamental for long-term recovery.

Since its founding, the Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center has advanced a different narrative on Central America—a narrative that does not see its entrenched problems as intractable. Rather, the Center promotes sustained, long-term, and multidimensional thinking that counts on the buy-in and collaboration of both the public and private sectors to help set a new direction for the region. This is not easy, but is necessary to set the region on a more prosperous path.

For all its ills, this publication argues that COVID-19, if addressed correctly, could be the catalyst to inspire long-needed policy reforms. The following pages highlight specific opportunities for Central America’s economic recovery at a time of increasing global uncertainty. Once travel opens up again, the Center looks forward to working hand in hand with Central American friends to advance the ideas presented in this paper; until then, it will work virtually to turn ideas into action.

Jason Marczak

Director, Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center

Atlantic Council

Introduction

When the coronavirus pandemic began to rattle developed nations in the West, experts warned it was only a matter of time before the virus reached emerging economies. By mid-September 2020, Latin America and the Caribbean—a region that accounts for only eight percent of the world’s population— reported more than a third of global COVID-19 deaths.2“WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard by the World Health Organization,” accessed September 23, 2020, https://covid19.who.int/?gclid=EAIaIQobChMIzLfU9d3C6gIVhJ-zCh2wng1jEAAYASAAEgJvGPD_BwE. As Latin American countries begin to ease lockdown restrictions—even as the number of new infections continues to rise in some countries—a grim outlook remains for public health, fiscal solvency, and economic growth and stability. In 2020, the combination of a stalled informal economy, a drop in tourism, capital flight, and climate disruptions will cause the region’s largest-ever economic contraction, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).3“A Joint Response for Latin America and the Caribbean to Counter the COVID-19 Crisis,” International Monetary Fund, June 24, 2020, https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2020/06/24/sp062420-a-joint-response-for-latin-america-and-the-caribbean-to-counter-the-covid-19-crisis. More worrisome, the United Nations World Food Program estimates that “severe food insecurity” in the region will quadruple, from 3.4 million to 13.7 million, during 2020.4Austin Horn, “14 Million People in Latin America, Caribbean at Risk of Hunger, U.N. Report Says,” NPR, May 28, 2020, https://www.npr.org/sections/coronavirus-live-updates/2020/05/28/864076929/14-million-people-in-latin-america-caribbean-at-risk-of-hunger-u-n-report-says. Perhaps one of the few silver linings is that remittance flows, after falling drastically in April, have since increased compared to 2019 despite the economic crisis.5Luis Noe-Bustamante, “Amid COVID-19, Remittances to Some Latin American Nations Fell Sharply in April, Then Rebounded,” Pew Research Center, August 31, 2020, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/08/31/amid-covid-19-remittances-to-some-latin-american-nations-fell-sharply-in-april-then-rebounded/. If Latin America is to successfully recover from this unprecedented crisis, leaders from across all sectors must work together to rethink how to shape a sustainable recovery that weaves short-term solutions with long-term strategies. Central America is uniquely positioned to be an integral part of a robust and sustainable recovery.

With a combined population of forty-nine million, Central America reported an average of 8,202 coronavirus cases per million residents in August 2020, compared to the global average of 3,500.6“COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science at Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University,” accessed September 9, 2020, https://gisanddata.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6. As seen across Latin America, Central American countries—with the notorious exception of Nicaragua—have implemented a combination of measures to respond to the pandemic, including lockdowns and curfews, additional funding and equipment for public health services, direct payments to individuals and families, and stimulus packages for small and medium-sized businesses, all with varying degrees of success.7Maria Fernanda Perez Arguello and Isabel Kennon, Nicaragua’s Response to COVID-19 Endangers Not Only Its Own People, but Also Its Neighbors, Atlantic Council, May 7, 2020, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/nicaraguas-response-to-covid-19-endangers-not-only-its-own-people-but-also-its-neighbors/. While the risk of a second wave of infections is still high as the region begins partial or full reopenings of economic activity (with a patchwork of health protocols implemented in different countries), leaders are faced with a challenge that can very well determine the prosperity of their nations: how to sustain reactivation of their economies in a COVID-19 world, especially given the preexisting institutional vulnerabilities that have hindered inclusive growth for too long?

“…leaders [across Central America] are faced with a challenge that can very well determine the prosperity of their nations: how to sustain reactivation of their economies in a COVID-19 world, especially given the preexisting institutional vulnerabilities that have hindered inclusive growth for too long?”

Amid a global crisis forcing countries and private enterprise to recalibrate how they do business and how they cooperate on issues of common interest, this unprecedented moment calls for national and regional action on how Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Panama can seize existing opportunities and find new ones to generate economic reactivation while addressing citizens’ pressing health issues. The Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center of the Atlantic Council has identified three key areas of opportunity: a demographic bonus of a large working-age population; nearshoring of multinational firms to Central America; and a renewed push for regional economic integration. At the same time, a concerted effort to improve the rule of law in these countries and reduce corruption is imperative. The direct payoffs of properly executing on these opportunities include inclusive economic growth, foreign investment, job creation, and an overall improved rule of law and governance. Migration pressures and security concerns would also be ameliorated as living conditions improve over time, offering would-be cross-border migrants a better future in their own countries.

Central America must act now to pursue these opportunities and set forth an economic reactivation plan in a COVID-19 world. What policies should governments in Central America enact to create and effectively communicate the incentives to attract nearshoring opportunities? How can the public and private sectors work together to train and empower low-income youth in Central America? How has the pandemic triggered new momentum for regional integration? What is the role of the international community and partners of Central America in promoting the conditions to bolster economic growth and investment?

The Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center of the Atlantic Council has identified three key areas of opportunity: a demographic bonus of a large working-age population; nearshoring of multinational firms to Central America; and a renewed push for regional economic integration.

The Isthmian Ocelots: Mapping Central America’s Opportunities for Reactivation in a COVID-19 World

At a glance, the economic outlook does not bode well for Central America. The IMF anticipates a 3.5-percent average contraction for the region in 2020, albeit less than the projected drop for Latin America and Caribbean, which includes tourism-driven economies and larger countries such as Brazil, Mexico, and Peru that have been particularly hard hit by the coronavirus. The national recovery plans deployed by Central American countries to respond to the immediate and short-term effects of the pandemic, while necessary to mitigate unprecedented health and economic crises, are also demanding increasingly high levels of public expenditure. This poses a threat to fiscal stability, and could weaken the governments’ ability to address rising poverty and inequality. For the informal sector—which employs around 70 percent of the workforce in Central America—the impact is already catastrophic, as public resources are very limited for those outside of the formal economy. The pandemic has also produced external shocks as prices of commodities—the principal exports of Central America—have plunged. As Central American economies are net importers of refined petroleum, the low prices of oil are one of a handful of factors helping them stay afloat.

There are opportunities in the wreckage, though owing less to the nature of the crisis than the political capital for strong response. The severity of this moment should unite Central American leaders from all sectors to develop strategies that seize opportunities for growth, diversification, and integration that have been put aside due to lack of political will or long-term vision, and new ones arising from pandemic-induced global shifts.

Central America: A New Hub for Global Supply Chains?

The US-China trade war has forced companies with China-based supply chains to consider the risks of tariffs, and their effects on imports and exports, against the low costs of Chinese manufacturing. In 2020, the pandemic further accelerated momentum for US companies seeking to diversify their supply chains and potentially relocate closer to the US market to hedge against future global disruptions. According to a recent report analyzing trends in global manufacturing, a significant amount of US firms are moving their supply chains to other low-cost Asian countries or away from Asia entirely, with Mexico becoming a top destination in Latin America as businesses and investors seek the predictability and investment security granted in the recently ratified United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA).8“Trade War Spurs Sharp Reversal in 2019 Reshoring Index, Foreshadowing COVID-19 Test of Supply Chance Resilience,” Kearney, https://www.kearney.com/documents/20152/5708085/2020+Reshoring+Index.pdf/ba38cd1e-c2a8-08ed-5095-2e3e8c93e142?t=1586876044101.

As the Americas become an increasingly attractive alternative, Central America has an opportunity to position itself as the region of choice for nearshoring and foreign investment that can ramp up job creation in the formal sector, while offering companies supply-chain resilience at a competitive cost. To do so, Central America must strategically leverage existing trade relations as well as a large—and growing—young working-age population. Importantly, to become a global supply-chain hub and attract the capital inflow that requires, Central America must significantly improve the rule of law—possibly the largest deterrent for foreign investment in the region.

Central America has an opportunity to position itself as the region of choice for nearshoring and foreign investment that can ramp up job creation in the formal sector, while offering companies supply-chain resilience at a competitive cost.

The most salient value proposition for Central America to become a new center for global supply chains is its unique economic ties to two of the world’s largest economies. Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica—along with the Dominican Republic—are among the few countries in the world that are parties to regional trade agreements with both the United States and the European Union. Under the Central America-Dominican Republic (CAFTA-DR) free-trade agreement and the Association Agreement with the European Union (which also includes Panama), total two-way trade in 2019 was $59 billion and $14 billion, respectively.9“CAFTA-DR (Dominican Republic-Central America FTA),”Office of the United States Trade Representative, https://ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements/cafta-dr-dominican-republic-central-america-fta; “EU-Central America,” European Commission, https://ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/regions/central-america/. Both trade deals have helped to advance economic growth and create new jobs in Central America, while providing the United States and the European Union with a key export market and an opportunity to promote—though not without significant challenges—regional economic integration, cooperation on democratic values, and the rule of law.10Since its passing, the CAFTA-DR trade agreement has not gone without challenges. The United States has submitted three labor complaints under CAFTA-DR dispute-settlement provisions, alleging that the Dominican Republic, Honduras, and Guatemala failed to comply with their commitments. This remains an issue that must be solved among the parties. See more here: “Submissions under the Labor Provisions of Free Trade Agreements,” U.S. Department of Labor’s Bureau of International Labor Affairs, https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/our-work/trade/fta-submissions.

For US firms and other multinational corporations with operations in Central America’s signatory countries, the regional trade agreements (as well as Panama’s free-trade agreement with the United States) offer a well-established blueprint—unlike any other in the region—for exporting goods and services to two of the world’s largest consumer markets. The labor, customs, and rules-of-origin provisions provide the security and stability that firms are seeking, especially at a time of increasing global uncertainty. Specifically, nearshoring firms in the businesses of textiles, agriculture (foodstuffs), and electronics—the main exports under the agreements—have ample opportunity to expand and increase the volume of goods in these sectors using established transportation routes and logistics. Exports to the US market can benefit from even greater supply-chain resilience derived from advantages in strategic geographical proximity to the North American trading bloc. As well, services such as call centers can leverage young bilingual speakers, who will continue to grow in numbers as part of the region’s demographic window that closes around 2033 (see section on Central America’s demographic dividend).

While competitive wages, a young working-age population, and preferential trade access are strong magnets for nearshoring to Central America, they alone will not be enough to successfully attract and sustain the investment needed to fully capitalize on this opportunity. According to the World Bank’s Doing Business 2020 Rankings, Central American economies lag well behind their global peers in the following areas: starting a business, enforcing contracts, dealing with construction permits, registering property, getting electricity, protecting minority investors, and paying taxes.11“Doing Business 2020: Comparing Business Regulation in 190 Economies,” World Bank Group, 2020, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/32436/9781464814402.pdf.

While competitive wages, a young working-age population, and preferential trade access are strong magnets for nearshoring to Central America, they alone will not be enough to successfully attract and sustain the investment needed to fully capitalize on this opportunity.

Policymakers across the region must be intentional about fostering a more business-friendly climate for multinational firms. Reducing red tape as well as modernizing and decentralizing key government processes to ensure efficiency and accountability are relatively low-cost (both politically and financially) first steps with a high potential upside. Properly enforcing public contracting laws—a longstanding challenge in Central America and across Latin America—will be critical, especially at a time of increased fiscal and monetary challenges due to the pandemic. But, if Central America is to lock in foreign investment over the long term, leaders from across the public and private sectors must come together to implement integral and viable solutions to address deep-seated impediments for growth, including economic informality, politicization of justice, violent crime, and insecurity, and—in the particular case of Nicaragua—political instability and widespread social repression.

Costa Rica in Focus

The restructuring of value chains through nearshoring offers a distinct opportunity for Costa Rica. Companies are looking for certainty in today’s context. Shortening the supply chains is an option, but that alone does not necessarily improve resilience.12“Why Costa Rica is a Strategic Destination for Supply Chain Rethinking,” Costa Rican Investment Promotion Agency (CINDE), July 30, 2020,”https://www.cinde.org/en/news/news/why-costa-rica-is-a-strategic-destination-for-supply-chain-rethinking. Instead, diversification of supply-chain location and suppliers can provide the best results. Costa Rica has a long-standing track record of a highly qualified and healthy workforce. According to the World Economic Forum, Costa Rica ranks as the top country in Latin America in human capital; the top country in innovation efficiency; the number-two country in the region in the Global Innovation Index (after Chile); and the top-ranked country in Latin America in university-industry collaboration in research and development (R&D).13“The Global Competitiveness Index 2017-2018: Costa Rica,” World Economic Forum, http://www3.weforum.org/docs/GCR2017-2018/03CountryProfiles/Standalone2-pagerprofiles/WEF_GCI_2017_2018_Profile_Costa_Rica.pdf. Costa Rica recently became a member of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)—the first one in Central America—which will mean more competitive laws and practices, better education policies, and improved governance.

Costa Rica’s free-trade-zone regimes—which currently include a total of seven manufacturing parks and twenty-five service parks—offer 100-percent tax exemption (with no expiration) on custom duties for imports and exports; interest income; withholding tax on royalties, fees, and dividends; sales tax on local purchases of goods and services; and stamp duty. For all sectors outside the greater metropolitan area, the benefits expand to a complete income-tax exemption for the first twelve-year period, followed by a 50-percent income-tax exemption for the subsequent six years.14“Incentives,” Costa Rican Investment Promotion Agency (CINDE), https://www.cinde.org/en/why/incentives.

Transportation infrastructure and costs, as well as the country’s fiscal situation, are obstacles that companies looking to relocate will have to face. The 2018 World Economic Forum ranks Costa Rica’s road quality and infrastructure as second to last.15“The Global Competitiveness Index 2017-2018: Costa Rica,” World Economic Forum. The poor quality of Costa Rica’s road network also results in significant losses for companies, sometimes up to 12 percent of the value of exported goods.16Jordan Schwartz, et al., “Logistics, Transport, and Food Prices in LAC: Policy Guidance for Improving Efficiency and Reducing Costs,” World Bank, August 2009, http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/751921468270863216/pdf/879330WP0Box380ssionalPapers0August.pdf. In 2020, Costa Rica will invest 1 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) in transportation infrastructure; the investment should be at least three times that in order to help the country’s competitiveness.17Esteban Arrieta, “Costa Rica Debería Invertir el Triple para Superar Rezago en Infraestructura,” La Republica, November7, 2019, https://www.larepublica.net/noticia/costa-rica-deberia-invertir-el-triple-para-superar-rezago-en-infraestructura. In addition to the high costs of transportation and low investments in infrastructure, Costa Rica’s long-term fiscal health is worrisome. The fiscal deficit for 2019 reached 7 percent of the country’s GDP, the highest in almost forty years. The precariousness of the situation has not gone unnoticed by Fitch and Standard & Poors, which have downgraded the country rating to B with a negative outlook, while Moody’s has downgraded its rating to B2 with negative outlook for 2020.18“Costa Rica—Credit Rating,” Trading Economics, https://tradingeconomics.com/costa-rica/rating#:~:text=Standard%20%26%20Poor’s%20credit%20rating%20for,at%20B%20with%20negative%20outlook. The result: despite Costa Rica’s many advantages, heightened country risk may keep investors away.

Central America’s Demographic Bonus

For Central American countries, the second half of the twentieth century was marked by internal conflicts, natural disasters, and start-and-stop attempts to scale their economies by moving toward greater regional integration. During this time, countries relied mostly on agricultural and primary exports. But, important shifts in demographic patterns that have translated to visible economic and social progress in other industrialized countries and regions are now occurring in a non-armed conflict in Central America—where the working-age population, and therefore the workforce, grows more rapidly than the older and younger populations. The “economic growth potential that can result from shifts in a population’s age structure, mainly when the share of the working-age population is larger than the non-working-age share of the population” is what the United Nations Population Fund has defined as the demographic dividend. An Atlantic Council report, Latin America and the Caribbean 2030: Future Scenarios, found that “the dependency ratio in Central America will peak in 2033.19”Jason Marczak, et al., Latin America and the Caribbean 2030: Future Scenarios, Atlantic Council, 2016, 55, https://publications.atlanticcouncil.org/lac2030/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/LAC2030-Report-Final.pdf. Other forecasts place the average year for Central America to reach this milestone around 2042, and the United Nations (UN) predicts the population pyramid in Central America will flatten by 2050.20Daniela González, “Caracteristicas Demograficas de los Paises de Mesoamerica y el Caribe Latino,” Comision Económica para America Latina y el Caribe, https://www.cepal.org/sites/default/files/events/files/caracteristicas_demograficas_mesoamericaycaribelatino.pdf; Andres Cadena, et al., “Unlocking the economic potential of Central America and the Caribbean,” McKinsey & Company, April 12, 2019, https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/americas/unlocking-the-economic-potential-of-central-america-and-the-caribbean. With domestic product growing at a 3.5-percent average rate, Central America has experienced the strongest growth in Latin America for the past decade.21Marczak, et al., Latin America and the Caribbean 2030: Future Scenarios.

On the other hand, the socioeconomic progress from the last few years—in large part, derived from the increased productivity that normally accompanies the demographic bonus—is at risk of evaporating as Central America grapples with the pandemic and economies are paralyzed over sanitary concerns. However, compared to its Latin American peers, Central America has both a distinct demographic opportunity and threat (varying by country), which it must address by putting people to work in the formal labor markets. Failure to employ and occupy a large young workforce can be a security and welfare risk, as young men and women may turn to illicit activities to create a livelihood, and will not contribute to the state’s coffers, which depend on tax revenue and social-security collections to support retirees and public services.

Failure to employ and occupy a large young workforce can be a security and welfare risk.

Seizing the Demographic Window

The rest of Latin America, for the most part, has already seen the demographic window of opportunity come and go, and the trend will not be reversed anytime soon. The fertility-rate average, meaning “the average number of children that would be born per woman if all women lived to the end of their childbearing years and bore children according to a given fertility rate at each age,” in Latin America is 2.05, below the replacement rate of 2.1 and the 2020 global fertility rate of 2.4.22Alicia Bárcena, “America Latina Envejece,” Comision Económica para America Latina y el Caribe, January 7, 2011, https://www.cepal.org/sites/default/files/article/files/43934-2011.07.01-cambios-demograficos-americaeconomia.pdf. For 2035, the estimate is that Latin America’s fertility rate will drop to 1.81.23González, “Caracteristicas Demograficas de los Paises de Mesoamerica y el Caribe Latino;” Cadena et al. “Unlocking the economic potential of Central America and the Caribbean.” Fertility rates are an important and telling data point for the demographic bonus described in the previous section. As fertility rates decline, the first part of the pyramid to shrink is the base, which translates into fewer young dependents for a nation to support.24To illustrate the different demographic stages for Central America, consider the following 2018 fertility rates: 2.87 in Guatemala, 2.48 in Honduras, 2.46 in Panama 2.42 in Nicaragua, 2.05 in El Salvador, and 1.76 in Costa Rica. The middle section of the pyramid, comprising working-age citizens, budges out as this section of the population grows as a result of a country’s past fertility rates, as does the tip of the pyramid, although at a slower pace.

The current population forecasts and trends bode well for Central America’s future, but a robust young workforce does not necessarily translate into economic growth. If unoccupied, working-age men and women can turn to criminal activities and pose a security risk for the region and hemisphere. Likewise, if countries fail to think and invest in a long-term strategy with a focus on increasing productivity, they may end up with an aged and burdened population.

The experience of East Asia, including Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and Singapore, is considered one of the first and most successful examples of a region exploiting the demographic bonus, and offers best practices for how to capitalize on the demographic bonus. For example, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, the aforementioned countries focused on creating high-value jobs in “the service and manufacturing sectors of the economy.”25Andrew Mason, “Capitalizing on the Demographic Dividend,” University of Hawaii, 2002, http://www2.hawaii.edu/~amason/Research/UNFPA.PDF. Central American countries, for the most part, have been incapable of keeping job creation and opportunities at pace with the growing workforce numbers. In 2017, the annual labor-force increase in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras surpassed 350,000 people, with only 34,500 jobs created in the formal economy, and more than 290,000 in the informal economy.26Manuel Orozco, “Central American Migration: Current Changes and Development Implications,” Inter-American Dialogue, November 2018, thedialogue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/CA-Migration-Report-Current-Changes-and-Development-Opportunities1.pdf.

Likewise, in the East Asian “tiger economies,” of Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan which underwent rapid industrialization and maintained high growth rates of more than seven percent a year starting in the 1960s, reforms were introduced to attract women to the labor market.27Simon Rabinovitch and Simon Cox, “After half a century of success, the Asian tigers must reinvent themselves,” The Economist, December 5, 2019, https://www.economist.com/special-report/2019/12/05/after-half-a-century-of-success-the-asian-tigers-must-reinvent-themselves. These high-income economies took advantage of the growing taxpayer base and declining number of young dependents to invest in education, without having to increase taxes.28Ibid.

Migration

Economies need young workers to grow. As populations grow older, the state relies on each working-age person to pay taxes to cover social services for a growing number of older citizens, and to guarantee a functioning state and public services. Europe, for example, would be in trouble and the social welfare overburdened if the region was unable to attract immigrants. Currently, the European Union’s average fertility rate is 1.59, well below the global replacement rate of 2.1.29“Over 5 million births in EU in 2017,” EuroStat, March 12, 2019, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/9648811/3-12032019-AP-EN.pdf/412879ef-3993-44f5-8276-38b482c766d8#:~:text=In%202017%2C%205.075%20million%20babies,compared%20with%201.60%20in%202016. For the past decade, immigrants have accounted for more than 70 percent of Europe’s increase in workforce. In the United States, according to Census Bureau projections, immigrants are poised to “overtake natural increase (the excess of births over deaths) as the primary driver of population growth for the country” by 2030, though this is primarily due to the low birth rates from the US-born population and not necessarily because of increased immigration levels.30Jonathan Vespa, et al., “Demographic Turning Points for the United States: Population Projections for 2020 to 2060,”United States Census Bureau, February 2020, https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2020/demo/p25-1144.html. Already today, immigrants are responsible for more than 47 percent of the increase in workforce.31“Is migration good for the economy?,” Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, May 2014, https://www.oecd.org/migration/OECD%20Migration%20Policy%20Debates%20Numero%202.pdf. A study by the OECD finds that “in most countries, except in those with a large share of older migrants, migrants contribute more in taxes and social contributions than they receive in individual benefits.”32Ibid. For this reason, seizing Central America’s demographic bonus and successfully employing its native young workforce at home, or within the region, is crucial.

“…seizing Central America’s demographic bonus and successfully employing its native young workforce at home, or within the region, is crucial [for the region’s recovery].”

In 2017, more than 4.4 million Central Americans emigrated, representing almost 10 percent of the region’s total population.33Infographic Migration and Remittances in Central America,” BBVA Research, October 8, 2019, bbvaresearch.com/en/publicaciones/infographic-migration-and-remittances-in-central-america/. Currently, the working-age population in Central America (between twenty and thirty-nine years old) is among the most likely to emigrate—primarily to the United States.34Ibid.

Nicaraguans, however, mostly migrate to neighboring Costa Rica and are important contributors to their southern neighbor’s GDP. While they make up around 9 percent of Costa Rica’s total population, Nicaraguans contribute more than 11 percent of their southern neighbor’s GDP. These emigration patterns—driven by different factors in each of the countries, but mostly due to citizen insecurity, violence, and lack of economic opportunities—are preventing Central America from making the most of its demographic bonus. In addition, recent studies suggest that migration can be “self-reinforcing.”35“Central American Migration: Root Causes and U.S. Policy,” Congressional Research Service, June 13, 2019, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/IF11151.pdf/. In other words, as citizens leave and settle in a new country, they may encourage friends and family to migrate as well. This is especially true with the power and reach of social media today.36Maria Fernanda Perez Arguello, “What Drives Migrant Caravans? Violence, Impunity and Social Media,” TheHill, January 17, 2019, https://thehill.com/opinion/immigration/425667-what-drives-migrant-caravans-violence-impunity-and-social-media. While the brain drain has proven detrimental to Central American countries, the remittances sent back home help offset some of the economic losses from a smaller workforce. Remittances sometimes make up one fifth of Central America’s individual economies.37“Infographic Migration and Remittances in Central America,” BBVA Research, October 8, 2019, bbvaresearch.com/en/publicaciones/infographic-migration-and-remittances-in-central-america/. Although remittances dropped sharply as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic in the first half of 2020—especially in April, when much of the United States, the main destination of Central American immigrants, was closed down—a recent analysis by the Pew Research Center shows that remittances are slowing picking up again, though they will probably not reach 2019’s record levels.38Luis Noe-Bustamante, “Amid COVID-19, Remittances to Some Latin American Nations Fell Sharply in April, Then Rebounded,” Pew Research Center, August 31, 2020, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/08/31/amid-covid-19-remittances-to-some-latin-american-nations-fell-sharply-in-april-then-rebounded/.

Guatemala in Focus

More than half of the population in Guatemala is in the productive age category, but almost six in ten people live in poverty. This is, in part, because of the high rate of informality, where more than 70 percent of the population that is active in the economy is in the informal sector, as street vendors or in domestic or non-remunerated labor, which hardly contribute to the country’s productivity.39Cecilia Barria, “Elecciones en Guatemala: Qué es el ‘Bono Demográfico’ y por qué Puede ser Clave en el Futuro de la Economía de ese País,” BBC Mundo, June 12, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-48589321; Hugo Maúl Rivas, “Bajo Desempleo y Alta Informalidad,”CIEN, April 9, 2019, https://cien.org.gt/index.php/bajo-desempleo-y-alta-informalidad/. For comparison, the Latin American average for labor informality is 53 percent.40“OIT: Cerca de 140 Millones de Trabajadores en la Informalidad en América Latina y el Caribe,” Organización Internacional del Trabajo, September 25, 2018, https://www.ilo.org/americas/sala-de-prensa/WCMS_645596/lang–es/index.htm#:~:text=La%20tasa%20de%20informalidad%20de,ni%20por%20la%20seguridad%20social. The 2.8-percent official unemployment rate is low compared even to developed economies such as Spain (14-percent unemployment), but the real concern lies in the size of the country’s informal economy.41Barria, “Elecciones en Guatemala.” Urgent reforms in Guatemala will translate into a transition into formal economic activities that will employ young men and women for the jobs of tomorrow—including in digital—and will pay dividends down the road. Currently, in Guatemala, the service sector represents the largest share of GDP (62.1 percent) and employs more than half of the formal working population in key sectors including tourism, customer-service (call centers), financial-services, banks, and retail. The table below shows the breakdown of economic activity by sector in Guatemala in 2019. As a matter of comparison, while almost one quarter of the country’s GDP is generated by the industrial sector, the number jumps to 40 percent for the United States.42Geldi Munoz Palala, “El Bono Demográfico se Escapa de la Región,” Periódico, October 22, 2018, https://elperiodico.com.gt/inversion/2018/10/22/el-bono-demografico-se-escapa-de-la-region/.

| Breakdown of Economic Activity By Sector | Agriculture | Industry | Services |

| Employment By Sector (in % of Total Employment) | 29.2 | 20.6 | 50.2 |

| Value Added (in % of GDP) | 10.0 | 24.6 | 62.1 |

| Value Added (Annual % Change) | 2.5 | 2.8 | 3.3 |

The demographic window of opportunity for catalyzing economic growth and development will not remain open indefinitely—and, as discussed in this paper, is not enough to alleviate the impending economic recession and difficulties of the coming years, or to guarantee economic growth and development.

Now is the time for Central American nations to invest in policies, new sectors, and industries that will reduce educational and economic disparities, help train citizens for productive work in the changing economic landscape, create jobs for the growing labor force, attract women to the labor market, and prepare countries to care for an elderly population. Estimates from the Inter-America Development Bank show that an improvement in emerging human capital in the region could translate into a 33-percent increase in GDP per capita with respect to a base scenario, an especially important investment in a difficult COVID-era.43Jordi Prat, et al., “Inclusive Growth: Challenges and Opportunities for Central America and the Dominican Republic,” Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), February 2018, https://publications.iadb.org/publications/english/document/Inclusive-Growth-Challenges-and-Opportunities-for-Central-America-and-the-Dominican-Republic.pdf.

The Case of Nicaragua

By: Enrique Bolaños

The coronavirus pandemic in Nicaragua is amplifying an already-strained economy due to the political instability experienced in recent years. The United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean estimates a GDP contraction of 8.3 percent in 2020, after it contracted by 4 and 3.9 percent in the previous two years.44“Fitch Affirms Nicaragua at ‘B-’; Outlook Revised to Negative,” FitchRatings, June 17, 2020, https://www.fitchratings.com/research/sovereigns/fitch-affirms-nicaragua-at-b-outlook-revised-to-negative-17-06-2020; “The World Bank in Nicaragua: Overview,” World Bank, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/nicaragua/overview. The pandemic is aggravating existing tensions generated by the country’s traditional institutional and competitiveness challenges.

Nicaragua’s lag in development is largely explained by the historical instability of its democratic system. After more than forty years of the Somoza family dictatorship, the 1979 Sandinista revolution promised new hope. But, a decade of economic mismanagement from the Sandinista government caused the country’s GDP per capita to regress to the same level as twenty-five years earlier. Following three democratic governments from 1990 to 2006, the Sandinistas came back to power in 2007. Since then, democratic institutions and the rule of law have eroded, and Nicaragua is now considered an authoritarian regime. Meanwhile, the economic structure has remained relatively stagnant during this period, characterized by low levels of competitiveness and concentration on a few exports of primary products and apparel manufacturers, with little value added.

An economic recovery in the face of COVID-19 requires short- and medium-term interventions and, once the emergency is over, structural changes for sustainable development. The immediate priorities must be to protect employment and avoid company closures. In the short term, this involves strengthening the liquidity of companies and helping them prepare to operate under a “new normal,” in which there is no coronavirus vaccine widely available for the next twelve to eighteen months. Fiscal support and policies aimed at increasing financing for the productive sector, especially for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), is crucial, as is technical support for companies to implement special operating protocols that guarantee the safety of workers and clients. Finally, adoption of basic digital capabilities into the operating model of companies is essential to recover lost sales and improve efficiency.

In the medium term, Nicaragua needs to stimulate engines of growth. Public investment and agri-food exports seem to be the most promising ones. The government should activate an investment plan in infrastructure that can catalyze productivity. First, it should focus on border crossings and better customs processes to facilitate trade. Second, it should invest in broadband infrastructure to improve access, cost, and quality of Internet connectivity. Third, it should prioritize investment in technology to streamline and digitize specific processes aimed at minimizing red tape. At the same time, the country should implement a development plan for the agri-food sector that encourages export growth and adoption of new technologies for precision agriculture.

In the long term, in addition to strengthening the democratic system, generating prosperity requires a transformation of the economic structure. This transformation must diversify the existing basket of exports and evolve toward activities with higher value added. The country must take advantage of the changes in globalization patterns in the post-COVID-19 era, its geographical position, and its preferential access to the main markets in the United States, Europe, and Asia. It is essential to implement programs in strategic sectors that allow for enhancing competitiveness and sophistication in production models, seeking synergies with world-class players. Policies and investments are also required to develop the human and physical capital to support this transformation.

A Renewed Push for Central American Economic Integration

The pandemic and its devastating economic effects have also given advocates of Central American integration a renewed opportunity for a project as old as the region’s independence. Despite clear benefits for economic growth and regional prosperity, integration has been stalled due to lack of coordinated political alignment and long-standing technical and practical hurdles. The unprecedented and unforgiving shock of COVID-19 can restart a serious, comprehensive, and strategic public debate on Central American economic integration, in spite of existing schisms among the countries.

The unprecedented and unforgiving shock of COVID-19 can restart a serious, comprehensive, and strategic public debate on Central American economic integration, in spite of existing schisms among the countries.

Central America integration has been talked about over the past sixty years. In 1960, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, and Nicaragua (and later Costa Rica) signed a UN-backed agreement aimed at creating an EU-style single market. Following ratification of the General Treaty of Central American Economic Integration (GTCAEI), Central America saw its intraregional trade increase by seven times, and saw significant advances in industrialization and manufacturing.45Dominique Desruelle and Alfred Schipke, “Central America: Economic Progress and Reforms,” International Monetary Fund, 2008, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/dp/2008/dp0801.pdf. But, the integration project saw a twenty-year hiatus due to the armed conflicts across the region. Integration discussions were picked up again during the early 1990s under the Tegucigalpa Protocol, which established the institutional framework—the Central America Integration System (SICA)—to carry forward integration based on a vision of “peace, democracy, and development.”46“Propósitos del SICA,” Sistema de Integración Centroamericana, https://www.sica.int/sica/propositos In 1993, under the Guatemala Protocol, parties to the 1960 GTACEI “committed themselves to achieve, on a voluntary, gradual, progressive and complementary way, the Economic Union of Central America.”47“Tegucigalpa Protocol to the Charter of the Organization of Central American States (ODECA),” Sistema de Integración Centroamericana, December 13, 1991, https://www.sica.int/documentos/tegucigalpa-protocol-to-the-charter-of-the-organization-of-central-american-states-odeca_2_320.html. Since then, major wins toward Central American economic integration include a semi-completed customs union (Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador currently have one), a common external tariff, and some advances in the free movement of people, capital, and services.48“Unión Aduanera,” Sistema de Integración Centroamericana, https://www.sica.int/iniciativas/aduanas. Unfortunately, short-term vision and rivalries between Central American political leaders have not supported GTCAEI’s full implementation.

Full economic integration in Central America can better position the region for sustained economic growth and competitiveness in a global economy adapting to disruptions from the coronavirus pandemic. The region’s second-largest trading partner—after the United States—is Central America itself. Intraregional trade between Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica accounts for 27 percent of total exports and 13 percent of total imports. With a combined population of forty-five million producing $400 billion in GDP—ranking fourth in Latin America and nineteenth in the world, respectively—an integrated Central America can more efficiently allocate economic resources and investment, access new intraregional markets, boost foreign trade, improve commercial agreements and enter new ones with increased bargaining power, increase market diversification, attract foreign direct investment, and build supply-chain resilience. Economic integration is also an opportunity—especially at a time when countries in the region face the same external shocks, from global health and trade to climate change and geopolitics—to deepen political, security, social, cultural, and environmental ties. While advances on these fronts have been made through SICA, the coronavirus pandemic has alerted the region to the importance of forging stronger relations on public health, good governance, and economic resilience.49“Algunos Logros del SICA,” Sistema de Integración Centroamericana, https://www.sica.int/Iniciativas/inicio.

Full economic integration in Central America can better position the region for sustained economic growth and competitiveness in a global economy adapting to disruptions from the coronavirus pandemic.

SICA and other regional forums at the presidential, ministerial, and central-bank levels have facilitated important integration discussions and helped to set the agenda for alignment and coordination on specific integration issues. But actual adoption and implementation remains a challenge. An integrated Central America will have increasead absorptive capacity to withstand the unprecedented global disruptions and unparalleled uncertainty in trade and supply chains. Can the coronavirus pandemic provide renewed momentum to advance the implementation of regional economic integration? Political leaders must put their differences aside, prioritize the integration agenda, and take collective action toward implementation. This means taking specific steps at the regional and country levels to advance implementation in policy, fiscal, and monetary coordination; tax harmonization; adoption of common standards and regulations; and financial sector integration. At the country level, leaders should prioritize investment in cross-border infrastructure for secure and reliable transportation and energy connectivity, with financial and technical assistance from regional and international banks, such as the Central American Bank for Economic Integration (CABEI) and the World Bank.

Central America Customs Union: A Requisite for Success?

By: Salvador Paiz

Individually, Central American countries are relatively small markets. In the past, as companies saturated a market in their respective industries, they looked to domestic diversification as a source for growth. The main competency was being able to thrive despite the nuances of their home country. Nevertheless, roughly forty years ago, companies began to expand differently: relying less on diversification, but growing the core business throughout Central America, where the size of the addressable market is more attractive, roughly equivalent to Chile in terms of GDP or Colombia in terms of population.

The private sector has been a longtime champion for Central American integration. Governments, on the other hand, have lacked leadership and vision for this ambitious project. Of course, there are a few initiatives that foster regionalization, such as the Secretariat for Central American Economic Integration (SIECA), which are important, but are also insufficient. What policy actions can Central American governments introduce in the short term to accelerate regional integration?

Customs offices in Central America are notoriously slow, and there is a lack of coordination between them. Digitalization of customs offices, including their integration into a common systems platform, would significantly speed up the transportation process and reduce waiting times at borders. Customs offices should have a list of “known shippers” and receive digital cargo documents ahead of time, akin to the US-Mexico Free and Secure Trade (FAST) Card program, “a commercial clearance program for known low-risk shipments entering the United States from Canada and Mexico.”50“FAST: Free and Secure Trade for Commercial Vehicles,” US Customs and Border Protection, https://www.cbp.gov/travel/trusted-traveler-programs/fast. This would allow for contactless and uninterrupted flow through the borders, while enhancing traceability and collection of duties.

Companies have to pay, at each national border, taxes for services, transit, import duties, and value-added taxes—and they have to pay differently in each country. Of course, the optimal result would be achieved with a customs union in which goods can move freely and be exempt from heterogenous duties. At a minimum, a unified value-added tax code would reduce the complexities and economic distortions of having different rates and exempt goods. Lastly, there should be no retention of income tax or double taxation for services provided to other companies, or even among subsidiaries of the same company within a region.

Another idea is to centralize sanitary licenses and trademark registrations. Authorities should be able to create and centralize one—and only one—process when it comes to these types of records. A “single window” to register in all countries of Central America at the same time would be a great incentive for companies to relocate to the isthmus.

The size of Central America should, in theory, make it an attractive market. The lack of uniformity and consistency in conducting cross-border trade and business leads to multi-step bureaucracies that hinder economic integration, and therefore, diminish the prospects for economic development. If the countries of Central America act as one, they could finally become a market that offers the economies of scale that can lead to new market opportunities, job creation, and enhanced regional competitiveness.

Fostering the Minimum Conditions for Growth: Recommendations for Governments, the Private Sector, and the International Community

The pandemic has forced countries to look inward as they scramble to strike the right balance between saving lives and saving the economy. In Central America, countries have a unique opportunity to also look beyond their borders for dialogue and cooperation, especially on how to unite in the face of external forces impacting the entire region. Central American nations can take the following concrete steps—on a national and regional level—to embark on a united path toward recovery and growth.

Governments

- Convene multisectoral task forces to propose policy actions for kickstarting economic recovery. Central American countries must unite around the national cause of economic reactivation. This means convening multisectoral task forces—from current and past administrations, private-sector leaders, multilateral representatives, and other sectors—to jointly discuss how to best kickstart economic reactivation in their countries. National task forces should then filter into cross-border discussions on regional issues. Key agenda items could include lifting investment restrictions to effectively attract supply chains and potential new businesses, offering special visas for foreign nationals working remotely to incentivize and support tourism, enacting legislation to combat corruption in procurement and public contracting with innovative digital technologies and processes, and informing on best practices from economic-recovery strategies in other countries outside of the region. These task forces should also propose specific actions for longer term and sustained economic recovery such as bridging some of the political and policy gaps around implementation of regional economic integration.

- Tackle long-standing barriers to business investment to encourage nearshoring. Governments in the region should improve governance, increase transparency and public accountability, and promote business-friendly environments. If Central America is to have economic growth, especially in a post-pandemic world, it must continue the long-term work toward building public trust, respecting the rule of law, transparency, and strengthening institutions. The independence of the judiciary—a particular challenge in Guatemala—must be protected to ensure trust in the judicial system. At a time when emergency powers provide ground for executive overreach and loosened regulations and supervision around procurement, anti-corruption missions—especially those in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras—must show they are serious about tackling graft. Federal prosecutors and judges require additional capacity building and technical assistance to effectively conduct and process corruption investigations. Reducing red tape and streamlining key bureaucratic processes related to business and investment—with the help of digital technologies—must also be at the top of the agenda. Tax and regulatory reform must be aimed at reducing informality, which accounts for more than 60 percent of the Latin American workforce and is a major impediment for sustained, inclusive growth.

- Invest in developing the human capital needed for a changing global economy. Governments should prioritize investment in workforce training and capacity building for jobs in the manufacturing and services sectors, in accordance with global demand, especially those tied to nearshoring opportunities. In the short term, governments must partner with the private sector and civil society, with the specific resources and know-how to maximize the impact and scale of workforce training and foster entrepreneurship and innovation. In the medium to long term, governments should promote and invest in education and vocational programs tailored to developing the knowledge and skills that meet the demands of the labor market and prepare workers for the jobs of the future. Developing human capital and increasing productivity in Central America are the most important variables for taking full advantage of the demographic dividend over the next decade.

Private Sector and Civil Society

- Invest in new workforce and on-the-job training programs that align with business demands. The Central American private sector must be a crucial player in rapidly developing human capital before the relatively narrow demographic window closes in 2033. Private-sector leaders have the capability to implement long-term strategies—as opposed to short-term government-led efforts—focused on workforce development, education for the jobs of tomorrow, and vocational and technical programs with real-life skill trainings (education-to-employment programs). The public sector must help these private-sector leaders in facilitating these opportunities, engaging in public-private partnerships, and removing red tape for private-sector-led capacity-building efforts. Support and buy-in from civil society groups is key here, especially in longer-term education in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM). Civil society buy-in can help to ensure that education and capacity building efforts are gender and racially inclusive.

- Partner with governments on anti-corruption efforts. Weak rule of law continues to be a major impediment for investment in Central America. The private sector can be a crucial partner in helping to decentralize, modernize, and digitalize key procurement and public contracting processes that are most vulnerable to graft. A private sector that can drive growth and is committed to transparency and accountability is an important sign for foreign investors seeking business opportunities in Central America, especially now with multinational firms exploring supply-chain relocation.

International Community

- Provide financial and technical assistance amid pandemic response. As with other countries hard hit by the pandemic, Central American countries have seen weakened fiscal positions and strained public resources. Multilateral development banks and international financial institutions must play a critical role in providing necessary finaning to Central American economies. For example, the IMF can provide financial assistance, and support for debt restructuring processes. The World Bank (WB) and the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) should expand their technical and financial support in various areas of the public and private sectors. This assistance will be necessary to keep Central American economies afloat and must be complemented by local economic recovery strategies by local leaders, but both external and internal plans must be tied to assurances in strengthening the rule of law.

- Enhance intraregional connectivity to attract investment and drive integration. To attract foreign investment and encourage regional integration and sustainable economic growth, the international community can be a key ally and help governments determine infrastructure and energy investments to enhance intraregional connectivity as well as transregional connectivity—for example, in northern Guatemala along Mexico’s southern border. Political leadership at the national level must support regional financial institutions such as the IDB and Development Bank of Latin America—with strategic advice and support from international organizations such as the World Bank—to deploy the required capital and the technical capabilities to lead infrastructure investments. CABEI must also be a key player in financing infrastructure and energy projects to improve regional economic integration. Fast and secure transportation routes and cheap, reliable energy are top requirements for foreign investment and economic integration.

- Deepen and expand foreign investment partnerships in Central America. The United States, as Central America’s most important trade and investment partner, must target investments aimed at generating new employment opportunities and supporting sectors crucial for inclusive economic growth and regional integration. Local leaders from the public and private sectors must provide buy-in and support for local and foreign investment efforts in infrastructure and energy projects accompanied by strategic investments to reduce insecurity and strengthen the rule of law, with clear benchmarks and metrics for measuring impact. These metrics must be effectively communicated to ensure full transparency and long-term support. Bilateral agencies must also play a critical role, such as the U.S. government’s development finance institution, the Development Finance Corporation (DFC). Beyond the United States, any international investment to Central America must further the rule of law, create job opportunities for local communities, and provide viable terms and conditions for loan repayments.

Central America’s much-needed reforms are not only relevant in today’s pandemic-shocked world, but also necessary for the region to effectively seize unique opportunities for long-term, sustained growth. The urgency of the moment and the magnitude of the multi-dimensional crisis from COVID-19 punctuates the need for Central America to address historic challenges and traditionally weak institutions from all angles and sectors—public, private, civil society, and the multilateral and international community. For Central America to emerge like a phoenix from its ashes, concerted action must happen now.

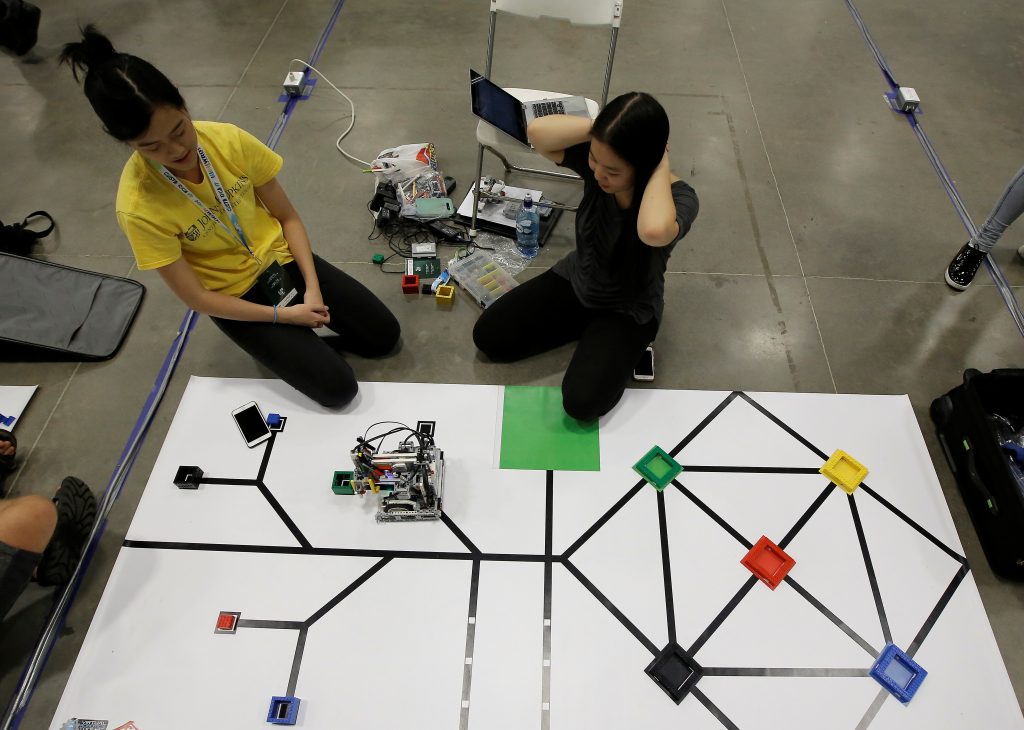

Image: A participant prepares a miniature robot during the World Robot Olympiad at a convention center in San Rafael de Alajuela, Costa Rica November 10, 2017. REUTERS/Juan Carlos Ulate