PeaceGame Venezuela: Pathways to Peace

In October 2019, PeaceGame Venezuela convened global leaders in Washington, D.C. to advance thinking around how Venezuelans and the international community should prepare for the potential of complete state collapse in Venezuela. This undesirable scenario must be considered as the domestic situation and the regional and global implications further deteriorate.

This high-level crisis simulation was a collaboration between Foreign Policy, the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center, and Florida International University.

PeaceGame Venezuela considered alternative, actionable strategies that could be taken by the international coalition of countries supporting democracy and multilateral organizations as well as how actors such as Russia, Cuba, and illegal armed groups may respond. Critically, the simulation played out how the Maduro regime may seek to leverage its influence and new actions that could be taken by Venezuela’s democratic forces. The outcomes and recommendations from the simulation will help inform real-world strategy. Among the findings:

- International stakeholders who support democracy must develop a coordinated and agile action plan now that can prevent, or, if collapse occurs, mitigate the very real regional and global impacts.

- Democratic forces in Venezuela must be strategic in planning how to mitigate the influence of poorly intentioned external actors who could accelerate and take advantage of state collapse.

- Communicable disease outbreaks and contagion represent real risks, necessitating preparation and coordination among regional health ministries and experts to contain potential outbreaks.

- Island nations are among the most vulnerable to spill-over effects from the crisis, requiring economic, humanitarian, and security assistance from multilateral development banks or regional institutions.

OVERVIEW

On October 2, 2019, PeaceGame Venezuela convened global leaders in Washington, D.C., to think through the potential for worsening security and humanitarian scenarios in Venezuela and explore ways to effectively respond. This high-level crisis simulation was produced by Foreign Policy in partnership with the Atlantic Council and Florida International University, with support from PeaceGame founding partner the United Arab Emirates.

FP PeaceGames are scenario-based crisis simulations that offer participants a chance to address the challenges of diplomacy and peacebuilding with the same creativity and focus that has been traditionally devoted to war games. With the primary goal of peacefully resolving conflicts, these simulations also strengthen communication among stakeholders, enable more strategic and effective planning, and inform policy, investment, and resource allocation decisions. Given the rapidly deteriorating humanitarian and security situation in Venezuela and cascading impacts on the region, PeaceGame Venezuela was convened to think through alternative, actionable strategies to stabilize the current situation, mitigate compound risks, and provide near-term humanitarian relief.

The outcomes and recommendations from the simulation can help inform real-world strategy and policy planning.

The October event brought together officials and experts from the region and around the world to work through a scenario that incorporated a range of possible crises that could materialize in Venezuela in the event of complete state collapse. The scenario was developed through in-depth research and consultation with regional experts and incorporated specific events that could be triggered by the deteriorating situation and that would amplify spillover effects for the region. Throughout the course of the PeaceGame, participants grappled with worsening economic conditions, managed trafficking and migration issues, and took action to mitigate risks within and beyond the region.

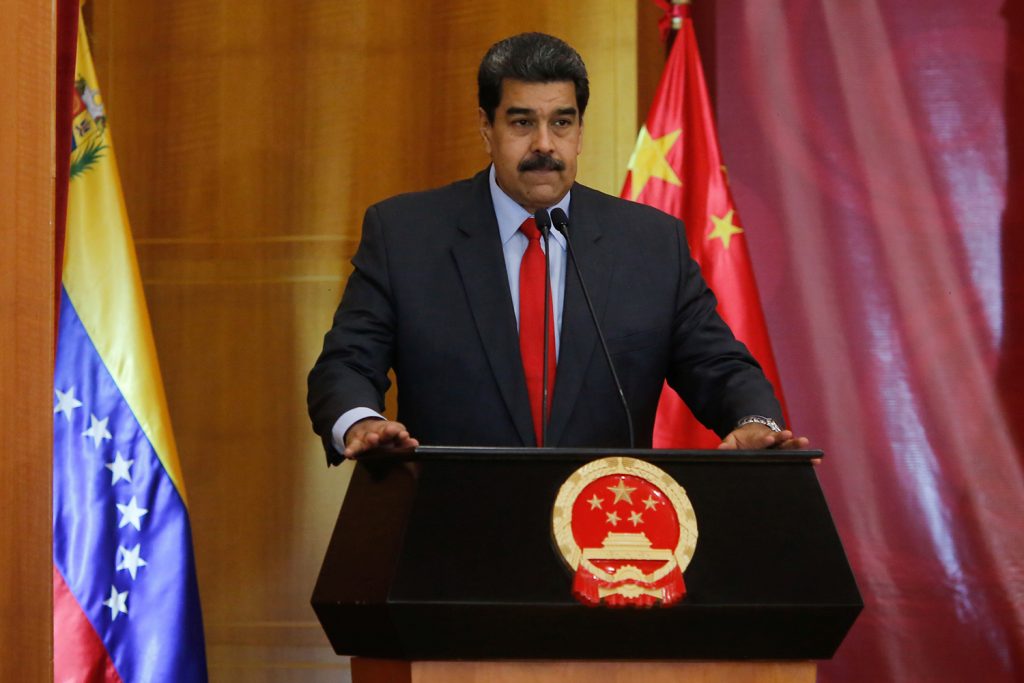

Participants included ambassadors, ministers, current and former military officers, and experts from across the region who are directly involved in policy and security planning and for whom the unfolding crisis in Venezuela is having a direct impact. The participants, several of whom were sitting face-to-face for the first time, played the roles of varying key stakeholders, including the interim government of Venezuela, the regime of Nicolás Maduro, Colombia, regional neighbors (Brazil, Ecuador, Peru, and Chile), Russia, China, Cuba, global supporters of the interim government, armed groups (the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia [the FARC] and the National Liberation Army [ELN]), colectivos, the United States, the United Nations, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and the Caribbean Community (CARICOM). While additional actors are influencing dynamics in the region, these roles were selected due to their high degree of influence over security and stability. This role play, a unique and core aspect of FP PeaceGame design, enabled participants to look at the crisis through other stakeholders’ perspectives and more deeply understand their incentives amid the changing circumstances the scenario presented. The outcomes and recommendations from the simulation can help inform real-world strategy and policy planning.

THEME OF THE SCENARIO: VENEZUELA STATE COLLAPSE

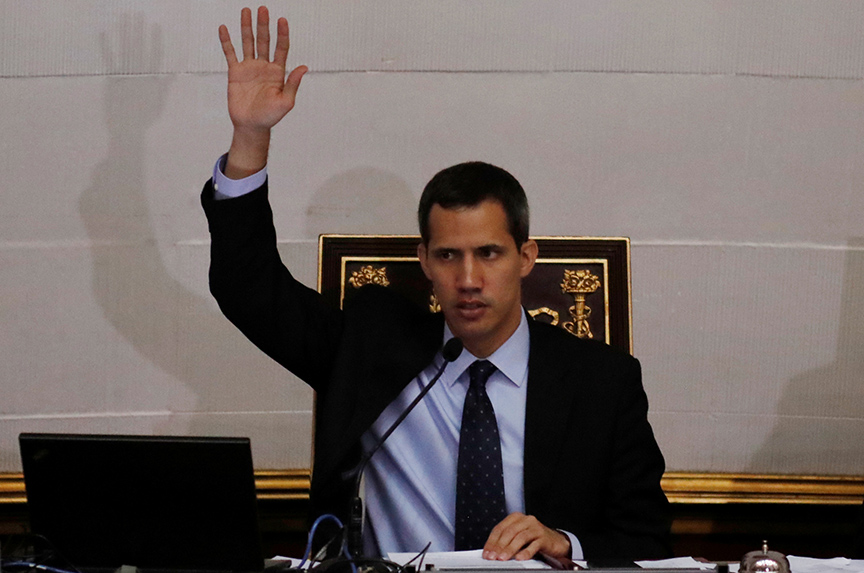

The scenario outlined a series of possible events that, if triggered, could together precipitate a near-term collapse of the Venezuelan state. While fictitious, the scenario was crafted in light of known and ongoing pressures impacting Venezuela and was designed to compel participants to think through how they would respond should such events occur. The scenario envisaged the US and Europe intensifying economic pressure on the Maduro regime by cutting off Venezuela’s ability to use international payment systems for transactions. Targeted and intensified sanctions coupled with the inability to access financial markets finally squeezed the Maduro regime to the brink, precipitating the political and economic collapse of the state and taking domestic institutions down with it. The financial embargo also limited remittance flows, exacerbating the desperation of all Venezuelans, fueling the black market, trafficking, and criminal activity inside and outside Venezuela. In the scenario, the interim government, led by Juan Guaidó, was not able to establish control amid the chaos. This all occurred against a backdrop of a broader pullback of US foreign aid to the region. Within this context, participants played out three crisis situations—exacerbating trafficking, security, and humanitarian aspects of the ongoing crisis—each presenting new challenges and producing a series of unexpected outcomes.

KEY THEMES EMERGED

- Russia and China’s unified support for the Maduro regime, and unwillingness to budge on the UN Security Council.

- The outsized role Cuba could play as an arbiter between the interim government and its allies, and the Maduro regime and its steadfast Chinese and Russians backers.

- Colombia and the US’s insistence on the importance of an international coalition behind intervention, but a general lack of broader consensus on whether or not to support military action.

- An expressed willingness on the part of Colombia and the US to take military action, but only if absolutely necessary and no such coalition could be formed.

- The rate and degree to which the US and regional allies, as well as international allies, could cede influence in the region due to inaction, creating a power vacuum for other actors to step into.

- The need to prioritize immediate aid to migrants and the need for joint civil-military action to expedite the response.

- The potential for the interim government to engage non-state actors such as the FARC and ELN as political allies and as partners in providing relief to migrants.

- Non-state actors’ (the FARC, ELN, colectivos) ability to gain power as the situation deteriorated. These groups took advantage of the power vacuum to increase their support, legitimacy, and bargaining power—including through the delivery of aid.

- The inability of the UN to respond to the devolving humanitarian crisis in a timely manner, and the need for immediate, coordinated action among governments, military, and local NGOs to provide direct aid to migrants.

MAIN TAKEAWAYS

- Despite overwhelming concern about the rapidly deteriorating conditions unfolding in the region, the actors had difficulty coordinating actions to mitigate the fallout and stabilize the situation within the time constraints imposed by the exercise. In the end, the humanitarian emergency was able to galvanize a response to the security crisis, but not before widespread civilian deaths had occurred.

- The US, Colombia, and supporters of the interim government struggled significantly more than the alliance of Russia, Cuba, and the non-state actors to mount a coordinated response. Colombia’s willingness to respond with force to the situation unfolding along its border divided its regional allies. With CARICOM and other regional allies intent on closing their borders and waiting for UN action, Colombia’s urgency and call for a military solution prevented a regional consensus from emerging—and in the end, Colombia did not initiate a military response.

Cuba and Russia stood out as influential and increasingly powerful actors in the region. Both played an outsized role in multiple moves.

- The key dispute holding back action revolved around uncertainty regarding who represented the legitimate government of Venezuela post-collapse. With Colombia and the US supporting the interim government, and China, Cuba, and Russia supporting the Maduro regime, the UN Security Council found itself in a stalemate that could not be overcome. This stalemate both contributed to a worsening humanitarian toll and increased China, Russia, and the FARC/ELN’s leverage as they capitalized on the power vacuum.

- Despite the stalemate in the UN, participants made repeated calls for UN assistance, including a peacekeeping mission and humanitarian assistance.

- While hamstringing the UN, Russia, China, and their Cuban and FARC/ ELN allies further strengthened their role, taking direct action and elevating their public positions as the only bearers of aid. The US and other actors also offered aid, with NGOs providing a critical role inside and outside Venezuela—underscoring the importance of close collaboration with and financial support of these organizations already on the ground.

- Cuba and Russia stood out as influential and increasingly powerful actors in the region. Both played an outsized role in multiple moves. Cuba’s ability to deliver medical aid placed the country at the center of negotiations with many different groups, including NGOs, governments, and non-state actors. Russia’s assets in Venezuela, presence on the UN Security Council, and ability to lend financial, military, and humanitarian aid meant that its support was crucial in determining the outcome in Venezuela—highlighting how a little money can go a long way.

- Prolonged debate within the international community and indecision on the part of the US concurrently diminished the role and influence that the US, their allies, and the interim government had in Venezuela and the region.

SIMULATION SUMMARY

The actions taken as part of each move were for illustrative purposes only.

MOVE 1: TRAFFICKING SPIKES AMID ECONOMIC COLLAPSE

Heavily armed colectivos were dispatched across major cities in an effort to establish control, but with Maduro no longer at the helm, the colectivos splintered into factions allying with varying members of the former Maduro regime accessing arsenals of weapons. Armed groups capitalized on the power vacuum, enlisting followers through terror or bribing them with food as they battled to establish control over land and air trafficking routes. These routes had become the country’s economic arteries, penetrating deep into neighboring countries and beyond. Known trafficking zones in Apure, Zulia, and Táchira states spread, channeling weapons, drugs, and gold to transit points in Central America and the Caribbean bound for US and European markets. Meanwhile, the terror and instability accelerated Venezuelan migrants’ exodus.

MAIN ACTORS’ RESPONSE

From the outset, a number of the key themes came into play. The US, Colombia, and allies of the interim government debated multiple courses of action but failed to reach a consensus. The group continually expressed a desire for the UN to lead any action in the region, despite the UN’s inability to act due to China and Russia’s ongoing support for the Maduro regime. While the rest of the world debated an intervention, the FARC and ELN took advantage of the chaotic state of affairs, leading looting missions and increasing their recruiting efforts. The colectivos moved to partner with the FARC and ELN, with the goal of taking control of all media channels in the country. This was the first step in a continual consolidation of power by non-state actors, which played out through the ensuing scenarios. The interim government sought to recruit the FARC/ELN and establish a relatively stable governing position in Maracaibo. Colombia called for a direct military intervention and looked to partner with the US to control smuggling routes, given that talks had stalled in the UN. CARICOM staunchly opposed military intervention, insisting it would make the situation worse for their countries. Despite this, the US expressed a willingness to engage militarily if there was an attack on Colombia or significant loss of civilian lives, a move that was strongly opposed by Cuba. In this respect, Cuba found itself aligned with Russian and Chinese interests, creating a coalition among these actors. While still hesitant to take sides in the conflict, the Cuban government found itself in an unexpectedly powerful negotiation position among competing parties.

MOVE 2: IRREGULAR WARFARE ERUPTS ALONG THE BORDER

The colectivos’ incursion into the border regions near Cúcuta, Colombia, triggered territorial disputes aimed at gaining control over trafficking routes. What had been isolated skirmish- es escalated and a border war erupted between Colombia and Venezuela, where guerrillas from Colombia’s ELN and the FARC were concentrated—and through which Venezuelan migrants were transiting to escape the violence. A caravan of migrants was caught in the crossfire and women and children were killed, further destabilizing the region and threatening a regional, military conflagration. An emergency meeting of the UN Security Council was called.

The US and the regional partners of Brazil, Peru, Ecuador, and Chile all demonstrated a willingness to pursue military intervention without the backing of the UN. CARICOM joined Russia, China, and Cuba in staunchly opposing military action.

MAIN ACTORS’ RESPONSE

In the second stage of the conflict, the themes that emerged in the first move became more entrenched. The UN continued to be sidelined, leading Colombia to call for support for military action from regional allies and the US. In response, the US and the regional partners of Brazil, Peru, Ecuador, and Chile all demonstrated a willingness to pursue military intervention without the backing of the UN. CARICOM joined Russia, China, and Cuba in staunchly opposing military action. Interestingly, in the face of this pushback, the US pointed to elements of the international response vis-à-vis the Syrian and Libyan conflicts that could serve as possible models for coordinated action. The US drew analogies to how the UN had been able to spur collective action in these situations and urged the rest of the global community to join them in drawing up a plan for a coordinated global response to the crisis in Venezuela. This proposal was met with resistance from the now firmly allied block of Maduro backers: Russia, China, and Cuba. Amid the increasing chaos, Peru and Ecuador closed their borders, noting that the refugees they had already accepted were facing increased xenophobia and violence, and asserting that the measure was necessary to protect those migrants who were already within their respective countries and to avoid exacerbating the situation. The colectivos continued to benefit from the situation, as the interim government heavily sought to recruit them, offering a genuine path to legitimacy in return for their support.

MOVE 3: MEASLES OUTBREAK AND CONTAGION

As the state collapsed, the health system also disintegrated. Chronic blackouts, lack of running water, and unsanitary conditions became pervasive, as are already being reported in Venezuela. The scenario unfolded with a measles outbreak in Petare, one of the poorest and most densely populated neighborhoods in Caracas where limited access to sanitation and health services compound such risks. Meanwhile, violence, hunger, and desperation accelerated migrant flows from the city, increasing Venezuela’s already historic rates of outward migration from 5,000 to an estimated 10,000 a day. The humanitarian and health situations deteriorated rapidly amid the violent and unstable paramilitary backdrop, further complicating aid delivery. The outbreak spread along migrant routes toward neighboring Colombia, Brazil, Guyana, and the Caribbean, overwhelming already taxed humanitarian capacity.

Russia, Cuba, and the Maduro regime were able to coordinate and act much more quickly and effectively, while enjoying wider support from China and the non-state actors on the ground.

MAIN ACTORS’ RESPONSE

The final moves of the scenario clearly presented the major themes of the game. Power shifted toward the Maduro regime’s supporters (China, Russia, and Cuba) and non-state actors (colectivos, the FARC, ELN). Cuba solidified its role as a regional leader as NGOs, Russia, the Maduro regime, and the colectivos all sought to coordinate with the Cuban government to distribute medical aid. These groups were able to coordinate and mobilize much more effectively than the splintered US and regional allies, who once again were unable to mount a coordinated response. While the US and Colombia prepared to lead a military intervention, regional allies were split on whether to support them. CARICOM and Brazil joined Peru and Ecuador in closing their borders, despite urging from Colombia and the US to use their health systems to support Venezuelan migrants. This divide between Colombia and the US, and the rest of the regional allies stagnated any coordinated action and put regional countries at odds with each other. The alliance among Colombia, the US, and the interim government was eager to intervene, but a lack of regional support and UN assistance put the group in a weak position. Russia, Cuba, and the Maduro regime were able to coordinate and act much more quickly and effectively, while enjoying wider support from China and the non-state actors on the ground.

RECOMMENDATIONS & NEXT STEPS

The goal of the crisis simulation and resulting dialogue was to help inform international and Venezuela-focused decision-making. The outcomes from the scenario make clear that this is an international crisis that requires immediate action. Recommendations include:

- International stakeholders who support democracy must develop a coordinated and agile action plan now that can prevent or, if collapse occurs, mitigate the very real regional and global impacts.

- Democratic forces in Venezuela must be strategic in planning how to mitigate the influence of poorly intentioned external actors who could accelerate and take advantage of state collapse.

- Understanding that additional UN aid delivery will take months to mobilize, coalition governments and local NGOs must coordinate now to identify key migrant routes and finance direct delivery of aid.

- With the intersectionality of the crisis, multiple tracks need to be pursued at once, including those aimed at stability, the distribution of aid, and a negotiated political settlement.

- Communicable disease outbreaks and contagion represent real risks, as illustrated by recent measles outbreaks in Samoa and around the world, necessitating preparation and coordination among regional health ministries and experts to respond and contain potential outbreaks.

- Contingency plans must be developed to address rapidly deteriorating security conditions, should the UN Security Council not act.

- Since island nations are among the most vulnerable to spillover effects from the crisis, multilateral development banks and regional institutions must engage to provide needed economic, humanitarian, and security assistance.