Policy memo: A NATO-style spending target could fund long-term decarbonization

SUMMARY

At the NATO 2006 Riga summit, heads of state and government made an oral pledge to spend 2 percent of their gross domestic product on defense. This moment marked a significant shift for the alliance. The United States had been effectively subsidizing European security for half a century and was intent on finding a way to both measure political will and ensure that existing and new members meaningfully contributed to the Alliance’s efforts. Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 cemented the importance of the 2 percent target for the Alliance, and at the Wales Summit of that year, leaders reaffirmed the goal of meeting the 2 percent target by 2024. Spending is done on an ad hoc basis, and the target is remarkably simple: it essentially tracks members’ defense ministry budgets, with small adjustments to account for spending that pertains to military activities that may not be under the purview of the ministries of defense. Eight years on, could Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 spark a new spending target, this time to speed up the energy transition?

In the wake of the energy crisis and the war in Ukraine, decarbonizing European economies has emerged as one of most important tools for the European Union to ensure its long-term security and sovereignty. This is true both in terms of managing catastrophic climate change-related risks and also to reduce core dependencies that threaten European independence and subsistence. So far, European member states have committed insufficient funds to meet their decarbonization objectives. Meanwhile, the European Commission estimates that an additional €700 billion of combined public and private investment is needed each year across the entire EU bloc to meet established targets for the green transition.

To help turn the tide, EU member states and like-minded allies should set national-level spending targets, each based on a percentage of the respective annual gross domestic product (GDP), to address these deficits. This would provide the basis of an international coalition that would ramp up global climate spending and set a useful benchmark to anchor high-level diplomatic discussions on the subject. Such a coalition would help ensure that these states commit to long-term investments, with consistent and predictable funds flowing to decarbonization-related areas for the foreseeable future.

Addressing the lack of a set metric for EU members’ green investments

This coalition would help Europe set its own house in order with green public investments. In recent weeks, alarm bells have rung across the continent,1See the 2023 European Climate Neutrality Observatory Flagship Report and the 2023 European Court of Auditors special report on climate and energy targets. warning that Europe is far off track: all but two EU countries (Lithuania and Czechia) have significant national spending gaps incapable of being filled by EU spending alone. Overall, the EU has made significant strides in seeing itself targets through programs like NextGenerationEU, the European Green Deal and the associated Fit for 55 package that is in the process of piecemeal ratification in the European Parliament, and the REPowerEU Plan, presented as a means of restraining Russia’s ability to use energy as a tool of extortion. It now needs the means to finance them.

One of the main deficits that has emerged in decarbonization strategies is the consistent lack of long-term and sustained climate investment spending. Even the European Commission itself has missed its own climate budget targets, such as aiming to use 20 percent of the 2014-2020 budget to fund climate activities, and later claiming it met that goal. However, a recent report from the European Court of Auditors (ECA), contradicted those claims, finding the Commission had overstated its climate commitments. Brussels can and must do better.

Meanwhile, the majority of EU members still do not invest enough in low-carbon energy systems, particularly by the standards set at the supranational level under the Fit for 55 goals and REPowerEU Plan. Consequently, most EU members are not on track to hit their carbon emission and renewable energy adoption targets under either scheme. Drawing upon the funding examples set by NATO and such a EU-led international spending coalition, this investment commitment policy could help address the ongoing issue of the lack of long-term national climate investments.

Internationally committing to spending a percentage of annual GDP on green investments would address the lack of a set metric for EU members’ long-term decarbonization investments. Prior to the announcement of the REPowerEU plan in 2022, most EU members’ long-term green investments and decarbonization commitments fell under the purview of the 1997 Kyoto Protocol and the 2016 Paris Climate Accords. Both have received criticisms for not going far enough in encouraging reductions in carbon emissions, particularly with too few penalties for lack of compliance. A new spending target would take this revolution a necessary step further.

This is crucial as all European countries need to ramp up their public spending if they are to meet their decarbonization goals. For example, Germany, as the largest EU economy, has spent approximately $92 billion toward achieving climate neutrality between 2020 and the present. Broken down annually, these expenditures would be the equivalent of about $3.1 billion, or about 0.75 percent of Germany’s annual GDP. However, McKinsey estimated in 2021 that at least €240 billion (approximately $259 billion) of total spending (both public and private) would be required annually until 2045 for Germany to achieve full decarbonization, the equivalent of 7.05 percent of Germany’s GDP per year. Current spending is nowhere near enough.

Furthermore, a climate spending target could also put positive pressure on countries that have expressed reservations about the EU-level decarbonization goals. Poland, which retains the most reliance on coal for its energy needs, is a case in point. Poland’s projected expenditures are much smaller compared to larger EU economies like Germany, and its government has publicly expressed some reservations about the Fit for 55 goals, raising some concerns from other EU members on how staunchly committed it might be on cutting carbon emissions. An international spending target could focus minds.

The EU’s neighboring countries, which are not required to hit the Fit for 55 goals or comply with REPowerEU, would benefit from joining this spending-target coalition by making commitments of their own for national-level decarbonization commitments. The United Kingdom, Switzerland, Norway, and Canada are illustrative cases as none of them maintain a single long-term national climate investment pledge, with climate and decarbonization spending committed from budget to budget. A European Union-led initiative could catalyze them into action.

Determining the proportion of GDP to use as a funding baseline

This climate spending coalition will have to come to a consensus on what percentage of their annual GDP should be a baseline for decarbonization investments. As noted previously, some countries are already much further along than others in setting a decarbonization strategy, and a named target won’t have as much of an impact on what’s already being spent. Others, which are still more reliant on more carbon-intensive energy sources like coal, will have to invest more in renewable energy systems.

Going back to the case with Europe, the European Commission itself has provided varying figures over the years on how much should be invested as a proportion of GDP. The lowest proportion of GDP that the European Commission suggested for Europe’s investments was 2.3 percent excluding transportation and infrastructure spending—first raised in 2020 during the first year of the pandemic. This limited figure is likely the easiest baseline for EU members to agree on given that it is a relatively low proportion of GDP. However, the European Commission suggested in 2022 that 3.7 percent of European GDP would need to be invested, including transportation and building-related needs, which would be politically much harder to justify.

In a recent assessment by a think tank called Agora Energiewende and the European Commission, the overall annual GDP percentage investments outside of transportation infrastructure required for hitting existing 2030 carbon emissions targets was 2.5 percent. Yet, between member states, the annual GDP percentage investments varied greatly, with estimates as high as 8.1 percent for Bulgaria and as low as 0.9 percent for Belgium.

Therefore, at an international summit with like minded allies like the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Norway, Canada and potentially the United States to discuss setting a standard for government spending on decarbonization, it might be worth providing 2.5 percent as a starting point for discussions. Coalition members should approach the target with what is politically possible in mind, such as being willing to count investment that is coal-to-gas switching, and green transport, grid, and infrastructure investment under this rubric. A proposed coefficient to decide what spending could count could be a modified version of the EU’s Climate Coefficient, which was first developed by the EU in 2021. This however, should all be up for negotiation.

What setting a spending metric achieves

An annual international GDP spending commitment for decarbonization provides a tangible metric for coalition states to follow as they continue to develop and implement decarbonization strategies. This would ensure that these states have an expenditure standard to work toward rather than playing it by ear, such as the way the REPowerEU plan was developed following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Expenditure commitments would likewise make it harder for states to backtrack on reducing carbon emissions. This is essential for progress toward decarbonization, in which states constantly made strides (e.g., joining the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Climate Accords) only to fall short on follow-through. An expenditure commitment would also provide a baseline for these states to discuss energy security burden-sharing and a spending target to work toward. Not only does the NATO spending target provide precedence but the United Nations 0.7 percent spending target for aid and development is written into law in the United Kingdom.

Some European states have already committed to impressive expenditures to reduce carbon emissions by 55 percent by 2030. The most prominent case is France, which could lead by example if it declares that it has already committed in practice to invest at least 2.5 percent of its annual GDP to reduce carbon emissions. This is the case because current French climate expenditures, when divided annually between the present and 2030, would amount to about 2.5 percent of its annual GDP. This shows that a 2.5 percent target for the international spending coalition is realistic. A powerful case could therefore be made for it at a potential summit.

However, such a spending target should not be taken as a panacea for issues surrounding decarbonization expenditures, as it is meant as a general metric and is not specifically tailored enough to each individual state’s decarbonization expenditure needs. In addition, states may struggle to actually reach the target, but it would be important to at least have it in place as an aspiration. In the case of EU members, the spending target is additionally not a replacement for existing EU climate and investment policies, like the European Green Deal and REPowerEU plan, or those of other states either. The spending is simply aimed at allowing these states to correctly fund their domestic share of the burden with the assumption that EU and other states’ industrial strategies for decarbonization will avoid overconcentration and overinvestment in certain technologies or utilities. Higher public investment also is not a substitute for private investment, which should continue to be encouraged, subsidized, and catalyzed by increased public spending.

States’ needs will vary. Countries like Poland that were more reliant on coal will likely have to allocate a significantly higher proportion of government funding to address decarbonization deficits and improve electricity grids. Meanwhile, countries which invested in greater amounts at earlier junctures, such as Finland, will face fewer struggles in forthcoming years with decarbonization. Notably, McKinsey estimates that Finland only needs to invest 0.4 percent of its GDP annually to be on the right path to slashing its carbon emissions by 55 percent by 2030.

Consequently, these countries should still seek to meet the 2.5 percent target even if they have completed decarbonization—with the funds going as grants to help poor and vulnerable countries do so or for international climate mitigation, green development assistance, and other policies.

- Develop a global coalition, led by the European Union, together with like minded allies like the United Kingdom, Switzerland, Norway, Canada and potentially the United States aimed at developing a NATO-style set GDP percentage target for annual decarbonization spending.

- Hold a summit of interested parties to discuss and agree upon this percentage spending target.

- Use the European Commission’s calculations for the minimum necessary spending for hitting 2030 carbon emissions targets of 2.5 percent of annual GDP as a starting point in discussion.

Ben Judah is director of the Transform Europe Initiative and a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center. He is the author most recently of This Is Europe and his research interests focus on the geopolitics of decarbonization, Britain and the European Union.

Francis Shin is a research assistant at the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center.

Rachel Rizzo is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center. Her research focuses on European security and the transatlantic relationship.

Théophile Pouget-Abadie is a nonresident fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Transform Europe Initiative and policy fellow at the Jain Family Institute.

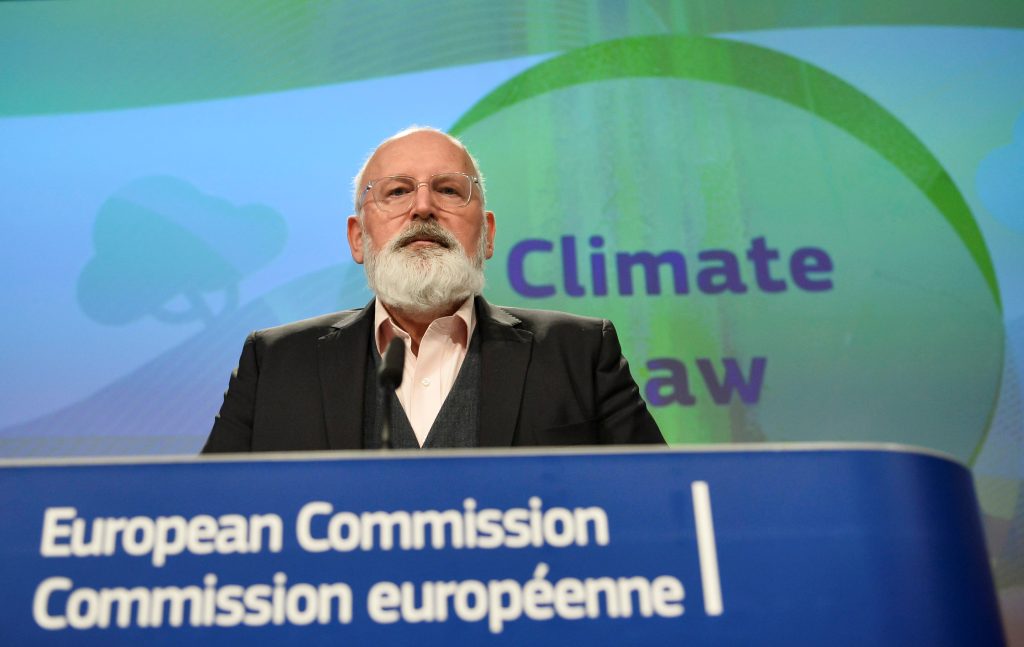

Image: In the wake of the energy crisis and the war in Ukraine, decarbonizing European economies has emerged as one of most important tools for the European Union to ensure its long-term security and sovereignty. | Unsplash