Beyond borderlands: ensuring the sovereignty of all nations of Eastern Europe

Territories between great powers—borderlands—have always been areas of strife. So it is with the countries caught between Russia and the West, those that were once part of the Soviet Union or firmly within its sphere of influence. Much of Europe has consolidated and, with the United States, established a lasting liberal democratic order, but Russia has been increasingly pushing back. Though most of the “borderlands” countries are now West-facing, Moscow wants to control at least the national security policies of its near neighbors.

The West should reject Moscow’s claim. It contradicts Western principles and is dangerous to our interests. The United States should lead the West in adopting an explicit strategy of promoting democracy, open markets, and the right of nations to choose their own foreign policy and alignments. This includes their right, if they meet the conditions, to join the EU and NATO.

Moscow has not hidden its objectives—to grow its sphere of influence; shift the post-Cold War security order; and weaken NATO, the EU, and transatlantic ties—and is applying a full spectrum of methods to achieve them. The combination of these tactics is sometimes called hybrid war. This includes strengthening ethnic ties abroad and utilizing religion, disinformation, economic boycotts, energy cutoffs, corruption, and the strategic use of its intelligence services.

Western powers have been slow to recognize the challenge posed by Russian President Vladimir Putin’s belligerent foreign policy. There was little criticism of Moscow for the 2007 cyberattack on Estonia; deferring to Kremlin sensitivities, NATO did not offer Georgia a Membership Action Plan at its 2008 summit; and when Moscow’s war against Georgia followed months later, the West levied weak sanctions on Russia and lifted them quickly. The West’s sanctions on Moscow for annexing Crimea were also weak.

NATO was slow to recognize Moscow’s challenge to the alliance. While the 2014 NATO summit did make arrangements for a rapid deployment force, it spoke of the need to “reassure” its easternmost allies rather than to deter the Kremlin. Only in 2016 did NATO decide to put battalions into the Baltic states, Poland, and Romania to dissuade the Kremlin from provocations there. With the deployment of these forces, NATO has done much to secure its eastern flank. But more needs to be done.

Contents

Executive summary & introduction

Borderlands and their discontents

The Western response to Kremlin revisionism

- The need for a clear Western policy

- Security assistance in the short and medium terms

- Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Belarus

Executive summary & introduction

To endure and succeed, a nation’s foreign policy must advance its interests and reflect its values. After World War II, US statesmen and their European partners built an international order based on principles that promoted liberty and provided a basis for economic growth. The institutions that made this possible included the United Nations, the European Union (and its predecessors), the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (which became the World Trade Organization). To defend this liberal order from the aggressive designs of the Soviet Union, Western statesmen created NATO.

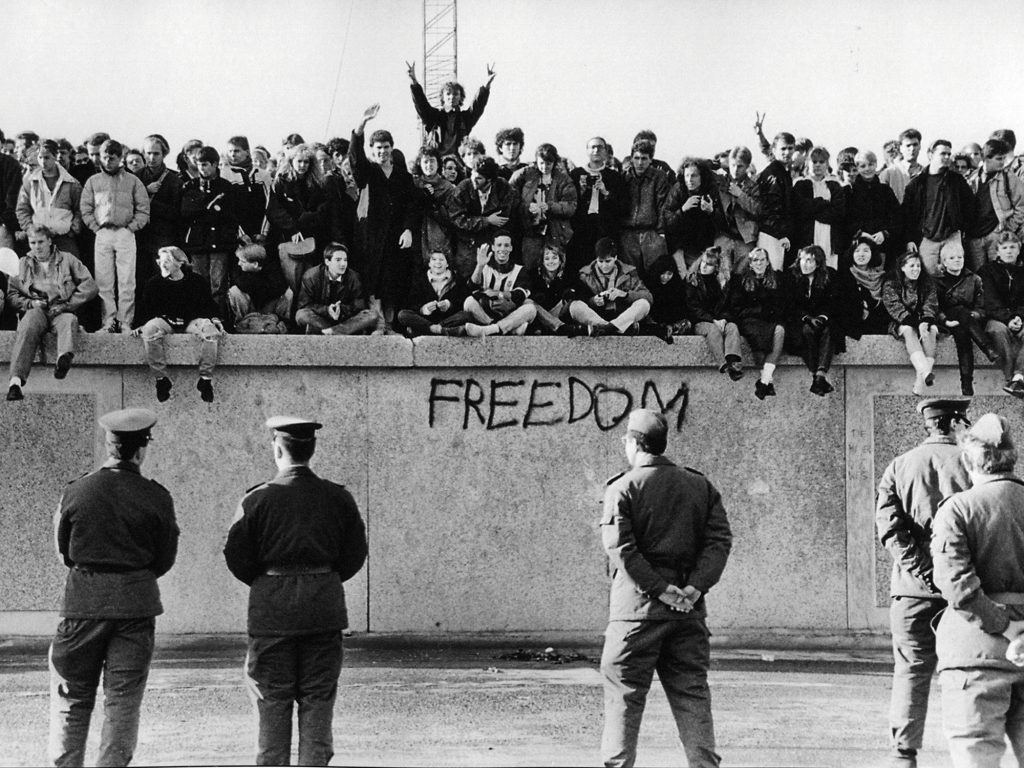

The success of these policies was historic. The European continent, which had launched two world wars in the space of twenty-five years, experienced no hot war for more than fifty years (with the exception of Greek-Turkish fighting in Cyprus). Security and stability in Europe, coupled with free-market economic policies, provided a basis for strong economic growth, and the great danger posed by a hostile Soviet Union vanished as that nation imploded in 1991.

Western policymakers, particularly those in the United States, reacted to the end of the Cold War by applying the same liberal principles to the nations that emerged from the Soviet rubble. They developed programs to help these nations transform from authoritarianism to democracy, and to build a market economy. They sponsored these countries’ memberships in key Western political and economic institutions. And, in visionary moments, these policymakers proclaimed a desire to create a Europe “whole and free,” from the Bay of Biscay to Vladivostok or, including North America, from Vancouver to Vladivostok.

The policies that the West pursued regarding the Soviet Union during the Cold War formed a kind of grand strategy, but no formal strategy toward Russia replaced it at the end of the Cold War. Although there was much discussion in foreign policy journals about the need for a new, overarching concept to replace “containment,” none appeared.

In the first post-Cold War decade, this policy seemed to face no real opposition. The former nations of the Soviet empire were expected to share the vision. That included Russia, which, under President Boris Yeltsin, was a developing democracy.

This began to change after President Vladimir Putin took power in 2000. In his first year in office, Putin took control of the major television stations; from there, he moved the country in an authoritarian direction—or, as he likes to say, toward a “managed democracy.” He also began to push back against the concept of a liberal international order and the right of nations that had once been part of the Soviet Union, or even the broader Soviet empire, to make their own national security decisions, particularly decisions to join NATO, or even the EU. Significantly, Russian pushback included wars in Georgia and Ukraine that changed the map of Europe, and regular provocations against the Baltic states.

The Kremlin’s hostile policies were a direct rebuke of the vision of a Europe whole and free. Instead of a unified Europe, the Kremlin presented a vision of itself as a unique civilization, and as a center of power with Europe to its west and China to its east. Moscow further insisted on its right to control the policies of its near neighbors in the borderlands, commonly known in Russia as the “Near Abroad,” between itself and Europe.

Moscow’s new belligerence gave Western leaders pause. This was evident even before Moscow’s August 2008 attack on Georgia. At the NATO Bucharest Summit in the spring of 2008, US efforts to establish a Membership Action Plan for Georgia and Ukraine failed in the face of Germany, France, and others’ reluctance to “provoke” Putin.1David Brunnstrom and Susan Cornwell, “NATO Promises Ukraine, Georgia Entry One Day,” Reuters, April 3, 2008, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-nato/nato-promises-ukraine-georgia-entry-one-day-idUSL0179714620080403. That was a mistake, as the decision instead emboldened the Kremlin to go to war against Georgia months later.

The thesis of this paper flows from this logic.

Kremlin opposition to the notion of a Europe whole and free has given new life to the old concept of borderlands, the territory between large independent powers. Moscow argues that the West should cede to its dictates to control at least the national security policies of its near neighbors.

The West should reject Moscow’s claim. It contradicts Western principles and is dangerous to Western interests. The US should lead the West in adopting an explicit strategy of promoting democracy, an open society and open markets throughout Europe and Eurasia, as well as the right of nations in this area to choose their own foreign policy and alignments. This includes their right, if they meet the conditions, to join the EU and NATO.

Advocates of accommodating Moscow think they are buying peace and stability. That is an illusion. Such accommodation makes the borderlands places of Kremlin aggression and instability. While the West accepts Kremlin control under this option, there is no reason to assume that the people of these regions are willing to forfeit their futures to autocrats in Moscow. So, Western principles and interests would be served by policies that back the aspirations of the nations in these areas to determine their own futures. The likely result would be the erasing of the borderlands, and the creation of a Europe whole and free.

Borderlands and their discontents

Territories between great powers—borderlands—have historically been areas of strife. In antiquity, the Roman Empire fought repeatedly with first the Parthian Empire, and then the Sasanian Empire, over Armenia, Syria, and Mesopotamia. In the nineteenth century, the British Raj in India and an expanding Russian Empire in Central Asia competed in the “Great Game” for influence in Afghanistan. In early twentieth-century Europe, imperial rivalries and ethnic ambitions provided the spark that ignited World War I. The infamous Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in August of 1939 erased the borderlands in East and Central Europe as the Soviets seized the eastern half and the Nazis the western half. World War II began nine days after its signing.

World War II ended in Europe as US and British forces from the west, and Soviet forces from the east, converged on Germany. The post-World War II order in Europe was hammered out in the great conferences at Yalta and Potsdam. In these gatherings, the Western powers initially insisted on the right of people to choose their own governments and futures; some documents signed by all parties, like the Declaration of a Liberated Europe, gave voice to these principles.2Yalta Conference, “Section II – Declaration of a Liberated Europe,” February 1945, http://avalon.law.yale.edu/wwii/yalta.asp. But, with Soviet forces on the ground throughout Eastern Europe and no Western willingness to confront them, there was little prospect that truly independent nations would emerge there—and they did not.

As the euphoria of defeating Adolf Hitler gave way to the realities of the Cold War, the nations of Western Europe banded together with the United States and Canada to create the defensive NATO alliance to deter Soviet aggression. To shore up European stability during that period, the United States also provided billions of dollars of aid under the Marshall Plan. But, to forestall US influence In Eastern Europe, the Soviets persuaded their allies not to seek Marshall Plan support. In response to the establishment of NATO, the Soviet Union created the Warsaw Pact and insisted that the nations of Eastern Europe become members.

The result was that, in the years following World War II, two opposing camps emerged in Europe—with no intervening territory. In the north, NATO member Norway bordered the Soviet Union. On the southern end, Turkey anchored NATO, and likewise shared a border with the Soviet Union. In the heart of Europe, NATO nations bordered Warsaw Pact nations. In the middle was Austria, which was officially neutral, by the treaty under which Soviet forces left the country.

The post-Cold War security order

The collapse of the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact changed all of this. Fifteen independent nations emerged from the Soviet Union: Russia, the three Baltic states, the five Central Asian states, the three states of the Caucasus, and Belarus, Moldova, and Ukraine. Moscow’s six Warsaw Pact allies—Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary, Poland, Romania—also found themselves truly independent. East Germany joined a united Germany and Czechoslovakia split into the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Yugoslavia, a socialist state that never joined the Warsaw Pact, fractured violently into seven new states: Bosnia, Croatia, Kosovo, Montenegro, the Republic of Macedonia, Serbia, and Slovenia.

Post-Cold War Europe and Eurasia established a new security order. The Helsinki Final Act, which was signed in 1975,3US Department of State Office of the Historian, “Helsinki Final Act, 1975,” https://history.state.gov/milestones/1969-1976/helsinki. served as the basis for this new order. The Charter of Paris (1990) ratified these principles.4OECD, “Charter of Paris for a New Europe,” November 21, 1990, https://www.osce.org/mc/39516. The most important are

- the sovereignty and territorial integrity of states;

- the right of states to choose their own political and economic systems, and their own foreign policy and security arrangements;

- the peaceful settlement of disputes among states by negotiations, and in accordance with international law; and

- the inadmissibility of resolving interstate disputes by war.

These principles were designed to provide security and freedom to all of the states of Europe and Eurasia. Consistent with them, the three Baltic states chose to join NATO and the EU. Ten other states joined NATO, and eight the EU.

These developments were also consistent with the vision of Western statesmen to integrate the nations that came out of the Soviet Empire, including Russia, into the liberal institutions created in the years after World War II—the UN, the IMF, the World Bank and the World Trade Organization. That vision also included creating a Europe whole and free.

By most measures, the security order created after the fall of the Soviet Union has been a great success. Despite the myriad security challenges that have arisen—global terrorism, chaos in the Middle East, North Korea’s nuclear program—the past quarter century has avoided war between major powers, and the accompanying economic ruin and loss of life. Today, less than 10 percent of the world’s population lives in extreme poverty.5Adam Taylor, “For the First Time, Less than 10 Percent of the World Is Living in Extreme Poverty, World Bank Says,” Washington Post, October 5, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2015/10/05/for-the-first-time-less-than-10-percent-of-the-world-is-living-in-extreme-poverty-world-bank-says/?utm_term=.f664a201a0ca. At the end of World War II, that number was more than 70 percent.

The benefits of this post-Cold War world have been evident In Europe. All of the nations that joined the EU and NATO have established working democracies and made great economic progress. Poland, for instance, currently enjoys a GDP per-capita purchasing parity power (PPP) of $27,216.44 USD, up from $9,521.78 in 1991.6Trading Economics, “Poland GDP per Capita PPP 1990-2018,” https://tradingeconomics.com/poland/gdp-per-capita-ppp. Bulgaria has seen an increase of more than 50 percent in GDP per-capita PPP, sitting at $8,311.93 from an average of $4,992.74 between 1980 and 2017.7Trading Economics, “Bulgaria GDP per Capita 1980-2018,” https://tradingeconomics.com/bulgaria/gdp-per-capita. In the Baltics, Estonia has seen similar improvements, with GDP per-capita PPP reaching $18,977.39 from a low of $7,313.74 in 1995. 8Trading Economics, “Estonia GDP per Capita 1995-2018,” https://tradingeconomics.com/estonia/gdp-per-capita. The current problems facing the continent—such as the immigration crisis and Brexit—are partly a result of the economic boom that it has enjoyed over the past quarter century.

A revisionist Russia emerges

Yet, every silver lining has its cloud; in this case, the cloud began to gather over Moscow. In the 1990s, a newly independent Russia moved in the direction of democracy, and sought help from the West in transforming its economy. Despite some complaints about NATO enlargement and NATO’s policies in the Bosnia and Kosovo crises, Moscow did not push back hard against the West’s vision of a liberal, democratic Europe.

This began to change after Putin succeeded Yeltsin as president of Russia. In his first years as president, Putin maintained Yeltsin’s policies of basic cooperation with the West, and focused on paying off Russia’s foreign debt, which he saw as a national security liability. With the sharp rise in the price of oil and gas—Russia’s major export products—in the early 2000s, Russia prospered as never before.9Dr. Sergey Aleksashenko, The Russian Economy: Short-Term Resilience, Long-Term Stagnation (Washington, DC: Atlantic Council, 2018), http://www.atlanticcouncil.org/publications/issue-briefs/the-russian-economy-short-term-resilience-long-term-stagnation. But, even as cooperation with the West continued, Putin asserted Russia’s privileged status in its neighborhood, the Near Abroad; his first trip as president was to neighboring Uzbekistan. 10Timur Abdullaev, “Uzbekistan Maneuvers,” Perspective vol. 14, no. 4, June/July, 2004, https://www.bu.edu/iscip/vol14/Abdullaev.html.

Significantly, Putin began to act immediately to consolidate his power, at the expense of Russian democracy. In his first year in office, Putin took control of Russia’s major television stations from their oligarch owners. In ensuing years, he curbed the political activities of oligarchs (such as the arrest of Mikhail Khodorkovsky), replaced elected regional governors with appointees, reduced the legal space for opposition activities, and used the politically controlled justice system against potentially dangerous rivals such as Alexander Navalny.11Masha Gessen, “The Wrath of Putin,” Vanity Fair, January 30, 2015, https://www.vanityfair.com/news/politics/2012/04/vladimir-putin-mikhail-khodorkovsky-russia; “Russian Duma Backs Putin Reforms,” BBC, October 29, 2004, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/3965845.stm; Ann M. Simmons, “Vladimir Putin’s 18 Years in Power—the Highs and Lows, and Don’t Forget the Shirtless Pics,” Los Angeles Times, March 19, 2018, http://www.latimes.com/world/europe/la-fg-vladimir-putin-timeline-20180319-story.html; “Alexei Navalny: Russia’s Vociferous Putin Critic,” BBC, March 15, 2018, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-16057045. In addition, there were the unsolved murders of opposition figures like journalist Anna Politkovskaya, who reported critically on the Russian war in Chechnya, in 2006, and politician Boris Nemtsov in 2015.12Shaun Walker, “The Murder That Killed Free Media in Russia,” Guardian, October 5, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/oct/05/ten-years-putin-press-kremlin-grip-russia-media-tightens; Andrew E. Kramer, “Boris Nemtsov, Putin Foe, Is Shot Dead in Shadow of Kremlin,” New York Times, February 27, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/28/world/europe/boris-nemtsov-russian-opposition-leader-is-shot-dead.html.

But, even as cooperation with the West continued, Putin asserted Russia’s privileged status in its neighborhood, the Near Abroad

As Russia turned authoritarian and its economy boomed, Moscow began to practice a more assertive foreign policy. The flashpoints were first what Moscow calls “colored revolutions,” the rising of citizens against authoritarian rulers. The Kremlin claimed that these political uprisings were Western-organized coup d’etats against elected leaders.13Darya Korsunskaya, “Putin Says Russia Must Prevent ‘Color Revolution,’” Reuters, November 20, 2014, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-russia-putin-security/putin-says-russia-must-prevent-color-revolution-idUSKCN0J41J620141120. It watched unhappily as authoritarian rulers were tossed out in Serbia in 2000 and Georgia in 2003.14“Milosovic Extradited,” Guardian, June 29, 2001, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2001/jun/29/warcrimes.guardianleaders; Tina Tsomaia, “Georgia’s Rose Revolution,” Foreign Policy, October 23, 2009, https://foreignpolicy.com/2009/10/23/georgias-rose-revolution/. Moscow strove mightily to ensure that President Leonid Kuchma in Kyiv would be succeeded by Russia-friendly Viktor Yanukovych in 2004.15William Schneider, “Ukraine’s ‘Orange Revolution,’” The Atlantic, December 14, 2004, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2004/12/ukraines-orange-revolution/305157/. But, its efforts failed, as the Ukrainian authorities’ efforts to seal that election sparked the Orange Revolution, which ensured another round of voting won by Viktor Yushchenko, an ally of the West.

To the Kremlin, the upheavals in Serbia, Georgia, and Ukraine were not domestically driven, but the creation of the West—especially the United States. By the February 2007 Munich Security Conference—after six strong years of economic growth, two rounds of NATO enlargement, and the Orange Revolution in Ukraine—Putin delivered a speech laying out the anti-Western animus of his policy, and his frankly revisionist aims.16Ian Traynor, “Putin Hits at US for Triggering Arms Race,” Guardian, February 10, 2007, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2007/feb/11/usa.russia. Those aims included

- a sphere of influence for Russia that matched the territory of the former Soviet Union;

- changing the post-Cold War security order; and

- weakening NATO, the EU, and transatlantic ties.

Moscow has not been shy in pursuing these aims. In the summer of 2007, angry that Estonian officials had decided to relocate a monument to Soviet “liberators” of Estonia from Nazi rule, the Kremlin launched a cyberattack that shut down numerous services in the country.17Ian Traynor, “Russia Accused of Unleashing Cyberwar to Disable Estonia,” Guardian, May 16, 2007, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2007/may/17/topstories3.russia. This was followed by Moscow’s war on Georgia in 2008, and its recognition of the “independence” of South Ossetia and Abkhazia.18Associated Press, “A Scripted War,” The Economist, August 14, 2008, https://www.economist.com/briefing/2008/08/14/a-scripted-war. In 2014, after months of demonstrations sent Ukrainian president Yanukovych packing, the Kremlin seized and “annexed” Crimea, and began its not-quite-covert, hybrid war in the Donbas.19Vladislav Inozemtsev, “There’ll Be No End to the War between Russia and Ukraine While It Suits Their Political Elites to Keep Fighting,” Independent, August 29, 2018, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/long_reads/russia-ukraine-war-putin-leaders-crimea-militia-recognise-kremlin-kiev-diplomacy-nato-us-trump-a8501301.html.

Moscow has not hidden its revisionist objectives. Instead, Putin and other senior Russian officials loudly proclaim them. In 2008, President Dmitry Medvedev said, “Russia, like other countries in the world, has regions where it has privileged interests. These are regions where countries with which we have friendly relations are located.”20Paul Reynolds, “New Russian World Order: The Five Principles,” BBC, September 1, 2008, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/7591610.stm. He added, “It is the border region, but not only.” At the 11th Valdai Discussion Club Conference in Russia in 2015, at which Putin and many other senior Russian officials spoke, the theme was “new rules or no rules.”21Vladimir Putin, “Meeting Of the Valdai International Discussion Club,” October 24, 2014, Kremlin website, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/46860.

The Kremlin Challenge

Moscow is applying a full spectrum of methods to achieve these objectives. The combination of these tactics is sometimes called hybrid war. An explanation of some of these tactics follows.

- It starts with Russian soft power. Moscow claims the right to protect ethnic Russians, and even Russian speakers, abroad. It uses alleged abuses against both groups to justify interventions in Moldova, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Estonia, Latvia, and elsewhere. At the softer end of this policy, the Kremlin has created the concept of Russkiy Mir, or the “Russian world,” to attract support for its policies from Russian communities abroad. A harder edge to this policy includes the distribution of Russian passports in Ukraine, Georgia, Moldova, and Kazakhstan, in order for Russia to be in a position to make claims against those governments on behalf of its citizens.

- Religion is a distinct part of Russian soft power. The Russian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) was reestablished by Joseph Stalin during World War II, and was a witting agent of Soviet aims.22Ksenia Luchenko, “Why Do the Russians Trust the Church Set up by the KGB?” Newsweek, February 10, 2018, https://www.newsweek.com/why-do-russians-trust-church-set-kgb-802635. The demise of the Soviet Union and the emergence of an independent Russia did not free the Moscow Patriarchate (MP) from state control. The MP has parishes throughout Ukraine, Belarus, and Moldova, and in the Baltic states.23“Ecumenical Patriarchate Agrees To Recognize Independence Of Ukrainian Church,” RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty, October 12, 2018, https://www.rferl.org/a/constantinople-patriarchate-agrees-to-recognize-independence-of-ukrainian-orthodox-church/29538590.html. Its parishes in Ukraine, for instance, provided a platform for opposing the Orange Revolution and the Revolution of Dignity. The MP has also tried to build opposition to pro-Western policies by highlighting social issues—such as LGBT rights—that are associated with the EU and the United States.24Nikita Sleptcov, “Political Homophobia as a State Strategy in Russia,” Journal of Global Iniatitives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective vol. 12, no. 1, January 2018, p. 143, https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1234&context=jgi. Indeed, with the Ukrainian Orthodox Church just recently winning its bid to the Patriarch of Constantinople for autocephaly, this lingering vestige of Russian dominion is now off the board, and represents a major step on Ukraine’s path toward the West.25“Ecumenical Patriarchate Agrees to Recognize Independence of Ukrainian Church.” The granting of autocephaly by Constantinople may mean the loss of a good number of Russian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate) parishes in Ukraine, allowing the Ukrainian Church to emerge as a rival to the Russian Church in size and influence.26Taras Kuzio, Why Independence for Ukraine’s Orthodox Church Is an Earthquake for Putin (Washington, DC: Atlantic Council, 2018), http://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/why-independence-for-ukraine-s-orthodox-church-is-an-earthquake-for-putin.

- Disinformation is perhaps the most well-known aspect of Russian soft power. Over the past decade, Moscow has sought to perfect the art of information warfare. It has devoted extensive resources to outward-focused media like the television station Russia Today and the news agency Sputnik, and to social media. It has pioneered the use of postmodern theory that denies any sort of objective truth to undercut straightforward reporting about, for instance, the shooting down of the Malaysian airliner by a Russian Buk missile over the war zone in Donbas in July 2014. Moscow has experimented with computer bots to suggest that there is massive support for its particular memes, and to promote strife in target countries.27Alina Polyakova, Here’s Why You Should Worry About Russian Propaganda (Washington, DC: Atlantic Council, 2017), http://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/here-s-why-you-should-worry-about-russian-propaganda.

- Despite its complaints about Western sanctions, Moscow has been quick to punish its neighbors with boycotts when they pursue policies that displease it. As Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine came close to concluding individual trade deals with the EU, Moscow imposed major bans on the sale of their goods in Russia.

- The Kremlin has made energy a particularly important instrument for exerting influence over its neighbors. To the extent possible, it would like to be a monopoly supplier of gas to its neighbors, and to gain control over their gas infrastructure. Here, Moscow’s instrument is the state gas company Gazprom. Gazprom cut off the supply of gas to Ukraine in the winters of 2004-2005 and 2008-2009, to demonstrate dissatisfaction with Kyiv’s Western-oriented policies.28“Gazprom Cuts off Ukraine’s Gas Supply,” CNN, January 1, 2009, http://edition.cnn.com/2009/WORLD/europe/01/01/russia.ukraine.gas/. It did the same with Belarus, to encourage Gazprom’s purchase of Belarus’ gas pipeline. Moscow’s plans to build the Nord Stream II pipeline would greatly enhance its leverage over Belarus and Ukraine. Nord Stream I is not currently filled to capacity; Nord Stream II would give Moscow the chance to redirect the flow of gas away from Ukraine and Belarus.

- Moscow also makes extensive use of corruption as a means of control. Given the prevalence of kleptocracy in Russia, this tactic is partly the export of a local practice. Moscow understands that corrupt officials are easier to blackmail. For much of the 1990s and 2000s, major gas deals between Ukraine and Russia took place between the shadowy intermediaries EuroTransGas and RosUkrEnergo.29It’s a Gas – Funny Business in the Turkmen-Ukraine Gas Trade (Washington, DC: Global Witness, 2006), https://www.globalwitness.org/documents/17837/its_a_gas.pdf. These intermediaries made it easy to divert a generous portion of the deals’ value to senior privileged insiders in Russia and Ukraine. One of these insiders, Dmytro Firtash, who is currently in Austria and under an extradition order from the United States, has been a major funder of pro-Russian activities in Ukraine.30Eric Reguly, “The Rise and Fall of Ukrainian Oligarch Dmitry Firtash,” Globe and Mail, May 12, 2018, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/international-business/european-business/the-rise-and-fall-of-ukrainian-oligarch-dmitry-firtash/article18067412/. Moscow has also taken advantage of corrupt banks in Moldova and corrupt customs officials in Odesa to launder money and export black-market arms.

- Moscow’s intelligence services, the Federal Bureau of Security (FSB) and military intelligence (GRU), also play major roles in Russian influence operations.31Andrew Roth, “How the GRU Spy Agency Targets the West, from Cyberspace to Salisbury,” Guardian, August 6, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/aug/06/the-gru-the-russian-intelligence-agency-behind-the-headlines. Their role is to infiltrate and undermine the security organs of neighboring states. Given longstanding connections between the security services, and the low wages and absence of professionalism in the target countries’ security organs, Moscow has enjoyed some success here. One of the main reasons Moscow was able to grab control of Donetsk and Luhansk in the spring of 2014 was because the local State Security Service and Ministry of Interior chiefs had been suborned by the FSB.

With the deployment of these forces to the East, NATO has done much to secure its eastern flank. But more needs to be done.

- The FSB and GRU are also responsible for kinetic operations short of war. These include assassinations of effective Ukrainian military officers far from the front in the Donbas, or Russian dissidents living in Ukraine.32Jim Heintz, “What’s GRU? A Look at Russia’s Shadowy Military Spies,” Associated Press, September 6, 2018, https://www.apnews.com/c91253cf51b446059c360157aa00754e. They also include efforts to provoke ethnic strife—for instance, in the 2017 operation that set off bombs at the Polish consulate in Lutsk.33Saim Saeed, “Polish Consulate in Ukraine Attacked with Grenade Launcher,” Politico, March 29, 2017, https://www.politico.eu/article/polish-consulate-in-ukraine-attacked-with-grenade-launcher/. Russian intelligence services have tried to raise armed revolts in other parts of Ukraine, such as the plot to establish an Odesa People’s Republic and a Bessarabian People’s Republic in the spring of 2015.34“Ukrainian MP Was in 2015 Set to Take Lead of ‘Bessarabian People’s Republic’—SBU Chief,” UNIAN, October 9, 2018, https://www.unian.info/politics/10292343-ukrainian-mp-was-in-2015-set-to-take-lead-of-bessarabian-people-s-republic-sbu-chief.html. In a 2016 effort to stop Montenegro from joining NATO, Moscow’s intelligence services organized an unsuccessful coup.35Petar Komnenic, Ivana Sekularac, and Raissa Kasolowsky, “Montenegro Begins Trial of Alleged Pro-Russian Coup Plotters,” Reuters, July 19, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-montenegro-election-trial/montenegro-begins-trial-of-alleged-pro-russian-coup-plotters-idUSKBN1A413F. To prevent an end to the “naming crisis” between the Republic of Macedonia and Greece this year, which could pave the way for Skopje’s entering NATO, the Kremlin conducted covert operations that jeopardized its relations with both countries.36Samuel Osborne, “US Warns Russia over Interference in Macedonia Referendum on Changing Name,” Independent, September 17, 2018, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/macedonia-name-referendum-russia-us-meddling-james-mattis-nato-eu-a8541136.html.

- Moscow has also used the intelligence services and criminal networks to conduct cyber operations. NATO recognized that this was a problem when Moscow launched a major cyberattack on Estonia in the summer of 2007.37Traynor, “Russia Accused of Unleashing Cyberwar to Disable Estonia.” Since the start of its war on Ukraine, Moscow has used cyber instruments to shut down electricity grids.38“Ukraine Power Cut ‘was Cyber-attack,’” BBC, January 11, 2017, https://www.bbc.com/news/technology-38573074.

The Western response to Kremlin revisionism

The major Western powers have been slow to recognize the challenge posed by Putin’s increasingly aggressive foreign policy. Indeed, some have understood Kremlin unhappiness with the growing appeal of both NATO and the EU to the unattached countries on Russia’s periphery and in the Balkans. Those powers have advocated for policies designed to prevent further accessions to those organizations. Indeed, some prominent politicians in Europe have recently criticized EU plans for a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA) with Ukraine, as that agreement ostensibly provoked the crisis that led to Moscow’s war on Ukraine.39Anushka Asthana, “Boris Johnson: Cameron Can’t Cut Immigration and Stay in EU,” Guardian, May 9, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/may/09/boris-johnson-cameron-cant-cut-immigration-and-stay-in-eu.

There was little criticism of Moscow for the cyberattack on Estonia. Deferring to Kremlin sensitivities, NATO did not offer Georgia a Membership Action Plan at its April 2008 summit and, when Moscow’s war against Georgia followed months later, the West levied weak sanctions on Russia and lifted them quickly.40Hélène Mulholland, “David Cameron Calls for Tough EU Sanctions on Russia,” Guardian, September 1, 2008, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2008/sep/01/foreignpolicy.conservatives. The West’s sanctions on Moscow for taking and “annexing” Crimea were also not stiff. Even the start of Moscow’s hybrid war in the Donbas elicited no strong sanctions from the EU, until after the shooting down of the Malaysian civilian airliner in July 2014.41Julian Borger, Alec Luhn, and Richard Norton-Taylor, “EU Announces Further Sanctions on Russia after Downing of MH17,” Guardian, July 22, 2014, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jul/22/eu-plans-further-sanctions-russia-putin-mh17.

NATO was also slow to recognize Moscow’s revisionist challenge to the alliance. While the September 2014 NATO summit made arrangements for a rapid-deployment force, it spoke of the need to “reassure” its easternmost allies, rather than to deter the Kremlin.42Oren Dorell, “NATO’s New ‘Spearhead’ Force Aims to Reassure Allies,” USA Today, September 6, 2014, https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/world/2014/09/05/nato-spearhead-force-for-aiding-allies/15132141/. Only in 2015 did NATO decide to put well-armed battalions into the Baltic states, Poland, and Romania to dissuade the Kremlin from provocations there.43“Securing the Nordic-Baltic Region,” NATO Review, April 3, 2015, https://www.nato.int/docu/review/2016/also-in-2016/security-baltic-defense-nato/EN/index.htm. This presence was ratified at the July 2016 NATO summit, which also recognized the need to deter Moscow.44Robin Emmott, Wiktor Szary, Paul Taylor, Yeganeh Torbati, Justyna Pawlak, Gabriela Baczynska, and Sabine Siebold, “Factbox: Main Decisions of NATO’s Warsaw Summit,” Reuters, July 9, 2016, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-nato-summit-decisions-factbox-idUSKCN0ZP0MX.

With the deployment of these forces, NATO has done much to secure its eastern flank, but more needs to be done. Kremlin policy in the borderlands is a constant menace to the people of this area, and a danger to Europe. Unlike the West, Moscow does not seem to have the soft power necessary to attract its neighbors and forge closer relations. So its methods are coercive, ranging the full spectrum listed above, from disinformation to war.

The people of these countries are not willing to mortgage their futures to Kremlin imperial ambitions. As a consequence, a Western policy that attempts to mollify Moscow by sacrificing the interests and hopes of the people in the borderlands will not produce peace and stability. The notion that the West can buy peace by allowing Moscow to manage its neighbors—to exercise hegemony in its sphere of influence—is completely wrong. Indeed, the history of the past fifteen years demonstrates this. The Kremlin’s war on Tbilisi and Kyiv has not dissuaded either capital from its Westward course. The same is true of Moscow’s various coercive efforts to push Chisinau away from closer relations with the EU.

The need for a clear Western policy

All of this points to the need for a new approach, but one based on an older idea—one established at the end of the Cold War. As noted above, the Charter of Paris, building on the Helsinki Final Act, set up principles for a safe and secure international order. States are sovereign; they should enjoy territorial integrity and the right to choose their own political and economic systems. They should also enjoy the right to choose their international friends and allies.

In the 1990s, the EU, NATO, and the United States embraced these principles and built their policies around them. They offered assistance to all the countries that emerged from Soviet ruins and were aiming to transition to an open society, including Russia. They boldly proclaimed their vision of an undivided Europe, whole and free. And, while not missionizing, they considered the sovereign choices of those nations from the post-Soviet world that sought admission to NATO and the EU. As those applicant nations met the standards set, they became members.

This clear policy reflected Western principles and interests, then and now. The West needs to return to this, explicitly and with confidence. The United States should take the lead within NATO in laying out this vision and reminding the allies that, at the Bucharest Summit in 2008, the door to eventual NATO membership was left open to Ukraine and Georgia. The recent accession of Montenegro and the prospective accession of the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, soon to be renamed Republic of Northern Macedonia—both actively opposed by Moscow—are recent precedents for this policy.45Associated Press, “Greece, Macedonia Say New Name of Balkan Country is ‘Republic of Northern Macedonia,’” Associated Press, June 12, 2018, http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/nationworld/ct-republic-northern-macedonia-20180612-story.html.

But, the NATO accession process must change to take account of the hostile environment that Moscow has created. In the 1990s, NATO established the Membership Action Plan as a way station for eventual membership in the Alliance. With Moscow actively opposing membership for new countries, NATO’s granting of a Membership Action Plan for a candidate country makes it a target of the Kremlin, without conferring on it the protection that membership in the Alliance offers. This was clear with Moscow’s failed coup in Montenegro in the fall of 2016.

NATO and the EU should also maintain and enhance policies designed to help the countries of the borderlands to strengthen domestic vulnerabilities that the Kremlin has exploited to promote its influence.

NATO should be willing to consider new criteria for membership. It should consider the NATO-Georgia Commission and its annual national plans as models for membership. As part of this reconsideration, NATO should clarify that possible membership cannot be blocked by Kremlin aggression or occupation.

This means that the Russian “projects” in Abkhazia and South Ossetia in Georgia—and in Luhansk, Donetsk, and Crimea in Ukraine—are not hindrances to either country joining the alliance. Of course, Article 5 security guarantees would not cover the occupied territories in either country, if and when they join NATO. There is precedent for this; West Germany joined the Alliance in 1955 without withdrawing its claim to East Germany.

The EU, too, must be clear on membership for its eastern neighbors. To its credit, the EU did not step away from the DCFTA after Russian aggression against Ukraine began, despite timid voices in the West blaming the EU for the “Ukraine crisis.”46Charles Grant, “Is the EU to Blame for the Crisis in Ukraine?” Centre for European Reform, June 01, 2016, https://www.cer.eu/insights/eu-blame-crisis-ukraine. Nor did the EU step back from its Eastern Partnership program.

Given the current turmoil in the EU over Brexit, immigration, and other issues, it would be too much to expect the organization to enunciate a clear policy outlining the path to membership for Georgia, Moldova, and Ukraine, as well as other countries. But, the EU can avoid public statements that would restrict future membership as it works out its current problems and manages its wide, and complex, relationships.

In the meantime, the EU should fully develop opportunities for greater cooperation under the Eastern Partnership. It should also keep the door open for additional DCFTAs. In this same spirit, the United States should consider free-trade agreements with Georgia, Ukraine, and other nations in the area, as the situation develops.

Equally important, the EU should make sure that it does not short its own interests and dilute its policies to suit Kremlin preferences, particularly in ways that strengthen Moscow’s hand over its neighbors. This is particularly important in the energy area. The EU Energy Charter, which Moscow has signed but not ratified, requires Europe’s energy partners to allow the use of their pipelines to deliver hydrocarbons to Europe.47Associated Press, “Greece, Macedonia Say New Name of Balkan Country is ‘Republic of Northern Macedonia,’” But, the EU does not insist that Gazprom open its pipelines to producers in Central Asia. This oversight strengthens Moscow’s hand as an energy supplier to Europe, and gives it additional leverage over countries that, it claims, fall into its natural sphere of influence.

Just as damaging is the EU’s countenancing the construction of the Nord Stream II pipeline from Russia to Germany. As an economic project, Nord Stream II makes sense for no nation. (A May 2018 Sberbank report makes the point that the project is only of value to vested interests in Russia that will work on the project.)48Alex Fak and Anna Kotelnikova, “Russian Oil and Gas: Tickling Giants,” Sberbank CIB, May, 2018, http://globalstocks.ru/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Sberbank-CIB-OG_Tickling-Giants.pdf. But, Nord Stream II makes geopolitical sense for Russia, because it reduces the country’s need for the current pipelines that run through Ukraine and Belarus. It is not in Europe’s geopolitical or energy interests to help increase Russian energy leverage. The European Commission has the power to stop this project.49Tobias Buck, “Nord Stream 2: Gas Pipeline from Russia That’s Dividing Europe,” Irish Times, July 21, 2018, https://www.irishtimes.com/news/world/europe/nord-stream-2-gas-pipeline-from-russia-that-s-dividing-europe-1.3571552. If German Chancellor Angela Merkel will not, or cannot, turn off Nord Stream II, the commission should do so.

NATO and the EU should also maintain and enhance policies designed to help the countries of the borderlands strengthen domestic vulnerabilities that the Kremlin has exploited to promote its influence. This must include programs designed to limit corruption, and to clean up the banking sector. Moscow continues to buy influence through corruption, and the banking system is a prime facilitator—as well as a means for money laundering.50Anders Aslund, How the United States Can Combat Russia’s Kleptocracy (Washington, DC: Atlantic Council, 2018), http://www.atlanticcouncil.org/publications/issue-briefs/how-the-united-states-can-combat-russia-s-kleptocracy. While Georgia has taken great strides to clean up its banking sector and reduce corruption, much more needs to be done in Ukraine and Moldova. The West’s support reforms through the use of conditional aid is an essential tool.

The security organs are another vulnerability. After the Soviet Union fell apart, Russia’s FSB and GRU made sure to retain and place agents in their counterpart ministries in neighboring countries. In the Donbas, when a large number of police and secret police joined the Russian hybrid war against Ukraine in spring 2014, Kyiv learned how dangerous this can be.

Ukraine has done a great deal since those dark days of 2014 to clean up its security agencies. But, more can be done, there and in Moldova. The United States or other NATO partners, such as the UK or Poland, should offer a program to vet Ukraine’s officials in the Ministries of Defense and Interior and in its security services. This will be easier to do if there are parallel efforts to root out corruption.

Security assistance in the short and medium terms

Russia is currently occupying and militarizing Ukrainian Crimea, conducting a simmering, hybrid war in the Donbas, and obstructing Ukrainian shipping in the Sea of Azov.51RFE/RL, “U.S. Condemns Russian ‘Harassment’ Of Shipping In Sea Of Azov,” RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty, August 31, 2018, https://www.rferl.org/a/u-s-calls-on-russia-cease-harassment-international-shipping-sea-azov-/29462170.html. Moscow launched a war against Georgia in 2008, and its “peacekeepers” in South Ossetia periodically move the line of demarcation farther into Georgia. The United States and NATO have provided both Ukraine and Georgia with training and military equipment.52Josh Lederman, “Officials: U.S. Agrees to Provide Lethal Weapons to Ukraine,” USA Today, December 23, 2017 https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2017/12/22/lethal-weapons-ukraine/978538001/. Under the Donald Trump administration, the United States, at long last, has provided lethal weapons—Javelin missiles—to both countries.

The United States and its allies should consider further weapons transfers to Georgia, and especially to Ukraine. Stopping Kremlin revisionism is a vital Alliance interest. The front in this struggle is currently in Eastern Ukraine. This justifies an annual Western aid package of $1 billion for five years for military equipment.53Sabrina Siddiqui, “House Approves $1 Billion Aid Package For Ukraine,” Huffington Post, March 07, 2014 https://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/03/06/house-ukraine-aid_n_4913495.html. mIt should include regular needs, such as anti-tank missiles, secure command-and-control communications, sophisticated drones, and anti-aircraft radar for missiles. It should also include anti-aircraft equipment and anti-ship missiles, to dissuade Moscow from using air power or launching amphibious operations against Ukraine.

Under the same logic, the United States should consult with Georgia on its military needs. The United States, with its NATO allies, should also consider a greater presence in the Black Sea region. Regular exercises with Georgia and Ukraine should be enhanced, as should port visits to Batumi and Odesa. Romania is a natural partner with which to develop a more robust program, and the United States should consider ways to draw Turkey and Bulgaria into greater cooperation.

It would also be useful for the United States and the EU to consider a proactive use of sanctions to deter further Kremlin aggression. To date, sanctions have been used to punish the Kremlin for past sins, but they also can be used to discourage further aggression.54Patricia Zengerle, “U.S. Senators Introduce Russia Sanctions ‘bill from Hell’,” Reuters, August 03, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-russia-sanctions/us-senators-introduce-russia-sanctions-bill-from-hell-idUSKBN1KN22Q. They can, and should, be applied in specific instances: when despite a “ceasefire,” the Kremlin keeps taking more territory in the Donbas, and when it moves the line of demarcation another fifty meters into the rest of Georgia. The United States and the EU should also look closely at Kremlin provocations in the Sea of Azov, and consider an appropriate response. Perhaps it should not permit Russian ships sailing from ports in the Sea of Azov to call at European and US ports, so long as Moscow is obstructing Ukrainian shipping there.

Photo Credit:(https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/20/A_Ukrainian_cadet_scans_the_area_for_simulated_opposing_forces_during_

exercise_Rapid_Trident_2014_in_Yavoriv%2C_Ukraine%2C_Sept_140923-A-DO651-001.jpg)

Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Belarus

This paper has focused principally on Georgia and Ukraine, and, to a lesser degree, Moldova. But, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Belarus are also part of the grey zone. They receive less attention because they have not pursued closer relations with the EU (or NATO) as energetically as Georgia and Ukraine, and, therefore, have received less pressure from the Kremlin. Still, they have been subject to pressure.

Moscow’s stance on the disputed region of Nagorno-Karabakh is designed partly to provide a lever on Baku, which—from Moscow’s point of view—cooperates too closely with the West on energy issues. Russian economic pressure persuaded Yerevan to walk away from a DCFTA with Brussels.55Laurence Peter, “Armenia Rift over Trade Deal Fuels EU-Russia Tension,” BBC News, September 05, 2013, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-23975951. And, Moscow has put serious pressure (including a gas cutoff) on close ally Belarus, and is now looking for a permanent military base there.56Alastair Macdonald, “Eyeing Possible Polish U.S. Base, Belarus Says No Russian Base, For…,” Reuters, May 31, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-belarus-eu/eyeing-possible-polish-us-base-belarus-says-no-russian-base-for-now-idUSKCN1IW339.

The United States and the EU should look for ways to increase cooperation with Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Belarus. The West cannot ignore the human-rights situation in Azerbaijan (nor, indeed, abuses in Armenia and Belarus), but that should be one item on the agenda. It should not be forgotten that, if Baku moves closer to Moscow, the prospects for human-rights improvements in Azerbaijan drop sharply.

The West should also take advantage of the recent political opening in Yerevan. The EU should not push, but it should let new President Armen Sarkissian know that the DCFTA Yerevan rejected two years ago is still on the table. Washington should also let Yerevan know that the door is open to better relations.

The West’s policy of minimal contact with the government of Belarus has yielded little fruit. Washington and the EU should offer Minsk talks on relations with the West, and regarding the situation in the region. President Alexander Lukashenko would welcome that as at least a small card to play as he tries to fend off Kremlin plans to establish a military base in his country.

The expansion of NATO and the EU since the mid-1990s launched an unparalleled period of stability and prosperity in Europe and beyond. This process stalled once Moscow began to push back hard in Georgia and then Ukraine, and as the EU was hit with the immigration crisis and Brexit. Now that the West has taken the measure of Moscow’s policy—and recognizes its revisionist aims—it should be clear that accepting Kremlin prerogatives in the borderlands is no recipe for peace.

A determined West has the power to make it easier for the countries of this region to choose their own future. Both its principles and its interests make this the right decision.