Ukraine conducted its presidential election in accordance with democratic standards, reflected in the assessments of credible international observers. It did so despite clear Russian interference in Ukraine’s election, though the interference was not extensive enough to affect the election’s outcome or the actual voting process.

While the interference did not live up to worst fears, numerous examples of it can be found in the kinetic, disinformation, and cyber realms over a period of months. Russia’s war with Ukraine and its occupation of parts of Ukraine’s territory constitute the most blatant interference, including the disenfranchisement of some 16 percent of the electorate living in Crimea and areas around Donetsk and Luhansk.

Russian interference in the election is part of President Vladimir Putin’s regime’s larger efforts to impede Ukraine’s sovereign right and determination to remain independent and choose its own future and foreign policy orientation. Russian disinformation and propaganda sought to discredit the election as illegitimate and rigged, and frame Ukraine as a failed state run by fascists and neo-Nazi sympathizers. Kremlin-backed rhetoric argued that Ukraine could not possibly conduct democratic elections—and Ukrainians disproved this line completely.

Heightened vigilance by Ukrainian authorities and civil society helped to reduce its potential impact. In contrast to 2014, when Russian cyberattacks compromised the Central Election Commission network, Ukrainian authorities were more prepared for possible attacks in 2019. As a result, during the first and second rounds of the presidential election—despite numerous minor cyber incidents—Ukraine did not suffer a major cyberattack.

The West must help Ukraine defend itself against Russian kinetic, cyber, and disinformation threats, especially with parliamentary elections coming this fall. Ukraine is a frontline state and testing ground for Russia’s nefarious activities, and the West has an obligation to support Ukraine against such threats in its pursuit of a democratic, Euro-Atlantic future.

Introduction

Western democracies have been slow to recognize the grave threats posed by external meddling, but Ukraine has—for five years—been both a target and testing ground for Russian “hybrid” attacks and other external interference. If its allies fail to properly record and analyze the tactics used against Ukraine, nothing will prevent Russia or other foreign entities from replicating these attacks elsewhere.

The ongoing military conflict on Ukrainian soil continues to significantly shape the country’s political agenda. During the election period, a proposed “peace recipe” to end the conflict in eastern Ukraine distracted voters from other pressing issues, such as economic development, cyber defense, and general infrastructural advancements. With ongoing hostilities at the forefront of national discourse, electoral platforms and candidate personalities matter less when voters consider their favored candidate for the presidency. Since most of the electorate hardly realized the complexity of the conflict’s roots and dynamics, populists’ simple solutions appealed to many supporters who rightfully desire peace. This desire provided the Kremlin with the opportunity to use the conflict it created to influence both the candidates’ agendas and the voters’ priorities.

Recognizing the high stakes, the Atlantic Council, the Victor Pinchuk Foundation, and the Transatlantic Commission on Election Integrity established the Ukrainian Election Task Force. Working with other Ukrainian institutions—StopFake and the Razumkov Centre—the three partners created a rapid-response team with the ability to monitor, evaluate, and disclose the full range of foreign subversive activities in Ukraine, and to propose suitable responses.

On a daily basis, the task force—under the leadership of David J. Kramer, former US assistant secretary of state—monitored and analyzed different sources of information available in Russian, Ukrainian, and English (including print media, the Internet, and television). These sources included selected event reports, official statements, articles, etc., which the task force analyzed and categorized by their direct or indirect relation to its mission. The Razumkov Centre, with Oleksiy Melnyk in the lead, monitored kinetic activities. For the purposes of this project, the “kinetic” category included normally understood military activities, as well as actions taken by the special services and paramilitary structures, and other acts of violence supposedly committed or inspired by a foreign power. Periodically, the kinetic lead conducted consultations with other experts in domestic policy and elections to validate the task force’s conclusions and assumptions. The kinetic lead also met with high-level officials of the National Security and Defense Counsel and the Security Service of Ukraine, who kindly shared their opinions and nonrestricted information (even if not publicly available), helped to check facts obtained from media, and provided useful suggestions for the task force’s work.

Following the project’s inception, the task force recorded and categorized a number of cases as interference efforts. The November 26, 2018, Kerch Strait incident, involving a Russian naval attack on three Ukrainian vessels with the wounding of several Ukrainian sailors and the capture of twenty-four Ukrainian service members, that forced a response from Ukraine’s government, emerged as one of the most significant examples of Russian interference. The incident raised concerns in some circles that the presidential election would be postponed as a result; instead a limited martial law was declared for only thirty days and the election remained on schedule. In addition to the information already published, the kinetic team maintained a collection of files that tracked suspicious cases to be watched closely, identifying potential areas and tools of external interference.

Alexei Venediktov, editor in chief of Eho Moskvy—a quasi-independent, Gazprom-owned outlet—announced the “name” of the most desirable winner of Ukraine’s elections for Russia. Pretending to read Putin’s mind, he said, “If we are talking about our Russian candidate in Ukraine…Mister Chaos is our candidate. The more chaos, the weaker a candidate—is more beneficial for Russia.” In Venediktov’s opinion, names and pro-Russianness are not important for Putin, because chaos will come, in fact, not in March-April, but in September-October. “Mr. Chaos will satisfy us.”1“Alexey Venediktov: vybory na ‘Ehe,’ Felgengauer i vstrecha s Putinym,” RTVI, March 20, 2019, https://rtvi.com/na-troikh/aleksey-venediktov/.

It would have been wrong to differentiate Russian cyber, disinformation, and kinetic actions aimed at election interference from the much broader context of the two countries’ bilateral relations—especially the Russian hybrid war against Ukraine. Russian interference is a long-term endeavor. It does not start with a beginning of an electoral campaign, and will not end after elections, if ever, assuming that Vladimir Putin stays in power.

Russia had at least two major incentives for meddling in Ukraine’s elections, and for its aggressive policy toward Ukraine in general. First, Ukraine’s success in becoming a prosperous, functional, and liberal democracy and European country is an existential threat to the current Russian autocracy.2“Elmar Brock: Ukraine’s Success—Worst Thing that Could Happen to Russia,” Interfax-Ukraine, December 23, 2016, https://interfax.com.ua/news/interview/392660.html. Second, Ukraine as a sovereign and independent state, and a potential member of the Euro-Atlantic community, undermines Putin’s imperial and geopolitical ambitions.3Peter Dickinson, The Geopolitical Divorce of the Century: Why Putin Cannot Afford to Let Ukraine Go, Atlantic Council, September 18, 2018, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/the-geopolitical-divorce-of-the-century-why-putin-cannot-afford-to-let-ukraine-go. This is why Russia has used, and will continue to use, all its capacities—including military power—to achieve its objectives concerning Ukraine.

The cyber team worked under Laura Galante, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council, and included two Ukrainian experts. When analyzing cyber operations ahead of the 2019 election, it was safe to assume that Ukraine would be a testing ground for cyberattacks that Russia would refine and later deploy against the West. In some ways, this has already been the case: Russian military hackers defaced and exploited the network of the Central Election Commission in 2014, an attack widely seen as a precursor to Kremlin’s later meddling in the 2016 US election.

However, a deeper look sheds some doubt on the “testing ground” theory. The malicious cyber operations conducted against Ukraine since 2014 remain unique to Ukraine, in both substance and scope. Whether it was NotPetya in 2017—the costliest cyberattack recorded—or the Black Energy cyberattacks on the power grid in 2015 and 2016, there is not yet evidence that these attacks have been replicated elsewhere, including in the West.

A more complete analysis must view cyber operations taking place in Ukraine as part of the larger war to undermine Ukraine’s sovereignty, the domestic public’s perception of the government’s competence, and Ukraine’s reputation in Europe and beyond. The tools and targets used to conduct cyber operations in Ukraine certainly provide a window into a malicious actor’s capabilities, and observers would be wise to weigh heavily the intent and context of these operations. It is with this multifaceted lens that the task force’s cyber element analyzed developments during the 2019 elections.

The disinformation team was led by Jakub Kalensky, Atlantic Council senior fellow and former disinformation lead at the European Union’s East StratCom Task Force, and consisted of several experienced Ukrainian civil society organizations and analysts. Dedicated television monitoring identified key disinformation narratives planted by the Kremlin on the most important Russian television shows. Partner Detector Media performed this task on a weekly basis. This monitoring then facilitated the tracing of Russian-originated disinformation messages online—both in Russia, and in the pro-Kremlin sources in Ukraine. Partner StopFake.org and task force analyst Roman Shutov traced these messages and provided regular updates and reporting, as well as necessary context and analysis.

General Philip M. Breedlove once described the Kremlin’s information aggression as “the most amazing information warfare blitzkrieg ever seen in the history of information warfare.”4John Vandiver, “SACEUR: Allies Must Prepare for Russia ‘Hybrid War,’” Stars and Stripes, September 4, 2014, https://www.stripes.com/news/saceur-allies-must-prepare-for-russia-hybrid-war-1.301464. A few days later, Peter Pomerantsev called Breedlove’s evaluation “something of an underestimation.”5Peter Pomerantsev, “Russia and the Menace of Unreality,” Atlantic, September 9, 2014, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2014/09/russia-putin-revolutionizing-information-warfare/379880/. Since then, the Kremlin has only expanded its capabilities, as have other foreign powers. The disinformation ecosystem supported and fed by Russia’s state media, within and beyond its borders, has grown in the past five years, and has been aided by the creation of new disinformation channels, proxies, fellow travelers, and useful idiots spreading the Kremlin’s lies.6“The Strategy and Tactics of the Pro-Kremlin Disinformation Campaign,” EU vs Disinfo, June 27, 2018, https://euvsdisinfo.eu/the-strategy-and-tactics-of-the-pro-kremlin-disinformation-campaign/. These channels repeat the Kremlin’s disinformation narratives incessantly, the audience’s familiarity with these narratives grows in tandem, and gradually, disinformation becomes fact.

Since 2014, Ukraine has been the primary target of the Kremlin’s information aggression.7“Ukraine Under Information Fire,” EU vs Disinfo, January 7, 2019, https://euvsdisinfo.eu/ukraine-under-information-fire/. The disinformation machine consistently tried to denigrate and dehumanize Ukrainians. The Kremlin aimed to discredit Ukraine’s democratic institutions, its post-Maidan political reorientation and with it the departure of Viktor Yanukovych from power and new elections, its pivot toward the West, and its commitment to democracy and the rule of law.

Many of these information weapons helped the Kremlin in its attempts to weaken the Ukrainian state. This long-term messaging also facilitated short-term, tactical information operations designed to discredit a particular candidate or interfere in a particular election.8“The Pro-Kremlin Disinformation Campaign.” EU vs Disinfo.

Below, the cyber, disinformation, and kinetic teams outline their findings concerning Kremlin interference in Ukraine’s presidential election.

Kinetic activities

The March 2019 presidential election was a serious test for Ukraine’s democracy. The Ukrainian people and Ukraine’s partners had high expectations for both the quality and outcomes of the elections. Ukrainians might be divided on plenty of issues that are at stake in this election, but they are predominantly united in their desire for peace, freedom, and prosperity. Ukrainians have already paid an extraordinary price for their choice to live in a free, prosperous, democratic, and European country. Indeed, Ukraine has many internal problems that hinder the country’s development, and the enduring Russian hybrid aggression complicates the task considerably.

Not unexpectedly, Russia has continued to impede Ukraine’s sovereign right and determination to become independent and distance itself from its neighbor. The Kremlin understands well that Ukraine’s 2019 presidential and parliamentary elections have the potential to boost or hinder the nation’s advance toward liberal democracy.

President Vladimir Putin constantly expressed his dissatisfaction with the current government of “Russophobes” in Kyiv, and his hopes for the new government to be more cooperative.9Vladimir Putin, annual news conference, December 20, 2018, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/59455. Because the chances of a pro-Russian candidate winning the presidential election in 2019 had appeared to be next to nil, Russian actions were aimed at creating as much chaos as possible by supporting or facilitating instability, insecurity, and uncertainty before, during, and after the election.

Likewise, looking at kinetic instruments of Russian interference, it would have been inappropriate to consider only subversive military or special-services activities. According to Army General Valery Gerasimov, chief of the Russian General Staff, “military force gets involved when non-military methods (economic, diplomatic, information, demonstration of force to underpin non-military measures) have failed to achieve indicated [war] objectives.”10“Vektory razvitiya voennoj strategii,” Krasnaya Zvezda, March 4, 2019, http://redstar.ru/vektory-razvitiya-voennoj-strategii/?attempt=2. Gerasimov’s interpretation of “Pentagon’s new strategy” should be acknowledged as a true presentation of the Russian “Trojan horse,” which carries gangs, private military companies, quasi-states, and fifth columns, as well as many other successfully weaponized nonmilitary items in the Russian hybrid-war inventory (cyber, disinformation, religion, language, history, culture, law, etc.).

At the end of the presidential election process, one can conclude that Gerasimov’s perception of modern warfare and the new ideas of the Russian Military Doctrine (internal destabilization with simultaneous high-precision strikes, preventive measures as an “active defense strategy,” humanitarian operations, or “limited actions strategy,” etc.) was tested in the context of Ukrainian elections, though not as massively as some had feared.

The kinetic team recorded a number of Russian actions aimed at disturbing the electoral process. Unlike cyber or disinformation, there was no apparent increase in the kinetic category during the two months of the presidential campaign.

In March, the Security Service of Ukraine reported a successful operation preventing a terrorist attack in the city of Kharkiv, which was aimed at destabilizing the political situation on the eve of the March 31 election. According to the SSU report, Russia’s Federal Security Service (FSB) recruited a local man to set off an explosion in one of the city’s underground train stations.11“Kharkiv: SBU Prevents Terrorist Act in Subway,” Security Service of Ukraine, March 22, 2019, https://ssu.gov.ua/ua/news/1/category/2/view/5885#.DcaQ3LTI.dpbs.

A number of provocative attacks on churches belonging to the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, Moscow Patriarchate, took place in southern regions of Ukraine in the weeks leading up to the election. These subversive activities seemed to be planned and coordinated from one center, as most of the attacks were conducted in a very similar way: arson and the drawing of Nazi or other extreme right-wing symbols on walls. Reportedly, “these actions were ordered, set up and financed by Russian special services” and “aimed to destabilize the social and political situation in our country via the use of artificial religious conflicts.”12“Vasyl Hrytsak: Attacks on UOC Religious Buildings Organised from Occupied Donbas Territories, Coordinated by FSB (Video),” Security Service of Ukraine, February 18, 2019, https://ssu.gov.ua/en/news/1/category/2/view/5739#.URw0M6cx.dpbshttps://ssu.gov.ua/en/news/1/category/2/view/5739#.URw0M6cx.dpbs%E2%80%9DRussian%20special%20services.

A possibility of large-scale Russian aggression had been the big question hanging over the election.13Oleksiy Melnyk, “Is Russia-Ukraine Large-Scale War (Im)possible?” Ukrainian Election Task Force, February 11, 2019, https://ukraineelects.org/kinetic/is-russia-ukraine-large-scale-war-impossible/. On the one hand, there were plenty of facts indicating Russia’s military, political, and psychological readiness for an offensive operation. On the other hand, there was a predominant view—mostly outside Russia—that the risk of a large-scale, open military aggression enormously outweighed any possible benefits for the Kremlin.

Those who believe that all the discussions about a Russian military buildup along the border are mostly provocations, to mobilize Western support and play a psychological game with Ukrainian voters, are not necessarily spreaders of Kremlin deceptions. Their judgement might be shaped solely by a normal logic regarding pros and cons for Russia and possible consequences for Russia’s national interests, international image, and economy. However, there are two important factors to keep in mind when trying to gauge the likelihood of a large-scale war scenario. First, Vladimir Putin holds almost unrestricted power to alone determine what constitutes his interest. Second, the Kremlin and President Putin have expressed desire and willingness to protect their understanding of Russian interests, Russians, Russian speakers, and the Russian Orthodox Church.14“Amid Church Rift, Kremlin Vows to ‘Protect Interests’ of Faithful in Ukraine,” RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty, October 12, 2018, https://www.rferl.org/a/amid-church-rift-kremlin-vows-to-protect-interests-of-faithful-in-ukraine/29540533.html.

The ongoing military conflict on Ukrainian soil continues to significantly shape the country’s political agenda.

Russia’s aggressive policy has been successfully conceptualized, institutionalized, and tested. The Russian strategy of “active measures”—which includes the organization and support of quasi-states with limited recognition and the use of “limited” military actions against neighbors and further abroad—has proven economical and effective. The lack of international reaction to Russia’s open attack on Ukrainian ships in the Kerch Strait in November 2018 strengthened Putin’s sense of impunity. Russian military maneuvers on the eve of Ukraine’s presidential elections appeared to send a very clear message of “We can repeat!” to Ukraine and to the West.15On March 23–26, fifteen hundred paratroopers with three hundred pieces of military equipment practiced an assault landing from the air and sea in Russia-occupied Crimea. Their mission was to capture and hold positions on a fortified coastline, with the aim to support landing of the main force operation backed by artillery, airpower, and battle tanks. “More than 1,500 Paratroopers Take Part in Massive Drills in Crimea,” TASS, March 25, 2019, http://tass.com/defense/1050339. On March 27, 2019, Russian Border Guard, Air Force, and Navy conducted joint exercise aimed at denial of foreign military ships’ passage through the Kerch Strait. “V Krymu yna ucheniyah predotvratili popytky korabley-narushiteley proyti cherez Kerchenskiy proliv,” TASS, March 28, 2019, https://tass.ru/armiya-i-opk/6268880.

The Russo-Ukrainian conflict itself was the most effective kinetic tool to influence Ukraine’s electoral processes and overall political agenda. The illegal annexation of Crimea and de-facto occupation of a part of the Donbas region have deprived millions of Ukrainian citizens of their constitutional right to participate in national elections. Ukrainians who remain in Crimea or occupied Donbas territories, and those who have escaped to Russia from the war zone, had to travel twice to the government-controlled territories to cast their votes. The maximum capacity of all crossing points is up to twenty-five thousand people a day, which is about 1 percent of those concerned.16“Border Control Points: People’s Monthly Crossings,” State Border Guard Service of Ukraine, last updated March 2019, https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiYTdiM2VlOGEtYTdlZi00OWI4LTlhNTgtZGFhNWNkMGZiMmZjIiwidCI6IjdhNTE3MDMzLTE1ZGYtNDQ1MC04ZjMyLWE5ODJmZTBhYTEyNSIsImMiOjh9%20. This means that roughly one hundred days would have been needed for potential voters to cross the separation line, not including the number of hours waiting, the financial costs, and possible risks of intimidation. The occupying authorities issued strong warnings for those who would decide to take this risk.17“Okupanty ne puskatymut proukrainskyh zhyteliv Donbasu…,” UKRINFORM, March 21, 2019, www.ukrinform.ua/rubric-ato/2664316-okupanti-ne-puskatimut-proukrainskih-ziteliv-donbasu-na-vibori-rozvidka.html

Managing escalation or de-escalation of the conflict equally served a purpose. The escalation after the November 25, 2018 Kerch Strait incident forced Kyiv to declare martial law for thirty days. If extended, this could have led to a postponement of the March 31 presidential election. Despite well-versed expectations, the Kremlin finally decided not to proceed with such a scenario.18“Lavrov Announces Military Provocation Before the End of December,” Ukrainian Election Task Force, December 19, 2018, https://ukraineelects.org/kinetic/lavrov-announces-military-provocation-before-the-end-of-december/. The Kremlin’s decision not to escalate the violence was likely due to its desire to weaken anti-Russian sentiment among Ukrainian voters, and to deprive Petro Poroshenko of war mobilization as an issue in his campaign.

The ongoing conflict on Ukrainian soil significantly undermined the level of internal stability, and made the task of destabilization much easier for Russia. The four-hundred-mile front line has not only been tremendously hard to defend, but has also been difficult to protect from smuggling of weapons and explosives. Ukrainian special services and police have discovered storages of weapons and explosives in quantities going far beyond conventional crime purposes.19Security Service of Ukraine, accessed March 26, 2019, https://ssu.gov.ua/en/search?search_request=TNT&news=1%20%20https://ssu.gov.ua/en/news/1/category/1/view/5821#.b0IMo8ld.dpbs.

The issue of prisoners of war (POWs) and political prisoners remains high on Ukraine’s political agenda.20“34 Ukrainians, 35 Political Prisoners, 24 POW Sailors Illegally Kept in Crimea and Russia,” Interfax-Ukraine, February 27, 2019, https://www.kyivpost.com/ukraine-politics/34-ukrainians-35-political-prisoners-24-pow-sailors-illegally-kept-in-crimea-and-russia.html. Dozens of Ukrainian citizens, including thirty-five political prisoners and twenty-four POW sailors, are being illegally kept in Crimea and Russia, as are more than one hundred hostages in Russian-controlled regions of Donbas. The Kremlin has used Ukrainian detainees for purposes of disinformation, subversion, and political blackmailing. It has also strategically awarded certain figures the power to free these people.

Of course, Russian actions are correlated with electoral cycles in a targeted country, and the interference presumably becomes more active and evident closer to the date of elections. However, it would be shortsighted to attribute all of these actions solely to the current electoral period. Being focused on the presidential campaign, the task force has already observed Russian actions aimed at the October 2019 parliamentary election, through clear support of pro-Russian political forces.21“Vstrecha Dmitriya Medvedeva s kandidatom v presidenty Ukrainy…,” Russian Government, March 22, 2019, http://government.ru/news/36147/. Moreover, it is highly likely that the main battle will take place during parliamentary elections.

Defending Ukraine in its struggle against Russian authoritarianism and imperial ambitions has been a task of global and historical importance. Ukraine’s elections are a great success for democracy. Judged as free and fair, they showed Ukraine’s continuous commitment and determination to achieve democratic norms.

Disinformation efforts

Until the last days before the election, the overarching strategy of the Kremlin could be identified as discrediting the election process, undermining Ukrainian authorities, and questioning the post-Maidan environment. However, before neither round of the election did the task force observe a strong push for a specific candidate.

That is probably the biggest difference compared to past elections and referenda in which researchers found Russia’s heavy hand. In a number of cases—the 2016 Brexit referendum and US elections, or Austrian presidential elections and the Dutch and Italian referenda in that year; the German and French elections in 2017 and the referendum in Catalonia in the same year; the Czech presidential elections last year—the Kremlin’s disinformation machine tried to promote a specific outcome or a specific candidate, and discredit the undesirable outcome or candidate.

Ukraine’s elections are a great success for democracy.

This did not seem to be the case before either round of the Ukrainian presidential election in 2019. According to task force monitors and analyses,22Ukrainian Election Task Force website, Chapter Disinformation, accessed April 11, 2019, https://ukraineelects.org/disinformation/ the majority of disinformation messages targeted at the Ukrainian elections stemmed from the grand narrative claiming that the elections would be rigged, illegitimate, and should not be trusted no matter the result. If there was one candidate who seemed to be attacked more often than his competitors, it was probably the incumbent, President Petro Poroshenko.23Detektor Media, Russian News Monitor: March 18-24, 2019, Ukrainian Election Task Force, accessed April 11, 2019, https://ukraineelects.org/disinformation/russian-news-monitor-march-18-24-2019/.

As for the narrative about allegedly rigged elections, the Kremlin’s propaganda bullhorns have been building it up for several months.24ЦЕНТРАЛЬНОЇ ВИБОРЧОЇ КОМІСІЇ, “ПОЗАЧЕРГОВІ ВИБОРИ НАРОДНИХ ДЕПУТАТІВ УКРАЇНИ,” October 26, 2014, https://www.cvk.gov.ua/info/protokol_bmvo_ndu_26102014.pdf. “This campaign is imitative by nature. They just pretend to have fair elections. They need this to demonstrate a nice picture of legitimacy to Americans,” said the TV channel of the Ministry of Defense, TV Zvezda.25“Открытый эфир. Ток-шоу,” Tv Zvezda, August 24, 2018, https://tvzvezda.ru/schedule/programs/content/201808241352-z30e.htm/. The messaging that elections would be rigged was a constant theme on Russian TV talk shows.26Detektor Media, Russian News Monitor: January 14-20, 2019, Ukrainian Election Task Force, accessed April 11, 2019, https://ukraineelects.org/disinformation/russian-news-monitor-january-14-20-2019/.

Kremlin propaganda sought to use the election to discredit not only Ukraine’s democratic processes but also Ukraine as a state.

To amplify this disinformation messaging, the Kremlin’s quasi-media also manipulated reporting of international organizations that observed the campaign. First, they misrepresented the report of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE)27“ПАСЕ призывает к транспарентности финансирования избирательной кампании на Украине,” TASS, accessed April 11, 2019, https://tass.ru/mezhdunarodnaya-panorama/6199445.; a few weeks later, the report of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE)’s Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) was manipulated.28“БДИПЧ ОБСЕ отмечает большое число сообщений о подкупе голосов перед выборами на Украине,” TASS, accessed April 11, 2019, https://tass.ru/mezhdunarodnaya-panorama/6222574. In both cases, the Moscow-controlled outlets ignored the generally neutral, or even positive, tone of the reports (PACE praised the country’s preparedness for the elections; ODIHR found that the election was in line with constitutional provisions), and hyperbolized even the smallest negative elements.

Similarly, Kremlin propaganda sought to use the election to discredit not only Ukraine’s democratic processes but also Ukraine as a state. Kremlin outlets voiced many false accusations about the alleged spread of Nazism in Ukraine,29Detektor Media, Russian News Monitor: February 25 – March 3, 2019, Ukrainian Election Task Force, accessed April 11, 2019, https://ukraineelects.org/disinformation/russian-news-monitor-february-25-march-3-2019/. or about the Ukrainian state planning terror attacks and contract killings on its territory in order to influence the elections.30“МЕНЯ КИНУЛИ КАК ЛОХА: 15 ЧЕСТНЫХ ОТВЕТОВ ЯНУКОВИЧА НА 15 «ИСКРЕННИХ» ВОПРОСОВ ЖУРНАЛИСТОВ. ПОЛНЫЙ ТЕКСТ,” NewsOne, Accessed April 11, 2019, https://newsone.ua/news/politics/janukovich-daet-press-konferentsiju-v-moskve.html. In one of the more erratic attacks, the Ukrainian army was accused of cannibalism and occultism.31Detektor Media, Russian News Monitor: March 25-31, 2019, Ukrainian Election Task Force, accessed April 11, 2019, https://ukraineelects.org/disinformation/russian-news-monitor-march-25-31-2019/.

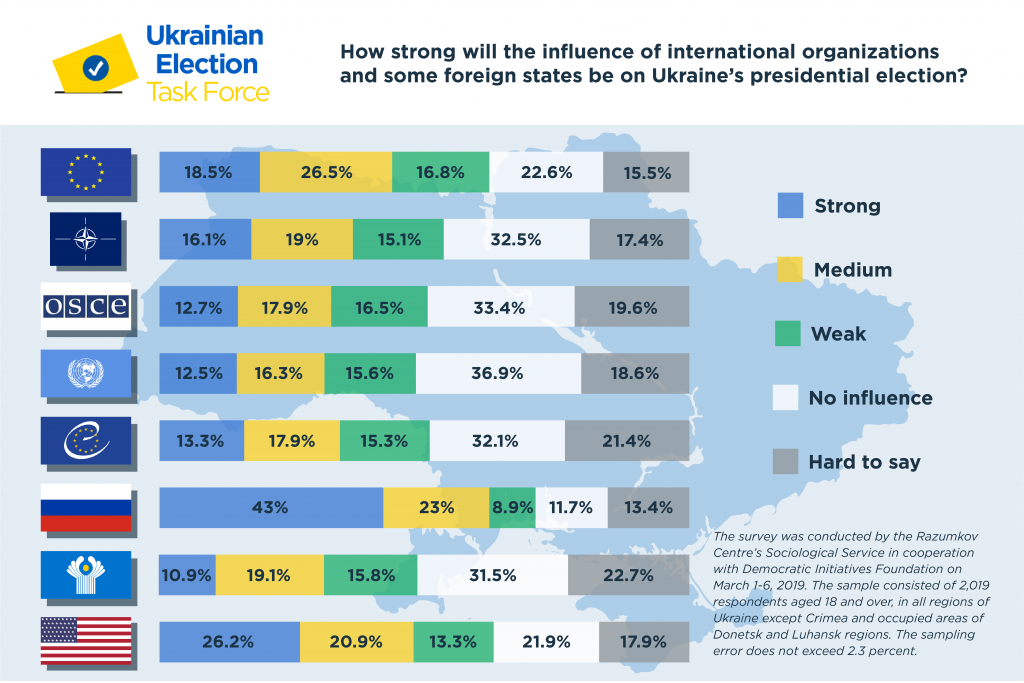

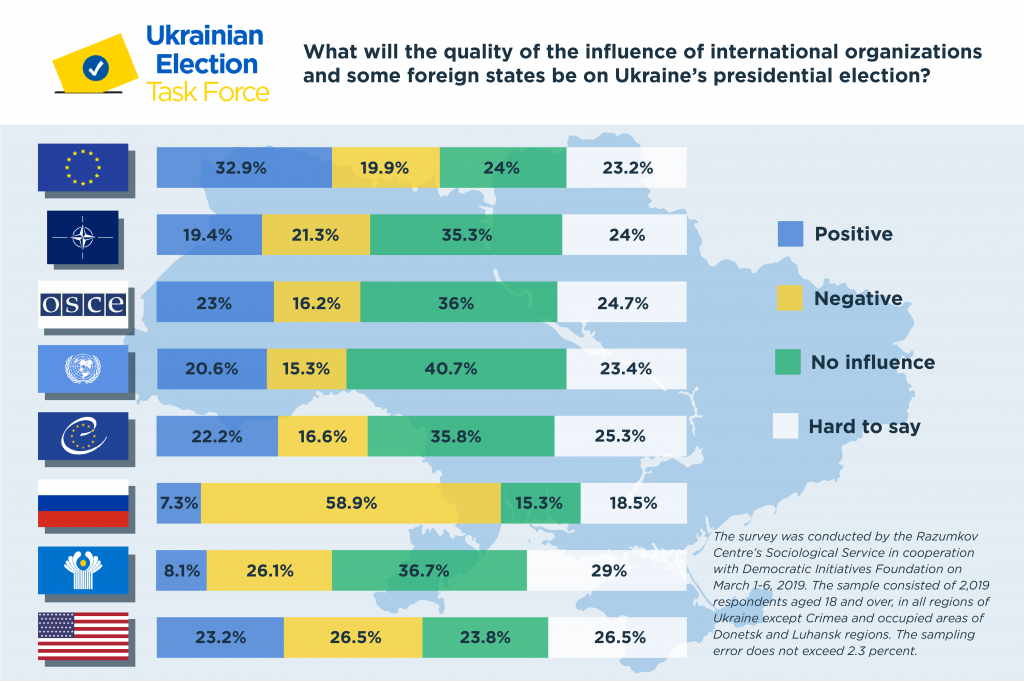

Another grand narrative spread during the election campaign depicted Ukraine as being under external control from the West.32Detektor Media, Russian News Monitor: February 18-24, 2019, Ukrainian Election Task Force, accessed April 11, 2019, https://ukraineelects.org/disinformation/russian-news-monitor-february-18-24-2019/. The desired effect is pretty much the same as in the narrative about the rigged elections. It does not matter what Ukrainian citizens themselves want—either the elections will be falsified, or they will be manipulated by the United States and Brussels, or both.

Despite the fact that none of the Kremlin-controlled disinformation has been proven right, Moscow once again resorted to the ancient tactic of “repeat a lie a hundred times and it will become the truth.” Thus, after several weeks of evidence-free accusations, the same invented accusations have been repeated by Russian Prime Minister Dmitri Medvedev.

“We in Russia do not yet see with whom we could talk in Ukraine…However, it matters whether the victory is fair, whether the election is legitimate and not rigged. Recent events make one suspect the worst. The presidential campaign in that country has featured flagrant violations of generally accepted democratic norms, including those guiding European countries,” Medvedev said.33“Dmitry Medvedev’s interview with Bulgarian newspaper Trud,” Government of the Russian Federation, Accessed on April 11, 2019, http://government.ru/en/news/35903/.

The Russian complaints had only two facts on which to be based: the closure of polling stations in Russia, and a ban on Russian election observers. These complaints were repeated throughout the campaign by various media and, finally, by Medvedev himself.34Ibid. To set the record straight: Ukraine could not guarantee the safety of voters in Russia,35“Klimkin comments on shutting down Ukrainian polling stations at diplomatic institutions across Russia,” UNIAN, accessed April 11, 2019, https://www.unian.info/politics/10398462-klimkin-comments-on-shutting-down-ukrainian-polling-stations-at-diplomatic-institutions-across-russia.html. so Ukrainians opened additional polling stations in neighboring countries in place of the closed polling stations. As for the ban on Russian citizens observing the elections, Ukrainian members of Parliament (MPs)36Interfax Ukraine, Rada bans Russians from monitoring elections in Ukraine, Kyiv Post, accessed April 11, 2019, https://www.kyivpost.com/ukraine-politics/rada-bans-russians-from-monitoring-elections-in-ukraine.html. decided that citizens of a country that leads war against Ukraine cannot observe Ukrainian elections. It is hard to deny the reasoning in both of these cases.

Within Ukraine, the Kremlin’s disinformation machine was echoed by the representatives of the self-proclaimed “People’s Republics” in Donbas, in the east of Ukraine. Leaders of the “republics” complained37“Заявление Главы ДНР Дениса Пушилина в связи с предстоящими выборами на Украине,” Denis Pushilin, February 21, 2019, https://denis-pushilin.ru/news/zayavlenie-glavy-dnr-denisa-pushilina-v-svyazi-s-predstoyashhimi-vyborami-na-ukraine/. that Ukraine leads an indiscriminate campaign against those who want to restore peace (which, in the lexicon of pro-Kremlin propaganda, means giving in to all of Moscow’s demands), accused the authorities of falsifications, and absurdly complained that the people who wage war against Ukraine are not allowed to participate in Ukrainian elections.

Unfortunately, some of the Kremlin-originated disinformation messages have successfully penetrated beyond their own information space. Thus, the task force heard an echo of the typically Russian false accusations about Ukraine as a semi-fascist state oppressing minorities—but, this time, from Budapest.38“Hungarian government official brands Ukrainian education law “semi-Fascist,” UNIAN, February 22, 2019, https://www.unian.info/politics/10456362-hungarian-government-official-brands-ukrainian-education-law-semi-fascist.html.

Although the task force didn’t have dedicated social media monitoring, members noticed that the New York Times reported on a new tactic that Russians used in the 2019 Ukrainian presidential election campaign.39Michael Schwirtz and Sheera Frenkel, In Ukraine, Russia Tests a New Facebook Tactic in Election Tampering, NY Times, accessed April 11, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/29/world/europe/ukraine-russia-election-tampering-propaganda.html?fbclid=IwAR2uGPPsFmeI1hQ-kyi0-x0oIEchO802QmKZHai2p-A9WnIfAdayQH4y4xQ. As the newspaper reported, instead of creating false accounts and misleading Facebook pages, Russians were trying to find genuine Ukrainians who would sell them their own Facebook accounts, and use these accounts to push political ads or plant fake stories.

It seems that Moscow propaganda aims to discredit the whole post-Maidan development of Ukraine. However, discrediting of democratic processes is something that has been seen before—be it the Brexit referendum, the German elections, or the US presidential election. The aim always remains the same: to undermine public faith in the democratic process, and to manipulate the audience into a feeling that, no matter what happens, the people will always be tricked and deceived.

Cyber operations

Ukraine has made great progress in cybersecurity since 2014, when hackers compromised Ukraine’s Central Election Commission (CEC) network in the “most technically advanced attack” ever investigated by the Ukrainian Computer Emergency Response Team (CERT-UA).40Nikolay Koval, “Revolution Hacking,” Chapter 6 in Kenneth Geers, ed., Cyber War in Perspective: Russian Aggression against Ukraine (Tallinn, Estonia: NATO CCD COE Publications, 2015), https://ccdcoe.org/uploads/2018/10/Ch06_CyberWarinPerspective_Koval.pdf. In 2019, during the first and second rounds of its presidential election—despite numerous minor cyber incidents, documented below—Ukraine did not suffer a major cyberattack.

Ukrainian political leadership set the tone for cyber defense early and often. The chief of Ukraine’s Foreign Intelligence Service, Yehor Bozhok, said Russia had allocated US$350 million to destabilize Ukraine and to meddle in its election.41“Ukraine’s Foreign Intel Service: Russia to spend US$350 mln for Meddling in Ukraine Elections,” UNIAN, January 25, 2019, https://www.unian.info/politics/10421127-ukraine-s-foreign-intel-service-russia-to-spend-us-350-mln-for-meddling-in-ukraine-elections.html. Serhiy Demedyuk, head of the cyber police, warned that well-known Russian hacker groups, such as Fancy Bear and the Shadow Brokers, were active in Ukraine, and were scaling up their activity prior to the election.42“Russian Hackers Scaled Up Activity in Ukraine Cyber Space Ahead of Election,” Institute Mass Information, March 18, 2019, https://imi.org.ua/en/news/russian-hackers-scaled-up-activity-in-ukraine-cyber-space-ahead-of-election/. The cybersecurity chief at the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU), Oleksandr Klymchuk, said Russia may opt to target national critical infrastructures like transport, communications, finance, or energy.43“Ukraine’s SBU to Block Websites Threatening National Security,” UNIAN, February 12, 2019, https://www.unian.info/politics/10443432-ukraine-s-sbu-to-block-websites-threatening-national-security.html.

Ukrainian political leadership set the tone for cyber defense early and often.

Despite these warnings, SBU Chief Vasyl Hrytsak said that Ukrainian law enforcement would do everything in its power to ensure election security, and CEC Chairperson Tetiana Slipachuk asserted that, “We are ready on a moral and technical level to respond to the challenges.”44“SBU Head Hrytsak Accuses Russia of Playing ‘Religious Card’ in Ukraine for Interference in Electoral Process,” Interfax-Ukraine, February 18, 2019, https://en.interfax.com.ua/news/general/566923.html; “Central Election Commission Ready to Respond to Russia’s Meddling in Elections,” UKRINFORM, March 31, 2019, https://www.ukrinform.net/rubric-elections/2670946-central-election-commission-ready-to-respond-to-russias-meddling-in-elections.html.

On a practical level, the Ukrainian government drafted a “Concept of Preparation for Repelling Military Aggression in Cyberspace,” with a view toward countering hybrid war, supporting defense-sector reform, and achieving interoperability with NATO.45“Oleksandr Turchynov: Russia is Going to Use the Entire Arsenal, Including Cybernetic Means, to Influence the Democratic Will of the Ukrainian People,” National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine, February 19, 2019, http://www.rnbo.gov.ua/en/news/3213.html. The Verkhovna Rada, Ukraine’s legislative body, voted for draft law No. 8496, which provided cyber defense funding for the Central Election Commission (CEC).46“VR Approves Bill on Strengthening Cybersecurity of Central Election Commission,” UKRINFORM, November 22, 2018, https://www.ukrinform.net/rubric-polytics/2585074-vr-approves-bill-on-strengthening-cybersecurity-of-central-election-commission.html. In June 2016, Ukraine created the National Center for Cyber Security to coordinate activities of all national agencies, including security for electoral servers.47“Ukraine Creates National Center for Cyber Security,” UNIAN, June 8, 2016, https://www.unian.info/society/1369157-ukraine-creates-national-center-for-cyber-security.html. The government also created a twenty-four-hour working group “to identify, prevent, and suppress any unauthorized actions with the CEC information resources.”48“Oleksandr Turchynov: Russia is Going to Use the Entire Arsenal, Including Cybernetic Means, to Influence the Democratic Will of the Ukrainian People,” National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine. Finally, the government created a national Malware Information Sharing Platform (MISP-UA) to offer real-time cyber-threat intelligence, in compliance with European Union (EU) and NATO standards, which is now used throughout the world.49“СБУ запустила платформу по противодействию кибератакам на выборах 2019 года РБК-Украина,” November 14, 2018, https://www.rbc.ua/rus/news/sbu-zapustila-platformu-protivodeystviyu-1542195394.html.

The private sector also tried to lend a hand. In January, Facebook announced a new initiative to promote transparency in political advertising, including indexing ads in a searchable online library. The ultimate goal was to make it difficult for foreign interests to run political advertisements in another country.50Paresh Dave, “Exclusive—Facebook Brings Stricter Ads Rules to Countries with Big 2019 Votes,” Reuters, January 15, 2019, https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-facebook-elections-exclusive/exclusive-facebook-brings-stricter-ads-rules-to-countries-with-big-2019-votes-idUKKCN1PA0C6. In March, Facebook explained that its ban on foreign political advertising in Ukraine’s election campaign included the illicit promotion of politicians, parties, slogans, and symbols, and that both automated and human analysis would be leveraged to safeguard the election’s integrity.51“Facebook Prohibits Foreign-Funded Ads for Ukraine Election—Media,” UNIAN, March 5, 2019, https://www.unian.info/politics/10468851-facebook-prohibits-foreign-funded-ads-for-ukraine-election-media.html.

US support for Ukraine’s cybersecurity had been tangible. In 2018, the State Department pledged $10 million in cybersecurity aid to Ukraine.52“Second U.S.-Ukraine Cybersecurity Dialogue,” US Department of State, press release, November 5, 2018, https://ua.usembassy.gov/second-u-s-ukraine-cybersecurity-dialogue/. In February 2019, Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko said the United States helped Ukraine stop a Russian distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attack against the CEC.53Sean Lyngaas, “Ukraine’s President Accuses Russia of Launching Cyberattack Against Election Commission,” Cyberscoop, February 26, 2019, https://www.cyberscoop.com/ukraines-president-accuses-russia-launching-cyberattack-election-commission/. During the 2018 US midterm election—an event that could have affected Ukraine in more ways than one—the US Army Cyber Command conducted a denial-of-service (DoS) cyberattack against the Russian Internet Research Agency (IRA).54Andy Greenberg, “US Hackers’ Strike on Russian Trolls Sends a Message—But What Kind?” Wired, February 27, 2019, https://www.wired.com/story/cyber-command-ira-strike-sends-signal/. In a recent speech, former US Director of National Intelligence (DNI) James Clapper said Moscow meddled in Ukraine’s 2014 elections and the United States’ 2016 elections using the same techniques, and had tested a range of attacks against Ukraine, including social-media manipulation and power-grid compromise.55“General James Clapper: Russia Uses Techniques Tested in Ukraine to Meddle in US Elections,” UKRINFORM, February 22, 2019, https://www.ukrinform.net/rubric-polytics/2645968-general-james-clapper-russia-uses-techniques-tested-in-ukraine-to-meddle-in-us-elections.html.

As the European Union prepares to secure its parliamentary elections in May, the EU and NATO have been studying cyberattacks in Ukraine. In March 2019, about one hundred Western experts took part in cybersecurity exercises with the SBU and Ukraine’s State Special Communication Service (SSCS).

The CEC received new training, hardware, and software, while foreign experts launched simulated cyberattacks against Ukraine, and local experts sought to neutralize them.56“Ukraine Ready to Take on Russian Election Hackers,” Agence France-Presse, March 18, 2019, https://www.securityweek.com/ukraine-ready-take-russian-election-hackers. Europol announced that the destructiveness of NotPetya (believed to be of Russian origin) and WannaCry (likely from North Korea) proved that existing cyber defenses are insufficient, and that more must be done to protect Europe.57“Law Enforcement Agencies Across the EU Prepare for Major Cross-Border Cyber-Attacks,” European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation, press release, March 18, 2019, https://www.europol.europa.eu/newsroom/news/law-enforcement-agencies-across-eu-prepare-for-major-cross-border-cyber-attacks. UK Defense Secretary Gavin Williamson said Russia aims to bring former Soviet states “back into its orbit,” in part with cyberattacks, and that Russia fights in a “gray zone” short of war. The cost of failing to address Russia’s aggression is “unacceptably high.”58“Resurgent Russia Aims to Bring Ukraine Back Into its Orbit—UK Defense Secretary,” UNIAN, February 11, 2019, https://www.unian.info/world/10442427-resurgent-russia-aims-to-bring-ukraine-back-into-its-orbit-uk-defense-secretary.html.

Looking ahead by looking back

Ukraine conducted its presidential election in accord with democratic standards reflected in the assessments of international observers, including the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe’s Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR), the International Republican Institute and the National Democratic Institute. Both the March 31 first round and the April 21 second round were free of violence. Turnout for both was roughly 63 percent, an impressive demonstration by Ukrainian voters that they will be the ones to choose their own leaders, not outside forces.

One of the best ways for Ukraine to defend itself against Russian interference is to stay on a democratic path.

That said, there is no denying Russian efforts to interfere in the Ukrainian election. The most obvious examples on the kinetic side of the ledger involve the fact that Russia is at war with Ukraine and Russia occupies parts of Ukraine’s territory. Conducting an election against the backdrop of war is not easy to do. Rampant rumors and reports of significant Russian military buildup and maneuvers along the Russian-Ukrainian border created a layer of nervousness ahead of the election. The Kremlin had no interest in batting down such reports since they contributed to Russia’s narrative of a Ukraine that is unstable and in chaos.

Russian occupation of Crimea and areas around Donetsk and Luhansk, as noted above, de facto disenfranchised nearly 16 percent of the Ukrainian electorate, approximately 4.8 million voters. At a minimum, it was extremely arduous for these voters to travel to safe polling stations to cast their ballots. In the search for instances of Russian interference, these examples stare in the face of observers.

When it comes to disinformation, since 2014 and Putin’s invasion of Crimea and incursion into the Donbas area, Russian propaganda has sought to portray Ukraine as a failed and illegitimate state run by fascists and neo-Nazi sympathizers. As the 2019 elections neared, the Kremlin-supported rhetoric maintained that Ukraine could not possibly conduct democratic elections. Kremlin propaganda outlets pumped out themes that the election was rigged and fraudulent, that the incumbent would resort to any means to ensure victory, and that Ukraine would launch violence against Russia to deflect attention from the election’s shortcomings.

None of this, of course, came to fruition. In an especially noteworthy refutation of Kremlin propaganda that Ukraine is run by fascists, Ukrainian voters, by a huge margin, opted for Volodymyr Zelenskiy, who is Jewish. They didn’t vote for him because he is Jewish, but the fact that he is had little to no bearing on their ballot choice, nor did it figure as an issue in the campaign, reflecting positively on Ukraine. In addition to Zelenskiy, current Prime Minister Volodymyr Groysman is also Jewish, making Ukraine the only country outside of Israel with Jewish leaders at the very top. It will be hard for the Kremlin to maintain the lie that Ukraine’s leaders are part of some extremist, right-wing, anti-Semitic conspiracy—though facts have never gotten in the way of Kremlin yarns before. Another common Kremlin theme that Ukraine is badly divided was also disabused, given that Zelenskiy garnered support in both rounds, but especially in the second, from all parts of the country.

Regarding cyber, there is no question that Ukrainian authorities were more prepared for possible attacks than they were in 2014. We must remember that the election in 2014 occurred several months after the Revolution of Dignity, and few were prepared for an election at that time, much less ready to defend against Russian cyber-attacks. Moreover, many state institutions had been infiltrated by Russian forces who facilitated Russian intrusions into Ukraine. In the most recent election, by contrast, Ukraine was acutely aware of the threats coming from Kremlin-supported operations. With help and support from the international community, Ukraine was better placed to defend against and deflect cyber interference than it was in 2014.

That worst-case fears were not realized in the 2019 election does not mean that authorities can let down their guard. This leads us to the first of our recommendations:

- Many observers expect Russian interference to be more active in the Rada elections in the fall, where single-mandate races and certain political parties more aligned with Kremlin thinking could give Russia openings to make inroads. Vigilance, which we saw from Ukrainian authorities in the presidential election, must be maintained for the parliamentary elections.

- Russia’s disinformation campaign against Ukraine will continue, and Ukrainian organizations and their international partners must maintain their efforts to expose and source such lies. Not every piece of disinformation can or should be traced, but where certain strains go viral, it is important to ensure that the truth prevails over the propaganda.

- Ukraine also needs to stay on heightened alert when it comes to both the military and security service threats. Even if there is no full-fledged Russian military incursion into Ukraine, the threat looms over the country and the Rada elections, and maintaining readiness to confront any challenge will reassure a sometimes jittery population.

- Ukraine and Ukrainian journalists must develop methods of explaining narratives that have been, or are likely to be, misinterpreted by the Kremlin and its disinformation distribution methods to audiences beyond Ukraine itself and the wider region. Ukrainian media, and relevant government bodies, should identify, highlight, and explain issues and events in Ukraine that are susceptible to distortion by Kremlin-aligned media outlets.

- Maintaining security for hundreds if not thousands of Rada candidates will be a challenging task, but Russian assassination attempts against certain politicians to sow unrest and fear cannot be ruled out. The safety of those participating in the electoral process—both candidates and voters—must be ensured.

- Cooperation on the cyber front between Ukrainian groups and their Western counterparts will remain essential. What happens in and to Ukraine when it comes to cyber is not likely to stay in Ukraine, suggesting a strong interest Western entities should have in helping Ukraine against this threat. This should include providing Ukraine with the latest defensive technologies and encouraging social media companies and Internet providers to police their networks for nefarious actors.

- As noted throughout this report, the West must help Ukraine defend itself against Russian kinetic, cyber, and disinformation threats. What Russia tries out in Ukraine could easily be tried elsewhere in Europe and the United States next. Ukraine is a frontline state and testing ground for Russian nefarious activities, and the West has an obligation to support Ukraine in its pursuit of a democratic, Euro-Atlantic future.

One of the best ways for Ukraine to defend itself against Russian interference is to stay on a democratic path. This is not easy to do, to be sure, with its larger neighbor breathing down its neck, launching attacks in the cyber realm, further threatening Ukraine militarily, and spreading lies and disinformation on a steady basis. Enabling Ukrainians to choose their leaders freely and through competitive elections is a key part of their democratic transition. It achieved this with the two rounds of the presidential election and can do the same with the upcoming Rada elections. Since 2014, the Russian threat has not receded, but Ukraine’s ability to confront it has improved significantly. That is vital for Ukraine’s success and interest in deeper integration into the Euro-Atlantic community and will redound to the benefit of the West and, eventually, one day, to Russia itself.