Hungary’s policy on China: Doing Beijing’s bidding

This is the seventh chapter of the report “Is Europe waking up to the China challenge? How geopolitics are reshaping EU and transatlantic strategy.” Read the full report here.

Among the varied China policies of European Union (EU) member states, Hungary’s position represents the extreme end of the spectrum. Under Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, the country has become China’s closest ally in the EU, effectively aligning its foreign policy with Beijing’s international priorities and repeatedly obstructing EU efforts to counter Chinese influence. In trade and investment, Hungary has welcomed sizeable Chinese investments, making it the largest recipient of Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in the EU in recent years. In technology, Budapest has embraced Huawei’s and ZTE’s participation in its telecommunications sector and partnered with China on numerous Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects, including several involving critical infrastructure. Since the start of Russia’s war on Ukraine, Hungary has even deepened its partnership with China on security matters—allowing Chinese police officers to work in the country and tolerating an expanding Chinese intelligence presence.

During the Cold War, Hungary’s relationship with China largely mirrored the trajectory of Soviet-Chinese relations. In the first decade after the establishment of the Hungarian People’s Republic and the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the Sino-Soviet partnership was close, and ties between Budapest and Beijing grew stronger in parallel. When the Sino-Soviet split emerged around 1959, Hungary’s relations with China likewise stagnated and then deteriorated through the 1960s and 1970s.

By the late 1970s, as Deng Xiaoping launched China’s “reform and opening up,” Beijing began to look to Hungary as a model for market-oriented reforms within a socialist framework. Chinese policymakers studied Hungary’s New Economic Mechanism—introduced in 1968 to decentralize economic decision-making—as well as its later reform experiments of the late 1970s and early 1980s. As Sino-Soviet tensions eased, Hungary and China gradually rebuilt and expanded their political and economic relations.

After Hungary broke free of the Soviet bloc in 1989, the focus of its foreign policy shifted toward Euro-Atlantic integration—particularly toward Western Europe and the United States—resulting in a period of neglect in relations with China, similar to that seen in other former Soviet bloc countries. Prime Minister Péter Medgyessy’s official visit to China in 2003 marked a renewed interest in developing Hungary-China relations in the 2000s, albeit within the limits of Hungary’s new membership in NATO and the EU.1Levente Horváth, “Magyar-Kínai Diplomáciai Kapcsolatok [Hungary-China Diplomatic Relations]” in Levente Horváth, ed., “Eredmények és Kihívások: A Magyar-Kínai Diplomácia 75 Éve [Achievements and Challenges: 75 years of Hungary-China diplomacy],” John von Neumann University, Eurasia Center, 2024, https://eurasiacenter.hu/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/75_evfordulo_online.pdf.

Since 2014, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán—while distancing his country from the EU mainstream and the United States and championing “illiberal democracy”—has gradually transformed Hungary’s foreign policy and grand strategy to align more closely with the interests of China and Russia.2Zoltán Fehér, “The Implications of the Rise of Small and Middle Powers for U.S.-China Great Power Competition” in Philip Baxter, ed., Examining Perspectives of Small-to-Medium Powers in Emergent Great Power Competition (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2025), https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-86901-3_10.

The Hungarian government portrays its ties with China and Russia as part of a “connectivity” and “economic neutrality” strategy, under which Hungary seeks to maintain open channels with all major powers and avoid participation in bloc formation.3Balázs Orbán, Hussar Cut: The Hungarian Strategy for Connectivity (Budapest: MCC Press, 2024). However, this is largely rhetorical, as the Orbán government has strained relations with most of its EU and NATO allies while actively cultivating close ties with the EU’s and NATO’s competitors and adversaries.4Zoltán Fehér, “Hogyan Csináljunk Nagystratégiát? [How to Do Grand Strategy?],” Országút, September 23, 2024, https://orszagut.com/kozelet/hogyan-csinaljunk-nagystrategiat-6792.

In reality, this represents a major strategic shift, as Hungary has intensified its engagement with Beijing and Moscow in economic, technological, and security affairs alike.5Fehér, “The Implications of the Rise of Small and Middle Powers for U.S.-China Great Power Competition.” Within the EU and NATO, the Hungarian government routinely advances Chinese and Russian interests in discussions on sensitive issues. In 2017, Hungary prevented the EU from joining a petition condemning China’s torture of detained attorneys.6Szabolcs Panyi, “Hungary in the Midst of a U.S.-Huawei War,” Direkt36, November 1, 2019, https://vsquare.org/hungary-in-the-midst-of-a-u-s-huawei-war/. In 2021, it blocked a statement criticizing China’s crackdown on democracy in Hong Kong7Hans von der Burchard and Jacopo Barigazzi, “Germany Slams Hungary for Blocking EU Criticism of China on Hong Kong,” Politico, May 10, 2021, https://www.politico.eu/article/german-foreign-minister-slams-hungary-for-blocking-hong-kong-conclusions/.—and in 2024, when NATO was considering labeling China as a “systemic challenge” to Europe, Hungary’s foreign minister protested, declaring that “Hungary does not want NATO to become an ‘anti-China’ bloc.”8“Hungary Will Not Support NATO Becoming ‘anti-China’ Bloc, Minister Says,” Reuters, July 11, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/hungary-will-not-support-nato-becoming-anti-china-bloc-minister-says-2024-07-11/.

Hungary has faced growing criticism within the EU and from the United States for its democratic backsliding, pervasive corruption, and increasingly anti-Western foreign policy. In December 2021, the European Commission suspended a significant portion of Hungary’s cohesion funds due to the Orbán government’s undermining of the rule of law and judicial independence, as well as concerns over corruption.9Zselyke Csáky, “Freezing EU Funds: An Effective Tool to Enforce the Rule of Law?” Centre for European Reform, February 27, 2025, https://www.cer.eu/insights/freezing-eu-funds-effective-tool-enforce-rule-law. In response to the loss of Western funding and investment, Hungary has turned to China and Russia for its public financing and economic development—attracting huge industrial investments from Chinese manufacturers, awarding critical infrastructure projects to Russian and Chinese companies, and accepting a $1 billion loan from China on secret, government-classified terms.

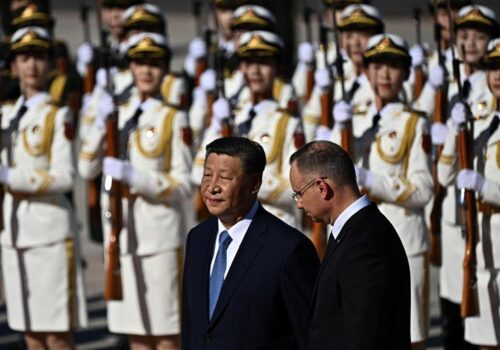

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to Hungary in May 2024 capped a decade of deepening Hungary-China relations.10Zoltán Fehér, “Xi Jinping Visited Europe to Divide It. What Happens Next Could Determine If He Succeeds,” Atlantic Council, June 1, 2024, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/xi-jinping-visited-europe-to-divide-it-what-happens-next-could-determine-if-he-succeeds/. After Orbán received Xi with much pomp and circumstance, the two leaders agreed to establish an “all-weather comprehensive strategic partnership”11James Kynge and Marton Dunai, “Xi Jinping Upgrades China’s Ties with Hungary to ‘All-Weather’ Partnership,” Financial Times, May 9, 2024, https://www.ft.com/content/563be6d0-ab62-47cc-9076-5dd20cac8cbd. and embark on what they called a “golden voyage” in bilateral relations.12Csin-ping Hszi, “Kína és Magyarország Együtt Lép az ‘Arany Vízi Útra,’” Magyar Nemzet, May 7, 2024, https://magyarnemzet.hu/velemeny/2024/05/kina-es-magyarorszag-egyutt-lep-az-arany-vizi-utra#google_vignette. They signed several cooperation agreements in areas spanning railway and border infrastructure, oil pipelines, electric vehicle (EV) charging networks, and nuclear energy projects.13Bela Szandelszky, “Hungary and China Sign Strategic Cooperation Agreement during Visit by Chinese President Xi,” Associated Press, May 9, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/chinas-xi-welcomed-hungary-talks-orban-0719880a351a5ef0763ae6a623a7798b.

Trade and investment: China’s gateway to EU markets

Over the past decade, as Hungary’s partnership with China has grown increasingly close, bilateral trade and investment have expanded significantly. The Orbán government has actively positioned Hungary as China’s regional gateway to EU markets and has sought to embed the country within China’s global supply chains.14Matt Boyse, “China Increasing Its Bets on Hungary and Serbia,” Geopolitical Intelligence Services, July 22, 2024, https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/china-interests-central-europe/. In 2024, trade between Hungary and China reached $16.2 billion—a 93 percent increase from 2013, when it stood at roughly $8.4 billion.15Tianyi Xiao, “China-Hungary Bilateral Relations: Trade and Investment Outlook,” China Briefing, June 27, 2024, https://www.china-briefing.com/news/china-hungary-bilateral-relations-trade-and-investment-outlook; “China and Hungary,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs, People’s Republic of China, 2024, https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/gjhdq_665435/3265_665445/3175_664570/.

Hungary’s cooperation with China also extends to infrastructure development. In 2015, Hungary became the first EU member state to join China’s BRI. Its flagship project is the Belgrade-Budapest high-speed railway, envisioned as a key segment of the BRI corridor connecting the Chinese-owned port of Piraeus in Greece to Duisburg, Germany.16Zoltán Kiszelly, “China’s European Bridgehead,” Geopolitical Intelligence Services, June 26, 2025, https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/china-hungary. The construction of the railway has been contracted to Chinese and Hungarian companies since 2014, but it has yet to be completed.17Ibid. The project has proven controversial in Hungary, where the railway’s domestic segment is being built by a company owned by one of Orbán’s childhood friends. The Serbian section has drawn even greater criticism following the deadly collapse of the Chinese-renovated Novi Sad train station in November 2024, which sparked nationwide anti-government protests in Serbia.18Jens Kastner, “Botched Belt and Road Project Triggers Political Crisis in Serbia,” Nikkei Asia, December 19, 2024, https://asia.nikkei.com/spotlight/belt-and-road/botched-belt-and-road-project-triggers-political-crisis-in-serbia.

During Xi Jinping’s May 2024 visit, Beijing and Budapest agreed on two new railway projects: the V0 rail ring, designed to draw international transit freight traffic away from the Budapest bottleneck, and a new rail link connecting the country’s main aviation hub, Ferenc Liszt International Airport, with the capital. Xi and Orbán also agreed that Chinese companies would build “the most modern, largest, safest, and fastest border crossing between Hungary and Serbia,” near the town of Röszke.19Ádám Bráder, “Historic Visit of Chinese President Xi Jinping to Hungary Yields Eighteen Significant Agreements,” Hungarian Conservative, May 10, 2024, https://www.hungarianconservative.com/articles/current/historic_visit_bilateral_agreements_china_hungary_airport_railway_oil-pipeline_szijjarto. If completed, it would mark the first instance of a Chinese firm modernizing a border crossing within the EU’s Schengen Area.

Investment has been another key pillar of Hungary-China cooperation. In 2023, 44 percent of all Chinese FDI directed toward the EU flowed into Hungary.20“Tavaly az Európába Irányuló Kínai Beruházások 44 Százaléka Magyarországra Érkezett,” Kormany, November 26, 2024, https://kormany.hu/hirek/tavaly-az-europaba-iranyulo-kinai-beruhazasok-44-szazaleka-magyarorszagra-erkezett. Since 2020, China has been Hungary’s largest source of foreign investment.21Xiao, “China-Hungary Bilateral Relations.” Beginning in 2022, several Chinese industrial giants—including Contemporary Amperex Technology Co. Ltd. (CATL), BYD, EVE Energy, and XINWANDA—have established major factories in Hungary, especially in EV and EV battery production. CATL’s battery plant is considered the largest single investment in Hungary’s history.22Ibid.

BYD first opened an electric bus factory in Hungary in 2017, built a nearly $5 billion EV production base in Szeged in 2024, and relocated its European headquarters from the Netherlands to Hungary in 2025 after signing a strategic cooperation agreement with the Hungarian government.23“BYD Moves European HQ to Hungary, Sets up €250mn Business and Development,” BNE Intellinews, May 16, 2025, https://www.intellinews.com/byd-moves-european-hq-to-hungary-sets-up-250mn-business-and-development-381453. However, China’s industrial expansion—especially its EV battery factories—has provoked controversy and opposition in Hungary, fueled by concerns over an influx of foreign workers, environmental degradation, and perceptions of “Chinese colonization.” Critics point to generous government subsidies, regulatory exemptions, and a lack of transparency or local benefit surrounding these Chinese investments.24Amerikai Népszava, “Nem Leszünk Kínai Gyarmat, Mert Már az Vagyunk,” Amerikai Népszava, May 7, 2024, https://nepszava.us/nem-leszunk-kinai-gyarmat-mert-mar-az-vagyunk; “Szegedbe is Belemar a Kínai Gyarmatosítás,” Greenfo, https://greenfo.hu/hir/szegedbe-is-belemar-a-kinai-gyarmatositas/; Besenyei Zsolt, “Azt Nem Ígérték, Hogy Kínai és Orosz Gyarmat se Leszünk,” Szeged.hu, April 15, 2024, https://szeged.hu/cikk/azt-nem-igertek-hogy-kinai-es-orosz-gyarmat-se-leszunk-besenyei-zsolt-jegyzete; Karl Harenbrock, “Behind China’s Massive Bet on Hungary,” Deutsche Welle, YouTube video, July 4, 2024, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fiCo0BASdkA.

Hungary and China have also deepened their financial ties over the past decade. Although the Bank of China has operated in Hungary since the mid-1980s, its Budapest branch received official legal authority in 2015 and was designated as the bank’s Central and Eastern European headquarters.25“Interview: Hungary Looks Forward to Further Cooperation with China, Official Says,” Xinhua News Agency, May 5, 2024, https://eng.yidaiyilu.gov.cn/p/0DG0579C.html. In 2014, the People’s Bank of China and the Central Bank of Hungary signed an agreement expanding the Renminbi Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor pilot program—allowing select foreign investors to invest directly in China’s bond and equity markets—to Hungary.26Choo Lye Tan, “The Renminbi Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor Program—Opportunities and Challenges for International Investors Interested in Direct Access to PRC Securities with Offshore Renminbi,” Investment Lawyer 21, 8 (2014), https://files.klgates.com/files/publication/a3986722-a0c2-436c-ad83-5474625d86d7/presentation/publicationattachment/04e0d5b1-d0f6-4bb1-a5a0-637065d6f6e9/the_renminbi_qualified_foreign_institutional%20investor_program.pdf. Moreover, the Budapest branch of the Bank of China was designated as the region’s first “RMB clearing bank.”

In 2016, Hungary became the first EU country to issue “panda bonds”—bonds denominated in renminbi (RMB) and issued by a non-Chinese borrower in China—to attract Chinese investors and diversify funding sources.27“Panda Bonds Explained: Understanding China’s Growing Bond Market,” Deutsche Bank, February 28, 2025, https://www.db.com/news/detail/20250228-panda-bonds-explained-understanding-china-s-growing-bond-market?language_id=1. After an initial RMB 1 billion tranche, total issuance rose to RMB 2 billion in 2018, followed by the first-ever tranche of “green panda bonds” in 2021. In 2022, Hungary issued an additional RMB 2 billion tranche.28“China and Hungary”; “Long-Term Cooperation between MBH Bank and Bank of China in Sight,” MTI-Hungary Today, September 27, 2024, https://hungarytoday.hu/long-term-cooperation-between-mbh-bank-and-bank-of-china-in-sight/. Because of its high public debt and restricted access to EU cohesion and reconstruction funds, Hungary took out a record-setting loan from China in 2024. The $1.17 billion loan—the largest in Hungary’s history—was intended to finance infrastructure and energy projects and was provided jointly by the China Development Bank, the Export-Import Bank of China, and the Bank of China’s Budapest branch. The deal has sparked controversy due to the government’s classification of its terms.29Csongor Körömi, “Hungary Quietly Takes €1B Loan from Chinese Banks,” Politico, July 25, 2024, https://www.politico.eu/article/budapest-hungary-took-1-billion-loan-chinese-banks-peter-szijjarto/.

Technology: Defying EU and US pressure

Hungary’s cooperation with China in technology has intensified significantly over the past decade and, like its economic and security relations, has often run counter to EU and transatlantic policy priorities. Budapest has rejected calls from European nations and the United States to exclude Chinese firms from its telecommunications and critical infrastructure. Instead, it has welcomed Huawei’s investments throughout its telecommunications sector, including in the rollout of 5G infrastructure.

Huawei opened a research and development hub in Budapest in 2020 and, in 2023, signed a strategic cooperation agreement with 4iG—a company closely linked to the Orbán government—to develop 5G, fixed-line, and mobile networks across Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe.30“Hungary MOU with Huawei Angers US,” Central European Times, November 2, 2023, https://centraleuropeantimes.com/hungary-mou-with-huawei-angers-us/. Huawei has also established a data center in Hungary serving Chinese and other Asian firms operating in the region.

Moreover, the Orbán government has expressed interest in Huawei-made facial recognition technology powered by artificial intelligence and has purchased surveillance cameras from Hikvision, a Chinese state-owned company. These actions have sparked widespread criticism amid fears that the Hungarian government could use such tools to monitor anti-Orbán protestors.31Kiszelly, “China’s European Bridgehead”; Sebestyén Hompot, “Orbán Doubles Down on Turning Hungary into a Regional Hub of Chinese Influence,” China Observers in Central and Eastern Europe, November 9, 2023, https://chinaobservers.eu/orban-doubles-down-on-turning-hungary-into-a-regional-hub-of-chinese-influence; “Chinese-Made Surveillance Cameras Are Spreading Across Eastern Europe, Despite Security Concerns,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, May 6, 2024, https://www.rferl.org/a/china-surveillance-cameras-europe-dahua-hikvision/32930737.html. The United States has repeatedly raised concerns about this cooperation—both during the first Trump administration and the Biden administration.32Tamara Gyurkó, “Hungary Cooperating with Chinese Huawei: Biden Cabinet Outraged,” Daily News Hungary, October 31, 2023, https://dailynewshungary.com/hungarys-cooperating-with-chinese-huawei-biden-cabinet-outraged. Defying allied pressure and ignoring security risks, Hungary has continued to double down on its partnership with Huawei.33Hompot, “Orbán Doubles Down on Turning Hungary into a Regional Hub of Chinese Influence.”

The Orbán government has also permitted China to penetrate Hungary’s critical infrastructure. Beyond allowing Chinese firms to build railway networks and border crossings, Orbán and Xi agreed in May 2024 to cooperate on “the full spectrum of the nuclear industry.”34“Hungary and China Sign Nuclear Energy Cooperation Agreement,” World Nuclear News, May 10, 2024, https://world-nuclear-news.org/articles/hungary-and-china-sign-nuclear-cooperation-agreeme; David Rogers, “China, Hungary Agree Rail Schemes and ‘Full-Spectrum’ Nuclear Cooperation,” Global Construction Review, May 15, 2024, https://www.globalconstructionreview.com/china-hungary-agree-rail-schemes-and-full-spectrum-nuclear-cooperation. Such cooperation contradicts EU and US policy and prompted the Biden administration to openly criticize the partnership. The second Trump administration, which has maintained a friendly rapport with Orbán, similarly opposed Hungary granting China broad access to its telecommunications networks and critical infrastructure. In April 2025, the Trump administration’s Chargé d’Affaires in Hungary, Robert Palladino, issued a rare warning to the Orbán government: “President Trump is clear: China poses strategic challenges to the United States and our allies, challenges that require vigilance, transparency, and unity… Countering China’s malign influences is a top priority… Whether it’s about digital infrastructure, technology transfer, or critical sectors, we encourage all of our partners to make choices that support long-term sovereignty.”35US Embassy Budapest, “Chargé d’Affaires Robert Palladino’s Remarks at the Central European Summit,” YouTube video, April 15, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C__usttFASw.

Security: Intelligence cooperation and controversial agreements

As part of its grand strategic alignment, the Orbán government has established a security partnership with China, making Hungary the only EU and NATO country to do so—directly contradicting EU and transatlantic policy, which classifies China as a systemic rival. Hungary hosted the 2012 founding meeting of the Cooperation between China and Central and Eastern European Countries, formerly known as the “16+1” and “17+1” format. While other Baltic states withdrew from the grouping and Czechia and Romania became inactive following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Hungary remains a key proponent. The Orbán government regularly echoes Chinese talking points in EU and NATO discussions and vetoes resolutions critical of Beijing’s domestic or international conduct.36Panyi, “Hungary in the Midst of a U.S.-Huawei War”; von der Burchard and Barigazzi, “Germany Slams Hungary for Blocking EU Criticism of China on Hong Kong.” At the beginning of Hungary’s EU Presidency in July 2024, Orbán openly defied EU, NATO, and US positions by embarking on a series of “peace missions” related to the Ukraine war, including a visit to Beijing where he endorsed Xi Jinping’s peace plan.37Zoltán Fehér, “‘What Will NATO Leaders Make of Orbán’s ‘Peace Missions?’ Live Expertise Blog on the Washington NATO Summit,” Atlantic Council, July 10, 2024, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/live-expertise-and-behind-the-scenes-insight-as-nato-leaders-gather-at-the-washington-summit/#feher-hungary-orban-visits; Jon Jackson, “NATO Country Leader Endorses China’s Peace Plan for Russia-Ukraine War,” Newsweek, May 9, 2024, https://www.newsweek.com/nato-country-leader-endorses-chinas-peace-plan-russia-ukraine-war-1899102.

Hungary’s security relationship with China extends beyond political alignment and rhetoric. In 2022, human rights organizations uncovered that the country is hosting China-operated “overseas police service stations,” tasked with providing “administrative support” for Chinese citizens in Hungary and pressuring them to return to the mainland.38Akos Keller-Alant, Mila Manojlovic, and Reid Standish, “Reports Of China’s Overseas ‘Police Stations’ Spark Controversy, Denial in Hungary And Serbia,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, November 9, 2022, https://www.rferl.org/a/reports-china-policestations-controversy-denial-hungary-serbia/32122899.html; “110 Overseas: 230,000 Chinese ‘Persuaded to Return,’” Safeguard Defenders, September 12, 2022, https://safeguarddefenders.com/en/blog/110-overseas-230000-chinese-persuaded-return. In February 2024, the two countries signed a security cooperation agreement allowing Chinese police officers to patrol alongside Hungarian law enforcement—raising concerns that Beijing’s influence in this area could deepen further.39Joseph Bebel, “Extradition Treaty Signals Beijing’s Wider Designs in Hungary,” Eurasia Daily Monitor, Jamestown Foundation, September 4, 2025, https://jamestown.org/program/extradition-treaty-signals-beijings-wider-designs-in-hungary; Liz Lee and Ryan Woo, “In Unusual Move, China Offers to Back Hungary in Security Matters,” Reuters, February 20, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/unusual-move-china-offers-back-hungary-security-matters-2024-02-19; Filip Jirouš, “PRC Exploitation of Russian Intelligence Networks in Europe,” China Brief 24, 8 (2024), https://jamestown.org/program/prc-exploitation-of-russian-intelligence-networks-in-europe. China’s extensive and often secret security agreements, combined with the spread of overseas police stations, have sparked fears that Chinese officers in Hungary might not only handle routine administrative tasks but also surveil Chinese citizens, pursue dissidents, and potentially even monitor Hungarian opposition.40Bebel, “Extradition Treaty Signals Beijing’s Wider Designs in Hungary.”

Reports that Hungary and China are close to concluding an extradition agreement have intensified these concerns, as have signs of expanded Chinese intelligence activities in Hungary.41Jakub Janda and Richard Kraemer, “Orban’s Hungary: A Russia and China Proxy Weakening Europe,” European Values Center for Security Policy, December 8, 2021, 14, https://europeanvalues.cz/en/orbans-hungary-a-russia-and-china-proxy-weakening-europe. Investigative journalists have revealed that the Chinese Communist Party’s external intelligence wing, the United Front Work Department (UFWD), is active in Hungary42Kamilla Marton, “How China’s United Front Extends Its Influence in Hungary,” Direkt36, October 5, 2024, https://vsquare.org/china-ccp-united-front-influence-hungary.—and that one of its recent operations involved the Fudan Hungary project,43Ibid. which aimed to establish a new campus of China’s Fudan University in Budapest. Ironically, while UFWD assets sought to quell local opposition, the suspicion that the campus would serve as a cover for Chinese intelligence agents fueled widespread protest and eventually forced the Hungarian government to abandon the project in 2021.44Ágota Révész, “The Pandora’s Box of Fudan Hungary,” Daedalus 153, 2 (2024), 207–216, https://direct.mit.edu/daed/article/153/2/207/121264/The-Pandora-s-Box-of-Fudan-Hungary.

Hungary’s alignment with the EU’s China policy

Among EU member states, Hungary’s China policy is the most divergent from Brussels’ overall approach. The country seeks deeper engagement with China in trade, investment, technology, and security, without the guardrails the EU imposes to mitigate economic and national security risks. Moreover, Hungary actively opposes EU efforts to balance and de-risk relations with China, often working to undermine and reverse these policies.

During Xi Jinping’s May 2024 visit, Orbán pledged to advance closer EU-China relations and roll back EU de-risking measures. During Hungary’s EU Presidency (July-December 2024), he criticized EU tariffs on Chinese EVs as an “economic cold war”45Justin Spike, “EU Tariffs on Chinese Electric Vehicles Are Part of an ‘Economic Cold War,’ Hungary’s Orbán Says,” Associated Press, October 4, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/hungary-orban-eu-china-electric-vehicles-b255691c021fb901ceb2f1563e3a4346. and used Hungary’s veto power to block EU statements and decisions critical of China on Hong Kong, the Uyghurs in Xinjiang, Taiwan, and the South China Sea.46Samuel Dempsey, “The Sino-Hungarian Relationship’s Effects on the EU and NATO,” Blue Europe, August 2, 2024, https://www.blue-europe.eu/analysis-en/short-analysis/the-sino-hungarian-relationships-effects-on-the-eu-and-nato; Ramses A. Wessel and Viktor Szép, “The Implementation of Article 31 of the Treaty on European Union and the Use of Qualified Majority,” European Parliament, November 11, 2022, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/IPOL_STU(2022)739139. According to Andrzej Sadecki, “while Budapest’s limited political clout means it could not completely stop the EU’s de-risking approach to China or block increased tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles, Beijing has benefited from EU disunity and Orbán had been one of its key proxies.”47Andrzej Sadecki, “Hungary’s Orbán Walks US-China Tightrope,” Center for European Policy Analysis, April 3, 2025,

https://cepa.org/article/hungarys-orban-walks-us-china-tightrope.

For more than a decade, Hungary has consistently advanced Beijing’s interests within the EU, opposing de-risking and balancing measures. In doing so, it has partially undermined EU cohesion and its alignment with the United States on China-related challenges.

Conclusion

In the three and a half decades since 1989, Hungary has transformed from a former Soviet bloc frontrunner in democratization and Euro-Atlantic integration into an electoral authoritarian country and China’s and Russia’s main ally within the EU and NATO. Under Viktor Orbán, the country has built a grand strategic alliance with Beijing and become the flagbearer of China’s interests, consistently blocking EU action addressing China’s challenges across all domains.

Hungary has developed a close economic relationship with China, facilitating substantial Chinese investments in EV and battery production, telecommunications, IT, and financial services. The country has welcomed Chinese companies like Huawei and ZTE into the telecommunications sector and allowed BRI projects to penetrate its critical infrastructure, from railways to the nuclear industry. Budapest has also aligned with Beijing on security matters. It is hosting Chinese overseas police stations and a significant and growing Chinese intelligence presence—and it has endorsed Xi Jinping’s Ukraine peace plan.

Not only has Budapest failed to align with EU China policies, but it has also actively sought to block EU-level de-risking and undermine European unity in addressing China’s strategic challenges.

About the author

Related Content

Explore the programs

The Global China Hub tracks Beijing’s actions and their global impacts, assessing China’s rise from multiple angles and identifying emerging China policy challenges. The Hub leverages its network of China experts around the world to generate actionable recommendations for policymakers in Washington and beyond.

The Europe Center promotes leadership, strategies, and analysis to ensure a strong, ambitious, and forward-looking transatlantic relationship.

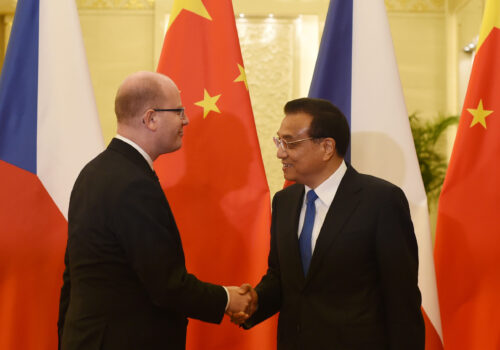

Image: Hungary's Prime Minister Viktor Orban (2nd L) and China's President Xi Jinping (2nd R) lead their delegations during a meeting at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, February 13, 2014. REUTERS/Rolex Dela Pena/Pool (CHINA - Tags: POLITICS)