An introduction to the Freedom Online Coalition

Understanding the first ten years of the world’s democratic tech alliance

Democratic and authoritarian nations are in a global competition for the digital world, amid a bid to renew or remake the world order. On one side is the long-standing global norm that the Internet is a global good, governed by a multistakeholder community and designed to be free, open, secure, and interoperable. On the other side is a model antithetical to the universal rights and democratic norms around which the United States and its allies organize. That authoritarian model advances a version of the Internet in which states leverage technology to shatter citizen expectations of privacy, free expression, and assembly.

Core to the authoritarian strategy are efforts to drive a wedge between the historically effective alliance of democratic nations working collectively to ensure everyone, everywhere can benefit from a digital ecosystem in which basic rights are embedded. The growing variance in approach between democratic countries in governing their own use of technology only serves to broaden that wedge. As the authoritarian model spreads, it is politically and practically shifting the online experience of billions of people, including those within democracies. The stability and sustainability of a free, open, secure, and interoperable Internet relies on democracies’ ability to rebuke these efforts and defend the Internet as a key infrastructure to advance human rights. In addition to countering authoritarian repression abroad, this includes grounding their own use of technology in democratic principles and working to prevent emerging innovations from being misused to undermine human rights at home and around the world. A failure to do so will only accelerate the authoritarian capture of the Internet, and cause a global loss in access to speech, expression, and prosperity.

It is no surprise, then, that policymakers increasingly call for “democratic tech alliances” on everything from supply chains to emerging technology to global Internet freedom. This has renewed attention to the Freedom Online Coalition (FOC), which comprises thirty-five member countries committed to advancing Internet freedom and human rights online. The FOC’s mission is more relevant now than ever in its eleven-year history, providing opportunities for its member states to

- coordinate public and private diplomatic action in response to threats to democracy and human rights online;

- collaborate in multistakeholder and multilateral forums to bolster human-rights-aligned norms and standards for the digital ecosystem; and

- maintain a trusted space for collaboration with civil-society and industry actors that serves as a center of gravity for joint strategic action.

At the same time, the FOC as an institution is at an inflection point. As democracies seek mechanisms to drive collaboration and action in an increasingly adversarial global space, FOC member countries have an opportunity to strengthen, clarify, and focus energy through the coalition. Doing so will require members to address long-standing debates related to its scope of work, incentives, and impact in international forums.

This primer on the FOC is intended to serve as an introduction to the entity, summarizing its structure and development over time. In the final section, this introduction provides an overview of the key tensions that member countries will need to address to make the coalition more effective, credible, and durable.

The document is based on a literature review of publicly available information on the FOC website, including the coalition’s descriptions of its activities, meeting minutes, declarations, and other materials related to convenings and workstreams. Additionally, DFRLab staff interviewed civil-society leaders from around the world who have worked in partnership with the coalition, and consulted with others present during the FOC’s founding and various iterations of its development. Staff also consulted former US government and other member-nation officials, and contacted the FOC Support Unit for information about its structure, budget, and workstreams.

What is the Freedom Online Coalition?

The Freedom Online Coalition is a multilateral group of thirty-five countries that coordinates diplomatic discussion and possible response on salient issues involving Internet freedom and digital rights. The central aim of the FOC is to ensure “that the human rights that people have offline enjoy the same protection online.”1“Freedom Online: Joint Action for Free Expression on the Internet,” Freedom Online Coalition, December 8–9, 2011. The coalition aims to protect Internet freedom and ensure that digital rights are a priority in policymaking around the world. At its founding in 2011, the FOC focused predominantly on organizing diplomatic responses to threats to freedom of expression and association online, including threats related to content filtering, network disruptions, surveillance technology, and censorship. As the impacts of technology and the Internet become increasingly central in international and political discourse, the FOC has also considered the rights implications of cybersecurity, digital authoritarianism, and digital equality and access. The FOC has also sought to engage more formally with the private sector and civil society through thematic working groups, the FOC Advisory Network, and periodic external-stakeholder engagements.

Origins of the Coalition

Throughout the early twenty-first century, Internet connectivity increased around the world, as did its impact on political expression and attitudes. While citizens had started to leverage technology to organize protest movements as early as Iran’s 2009 Green Movement, the 2011 Arab Spring captivated the attention of much of the world and thrust social media platforms to center stage. As a result, governments and companies alike scrambled to make sense of the increasingly central role the Internet was playing in geopolitics. As activists deployed digital tools to organize protests and broadcast the subsequent brutal crackdowns, authoritarian governments sought to censor content, surveil citizens, or shutter open platforms altogether to reassert government control. Amid this dangerous match between citizens and authoritarian states, democratic governments explored how best to support those seeking to extend universal rights to and through the Internet.

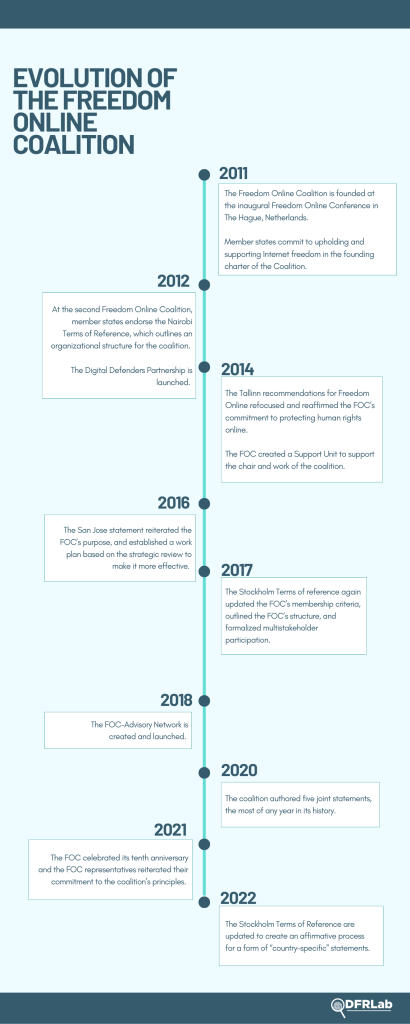

In the United States, the nascent idea of “Internet Freedom” percolated as a foreign policy priority, with then Secretary of State Hillary Clinton leading a dedicated Internet freedom agenda. This new US government focus was based principally on values Clinton set out in a January 2010 address, notably promising to increase funding and diplomatic engagement on the issue set, and to seek opportunities to partner with other governments to do the same.2Hilary Rodham Clinton, “Remarks on Internet Freedom,” (remarks at the Newseum, Washington, DC, January 21, 2010), https://2009-2017.state.gov/secretary/20092013clinton/rm/2010/01/135519.htm In the following years, the US government created the Open Technology Fund to develop anti-surveillance and anti-censorship tools for activists in authoritarian states, and secured bipartisan resources from the US Congress for the State Department’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor to support those on the front lines of Internet freedom globally.3“About: Open Technology Fund,” Open Technology Fund, last visited November 9, 2022, https://www.opentech.fund/about/ It was in this context that the United States joined thirteen other countries in the Netherlands on December 8, 2011, to formally launch the FOC at the inaugural Freedom Online Conference, with the seemingly simple commitment to “engage together to protect human rights online.”4“Freedom Online: Joint Action for Free Expression on the Internet.” The founding members of the FOC include Austria, Canada, Costa Rica, the Czech Republic, Finland, France, Estonia, Ghana, Ireland, Kenya, Latvia, the Republic of Maldives, Mexico, Mongolia, the Netherlands, Sweden, Tunisia, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Current Coalition structure and operations

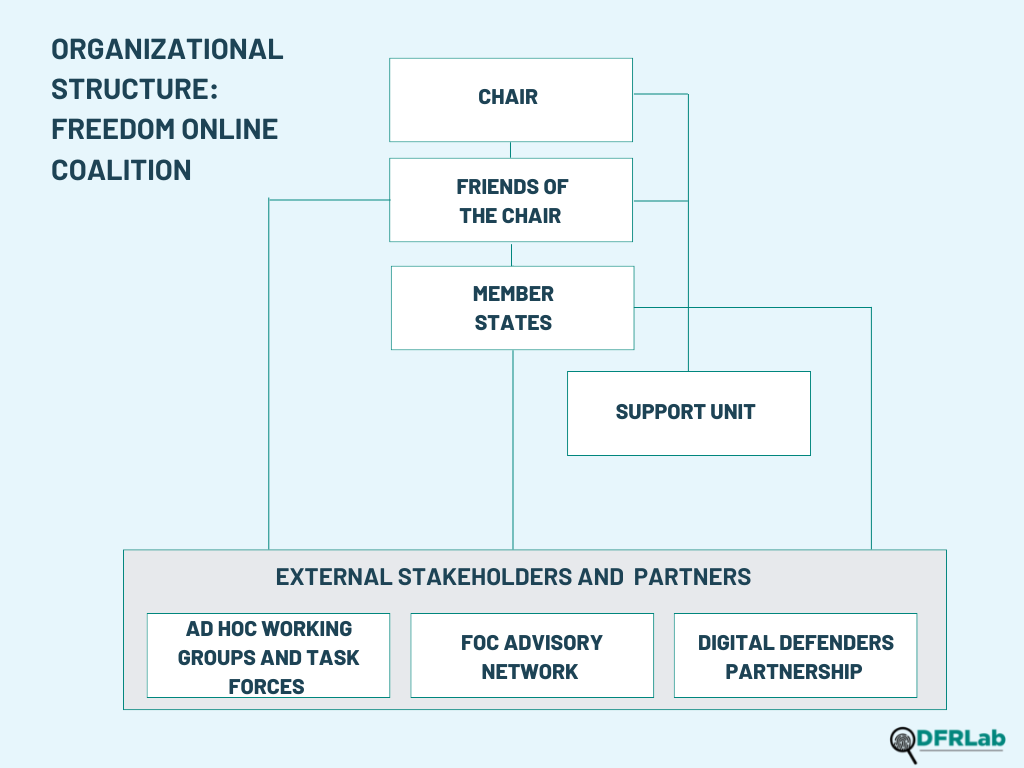

The FOC is not a legal entity, and member contributions are made on a voluntary basis. The official structure and procedure for the coalition have been developed over time and are still somewhat ad hoc.5“Structure, Freedom Online Coalition,” Freedom Online Coalition, last visited November 9, 2022, http://freedomonlinecoalition.com/structure The FOC is led each year by a different country chair, which is selected after members state their interest and the full coalition votes on the slate. The chair is supported by the “Friends of the Chair,” a rotating group of FOC member states intended to ensure continuity and consistency through the yearly transitions.6Ibid. Current “Friends of the Chair” include Canada (2022 chair of the FOC), Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Ghana, the Netherlands, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States Each year, the chair of the FOC assumes responsibility for coordinating the coalition, setting its agenda, providing diplomatic support, and hosting the Freedom Online Conference. Annually since 2017, the FOC has published its goals in a program of action that outlines substantive and organizational priorities for the upcoming year.“7Aims and Priorities, Freedom Online Coalition,” Freedom Online Coalition, last visited November 9, 2022, http://freedomonlinecoalition.com/aims-and-priorities. The coalition makes key decisions at annual conferences, on the sidelines of international convenings, and through continued communications throughout the year.

In addition to its core diplomatic-coordination role, the FOC also conducts outreach and programming with civil society and industry. The FOC advisory network (FOC-AN), created in 2017 and launched in 2018, is a group of nongovernmental stakeholders that provides FOC member governments with advice and serves as the main mechanism for the FOC to receive the insights of civil society and the broader multistakeholder community.8“Advisory Network, Freedom Online Coalition,” Freedom Online Coalition, last visited November 9, 2022, http://freedomonlinecoalition.com/advisory-network. The FOC also currently operates three task forces and a working group, each of which includes government, industry, and civil-society representatives: the Task Force on Artificial Intelligence and Human Rights; the Task Force on Digital Equality; the Task Force on Internet Shutdowns; and the Silicon Valley Working Group, which is particularly focused on engaging industry in the FOC’s work.

The current criteria to become an FOC member state are laid out in the Stockholm Terms of Reference, which were adopted in 2017. They require countries to demonstrate a strong commitment to human rights and Internet freedom—both domestically and through their foreign policy—as well as to be members in good standing of other democracy-focused multistakeholder and intergovernmental organizations and forums.“9Stockholm Terms of Reference of the Freedom Online Coalition,” Freedom Online Coalition, May 16, 2017, https://freedomonlinecoalition.com/document/the-stockholm-terms-of-reference/. To be removed from the coalition, a country can voluntarily withdraw, or its membership can be terminated following a recommendation from the chair or “Friend of the Chair” and a review of the government’s actions. After such a recommendation, a case is prepared and sent to the full FOC, and, if there are no objections, the member is terminated from the coalition. This procedure has never been used.

The chair and “Friends of the Chair” effectively function as the rotating FOC secretariat, which is staffed by a Support Unit housed at Global Partners Digital (GPD), based in London.10“Global Partners Digital,” Global Partners Digital, last visited November 9, 2022, https://www.gp-digital.org. The “Friends of the Chair” convene on a monthly basis, and the minutes of these calls are published at: “Friends of the Chair Monthly Call #1,” Freedom Online Coalition, last visited November 9, 2022, https://freedomonlinecoalition.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Minutes-from-the-Friends-of-the-Chair-Call-1-January-1.pdf. This support function was not created until 2014, and the funding, personnel, structure, ownership, and terms of reference are a patchwork that developed over the intervening years. GPD was selected by the FOC, in part, because it was already engaged in the digital-rights space and had existing funding through the US Department of State. The Support Unit is run by the executive director of GPD and three dedicated staff members. Its primary responsibilities are serving as the main point of contact for FOC members, organizing member convenings and conference calls, communicating with the FOC Advisory Network, supporting task-force communications, maintaining the FOC internal listserv, providing substantive guidance when appropriate, and administering the FOC website and social media accounts.

Funding for the Support Unit fluctuates on an annual basis, dependent on voluntary contributions from member states via flexible grant agreements.11Member states that contributed to the Support Unit’s 2022–2023 budget include Australia, Canada, Estonia, Finland, Ireland, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and the United States. The Support Unit’s funding has steadily increased over the past five years, with a budget of just over $625,000 in 2022. The Support Unit reports against the requirements of each individual grant signed with the respective FOC members, and its day-to-day activities are mandated by an internal program of action developed in partnership with the chair and “Friends of the Chair” cohort. The Support Unit then reports against this broader program of action with updates on the funding for its own operations, as well as for discrete projects and efforts of the FOC more broadly. Noting concerns around the unpredictability of this funding arrangement, the 2017 Stockholm Terms of Reference established a mandate for a voluntary member-state “Funding Coordination Group,” though it never became operational.

Coalition workstreams and outputs

Freedom Online Conference

The FOC’s most visible output is the Freedom Online Conference, which doubles as a stakeholder gathering and annual meeting of member states to discuss the state of digital rights and coordinate diplomatic strategies in response. Since the inaugural conference in The Hague in 2011, the FOC has held eight additional conferences: one every year except for 2017, 2019, and 2022.12The FOC did not have a chair in 2017 or 2020. The 2019 chair (Ghana) hosted its conference in February 2020. FOC Conferences are hosted by each year’s chair, and have been held in Nairobi, Kenya (2012); Tunis, Tunisia (2013); Tallinn, Estonia (2014); Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia (2015); San José, Costa Rica (2016); Berlin, Germany (2018); Accra, Ghana (early 2020 as part of Ghana’s 2019 chairship); and Helsinki, Finland (2021). Instead of a conference this year, FOC chair Canada opted to convene strategic retreats in Paris and Rome for member countries and the FOC-AN.

Each conference convenes FOC member countries, civil society, and industry for panels, workshops, and plenary sessions. The annual conference also serves as a platform to discuss organizational changes for the coalition itself, and is often used to initiate strategic reviews and to negotiate or publish new terms of reference, other official documents, or processes. A summary of these gatherings and the resulting statements can be found in Annex I.

In addition to the Freedom Online Conference, the FOC has, on occasion, convened on the sidelines of various international forums, including the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), the Internet Governance Forum (IGF), and the Stockholm Internet Forum.

Joint statements

The FOC publishes joint statements responding to challenges to Internet freedom. The FOC’s earliest statements stressed the importance of freedom of expression and compelled governments to protect it online. As the coalition evolved, it published joint statements on a wider range of topics related to digital rights, comprising Internet shutdowns and content filtering, disinformation, state surveillance, cybersecurity, and artificial intelligence. A list of these statements can be found in Annex II. The coalition as an entity has only once published a country-specific statement: in 2013, it condemned Internet legislation introduced in Vietnam that restricted access and limited online speech.“13FOC Joint Statement on The Socialist Republic of Vietnam’s Decree 72,” Freedom Online Coalition, August 2013, https://freedomonlinecoalition.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/FOC-Joint-Statement-on-The-Socialist-Republic-of-Vietnams-Decree-72.pdf. This statement led to significant debate within the coalition about the appropriateness of country-specific statements, due to sensitivities around complicating direct diplomatic relationships. Since then, the lack of direct government references in FOC statements has been a topic of debate, particularly as governments from Nigeria to Russia have moved to ban platforms or restrict Internet access in their countries.

In 2022, the Canadian government, as chair, led an effort to amend the Stockholm Terms of Reference to create a process for a form of “country-specific” statements—joint statements in which member states have the option of endorsing a statement critical of a named government, which is then distributed by the FOC. Additionally, the chair of the FOC can issue a “chair statement,” in which the chair drafts and issues a statement, and other member states have the option to endorse it. While the “country-specific” process has never been used, in March 2022, Canada issued a chair statement, condemning the Russian government for sponsoring and spreading disinformation to justify its invasion of Ukraine, with nineteen FOC member countries choosing to sign on.14“Statement on Behalf of the Chair of The Freedom Online Coalition: A Call to Action on State-Sponsored Disinformation in Ukraine,” Freedom Online Coalition, March 2, 2022, https://www.canada.ca/en/global-affairs/news/2022/03/statement-on-behalf-of-the-chair-of-the-freedom-online-coalition-a-call-to-action-on-state-sponsored-disinformation-in-ukraine.html.

Diplomatic coordination

Core to the FOC mission is diplomatic coordination on issues related to human rights online and Internet freedom. The result of this diplomatic coordination may not always be publicly evident. As the Internet freedom field grows, and digital issues are infused into an increasing number of policy areas, one of the more important functions of the FOC Support Unit is maintaining the list of contacts responsible within each government system for Internet freedom and digital issues, particularly as points of contact within diplomatic missions frequently rotate. These contacts and regular engagement across governments are a sure, but uneven, benefit. The coalition has faced regular calls to increase the relevance and effectiveness of its diplomatic engagement, but doing so will depend on the ability to call the right person at the right time on the right issue.

Engagement with the multistakeholder internet community

At its inception, multistakeholder engagement with the FOC was relatively open and unrestricted. Civil society participated at the annual conference and was encouraged to make recommendations for, and provide input on, joint statements. In recent years, the FOC formalized mechanisms to include civil society and industry in its work through the FOC-AN (discussed above) and Silicon Valley Working Group. The FOC-AN standardized civil-society engagement, and has also helped to narrow which individuals and organizations are able to regularly access the coalition.

Additionally, the coalition has long collaborated with the multistakeholder community through a mixture of working groups and task forces. Since its creation, the FOC has run a total of eight such efforts, focused on everything from cybersecurity to digital inclusion, with four currently running. The efficacy of these working groups has been mixed, with early efforts garnering a fair amount of participation. Over time, however, insufficient resourcing—and a lack of clear aims and outputs—led some early participants to disengage with the coalition. A common complaint has been a lack of clarity on what the expected outputs and impact of these working groups could or should be, and a disconnection from contentious and important policy issues actively under debate.

By way of example, in the wake of the Edward Snowden disclosures beginning in June 2013, civil society and FOC members leveraged the now sunset “Internet Free and Secure” working group to drive serious discussions about state surveillance, civil liberties, and human rights—including domestic and international stakeholders who do not often sit at the same tables. While the discussion was highly relevant, the lack of follow-on action or member-country attention to the group’s recommendations left some civil-society collaborators disillusioned with the coalition more broadly.15“Recommendations for Human Rights Based Approaches to Cybersecurity,” Internet Free & Secure Initiative, last visited November 9, 2022, https://freeandsecure.online/recommendations/.

Support to frontline defenders and the Internet freedom ecosystem

While there is yet to be a reliable and dedicated funding stream for the FOC itself, the coalition launched the Digital Defenders Partnership (DDP) fund in 2012, administered by the nonprofit Hivos.16“Digital Defenders Partnership,” Hivos, last visited November 9, 2022, https://hivos.org/program/digital-defenders-partnership/#:~:text=Digital%20Defenders%20Partnership%20(DDP)%20was,harm%20and%20mentorship%20and%20partnership. The stated purpose of the pooled fund is to support frontline digital defenders. The ministries of foreign affairs of Australia, Canada, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom, along with the Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA) and the US State Department, have contributed funding. Its current budget is 3.5 million euros through 2023. An exhaustive list of projects administered via the fund is not publicly available, though Hivos’s website cites implementation in Brazil, Yemen, and Russia.17Ibid.

Coalition changes over time

Since its formation in 2011, the FOC has been in an iterative cycle, adding new functions and support, debating impact, and assessing opportunities to strengthen the entity. After its creation in 2011, the founding members reconvened in 2012 in Nairobi, in an effort to reinforce global support for, and relevance of, the coalition. The resulting Nairobi Terms of Reference established the annual rotation of the chairmanship on a voluntary basis, outlined the responsibility of the chair to host the annual conference, and delineated criteria for new members wishing to join.“18Freedom Online Coalition (FOC) Terms of Reference,” Freedom Online Coalition, September 6, 2012, https://freedomonlinecoalition.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Nairobi-Terms-of-Reference.pdf. It also initiated a conversation about with what substantive issues the coalition might engage, created the Digital Defenders Partnership and rallied funding for it, and identified forums and opportunities for the FOC to drive its action beyond the yearly gathering.

In 2013, the group convened in Tunis, in a nod to one of the earlier Arab Spring countries in the midst of a democratic transition. There, it established three working groups: An Internet Free and Secure; Digital Development and Openness; and Privacy and Transparency Online.19“Ad Hoc Working Groups & Other Entities,” Freedom Online Coalition, last visited November 9, 2022, https://freedomonlinecoalition.com/ad-hoc-working-groups-task-forces. The purpose of the working groups was to facilitate ad hoc convenings outside of the Freedom Online Conference, focused on specific topics under the umbrella of Internet freedom. The working groups also brought new stakeholders into the fold, giving civil society and industry the ostensible opportunity to strategically advise FOC governments and shape both domestic and international outcomes. The mandates of the original three working groups officially ended in 2017.

In 2014, current events drove the agenda at the coalition’s fourth formal gathering in Tallinn, Estonia, stalling what had been steady momentum in building clarity and action around the group. The Snowden disclosures hit newsstands in June 2013, with thousands of classified documents leaking to the press over the following year, bringing to light the extent of the US government’s digital-surveillance practices.“20Snowden Revelations,” Lawfare, last visited November 9, 2022, https://www.lawfareblog.com/snowden-revelations. For an entity focused on governments restricting Internet access and human-rights abuses, accusations of one of its founding members advancing extraconstitutional surveillance through the Internet was an unavoidable earthquake and credibility challenge. That year’s “Recommendations for Freedom Online,” referred to as the Tallinn Agenda, doubled down on the coalition’s founding principles.21“Recommendations for Freedom Online,” Freedom Online Coalition, April 28, 2014, https://freedomonlinecoalition.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/FOC-recommendations-consensus.pdf. In addition to restating the coalition’s commitment to protect digital rights, it acknowledged the growing global concern around surveillance, and called on governments to establish strong domestic oversight of the deployment of such technologies.

Despite these foundational debates, FOC countries managed to advance organizational development at the Tallinn event, creating a secretariat and tapping GPD (as discussed above) to host the Support Unit, enabled through an increase of funding through an existing grant from the US government.

In 2015, Mongolia hosted the Freedom Online Conference in Ulaanbaatar (in a nod to growing concerns about China’s regional and global digital authoritarianism), where the coalition renewed the mandates of the original three working groups. In the wake of the 2014 disclosures, enthusiasm within the coalition waned, causing a change of focus to the need to reinvigorate and reform the wayward effort. Beyond featuring Mongolia’s leadership in a highly geopolitically contested region, the 2015 Ulaanbaatar conference’s primary contribution was the creation of an internal working group tasked with a strategic review of the organization. The strategic review was led by the United States and supported by the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and other member countries. The group contracted an outside expert to lead a concurrent external survey, the full results of which are included in the table at the end of this document.

The FOC published the results of that “external strategic review” at the 2016 conference in San José, Costa Rica, finding that, while there was still broad support for the coalition, member states saw a need to clarify the mandate of the FOC and identify clear overarching goals and outputs.“22Looking Back to Move Ahead: Freedom Online Coalition Strategic Review Outcome. Final Report and Recommendations of the FOC Strategic Review Working Group May 2015–October 16,” Freedom Online Coalition, October 17–18, 2016, https://freedomonlinecoalition.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/FOC-SRWG-Outcome-bundle_FINAL-1.pdf. Building on the results of the review, member states released the San José Statement, which reaffirmed the coalition’s core principles, and outlined a work plan to strengthen the FOC by increasing coherence among and expanding membership, improving the coalition’s and cross-regional coordination, and building external relationships.“23The San Jose Statement of the Freedom Online Coalition Regarding the Outcome of the 2016 Strategic Review,” Freedom Online Coalition, October 17–18, 2016.

The strategic review and subsequent conversations around it in San José laid the groundwork for one of the most significant sets of structural changes and formalization since the founding of the coalition, the revision of the Nairobi Terms of Reference. The coalition formalized these updates in what is called the Stockholm Terms of Reference.24“Stockholm Terms of Reference of the Freedom Online Coalition.” It is notable that this significant update occurred during one of the two years when the FOC had no chair. As there was no Freedom Online Conference that year, the updated terms of reference were adopted on the sidelines of the Stockholm Internet Forum in 2017. These new terms updated and expanded the structure of the coalition and clarified its workstreams. Notably, it expanded the procedure for a new member to join, established an “observer status,” and introduced a procedure for a government to either leave or have its membership revoked. Further, the Stockholm Terms of Reference established an organizational structure for the FOC that included outlining the responsibilities and election of the annual chair, establishing the “Friends of the Chair” structure, and clarifying working methods, including the process for issuing FOC statements.

The Stockholm Terms of Reference also restated the importance of the ad hoc working groups and created the FOC-AN, a new track for multistakeholder engagement, as discussed earlier. Finally, the new terms reframed the work of the FOC secretariat, formalizing the Support Unit as a neutral third party responsible for facilitating collaboration and coordinating convenings for FOC members.25The support unit remains housed at Global Digital Partners (GDP), with its most recent contract renewed in 2020. This more inward-looking work occurred in the months following the 2016 US presidential election, amid rising global concern with a proliferation of disinformation online and brazen foreign interference in core democratic processes. Amid the shift in US administrations, the FOC released a joint statement condemning state-sponsored disinformation in 2017.

In 2018, Germany took over the FOC chair and formally launched the FOC-AN, later hosting the Freedom Online Conference in Berlin. In 2019, during Ghana’s term as chair, the FOC created a limited one-year task force on “Cybersecurity and Human Rights.”26“Ad Hoc Working Groups & Other Entities.” Ghana hosted its conference early the following year in Accra with the theme of “Achieving a Common Vision for Internet Freedom,” which did not advance any organizational changes.27Ibid. FOC members released a joint statement on digital equality at the Accra conference, after which the FOC established a task force focused on bridging the digital divide and on topics of diversity, equity, and inclusion more broadly. Despite lacking a chair from March 2020 until January 2021, the FOC in that same time period established a Task Force on Artificial Intelligence and Human Rights and issued three joint statements on topics ranging from COVID-19’s impact on Internet freedom to disinformation and artificial intelligence. This was the highest rate of statement releases in the coalition’s history.

Finland took over as chair in 2021 as the FOC celebrated its tenth anniversary. That year’s Helsinki Declaration restated the group’s commitment to the protection of digital rights a decade on.28“FOC 10th Anniversary Helsinki Declaration—Towards a Rules-based, Democratic and Digitally Inclusive World,” Freedom Online Coalition, December 2–3, 2021, https://freedomonlinecoalition.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/FOC-10th-Anniversary-Helsinki-Declaration-Towards-a-Rules-based-Democratic-and-Digitally-Inclusive-World.pdf. The FOC also created a task force on Internet Shutdowns, as well as the Silicon Valley Working Group, which was intended to promote the work of the coalition and provide continuous engagement between parts of the tech industry and FOC governments.29Ibid.

As chair in 2022, adapting to COVID-19 concerns and accommodating the US-hosted virtual Summit for Democracy, Canada opted not to host a conference. Instead, it organized a strategic retreat for FOC members and the FOC-AN in Paris, and convened regional workshops on Internet freedom and digital rights across North America, Europe, the Middle East and North Africa, Asia-Pacific, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Latin America. The goal of these workshops is to update the Tallinn Agenda, with a new “Ottawa Agenda.”

Key issues and debates

As democracies and autocracies grapple over the future of the Internet, the Freedom Online Coalition is regularly raised as a conceptually important body with disappointing impact. The rationale for a venue for likeminded countries to coordinate shared approaches seems clear, and is often suggested anew by those seeking to address concerning trends in the digital world. Yet, the FOC is often overlooked or dismissed in those very conversations, leaving the coalition floating as yet another well-intended, poorly resourced international body, neither engaged seriously enough to be made central to an increasingly urgent issue nor fully disavowed to make way for something new.

This crisis of legitimacy is driven by a thematic set of perennial debates and questions that span the operational and substantive. For those newly engaging with the FOC, understanding these fault lines and strategic debates will be an important starting point. Below is an overarching summary of some of the key issues at play.

Mission and scope

The FOC was created originally to enable likeminded democracies to coordinate diplomatic action around state-based Internet repression. In its narrowest conception, this could be limited to coordinating individual country statements. In its most expansive conception, it could include growing the slate of countries proactively advancing a free, open, secure, and interoperable Internet. Divergent views on where on this spectrum the FOC should sit is one recurring debate that drives different strategies for the growth and focus of the coalition.

Another related debate centers on the tensions inherent in democratic nations organizing to call out the undemocratic actions of other countries, while sometimes replicating those same actions within their own borders. This dynamic was most evident in the wake of the Snowden disclosures, but it certainly extends to more recent questions around tech governance and regulation, and the significant variance between member-country domestic approaches. For some, this lack of willingness to “look within” undermines the worthiness and credibility of the coalition as a whole.

Funding and leadership

The FOC has never had a dedicated source of funding, and this lack of clear resourcing has implications for what it means to chair the group, what is achievable through it, and the ability to plan for more than a year at a time. This also impacts mechanisms for a support structure to carry out the work of the coalition through transitions.

The coalition is also impacted by an unequal and uncertain funding stream from each of its member states. Over the course of former US President Donald Trump’s administration, the FOC and other Internet freedom initiatives were disrupted by bipartisan reductions in US government funding. Some argue that this precariousness could be solved by an expansion of funding commitments from other members, while others feel that a broad reevaluation of funding strategy at large is vastly overdue.

Relatedly, with leadership of the FOC changing annually, there are limits to what “programs of action” can be carried through, with some arguing for longer terms and others believing the yearly rotating model better matches global examples.

Support and staffing

The FOC did not have a support mechanism until 2014, when the US government increased an existing grant to a United Kingdom-based organization to provide secretariat functions for the chair and FOC members. The expectations for that arrangement were more clearly articulated in 2017, but the setup remains somewhat ad hoc. Further, some have suggested that there is a conflict of interest in housing the Support Unit at an organization involved in the digital-rights space, saying that an organization that acts simultaneously as a key facilitator of the FOC and a civil-society advocate can wield asymmetric influence.

How a Support Unit is funded, housed, directed, and functions has major ramifications for the capacity and aims of the FOC itself. Many of the ideas for institutional learning, more intentional coordination and campaigns, greater support for working groups, task forces, and initiatives, and broader FOC strengthening depend on a stable and resourced Support Unit. The FOC is not the first organization to struggle with identifying funding for support mechanisms, but there is broad agreement that finding a sustainable model is essential.

Membership

From its inception, the FOC has been sensitive to the risk of appearing to be a club of Western countries lecturing the rest of the world. Member countries have sought to find regional balance in peers, but it is unquestionable that the group remains largely Western, with very few members from the “global majority.” While few argue that the FOC should not work to grow the community of countries aligned and coordinating on Internet freedom issues, how, when, and in what way to do so are still subjects of significant debate.

Simultaneously, there are others focused on ensuring FOC members are accountable to the principles of the coalition. Some are concerned that a sole focus on expanding national representation could result in a watering down of approach and substance and could detract from efforts to push existing countries to contend with difficult inconsistencies in their domestic and international approaches. For others, an expansion of membership is secondary to driving powerful countries to more successfully and seriously leverage their power to advance the cause of Internet freedom, whether diplomatically, or through foreign assistance or other means.

While none of these aims is necessarily contradictory with any other, optimizing for one or the other will lead to different approaches in funding, support, agenda, and mission—as well as affect the overall impact of the coalition itself.

Incentives

For those wishing to expand FOC membership, a common discussion focuses on what would incentivize countries to join. Are there streams of funding, support, or information sharing that could be made available only to members? Are there things the FOC can advance for member countries? For example, sharing good practices on digital public infrastructure or other digital-inclusion tools like advancing digital literacy? Simultaneously, are there any downsides for countries not joining the FOC? Those familiar with the FOC’s operations flag this as an important and underexamined element of the coalition’s potential approach.

Impact

Perhaps the single most important debate focuses on what success should look like for the FOC. With so many different visions for the coalition, and a real challenge to Internet freedom globally, it is no surprise few people are satisfied with the group’s achievements. The question of impact is closely tied to the debate around the FOC’s core mission and scope. For some, the FOC would be more impactful if it more successfully helped countries coordinate diplomatic responses behind the scenes. For others, success would include more forceful and collaborative public rebukes of antidemocratic actions.

Impact could also be demonstrated by the FOC’s ability to marshal resources and attention at high-impact moments such as the consideration of antidemocratic tech regulations, or situations like that in Russia in 2021, when the government coerced Apple and Google to remove a political-organizing app from their app stores.30Greg Miller and Joseph Menn, “Putin’s Prewar Moves Against U.S. Tech Giants Laid Groundwork for Crackdown on Free Expression,” Washington Post, March 12, 2022, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2022/03/12/russia-putin-google-apple-navalny. There is also the question of how the FOC advances its work, whether through loose coordination of member and nonmember states at international forums (such as the International Telecommunication Union or the UN General Assembly) or solely through its own coalition.

Finally, for some, the end goal of the coalition should be more countries and people buying into a proactive vision of Internet freedom based on international human-rights law and norms. In some ways, clarity on what the FOC is not focused on may be just as important as clarity on its mission and goals. There is a real risk that the FOC collapses under the weight of undifferentiated expectations. Clarifying and building agreement around FOC priorities, mandate, and scope is, therefore, essential.

This primer is based on a literature review of publicly available information on the FOC website, including the coalition’s descriptions of its activities, meeting minutes, declarations, and other documents related to convenings and workstreams. Additionally, DFRLab staff interviewed civil-society leaders from around the world who have worked in partnership with the coalition (at its inception, or through the FOC-AN or working groups), and consulted with others present during the founding and various iterations of the FOC’s development. Staff also consulted former US government and other member-nation officials and contacted the FOC Support Unit (Global Partners Digital) for information about its structure, budget, and workstreams.

The DFRLab is grateful to the individuals who contributed their expertise as we prepared this resource. Particular thanks are owed to Jochai Ben-Avie, Jessica Dheere, Eileen Donahoe, Verónica Ferrari, Katharine Kendrick, Mallory Knodel, Sarah Labowitz, Emma Llanso, Katherine Maher, Susan Morgan, Christopher Painter, Jason Pielemeier, Chris Riley, and Michael Samway.

Annex I: Timeline: Evolution of FOC Structure

Annex II: Timeline: FOC Joint Statements

Annex III: Glossary: FOC Terms

Coalition Chair: The chair of the coalition is responsible for coordinating the day-to-day meetings and strategy of the coalition, as well as providing diplomatic and political support for coalition convenings. Chairs may elect to host the Freedom Online Conference. The chairmanship rotates on an annual basis.

Digital Defenders Partnership (DDP): The Digital Defenders Partnership is a fund initiated by the FOC and managed by Hivos, which is intended to support digital-rights activists and human-rights defenders.

Freedom Online Conference: The Freedom Online Conference is a multistakeholder convening hosted semiannually by the coalition chair. The purpose of the conference is to advance the chair’s goals, laid out in the program of action, and facilitate discussions on Internet freedom issues relevant to the local context of the conference.

Friends of the Chair: The “Friends of the Chair” are a group of FOC members that provide support to the coalition chair. The purpose of this grouping is to ensure continuity between annual rotations of the chairmanship.

FOC Advisory Network (FOC-AN): The FOC Advisory Network is the formal mechanism for the FOC to engage with the broader multistakeholder Internet community and global civil society.

Joint Statement: Joint statements allow all member governments of the FOC to react together, and to prioritize issues related to Internet freedom. These statements include all members of the coalition.

- Country-Specific Statement: Country-specific statements are exceptional joint statements intended to call out the actions of a specific government that is threatening online freedoms. In this instance, the statements are opt in, and member countries may affirmatively choose to endorse them.

- Chair Statement: The chair of the FOC may issue a statement that is related to Internet freedom or that calls out the actions of a specific government. Member states may choose to opt in and endorse the statement of the chair.

Program of Action: The program of action is an agenda authored by the coalition chair and “Friends of the Chair” that sets the priorities for the coalition on an annual basis.

Support Unit: The Support Unit assists the coalition by providing administrative and logistical work to advance the goals laid out in the program of action.

Ad hoc working groups and task forces: Ad hoc working groups and task forces are established by the “Friends of the Chair” and are focused on a narrow substantive mandate. They typically comprise multistakeholder experts and are used to drive action and advise the coalition on issues related to their mandate.

Related content

The Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab) has operationalized the study of disinformation by exposing falsehoods and fake news, documenting human rights abuses, and building digital resilience worldwide.