Stealth, speed, and adaptability: The role of special operations forces in strategic competition

Table of contents

Background: What makes special operations forces “special”?

History of USSOF: SOF’s evolving purpose and how its history lends to competition today

- The creation of USSOF and its role in the twentieth century

- USSOF in the GWOT and the twenty-first century

- Public perceptions of USSOF

USSOF today in the context of strategic competition

- USSOF’s strengths applied to strategic competition

- I. Global and persistent engagement with allies and partners

- II. Gaining placement and access across the globe

- III. Operations across the competition continuum

- IV. At the cutting edge of capability development and employment

Executive summary

Today, the US Joint Force grapples with an array of security challenges that transcend traditional boundaries and cut across theaters and domains. US competitors—China and Russia—conduct military, information, economic, cyber, and diplomatic activities across the globe, from the Indo-Pacific and Europe to Africa, Latin America, Central Asia, and the Arctic. Managing strategic competition necessitates the United States taking proactive measures to counter malign activities and advance US strategic objectives across multiple theaters and domains.

US Special Operations Forces (USSOF) possess distinct abilities and expertise that can greatly aid in addressing the complexities of strategic competition, yet these assets are often overlooked or misunderstood. USSOF is too often seen as the direct-action, finishing force of the Global War on Terror era. Yet, the special operator of 2024 is not just the physically imposing “trigger puller,” but also the young man or woman who is an expert at coding. USSOF has a unique position that allows it to elevate the Joint Force’s capacity to navigate the entire spectrum of competition. Its activities prior to conflict, such as operational preparation of the environment (OPE), can shape the strategic environment with US competitors. This report contends that, when leveraged effectively, USSOF has the potential to play a pivotal role in promoting US global interests, particularly in addressing vulnerabilities across the competition continuum.

To fully harness USSOF’s role in strategic competition, the authors of this report propose recommendations to United States Special Operations Command (USSOCOM), Assistant Secretary of Defense for Special Operations and Low-Intensity Conflict (ASD(SO/LIC)), the Joint Force, the Department of Defense (DOD), and policymakers within the defense ecosystem. The recommendations are aimed at enhancing USSOF’s capabilities that already have utility in strategic competition, while shifting USSOF’s mindset toward this role. By implementing these measures, USSOF can better support the US interagency and promote US global interests in strategic competition. The recommendations are summarized below.

First, USSOF must adapt its mindset to play a larger role in strategic competition, expanding its non-kinetic activities and irregular-warfare concepts to counter the sophisticated capabilities of near-peer US adversaries like China and Russia. To do this, USSOF must balance its traditional tasks like countering violent extremist organizations (VEO) and weapons of mass destruction (WMD) operations, which will remain critical, with new challenges posed by strategic competitors. The latter necessitates the global synchronization of Joint Force planning to fully leverage USSOF’s capabilities across seven geographic combatant commands. Effective communication between ASD(SO/LIC) and USSOCOM is essential for articulating SOF’s strategic role across the DOD enterprise, but USSOF must be empowered by the Joint Force to proactively support competition below the threshold of conflict.

Second, USSOF’s capacity to synchronize the efforts of interagency partners, allied and partner militaries, and the Joint Force serves as a linchpin in addressing the complexities of strategic competition. There is nevertheless a gap in understanding regarding USSOF’s pre-conflict role among decision-makers. Many of USSOF’s activities can be leveraged more strategically to shape the competition environment, such as its aptitudes in special reconnaissance, foreign internal defense, civil-affairs operations, military information-support operations, unconventional warfare, security-force assistance, and foreign humanitarian assistance. By recognizing USSOF’s integral role in the competition continuum and integrating it more effectively into strategic planning, the DOD can leverage USSOF’s capabilities to their fullest extent, ensuring a proactive and comprehensive approach to strategic competition.

Third, USSOF can adapt its strengths to new challenges by enhancing capabilities in cyber, space, and undersea warfare, bolstering civil-affairs expertise for extreme environments like the Arctic, and investing in technological advancements like artificial intelligence (AI) to achieve cognitive overmatch in complex operating environments. Empowering USSOF to succeed in 2024 and beyond will require USSOF and the broader DOD enterprise to recognize that the special operator of the future includes a diverse cadre of cyber operators, culturally immersed experts, specialists in space, AI, engineering, or physics support operations, and gender-diverse teams.

Fourth, USSOF must find ways to measure its success in an unclassified setting by internally defining clear mission objectives for strategic competition and establishing tracking mechanisms to assess progress. Articulating success through deliberate campaigns to disrupt adversaries’ strategies can help communicate USSOF’s contributions and impact while safeguarding classified information.

Fifth, enhancing integration between USSOF and the US military services necessitates a better understanding of USSOF’s current capabilities and roles, improved communication, and synchronized global campaign planning to leverage USSOF’s strategic advantages effectively across multiple combatant commands and interagency partners. Clarifying USSOF’s presence and activities in regions pre-conflict, and facilitating collaboration between commands, can enhance intelligence sharing and support strategic-competition efforts.

Sixth, it is critical to leverage USSOF’s agility in identifying innovations from nontraditional defense-industrial partners. USSOF is a leader in identifying, testing, fielding, and evolving new, cutting-edge technologies that have utility across the Joint Force, DOD, and the Intelligence Community (IC). Enhancing USSOF and defense-industrial base relations involves improving collaboration between USSOF and leading-edge defense industries. Initiatives like SOFWERX and recommendations from the Atlantic Council’s Commission on Innovation Adoption can facilitate this collaboration, ensuring a culture of operational experimentation and incentivizing private-sector engagement to support USSOF’s mission success. Appropriately resourced, USSOF can continue to advance innovation adoption for the Joint Force at a time when doing so is essential for strategic competition.

Finally, USSOF must maintain effective cooperation with its allied counterparts while communicating its current and future plans, particularly regarding areas of focus, investments, and adaptations. The US interagency and DOD can learn from the experiences and models put forward by allies—such as the United Kingdom, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, and Norway—that have highly integrated special operations into their plans to compete with strategic challengers like Russia and China. In so doing, the United States should continue to recognize the importance of prioritizing special-forces capabilities, investing in small, specialized teams, and aligning with allies on shared priorities to facilitate multilateral operations.

These recommendations not only ensure USSOF’s relevance and effectiveness, but also reinforce its pivotal role in safeguarding US interests and promoting global stability. The US interagency and DOD should invest in USSOF’s many strengths for strategic competition. In so doing, USSOF will stand ready to navigate the complexities of the modern conflict and to serve as a formidable force in advancing US strategic objectives on the global stage.

Introduction

The United States and its allies and partners face an increasingly complex security environment in the twenty-first century, with competitors China and Russia leveraging all elements of their national power—diplomatic, information, military, and economic—to undermine US and allied security and prosperity. Considering strategic competition, the US Joint Force must adapt how it operates, recognizing that today’s security threats stretch well beyond the physical battlefield, and that competition and deterrence must be shaped prior to conflict. Both China and Russia view competition with the United States as taking place on a continuum, while the United States too often draws a bright line between peace and war while underinvesting in the competitive space between, leaving the United States at a disadvantage.

USSOF offers unique skills, competencies, capabilities, and experiences that can significantly support US goals and outcomes in strategic competition—but these tools are poorly understood. USSOF is often thought about through the lens of its past successes over the last two decades, notably in counterterrorism. But who special operators are today, where and how they operate, and the significant role they play in shaping the environment and creating successful outcomes for strategic competition remain underappreciated.

The 2018 and 2022 National Defense Strategies—and the integrated deterrence concept—acknowledge that today’s security threats will only be deterred through “employing every tool at the Department [of Defense]’s disposal.” USSOF is uniquely positioned to model, support, and enhance the Joint Force’s ability to do this. This report argues that, if harnessed correctly, USSOF can play a central role in advancing global US interests—especially across the seams and gaps of national power and artificial geographic boundaries that US adversaries exploit.

Some defense leaders are considering cuts to USSOF, which could dramatically alter its ability to contribute to strategic competition with China and leave an operational gap in current capabilities and future joint planning. How does USSOF support US and allied security imperatives, and how would a degradation of USSOF impact US competitive advantage in the 2020s and beyond?

This paper examines how the US government can best employ USSOF and apply its past successes and unique and joint operational approach to the challenges present in today’s era of strategic competition. The authors examine USSOF’s background and history, how USSOF enhances the US ability to outcompete China, and areas in which USSOF can be more effectively employed. The paper benefited from consultations with and peer review from many experts and practitioners across the national security community.

Background: What makes special operations forces “special”?

Special operators are ubiquitous across the US military services and combatant commands, yet their organization, operations, and missions are distinct from their counterparts across the Joint Force. USSOF comprises the active, guard, and reserve elements of each service component of the US Armed Forces that are designed, trained, and equipped to conduct and support special operations—“activities or actions requiring unique modes of employment, tactical techniques, equipment, and training often conducted in hostile, denied, or politically sensitive environments.” USSOF is unique from other parts of the military in its light footprint, specialized and inherently joint operations, and stealth approach. SOF typically deploys as tailored units based on an operation’s requirements, risk, and capabilities to sensitive regions of the world—often to places that conventional forces otherwise cannot access—and, in doing so, it can generate outsized strategic effects.

Globally positioned and readily deployed, USSOF provides decision-makers with low-visibility, small-footprint, and often low-cost options to secure US interests. It does this either by directly addressing threats or by indirectly engaging by, with, and through international allies and partners, thus allowing the United States to leverage partners’ capabilities and geographical familiarity and providing unique placement and access to partners that might be otherwise unavailable across the interagency. Accounting for just 3 percent of the US DOD’s budget, USSOF expands the response options available to the United States and its allies and partners, buying decision space for US and allied leaders. This is especially important in enabling US forces to shape the environment and conditions of competition well before conflict arises.

How are US Special Operations Forces organized today?

The ASD(SO/LIC) “oversees and advocates for Special Operations and Irregular Warfare throughout the Department of Defense to ensure these capabilities are resourced, ready, and properly employed in accordance with the National Defense Strategy.” USSOF is consolidated under the United States Special Operations Command, the unified combatant command headquartered at MacDill Air Force Base in Tampa, Florida. USSOCOM oversees the US Army Special Operations Command (USASOC), US Naval Special Warfare Command (WARCOM), US Air Force Special Operations Command (AFSOC), and US Marine Forces Special Operations Command (MARSOC). Within USSOCOM, the interoperability planning and equipment standardization of the various service SOF commands is overseen by the Joint Special Operations Commander (JSOC). To support the Geographic Combatant Commands (GCCs), SOCOM offers a sub-unified command per region aligned with the GCC in the form of Theater Special Operations Commands (TSOCs).

The five SOF truths

USSOF is guided by its Five Truths—key tenets that define both USSOF and special operators.

- Humans are more important than hardware.

- Quality is better than quantity.

- Special Operations Forces cannot be mass-produced.

- Competent Special Operations Forces cannot be created after emergencies occur.

- Most Special Operations require non-SOF assistance.

These truths echo the fact that a small number of SOF operators—carefully selected, well-trained, and exceptionally led—offer an unorthodox or specialized approach to security challenges that cannot be replicated at a larger scale across the conventional military force.

The special operator’s experience is distinctive—marked by high levels of adaptability, cultural understanding, and exceptional physical prowess that reflect years of specialized training, as well as global and joint experience that other servicemembers may not obtain. Special operations are joint in nature and involve liaising across the Joint Force and US government interagency organizations. As such, special operators gain unique exposure and understanding of how to execute joint operations with interagency partners during competition, and in preparation for crisis and conflict. Special operators are highly educated and uniquely trained for different environments and locales, and they possess the capability to employ unconventional thinking to achieve success.1Will Irwin and Isaiah Wilson, The Fourth Age of SOF: The Use and Utility of Special Operations Forces in a New Age (Macdill Air Force Base, FL: Joint Special Operations University Press, 2022). Furthermore, they are highly specialized, and their operational approach is characterized by cultural awareness, flexibility, and a tolerance for ambiguity, which allows them to function in complex and ever-changing conditions—a critical component when the presence of overt conventional forces may escalate tensions in any given region. These characteristics and capabilities mean that USSOF can be harnessed in creative ways to respond to strategic competitors whenever and wherever they are operating across the globe.

USSOF’s twelve core activities

USSOF is known for its role in US counterterrorism missions of the past two decades. Special operators played a central role in the twenty-year Global War on Terror (GWOT) via counterterrorism and counterinsurgency missions. However, USSOF executes twelve core activities (both before and during conflicts or crises) that are lesser known and crucial to strategic competition. These activities often overlap and rarely take place in isolation. Many of these activities are highly relevant to combatting China’s and Russia’s malign activity or altering their decision calculus and popular perceptions across the globe.

- Direct Action: Executing short-duration strikes and small-scale offensive actions to seize, destroy, capture, exploit, recover, or damage designated targets.

- Special Reconnaissance: Actions conducted in sensitive environments to collect or verify information of strategic or operational significance.

- Unconventional Warfare: Executing actions to enable a resistance movement or insurgency that is aiming to coerce, disrupt, or overthrow a government or occupying power.

- Foreign Internal Defense (FID): Activities geared toward supporting the host nation’s internal defense and development, including safeguarding against subversion, terrorism, insurgency, or other threats to stability and internal security.

- Civil Affairs Operations (CAO): Enhancing the relationship between US and allied and partner military forces and civilian authorities in areas where military forces are present.

- Counterterrorism (CT): Actions taken directly against terrorist networks, as well as actions to influence or render global and regional environments inhospitable to terrorist networks.

- Military Information Support Operations (MISO): Planned activities aimed at conveying specific, pre-selected information to foreign audiences. Such information is often aimed at influencing the emotions, motives, objective reasoning, or behavior of foreign audiences, groups, individuals, or sometimes governments in a manner favorable to US or host-nation objectives.

- Counter-proliferation of WMD: Activities to support US government efforts to curtain the development, possession, proliferation, and use of chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) weapons by governments and non-state actors.

- Security Force Assistance: Organizing, training, equipping, rebuilding, or advising various components of foreign security forces.

- Counterinsurgency (COIN): The amalgamation of civilian and military efforts designed to end insurgent violence and facilitate a return to peaceful political processes.

- Hostage Rescue and Recovery: Offensive measures taken to prevent, deter, preempt, and respond to hostage incidents, which may include the recapture of US facilities, installations, sensitive materials, or personnel in areas hostile to the United States.

- Foreign Humanitarian Assistance: A range of Department of Defense humanitarian activities conducted outside the United States and its territories, and alongside other humanitarian entities, to relieve and reduce human suffering.

These twelve activities form a robust, interconnected, and mutually supportive framework that allows USSOF to navigate different phases of competition and conflict across the competition continuum. Rarely does a special operation occur without involving or impacting one or more core activities. For instance, an unconventional-warfare campaign might seamlessly incorporate direct action and special reconnaissance elements, highlighting the fluidity and adaptability inherent in special operations. Some special operations are carried out by USSOF’s cross-functional teams (CFTs), which combine the unique capabilities of Civil Affairs, psychological operations (PSYOP) forces, special forces, and enablers. USSOF was the first to execute and operate multi-domain command and control, and helped define what is now doctrine in multi-domain operations.

Special operations are multifaceted by design, and each service may bring distinctive skills and missions.2In some cases, the distinct differences between the mission sets of each service are classified, but certain obvious differences are plain. Each service conducts foreign internal-defense operations. For example, AFSOC may work with foreign airmen to assess and improve foreign aviation capabilities, while WARSOC may support foreign forces on harbor clearance, search and recovery, and critical maritime infrastructure. For more information, see: “Joint Publication 3-22: Foreign Internal Defense.” Employing different specialties and tools, USSOF takes a holistic approach to threats across the competition continuum. Such an approach is critical to compete with US strategic rivals that operate in spaces beyond the military domain, including the information, diplomatic, economic, and legal realms. As such, USSOF has, and can continue to have, a tremendously valuable role in strategic competition.

USSOF’s role prior to and during conflict

Special operators are adept at shaping outcomes in response to evolving challenges, performing their core activities years before conflict breaks out and remaining on the ground in the aftermath of a crisis. For example, during pre-conflict phases, USSOF’s reconnaissance missions can provide information to the IC in key regions. USSOF can operate behind enemy lines and sometimes have access to sources and information that members of the IC do not, contributing vast amounts of intelligence to the United States.

Meanwhile, USSOF’s security cooperation programs are dedicated to enhancing partner capability and capacity while increasing US regional access and influence. Key aspects of this relationship include fostering partner resilience against subversion and coercion—and, when necessary, resistance to occupation. A prime example of this is the significant role that USSOF played in helping Ukraine build and train a professional and capable military force after the illegal Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014. At that time, Ukrainian military forces lacked command and control and were not well-trained in operating key capabilities. Following 2014, US, United Kingdom (UK), and other allied SOF trained the Ukrainian military, supporting its evolution into the professional and capable military force we see today, which has been much better positioned to respond to and tenaciously fight Russia’s ongoing war against Ukraine.

USSOF provides a critical leg of integrated deterrence, alongside conventional and nuclear military capabilities, by executing irregular aspects of competition that remain below the threshold of armed conflict. This includes undertaking specialized reconnaissance, irregular warfare, medical support, clandestine logistics, data collection, and human intelligence (HUMINT) analysis—or military information-support operations, known as MISO—against potential adversaries before a conflict arises. SOF also bolsters deterrence by denial and punishment, demonstrating to allies and partners how to stand up to coercion from Russia, China, and other adversaries.

In the event of a crisis, USSOF is strategically positioned at the forefront, offering support across the Joint Force and US government interagency organizations in critical areas. For example, USSOF supports the development of US Embassy Emergency Action Plans, provides humanitarian assistance, and generates intelligence to establish conditions for large-scale combat operations. In essence, USSOF’s role is proactive. Instead of waiting for the onset of conflict, special operators are engaged in a region for an extended period before such a conflict ever emerges, and they set the environment for future engagement and interoperability with other military forces.

History of USSOF: SOF’s evolving purpose and how its history lends to competition today

The creation of USSOF and its role in the twentieth century

The inception of USSOF dates back to 1942. Born out of necessity during the Second World War (WWII), the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, establishing air, ground, and maritime SOF to meet the particular needs of warfighting theaters. These OSS forces, led by Bill Donovan, became critical to the global operations of the Allied forces in World War II, acting as elite raiding forces in Europe, enablers of Nazi- and fascist-resistance movements in the Mediterranean and Middle East, and the executors of an unconventional-warfare campaign in China and East Asia. The OSS forces were dissolved by President Harry Truman following the end of WWII, and all the special intelligence and warfare functions were then transferred to the War Department. By the time the Korean War began in 1953, there were no remaining official standing special-operations units, but their noticeable absence resulted in an accelerated effort to rebuild such capabilities during that decade.

During the Cold War, the Department of Defense recognized the value of irregular warfare to enable resistance groups in Warsaw Pact countries. This led to the 1952 establishment of the Army’s Psychological Warfare Center at Fort Bragg—later renamed the Special Warfare Center. As their capability was rebuilt, USSOF forces deployed troops throughout the Cold War, supporting covert Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) operations in Tibet, Iran, Eastern Europe, and Cuba; supporting and training south Vietnamese troops; and evacuating missionaries and other personnel from unstable regions of the Congo, among other missions.

The true value of USSOF during the Cold War was realized when President John F. Kennedy stressed the need for the armed services to invest more heavily in guerrilla and counter-guerrilla operations as an effort to combat Soviet influence operations worldwide. As it expanded to create new units and training centers across the services, USSOF emerged as “pioneers in interagency cooperation,” collaborating with entities such as the CIA by conducting long-range reconnaissance missions and medical support missions to Vietnam.3Irwin and Wilson, The Fourth Age of SOF. During this time, special operations became one of the US military’s key enablers to counter coercion below the threshold of armed conflict.

In the aftermath of Vietnam, USSOF’s capabilities—like those of other services and commands—were reduced because of budget cuts and downsizing. The failed Iranian rescue mission of 1980, known as Operation Eagle Claw, led to a flurry of reorganization efforts in Congress, culminating in the permanent establishment of USSOCOM in 1987 and the creation of an office devoted to special operations and low-intensity conflict (SO/LIC) within the Office of the Secretary of Defense, all of which resulted in the current organization of USSOF.

USSOF in the GWOT and the twenty-first century

USSOF is perhaps best known for its work throughout the GWOT. USSOF carried out a diverse range of missions worldwide, serving as the primary tool in the US fight to counter VEOs. Beyond engaging in combat operations in Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, and the Philippines, USSOF played a crucial role in executing theater campaign plans and implementing national strategy on a global scale.

During this time, USSOF doubled in force size and more than tripled in budget to meet the growing threat environment; during some periods, its presence overseas more than quadrupled. SOF was vital in building partner capacity, providing low-cost, low-footprint options to understand and impose costs on malign adversary activity and expand US influence and access with key partners and allies. Importantly, USSOF established linkages to conceive and implement a true Joint Interagency Intergovernmental Multinational (JIIM) strategy in multiple locations—especially in areas in which the Department of Defense could not be the lead active player, such as in Africa. The value of SOF’s authorities and culture of moving quickly against a problem was clearly demonstrated during GWOT. This entailed applying resources and focus against a challenge, but it also meant the research and development (R&D), experimentation, fielding, and application of novel—and potentially game-changing technology—tactics, techniques, and procedures.

While USSOF conducted a diverse range of operations during this time, the bulk of US public and policymaker attention was focused on the direct-action campaigns—such as the one that killed Osama Bin Laden, Operation Neptune Spear—that made USSOF better known. In some ways, USSOF suffers from its own success. USSOF faces the challenge of its media-molded image versus the reality of it being a highly expert and quiet force. As such, some still perceive USSOF’s role as confined to direct action despite the range of indirect action and other operations it conducts, ranging from training and equipping components of foreign security forces to enhancing relationships between US forces and foreign civilian authorities.

Public perceptions of USSOF

Perhaps due to its success in the GWOT, USSOF is too often viewed only as the finish force, closing the kill chain for its conventional service counterparts.4Because of its reputation for direct action, some policymakers interviewed for this project described USSOF as being seen as the “finish force.” This concept refers to the idea that, during a conflict, USSOF can step in and conduct operations that its conventional service counterparts cannot—but this flexibility should not just be seen as adaptability on the battlefield. Instead, modern special operators should be understood as playing a role much earlier in the management of competition, prior to conflict. USSOF operates globally, across the entire competition continuum, and rapidly tests and employs novel or critical capabilities to enhance security operations.5The competition continuum describes a world neither at peace nor at war, but instead a world of “enduring competition conducted through a mixture of cooperation, competition below armed conflict, and armed conflict.” For more information, see: Department of Defense, “Joint Doctrine Note 1-19, Competition Continuum.” USSOF will continue to conduct CT and COIN operations, when necessary, but today’s security environment requires USSOF to prioritize its role in strategic competition—this may more closely mirror the role it played below active armed conflict in the Cold War era.6See section above about USSOF’s history and role during the Cold War.

USSOF has continued to play this role in some capacity over the past twenty years, albeit less visibly than some of its actions during the GWOT. Furthermore, if called upon, USSOF has the competencies and authorities to employ irregular-warfare concepts and gray-zone tactics in strategic competition. Nevertheless, few decision-makers think of it that way. It is time that policymakers update their understanding of USSOF and enhance the valuable role it can play in strategic competition.

USSOF today in the context of strategic competition

USSOF’s strengths applied to strategic competition

Today, the US Joint Force confronts a pacing threat in China and an acute threat in Russia—far more sophisticated adversaries than it faced in VEOs throughout the GWOT.7“2022 National Defense Strategy.” Prevailing in this era of strategic competition requires the Joint Force to shift its competitive mindset in order to effectively respond to threats spanning the competition continuum and cutting across theaters and domains. Within this three-dimensional approach to competition, USSOF is a critical operator, complementing conventional-force readiness and military dominance with a unique blend of competencies and capabilities that can be leveraged to deter, prepare for, and respond to armed conflict.

The 2023 Joint Concept for Competing defines strategic competition as “a persistent and long-term struggle that occurs between two or more adversaries seeking to pursue incompatible interests without necessarily engaging in armed conflict with each other.”8“Joint Concept for Competing.” In addition, the concept of the “competition continuum” was introduced as a Joint Concept in 2019, and describes a world of enduring competition conducted through a mixture of cooperation, competition below armed conflict, and armed conflict—a description that allows for simultaneous interaction with the same actor across different situations.9Ibid.; “Joint Doctrine Note 1-19, Competition Continuum.” These two concepts acknowledge that US adversaries have circumvented US conventional military dominance by competing below the threshold of armed conflict for some time. Following Operation Desert Storm in 1991, the United States celebrated a decisive battlefield win, while US competitors learned they must devise ways to compensate for unrivaled US conventional power and win without fighting through non-conventional means. USSOF is accustomed to operating across the competition continuum and cooperating with allies and partners to support US objectives, while simultaneously creating dilemmas for adversaries in an evolving threat environment. These factors make USSOF a versatile and critical instrument in strategic competition not only in the military domain, but also operating in support of diplomatic and economic objectives.

The following section outlines four key competencies USSOF brings to bear to support US strategic competition: its engagement with allies and partners, its global footprint, its ability to achieve effects across the competition continuum, and its cutting-edge use of technology.

I. Global and persistent engagement with allies and partners

The first major competency of USSOF is its proactive and sustained engagement of allies and adversaries globally.

USSOF is global by nature, confronting adversaries across every domain and every part of the world where China and Russia are undermining US and allied interests. Beijing leverages its influence, military, and predatory economic practices to bully its neighbors and project power far beyond the Indo-Pacific. Russia simultaneously wages a war of aggression against Ukraine, challenges national sovereignty across Europe, and undermines the security of nations globally through its cyberattacks, intimidation, and information operations. USSOF’s global role enables it to respond to China and Russia internationally.

USSOF builds and maintains authentic and multigenerational connections with allies and partners by training, advising, and assisting various countries in their security. This global presence and these relationships also enable USSOF to observe and counter Chinese and Russian influence in key regions while simultaneously engaging with and building trust with key partners. US partners may have greater access to observe Chinese or Russian activity. As such, USSOF engagement internationally not only supports partners but also creates greater options for the United States to counter adversarial influence.

USSOF approaches its relationships with allies and partners through persistent (rather than episodic) engagement, which generates a comprehensive understanding of host nations, threats to their security, and the second- and third-order effects of decisions and operations in those local contexts. USSOF’s enduring partnerships allow the United States to engage with nations in areas of strategic competition by assisting them with the problems they care about most. This is especially important for certain partners that may not view China or Russia as a threat, leaving USSOF as one of the only viable and trusted partners to discreetly engage on US foreign policy matters in certain areas.

USSOF spearheaded the by, with, and through approach for the US military, in which “operations are led by [US] partners, state or nonstate, with enabling support from the United States or US-led coalitions, and through US authorities and partner agreements.” USSOF’s approach centers allies and partners in the defense of their own nations, often leading to more successful results. This approach is better for the partner nation and also for the United States.

USSOCOM also has a USSOF Civil Affairs element, which works “by, with, and through unified action partners to shape conditions and influence indigenous populations and institutions” in support of DOD and US embassy strategies.10Under the DOD “Directive 2000.13, Civil Affairs,” USSOCOM developed “Directive 525-38, Civil Military Engagement.” In this capacity, USSOF supports other parts of allied governments to leverage non-military instruments of power. In so doing, USSOF is able to gain “placement and access”—proximity to or the ability to approach an individual, facility, or information that enables one to carry out an intended mission—in geographic areas where US embassies otherwise do not have a presence. This expands the options available to US decision-makers to respond to activities by China and Russia in areas where the United States may not have much of a diplomatic or conventional military presence.

While physical presence remains important, USSOF can also support nations from a distance or virtually, which helps reduce costs and provides operators with greater flexibility by avoiding direct confrontation or escalation that may come from physical presence. Throughout the war in Ukraine, USSOF has advised and assisted Kyiv from a distance. Following the 2014 invasion, the US military brought together conventional and special-operations troops to create the Joint Multinational Training Group-Ukraine, including a “Q course.” This Army Special Forces qualification course (formally called the Special Forces Qualification Course) teaches everything from combat competencies and survival, evasion, resistance, and escape (SERE) to how to navigate in an unconventional-warfare environment. Even without a large physical footprint in Ukraine, USSOF has been able to effectively assist Ukrainians with training and logistics.11Atlamazoglou, “US Special Operators Borrowed a Unique Part of Army Green Beret Training to Prepare Ukrainians to Fight Russia.” This demonstrates a valuable competency, and can serve as a model for training and supporting other countries relevant to strategic competition that may otherwise be difficult to physically operate within.

USSOF’s relationships can be multigenerational. By operating in the same regions for decades, USSOF builds relationships that can breed mutual trust and understanding. These relationships (and the inherent trust with allies and partners that follows) are sustained through USSOF and allied counterparts participating in joint training exercises, attending each other’s training courses, and sharing tactical and strategic experience. Through such exchanges and training, US allies and partners enhance their warfighting capabilities and improve their interoperability with the United States. In turn, the United States gains a deeper understanding of the security cultures and threat perceptions of other countries. This information improves US activities and operations, and further guides decision-making by opening avenues for the United States to engage new stakeholders abroad. US engagement with regional stakeholders can complicate an adversary’s risk calculus, as it is forced to consider the potential consequences of aggression against regional actors to which the United States is tied.

USSOF’s tailored approach to its regional relationships generally produces special operators with more global and joint experience earlier in their careers when compared to their service counterparts. Through their deployments, special operators exchange tactics, techniques, and procedures with partner nations. Their cultural adeptness and multi-domain backgrounds empower USSOF to plug in quickly, adjust to varying cultural, geographic, and political contexts, and build new connections for the Joint Force for years to come.

II. Gaining placement and access across the globe

Secondly, USSOF’s deep alliances and partnerships offer an asymmetric advantage over China, Russia, and other competitors. USSOF collaborates with allies and partners to create global impact in a way that may be outsized to its presence. Even a small USSOF unit can take localized actions that might compel adversaries to contend with widespread repercussions. For example, USSOF may work with an Indo-Pacific nation to gain increased access for the United States Air Force to operate in the region, signaling to China increased US capacity and maneuverability that could alter China’s risk calculus as it conducts maritime activities in the Indo-Pacific. Or USSOF may work with an African partner to counter Chinese or Russian local information operations that adversely affect its influence in multiple countries across the region and beyond.

USSOF’s partnerships and presence in host nations build US regional placement and access, in turn providing virtual and/or physical proximity to an entity of interest. This placement and access support the Intelligence Community by providing insights in normally inaccessible locations while also enhancing the Joint Force’s ability to compete across the globe’s farthest corners, enabling it to support allies and partners in identifying and responding to adversarial and illicit behavior. For USSOF, in particular, this proximity forms the foundation for responding to coercive or subversive activity below the threshold of armed conflict. For example, China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) gives it placement and access in a range of countries across the Indo-Pacific, Africa, Europe, and Latin America. Through subversive economic practices, China has capitalized on key industries, accessed new markets, and coercively influenced local decisions in developing countries by leveraging its economic power. This all-of-nation approach buys China influence and could enable an expanded military presence—for instance, through the acquisition of ports and waterways that serve as potential maritime chokepoints. China’s BRI activities have taken place in some countries where the United States lacks a large presence or access, but USSOF can and does operate in areas where other US entities do not.

If harnessed effectively, USSOF can be leveraged in key strategic regions to educate local governments, conduct reconnaissance of local activity, employ information operations, collect intelligence, and collaborate with interagency partners. As such, USSOF can be used to mitigate or respond to Chinese and Russian attempts to expand their influence in regions that are lesser priorities for US conventional force presence. USSOF’s global access is particularly important when crises or conflicts erupt. For instance, as the Israel-Hamas conflict continues, USSOF could surge on its CT, COIN, and hostage-rescue mission sets in the Middle East, allowing the Joint Force at large to remain focused on the pacing challenge of China. Overall, USSOF global presence enables the United States to maintain strategic ground in other, less-prioritized regions, while preserving a relatively light and inexpensive footprint.

The light and relatively affordable nature of USSOF’s global presence furthers US interests in parts of the globe where the United States may not have a strong foothold, providing outsized value.

III. Operations across the competition continuum

USSOF is adept and experienced in operating below the threshold of conflict. This “gray zone” of competition can be defined as “the space in which defensive and offensive activity occurs above the level of cooperation and below the threshold of armed conflict.” Dating back to the Cold War era, special operations were one of the few military capabilities that challenged coercion below the threshold of armed conflict. This space and time prior to armed conflict is increasingly central in modern competition, especially when adversaries employ a “win without fighting” strategy. China and Russia rely on cyber, economic, information, and other asymmetric capabilities to advance their interests, especially when they cannot outmatch US conventional military superiority or when unconventional activities achieve their objectives just as well.

The United States has recognized the need to operate more strategically along this competition continuum in order to better compete with China and Russia. The 2022 National Defense Strategy recognized the need to “campaign across domains and the spectrum of conflict” to improve the US understanding of its operating environment and to shape the perceptions and risk calculi of US adversaries.12“2022 National Defense Strategy,” 8–11. Through the United States’ own gray-zone activities—such as the development of partner nations’ resistance and resilience capabilities, and information and cognitive operations—USSOF can help mitigate strategic risk, support US national objectives, and buy “decision space” for US and allied leaders, while limiting exposure to political and economic risks that may come from a larger military presence or more overt action.13Individuals interviewed for this study highlighted USSOF’s ability to “buy decision space” for the United States. This is possible because USSOF is able to discreetly build placement and access in regions otherwise denied or difficult for the United States to access. By doing this, USSOF gains a holistic intelligence picture, intricate relationships, and a local understanding of actors and areas that the US government may not otherwise have, thereby expanding the range of policy options available to US and allied decision-makers.

“Integrated deterrence” campaigning should rely upon USSOF activities, including (but not limited to) its ability to establish resistance mechanisms, conduct information operations, engage in Civil Affairs, and collect intelligence. Such activities impact adversaries by tying up or forcing them to reposition their resources, thus creating disruptions and dilemmas that benefit the United States.14A planned resistance mechanism is the well-organized resistance capability prior to a potential invasion and subsequent occupation for US allies and partners. Establishing such mechanisms prior to an invasion that could lead to a loss of territorial integrity or sovereignty provides the United States and its allies and partners a blueprint for national resilience in a pre-crisis setting, while formulating resistance requirements and facilitating planning and operations in the event of an adversary compromising or violating the sovereignty and independence of allied or partner nations. USSOF’s role in executing integrated deterrence is perhaps best articulated through its irregular-warfare capabilities, which offer a “critical tool to campaign across the spectrum of conflict, enhance interoperability and access, and disrupt competitor warfighting advantages while reinforcing our own.” USSOF deters adversaries’ actions across the continuum by illuminating and confronting acts of proxy aggression, information warfare, economic warfare, and subversion. This enhances the options available to US decision-makers while simultaneously sowing chaos that disrupts adversarial decision-making.

USSOF’s competencies across the competition continuum are as follows.

Information Warfare

USSOF actively engages in the information domain by exposing and countering adversary propaganda and disinformation, as well as campaigning—that is, conducting “logically linked military initiatives”—to achieve US defense priorities over time.15“2022 National Defense Strategy,” 1. In 2019, then commander of US Special Operations Command General Richard Clarke stated that 60 percent of the special-operations community’s focus was “working in the information space,” as opposed to a 90-percent focus on “the kinetic fight” just a decade earlier. USSOF’s MISO activities have more than tripled in the past three years, with special operations contributing 60 percent of MISO activities conducted worldwide in fiscal year 2022. This trend will likely intensify in future conflict as the information domain remains a key arena for strategic competition, as China and Russia use information or “informatized” warfare to counter US strategic objectives and further their own.16Maier and Fenton, “Statement for the Record.” Information operations can be used to great effect. For example, Ukraine has successfully leveraged information operations to rally support for its armed forces and—tactically and operationally—to “[erode] the will of individual [Russian] soldiers,” which has partially contributed to seventeen thousand Russians deserting the military.

Recognizing the prominence of information and cognitive warfare, USSOCOM established the Information Warfare Center (IWC) in 2021. The IWC aims to enhance and consolidate USSOCOM’s psychological-operations capabilities, in conjunction with information-related capabilities in the cyber and space domains, specializing in “influence artillery rounds”—detecting adversarial activity across the globe and pushing that information to operators, who then must identify tailored informational “munitions” to match the target confronting them.

Space and cyber warfare

USSOF similarly recognizes the significance of the cyber and space domains, with the US Army spearheading the concept of a “modern triad” consisting of space, cyber, and special operations to “provide options to commanders to deter activity below the threshold of conflict.” While cyber, space, and special-operations capabilities are powerful on their own, melded together they generate vast options and opportunities for the Joint Force to rapidly influence outcomes across the competition continuum.

The triad might manifest as follows.

- Special Operations Command “provides unique access at the tip of the spear for both space enabling infrastructure and cyber access”;

- Space and Missile Defense Command “provides missile defeat and other unique space capabilities”; and

- Cyber Command “provides cyber capabilities as well as data analytics to better inform operations of the other two legs.”

For example, USSOF could use its unique placement and access to enable a US Cyber Command (USCYBERCOM) operation into a remote adversary downlink site, holding its ability to conduct space domain awareness at risk and giving USSPACECOM an option during crisis or conflict. This triad, which combines intelligence threads and capabilities, offers commensurate responses to low-intensity and hybrid threats.

Cyber, space, and special operations are distinct from other military instruments in their multi-domain “global reach.” Each of these tools is not confined to operations in a traditional domain or geographic theater; rather, their application extends across all the military services and combatant commands.17Maier and Fenton, “Statement for the Record.” USSOF’s ability to effectively employ the triad, in turn, will integrate this response option into Joint Force campaigning and contingency response plans to fill operational gaps across domains and regions. Still today, this idea remains largely conceptual at the joint level—the space component is less natural to bring in, given USSOF has long utilized cyber and signals intelligence capabilities to track targets.

Supporting the Joint Force and interagency

The primary objectives of operating in the gray zone are to counter malign actions below the threshold of armed conflict and to ensure competition does not escalate into full-blown conflict. Should conflict break out, however, USSOF’s OPE activities will prove critical for supporting large-scale combat operations. During combat, USSOF is equally critical as an enabler for the Joint Force. USSOF is well-positioned to provide a firsthand assessment of the situation and response options given its persistent presence and engagement in key regions. For example, USSOF could play a pivotal role in capturing key terrain and securing ground lines of communication—both actions that would set the conditions for Joint Force success while disrupting adversarial military planning. During conflict, USSOF can help mitigate strategic risk for the Joint Force through supporting operations. This was demonstrated during Operation Inherent Resolve, during which small numbers of special operators, in concert with regional partners, took back territory held by the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS), constrained Iranian aggression, pushed back against Russian encroachment, and limited escalation between Kurdish and Turkish forces.

Furthermore, USSOF teams can serve as a focal point for synchronizing the effects of interagency partners, allied and partner militaries, and the Joint Force. This collaborative approach is evident in the fifth “SOF Truth,” which states that “most special operations require non-SOF assistance.”18“SOF Truths.” USSOF’s effectiveness is enhanced by its integration with other DOD components and interagency partners, merging military expertise with diplomatic, economic, and informational tools. At the same time, USSOF augments joint and interagency operations, thus enabling a comprehensive approach to address strategic competition by aligning diverse capabilities toward common objectives. Decision-makers across the interagency and in the DOD may not appreciate the full role USSOF plays prior to conflict. Not only is it impossible to build USSOF capabilities overnight in the event of a conflict, but also, if USSOF capabilities are employed only at the onset of a conflict, they will not have been employed to their full effect.

With the proper authorities, special operations can extend the scope, scale, and reach of interagency deterrent tools by both providing US government partners with the inputs required to execute operations (e.g., placement and access) and amplifying the desired output or effect (e.g., bringing together various instruments of power). This is particularly important given that USSOF has formal operational-planning experience that is not inherently a function of other government departments and agencies. For example, USSOF works with the Department of Treasury’s Office of Foreign Asset Controls to enhance sanctions support capability on the ground; it leverages MISO and Civil Affairs to amplify Department of State public diplomacy; and it convenes various stakeholders for cross-cutting human security issues such as illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing, and mitigating harm to civilians. JIIM partnerships are required to compete against China and Russia, and USSOF is well-positioned to support and enable them.

USSOF includes specialized teams that can bolster US security advantages below the threshold of conflict. While much of USSOF’s activity falls within the classified realm, USSOF’s cross-functional teams execute numerous SOF operations. Building upon the definitions of USSOF’s core activities provided above, this holistic approach addresses threats across the competition continuum in the following ways.

- Civil Affairs forces “conduct preparation of the environment, support to unconventional warfare, foreign internal defense, and civil network development and engagement across the competition continuum”;

- Psychological Operations forces “conduct Military Information Support Operations (MISO) in permissive, uncertain, and hostile environments to change the behavior of foreign audiences—both friendly and adversarial—in support of US objectives”; and

- Special Forces “discretely shapes the operating environment in both peace and complex uncertainty,” with two primary missions of unconventional warfare and foreign internal defense.19“A Vision for 2021 and Beyond.”

These three elements comprise a comprehensive intelligence picture and can support the Joint Force’s creation and execution of plans to counter Chinese, Russian, and other adversaries’ gray-zone activities in key regions.

IV. At the cutting edge of capability development and employment

USSOF is creative about harnessing and experimenting with emerging technology and capabilities. USSOCOM “continues to serve as a pathfinder” for integrating data-driven technologies, such as artificial intelligence and machine learning, into the Joint Force by serving as early adopters of new technology.20Maier and Fenton, “Statement for the Record.” USSOF have a proven track record of engaging with the US defense-industrial base and testing novel capabilities in combat effectively. Such experimentation is valuable as emerging technology enables the Joint Force to compete with an increasingly technologically advanced China. USSOF is adept at proactively identifying promising early technology from the private sector and reaching out to companies to adapt technology to suit the forces’ needs.

Due to USSOF’s smaller size, proactivity, and service-like acquisition authorities, it is often able to acquire technology more rapidly than other parts of the DOD. USSOF’s external innovation unit, SOFWERX, collaborates with various nontraditional participants in the defense innovation ecosystem through events and Small Business Innovation Research programs (SBIRs), rapidly enhancing the equipment and capabilities of special operators.21“Industry,” SOFWERX, last visited February 17, 2024, https://sofwerx.org/industry. SOFWERX, in turn, became the beta model and launch point for all the subsequent “WERX” across the services, such as AFWERX, SPACEWERX, etc. From transmitting and seeing in dark tunnels to flying unmanned aerial vehicles in denied airspace, USSOF often serves as a technological testbed for capabilities that have utility across the Joint Force and, in many cases, advances capabilities to ensure battlefield superiority. USSOF is a leader in identifying, testing, fielding, and evolving new, cutting-edge technologies across the Department of Defense and the IC. Appropriately resourced, USSOF can continue to advance innovation adoption for the Joint Force at a time when doing so is essential for strategic competition.

USSOF is a particularly impressive model for innovation because it can “turn the crank of force design, force development, and force employment faster than any other part of DoD,” which “lend[s] it an inherent advantage in generating innovative capabilities.” Able to rapidly develop, test, and implement emerging technologies at earlier points of relevance, USSOF tends to live at the cutting edge of defense innovation. For example, the Global Positioning System (GPS) was largely untested in combat until Operation Desert Storm, during which special operations forces used GPS to conduct special reconnaissance deep in enemy territory. USSOF informed GPS techniques and equipment for the entire Joint Force. This form of combat testing can help the larger military identify, transition, and adopt promising technologies for future conflicts.

What’s next? Enhancing USSOF in the 2020s and beyond

This report has established the invaluable role that USSOF can and does play in enabling the United States to achieve its strategic objectives, including adapting to and outpacing China, the pacing threat. USSOF should be harnessed more effectively by the US policymaking community and the DOD to help achieve US strategic-competition goals. USSOF is uniquely able to operate in early phases of the competition continuum (prior to conflict) and in austere locations, while using specialized tools and methods that the rest of the Joint Force cannot. Specifically, USSOF can help realize US deterrence goals without the need for escalation to conflict, and can provide the Joint Force with preconditioned advantages if crisis erupts.

Looking forward, as the whole Joint Force adapts to meet an era of strategic competition, USSOF must also continue to evolve. USSOF should consider the following recommendations to ensure it can best support US goals in strategic competition.

Revamping USSOF’s mindset for strategic competition

First, USSOF must continue to adapt its competitive mindset to play a larger role in strategic competition. In addition to the important role it plays in direct action, USSOF should expand its disruptive non-kinetic activities and irregular-warfare concepts with the goal of chipping away at US adversaries’ diplomatic, economic, and military strength. Those who weave USSOF capabilities into regional and global campaign plans should consider the significant utility of SOF’s indirect action. China and Russia pose vastly different challenges from VEOs, with which USSOF became well-acquainted over the past two decades. Near-peer competitors deploy sophisticated military, intelligence, diplomatic, and economic capabilities to secure their interests, and strategic competition thus creates a threat environment that is quantitatively and qualitatively distinct from the GWOT. Direct action—such as countering VEOs—will continue to be a task for USSOF, enabling the rest of the DOD to focus on other strategic priorities. However, as USSOF recommends to decision-makers how best to harness its capabilities, it should emphasize its in-depth understanding of complex problems, rather than a predisposition for immediate action.

Second, it is important that USSOF—and the Joint Force at large—recognize that the US military should most often play a “supporting,” rather than “supported,” role in conducting foreign affairs, in support of the State Department as lead.22In this sense, the DOD will support and enable other interagency partners, like the Department of State, in achieving their goals across the spectrum of competition, rather than remaining in pole position as the lead entity of an operation. See: Cartwright, et al., Operationalizing Integrated Deterrence. This necessitates flexibility and adaptability, which USSOF showcases with its ability to quickly plug into new contexts and work with interagency counterparts and country teams. However, even then, much of today’s existing USSOF-interagency cooperation is built around the GWOT era, during which non-military instruments of power primarily supported USSOF-led operations (rather than the other way around) and partnerships were based largely around information sharing. USSOF’s role as a supporting entity will be most evident below the threshold of conflict, where non-DOD levers of power are often better suited than the military arsenal. USSOF must be empowered to play a supporting role by policymakers, who should see USSOF as playing a proactive—rather than reactive—role in the management of competition, employed preemptively to avoid escalation, rather than as a last resort when nothing else works.

Third, this shift in USSOF’s role must be similarly reflected in its alliances and partnerships. While USSOF fosters partner-nation resilience against Russia and China through foreign internal defense (FID), there is more it could do. For example, USSOF could expand its support for implementing the Global Fragility Act with focus countries, applying those principles in partnership with Taiwan and European nations to further develop their reserve force capabilities and whole-of-society resilience, both of which would be crucial to inhibit China from taking over Taiwan or respond to a potential Russian invasion. Policymakers should consider revising legislation such as the foreign security force capacity-building authority in Section 333 to support USSOF’s evolving role in strategic competition and stabilization activities.

Finally, as USSOF evolves its actions and attitudes toward strategic competition, it will face hurdles in overcoming orthodox DOD culture, bureaucratic morass, budget constraints, and recruitment and retention issues, including as other services request billets back. The office of ASD(SO/LIC) offers an important voice for USSOF in Washington, DC, to help USSOCOM navigate and advocate for its mission requirements within the Pentagon and wider interagency.

“Walk and chew gum at the same time”

Operating in an era of strategic competition does not mean that threats prioritized during GWOT have disappeared—USSOF must be able to manage its more traditional tasks and its coordinating authority for countering VEO and WMD operations while executing its new ones.23It should be noted that China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea all use proxy elements to achieve their objectives, some of which may include terrorist organizations or other nefarious elements that USSOF is equipped to address.

USSOF partially does this through its activities across seven geographic combatant commands; thus, globally synchronizing Joint Force planning is key to fully recognizing and enabling the value of special operations. USSOF can compete with both China and Russia in traditional and less-traditional theaters. For example, USSOF’s pre-conflict capabilities can and should be employed more extensively in China’s near abroad—the Indo-Pacific—through maritime and undersea operations, sensitive activities, and partnership building. At the same time, USSOF can play a central role by competing with China and Russia in their far-abroads, particularly in US Southern Command and US Africa Command, while other parts of the Joint Force are focused elsewhere. Both of these combatant commands are “deeply immersed in peer-competition with China” in ways that have direct implications for the United States’ overall security posture. For example, China’s base in Djibouti allows it to project power further abroad than it would otherwise be able, and China’s space ground station in Argentina enables it to monitor US space assets. In these two regions, USSOF could leverage its OPE, special reconnaissance, intelligence capabilities, and partnerships to gain competitive advantages over near-peer adversaries. Altogether, USSOF’s global footprint enables the Joint Force to target and track near-peer adversaries globally and coordinate approaches to them regionally.

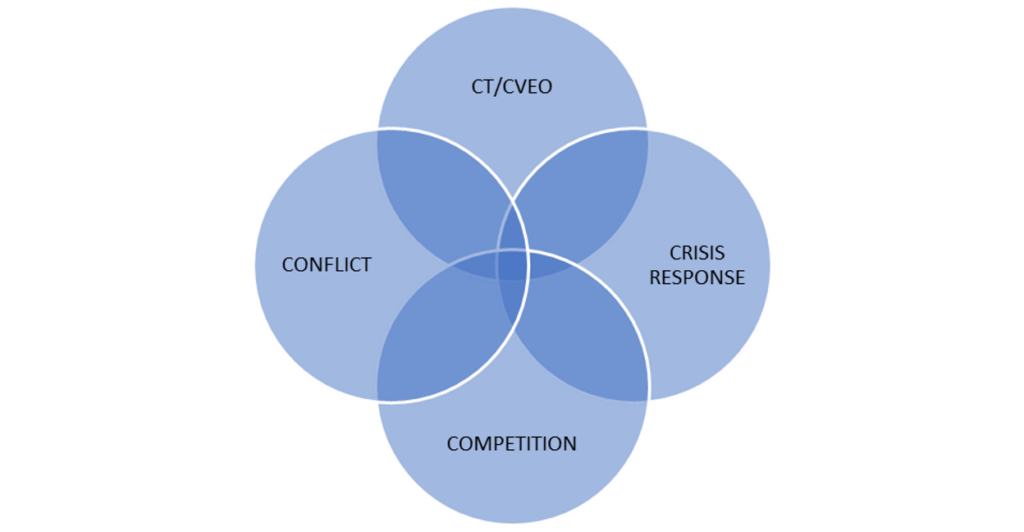

USSOF is challenged to balance both future operations, such as campaigning in the information and cognitive domains, while also managing ongoing threats from VEOs, hostage rescue, and proxy wars, which simultaneously place operational demands on USSOF. While CT and COIN operations may not be as relevant for strategic competition today, SOF’s crisis response and CVEO will remain key competencies. To fit within this complex and taxing operating landscape, USSOF’s mission and priorities must be integrated across the DOD, and special operations must be viewed as an offering falling within each respective service, rather than as a separate entity. This need is complicated by the reality that USSOF components are distinctive across the military, filling disparate roles and viewed differently by their parent services.

Applying SOF’s strengths in new ways

USSOF must play to its strengths, applying its operational approaches from the GWOT to new problem sets in the context of strategic competition. This includes operating in new domains, applying and accelerating emerging technologies, and building upon core activities that were de-prioritized over the past two decades. USSOF excels at operating in denied and niche environments. For instance, USSOF is uniquely trained to operate in underground tunnels and facilities, which otherwise pose a threat to situational awareness and target execution. The salience of this environment is illustrated by the current conflict in Gaza, where underground tunnels serve as a strategic vantage point for Hamas and complicate Israeli operations and US efforts to rescue US hostages held by terrorists. The ability to operate underground is just one example of how USSOF can fill an operational gap for the US military, as USSOF is the only component that has the highly specialized tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) for operating in those environments.

How can SOF’s strengths be applied in new ways? First, USSOF’s ability to quickly adapt to new environments could be further leveraged in strategic competition. For example, USSOF should enhance its capabilities in cyber, space, and undersea warfare—all with a foundation of flexible doctrine and tactical innovations—in order to compete with China’s approach to “informatized warfare” and its rapid technology development.24Dean Cheng, Cyber Dragon: Inside China’s Information Warfare and Cyber Operations (New York: Bloomsbury, 2016). Additionally, WARCOM (the naval component of USSOCOM) is undergoing a modernization effort in two key underwater systems—namely the shallow-water combat submersible and the dry-combat submersible, which are both critical to moving SEALS through oceans. These modernizations provide enhanced situational awareness to operators, improved range, increased payload, better speed and loitering time, and a modernized command-and-control architecture—all of which will enable USSOF to leverage undersea capabilities for strategic competition.

Another example exists in the Arctic, where MARSOC is uniquely positioned to operate in extreme weather conditions and address burgeoning security challenges that continue to arise as polar ice melts. However, to effectively operate there, MARSOC’s Civil Affairs expertise must be bolstered to fully enhance its role in support of Arctic security. USAF SOF trains in Alaska and with European Arctic countries to support extreme weather operations like search and rescue. As Chinese and Russian activity and presence above the Arctic Circle increase—including under the auspices of science, energy, and environmental missions—USSOF intelligence and access will be invaluable.

Second, USSOF’s Civil Affairs and PSYOPs components require further attention to be fully harnessed in strategic competition. Civil Affairs is a tightly stretched, low-density function, with just one brigade of USSOF Civil Affairs force structure in the entire military. That brigade houses capabilities such as economic analysis, special collections, observations and advanced intelligence gathering, penetrations of transnational criminal organizations (TCO), training and cultural immersion, and placement and access into adversarial commercial and government networks. If resourced effectively, Civil Affairs can take on more tasks, such as building civil-military reconnaissance in politically sensitive areas, helping legitimize local governing powers in contested regions, or helping respond to natural disasters and humanitarian crises (which will only become more prevalent with climate change). Additionally, MARSOC’s Civil Affairs strength is in its language and cultural skills. For instance, MARSOC has been very active in the Philippines for many years, and the expanded partnership between the United States and the Philippines is evidence of this investment paying off. Such Civil Affairs activities are worth increased investment, particularly with key partners in the Indo-Pacific.

Finally, the technological and cognitive performance solutions required for USSOF’s—and the Joint Force’s—success will continue to evolve in response to the growing arsenals of US adversaries like China. On today’s battlefield, USSOF will need to achieve cognitive overmatch—the “ability to dominate the situation by making informed decisions faster than the opponent”—which can be dramatically enhanced with the aid of advanced technologies like artificial intelligence. The hyper-enabled operator of the future must be “empowered by technologies that enhance the operator’s cognition at the edge by increasing situational awareness, reducing cognitive load, and accelerating decision making.” As such, special operators will need to operate with the support of an interconnected network of sensors, a robust communications architecture, and human-machine interfaces. Through its Preservation of the Force and Family (POTFF) program, USSOF has placed increased attention on cognitive performance and brain health, which it sees as necessary “to operate in an increasingly complex, information-rich environment.” These investments have led to demonstrated improvements in “self-regulation, cognitive processing speed, and sustained attention” for participants. At the same time, USSOF has partnered with DOD Health Affairs to improve its traumatic brain injury (TBI)-prevention efforts. Investing in the cognitive domain is critical to ensure special operators are well-prepared for, and avoid accepting undue risk in, a complex operating environment.25Maier and Fenton, “Statement for the Record.”

Knowing what success looks like

One of USSOF’s biggest challenges in a transforming security environment is constructing its identity in 2024 and beyond. This requires USSOF and DOD leadership to ask and respond to ambitious questions regarding the requirements of future warfare and the role of USSOF.

Who is the special operator in 2024 and beyond?

As USSOF’s role in strategic competition evolves, so does the face of the special operator. The special operator of 2024 may be a cyber operator gaining virtual placement and access, rather than the Hollywood depiction of the frontline operator deployed in the kinetic, physical battle. The SOF operator who is culturally immersed in a region or area that holds strategic value plays a key role in enabling US activities and intelligence. So do the SOF experts in space, AI, engineering, or physics support operations, who bring invaluable cognitive power and technological know-how. Although enablers are frequently perceived as secondary to operators, their work is often high-end and critical to mission success, making them a focal point for current investment needs. Additionally, as USSOF continues to adapt, gender may play a valuable role in military competition, education, negotiations, and training. For instance, an all-female special-operations team (Operational Detachment Alpha, or ODA), can engage with women in local populations, like Afghanistan, in different and valuable ways than an all-male team. Gender diversity allows SOF to operate in varied roles, opening up new opportunities where gender may lead to favorable outcomes.

How can USSOF measure its own success?

Landing on clear metrics or conducting a net assessment to quantify the success of special operations is nearly impossible, as it is difficult to measure the effectiveness of preventing something from occurring over time. Despite this difficulty, USSOF must internally define a clear mission for strategic competition and establish a tracking mechanism to assess whether it is making progress toward its goals. In particular, the DOD should place emphasis on developing MISO/influence campaigns with measurable criteria that focus on output, not just input, to ensure that such activities are truly changing behavior and perceptions of the target audience. Moreover, USSOF must be able to effectively articulate its value and successes to the public, Congress, the DOD at large, and the wider interagency, while protecting some of its more unique contributions that should remain classified. For example, while the taglines of “creating dilemmas” and “imposing costs” are useful in their simplicity for describing USSOF, they do not give policymakers a clear framework to understand how USSOF achieves a desired impact. USSOF could instead articulate its success by citing deliberate campaigns to disrupt and frustrate an adversary’s strategy or operations, with the ultimate goal of undermining an adversary’s confidence that its military can win decisively. Such an articulation could mirror RAND’s 2023 “Strategic Disruption” framework for five pillars of disruption (resist, support, influence, understand, target), which helps communicate the role USSOF plays in achieving strategic effects as defined by measurable results.

How should USSOF prioritize its core activities for strategic competition?

Joint Force decision-makers should consider the myriad ways USSOF can increasingly support strategic competition and work with ASD SO/LIC and USSOCOM to re-prioritize some of USSOF’s core activities to match the needs of strategic competition. This prioritization could see an increased role for USSOF pre-conflict in China and Russia’s near-abroad—the Indo-Pacific and Europe—and a deeper role for USSOF during conflict in China and Russia’s far-abroad, such as AFRICOM, SOUTHCOM, and other areas of responsibility.

USSOF cannot establish its own priorities in a vacuum—it will prioritize what the Joint Force needs. But ASD SO/LIC and USSOCOM can align to effectively communicate their vision for SOF’s role in strategic competition within the Pentagon. This will likely include identifying where USSOF is insufficiently prepared for strategic competition and developing methodologies to test and measure the performance of various activities in the context of competing with China and Russia.

As discussed, rebalancing to strategic competition must be done in balance—crisis response (CR) will remain a top priority for USSOF, in which countering VEOs remains key as they frequently cause crises that require response. CT and COIN missions have value, and USSOF’s ability to counter VEOs allows the broader force to stay focused on near-peer competitors. With that being said, USSOF should outwardly view its CT, COIN, counternarcotic (CN), and partner capacity-building activities in a new light, as contributing factors to competition by maintaining influence and trust with partners.

USSOF should also preemptively invest in Civil Affairs, MISO, and intelligence, which are actively engaged prior to conflict. A good example of USSOF’s leadership approach within the Pentagon is its centralization and special interest-item designation of MISO funding, which demonstrates congressional and civilian leadership exercising oversight, control, and authority over the military. The role of ASD(SO/LIC) in advocating for and prioritizing MISO efforts is important to ensure this function remains funded.

How can USSOF and the services find new opportunities for better integration?