The impact of Western sanctions on Russia and how they can be made even more effective

Key points

- While Western sanctions have not succeeded in forcing the Kremlin to fully reverse its actions and end aggression in Ukraine, the economic impact of financial sanctions on Russia has been greater than previously understood.

- Western sanctions on Russia have been quite effective in two regards. First, they stopped Vladimir Putin’s preannounced military offensive into Ukraine in the summer of 2014.

- Second, sanctions have hit the Russian economy badly. Since 2014, it has grown by an average of 0.3 percent per year, while the global average was 2.3 percent per year. They have slashed foreign credits and foreign direct investment, and may have reduced Russia’s economic growth by 2.5–3 percent a year; that is, about $50 billion per year. The Russian economy is not likely to grow significantly again until the Kremlin has persuaded the West to ease the sanctions.

Contents

What is the problem with Putin’s regime?

Harmful international repercussions of Russia’s authoritarian kleptocracy

The dominant Western response to Putin’s aggression was sanctions

The impact of the Western sanctions

Problems with the sanctions

How could the sanctions administration be improved?

The first Biden steps on Russia sanctions

Effective sanctions require more transparency, enforcement, and international cooperation

Conclusions

Want to read this offline?

Data for the key points obtained from:

“Russia Statistics,” Bank of Finland Institute for Economies in Transition, accessed March 20, 2021, https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiOWQwM2VjNTUtZTdmZC00N2IyLTkyNTMtY2MwYjMxYjdhYzc0IiwidCI6ImVkODlkNDlhLTJiOTQtNGFkZi05MzY0LWMyN2ZlMWFiZWY4YyIsImMiOjh9&pageName=ReportSection0670cd3fe87e80037c8d. The International Monetary Fund assesses that Russia’s gross domestic product has grown by 0.5 percent in total during the seven years 2014–2020. “World Economic Outlook Database, October 2020,” International Monetary Fund, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2020/October/weo-report?a=1&c=001,&s=NGDP_RPCH,&sy=2013&ey=2020&ssm=0&scsm=1&scc=0&ssd=1&ssc=0&sic=0&sort=country&ds=.&br=1.

When analyzing a Western policy on Russia, one must first assess the nature of Russia’s government.1This report follows the line of Daniel Fried and Alexander Vershbow, How the West Should Deal with Russia, Atlantic Council, November 23, 2020, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/russia-in-the-world/ The authors call it “kleptocratic” or “neopatrimonial” autocracy, as such regimes sustain loyalty of elites and population through the redistribution of benefits and spoils. The two main objectives of Vladimir Putin’s system are to maintain power and to enrich a narrow elite. The Kremlin’s foreign policy should be seen from this perspective. It is designed to promote the interests of the current Kremlin elite, not the Russian nation. One means of doing so has been small victorious wars, as described by a century-old Russian term. As the Russian economy has barely grown since 2014, the Kremlin has become more cautious with major real warfare. Instead, it pursues cheaper, so-called hybrid warfare, such as cyberattacks and assassinations.

For the West, a real war with Russia has been out of question. But, since Russia’s aggression in Ukraine in 2014, the West has felt a need to do something substantial to impede Russian foreign aggression. Its natural choice has been sanctions. The West has focused on two kinds of sanctions: financial sanctions and personal sanctions on human-rights violators and corrupt businessmen working for the Kremlin. In addition, the West has introduced some restrictions on the export of technology, while it has abstained from the previously common trade sanctions. In general, sanctions are becoming more diverse, with the share of trade sanctions falling, while financial and visa sanctions are becoming more popular.2Gabriel Felbermayr, et al. “The Global Sanctions Data Base,” European Economic Review, October 2020, 129, https://voxeu.org/article/global-sanctions-data-base

This report aims to assess how effective Western sanctions on Russia have been in macroeconomic terms, and what could be done to render them more effective. Its focus is the impact of sanctions on gross domestic product (GDP). The authors argue that while Western sanctions have not succeeded in forcing the Kremlin to fully reverse its actions and end aggression in Ukraine, their effect has been quite substantial with regard to the weakening of the Russian economy and stopping further military aggression. The financial sanctions had the greatest impact on Russian GDP, by restricting Russia’s access to foreign capital, including credits to both the government and the private sector, as well as foreign direct investment (FDI). A secondary impact of the financial sanctions was enticing the Kremlin to pursue a more restrictive fiscal and monetary policy than would have been ideal for economic growth.

This report distinguishes microeconomic effects of sanctions as well, but does not try to quantify them. When passing judgment on the effect of sanctions, the authors make the following distinctions: Did the sanctions roll back objectionable policies, contain them, or deter Russia from further objectionable policies? First, however, it is important to assess the real problem with Putin’s regime and its international repercussions.

What is the problem with Putin’s regime?

Putin has proven himself a skillful politician. In his first term, 2000–2004, he was everything to everybody, and successfully consolidated power. In his second term, 2004–2008, he extended his control to the big state companies by appointing his loyalists as their chief executives. He has continuously stripped massive amounts of assets from the big state companies, to the benefit of his cronies. Since 2009, he has ignored economic growth, and the standard of living has fallen since 2014. When Putin returned as president in 2012, he rendered his regime more repressive, and its repression is rising further.

Putin’s way to power was marked by a series of controversies including dubious explosions of buildings that cost a few hundred Russian citizens their lives,3Alexander Litvinenko and Yuri Felshtinsky, Blowing Up Russia: The Secret Plot to Bring Back KGB Terror (London: Gibson, 2007); John Dunlop, The Moscow Bombings of September 1999: Examinations of Russian Terrorist Attacks at the Onset of Vladimir Putin’s Rule, second edition (New York: Columbia University Press, 2014). a war in Chechnya, and a row of serious human-rights violations.4Peter Baker and Susan Glasser, Kremlin Rising: Vladimir Putin’s Russia and the End of Revolution (New York: Scribner, 2005); Luke Harding, Mafia State (London: Guardian, 2011); Masha Gessen, The Man Without a Face: The Unlikely Rise of Vladimir Putin (New York: Riverhead Books, 2012); Karen Dawisha, Putin’s Kleptocracy: Who Owns Russia? (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2014).

Russia’s political stability under Putin must not be exaggerated. The country has experienced several waves of popular unrest. In 2005, senior citizens protested against a pension reform. And, in 2011–2012, a series of protests shaked Moscow and several regions in response to an obviously fraudulent election in which Putin returned to the presidency after a brief stint as prime minister. Since 2019 another series of country-wide protests have taken place across the multiple Russia’s regions. But, nothing seemed to seriously shake Putin. He has responded by gradually turning his regime more repressive.

His presidency has been marked by numerous murders seemingly initiated by the Kremlin, such as those of investigative journalist Anna Politkovskaya in Moscow in 2006, Federal Security Service (FSB) defector Alexander Litvinenko in London in 2006, and opposition leader Boris Nemtsov outside of the Kremlin in 2015—and many other completed or failed attempts at people’s lives.5Luke Harding, A Very Expensive Poison: The Assassination of Alexander Litvinenko and Putin’s War with the West (London: Vintage, 2017). Harding’s Mafia State is possibly the best presentation of Putin’s violence, but there are many others. John Dunlop wrote an excellent book on Boris Nemtsov’s assassination: John Dunlop, The February 2015 Assassination of Boris Nemtsov and the Flawed Trial of His Alleged Killers (Stuttgart: Ibidem, 2019). Such murders have also been revealed or suspected abroad, in Berlin, London, Qatar, Vienna, and Washington.6Steven Lee Myers, “Qatar Court Convicts 2 Russians in Top Chechen’s Death,” New York Times, July 1, 2004, https://www.nytimes.com/2004/07/01/world/qatar-court-convicts-2-russians-in-top-chechen-s-death.html; Heidi Blake, et al., “From Russia With Blood,” Buzzfeed, June 15, 2017, https://www.buzzfeed.com/heidiblake/from-russia-with-blood-14-suspected-hits-on-british-soil; Jason Leopold, et al., “The US Death of Putin’s Media Czar Was Murder, Trump Dossier Author Christopher Steele Tells the FBI,” Buzzfeed, March 27, 2018, https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/jasonleopold/christopher-steele-mikhail-lesin-murder-putin-fbi; “Germany Accuses Russia of Berlin Park Assassination,” BBC, June 18, 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-53091298; Andrew Kramer, “In a Death, Details of More Russian Murder-for-Hire Plots,” New York Times, July 9, 2020, https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/09/world/europe/chechnya-russian-murder-vienna.html Bellingcat has uncovered that the FSB maintains a murder squad.7“Navalny Poison Squad Implicated in Murders of Three Russian Activists,” Bellingcat, January 27, 2021, https://www.bellingcat.com/news/uk-and-europe/2021/01/27/navalny-poison-squad-implicated-in-murders-of-three-russian-activists/ Assassinations at home and abroad appear to be Putin’s standard procedures.

A man holds a portrait of the killed journalist Anna Politkovskaya as a woman lays flowers during a commemorative rally in St.Petersburg, October 7, 2009. REUTERS/Alexander Demianchuk

To understand how Putin’s regime works, one needs to first understand its neopatrimonial nature. In regimes like Putin’s, personalistic rulers hold on to power through a system of personal patronage, which is based on informal relations of loyalty and personal connections made possible by the weakness of formal institutions in such societies.8Vladimir Gelman, “The Vicious Circle of Post-Soviet Neopatrimonialism in Russia,” Post-Soviet Affairs 32, 5, 2016, 455–473; Maria Snegovaya, “The Taming of the Shrew: How the West Could Make the Kremlin Listen,” European View, 2021, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/17816858211005634 Similar regimes—which proliferated in African, Middle Eastern, and post-Soviet countries—tend to draw legitimacy primarily from payoffs to elites and the broader population.9Maria Snegovaya, “Neo-Patrimonialism and the Perspective for Democratization,” Notes of The Fatherland 6, 2013, 135–145; Kirill Rogov and Maria Snegovaya, “The Outcomes of Political Liberalization: Non-Democracies in Eurasia and Africa,” work in progress.

What the authors mean by “neopatrimonial autocracy” is equivalent to kleptocratic autocracy, a regime that rests largely on its leader’s ability to hold on to power by bribing politically pivotal groups to ensure that he can remain in power against challenge.10Dawisha, Putin’s Kleptocracy; Anders Åslund, Russia’s Crony Capitalism: The Path from Market Economy to Kleptocracy (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2019); Gessen, The Man Without a Face; Catherine Belton, Putin’s People (New York: FSG, 2020); Daron Acemoglu, Thierry Verdier, and James A. Robinson, “Kleptocracy and Divide-and-Rule: A Model of Personal Rule,” Journal of the European Economic Association 2, 2–3, 162–192, https://economics.mit.edu/files/4462 To sustain the loyalty of the elites, the leaders of neopatrimonial regimes allow their elite members access to illicit rents, patronage, and corruption.11Michael Bratton and Nicholas Van de Walle, Democratic Experiments In Africa: Regime Transitions in Comparative Perspective (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997). Neopatrimonial presidents make “little distinction between the public and private coffers, routinely and extensively dipping into the state treasury for their own political need.”12Ibid., 66. Accordingly, Putin’s regime has established a system of enrichment for his closest circles and elites that relies on extraction of resources from the public coffers through privileged public procurement, manipulation of stock, asset stripping, and privileged trade.13Marshall Goldman, Petrostate. Putin, Power, and the New Russia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010); Neil Robinson, ed., “The Context of Russia’s Political Economy,” The Political Economy of Russia (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2012), 15–50; Åslund, Russia’s Crony Capitalism.

Under a similar logic, when it comes to the broader population, neopatrimonial regimes buy off its loyalty through the redistribution of benefits and spoils.14Nicholas Van de Walle, “The Path from Neopatrimonialism: Democracy and Clientelism In Africa Today,” Mario Einaudi Center For International Studies, 2007, https://ecommons.cornell.edu/handle/1813/55028 Thus, to secure support of the Russian population, Kremlin politicians redistribute resources to it through payments from the state coffers in the form of pensions, allowances, and wages.15Vasyl Kvartiuk and Thomas Herzfeld, “Redistributive Politics in Russia: The Political Economy of Agricultural Subsidies,” Comparative Economic Studies 63, 2020, 1–30; Snegovaya, “The Taming of the Shrew.”

A constant flow of rents ensures the sustainability of such systems. These rents come from taxes, natural resources, state-owned companies’ revenues, asset stripping, and public procurement—anything but normal profits on the market. These rents are highly concentrated to the ruling elite, though some are redistributed to various population groups to ensure their continuous loyalty. External shocks to rent flows, such as falling oil prices or financial sanctions, might threaten such regimes, and lead to growing dissatisfaction among the elites and the broader population.16Bratton and Van de Walle, Democratic Experiments in Africa; Snegovaya, “Neo-Patrimonialism and the Perspective for Democratization.”

If neopatrimonial rulers feel seriously worried about suffering losses of rents from external shocks, they might be more inclined to agree to concessions with the West. Therefore, a successful sanctions policy targeting neopatrimonial regimes should aim to decrease the flow of rent that is at the disposal of such regimes.17Snegovaya, “The Taming of the Shrew.”

Harmful international repercussions of Russia’s authoritarian kleptocracy

As an authoritarian kleptocrat, Putin is most of all scared of democracy, but also of transparency and the traditional freedoms of association and the media. The real threat to his power does not come from NATO or the West, but from his own people. Not even a strongman such as Putin is safe. His first big shock was the wave of color revolutions in Georgia in 2003, Ukraine in 2004, and 2005 in Kyrgyzstan.18Maria Snegovaya, “Reviving the Propaganda State,” Center for European Policy Analysis, January 2018, https://cepa.org/reviving-the-propaganda-state; Keith Darden. Russian Revanche: External Threats & Regime Reactions. Daedalus. April, 2017,146(2):128-41. He responded by legislating strict controls over civil society in Russia in 2005. In February 2007, he turned his fury against the United States in his big anti-American speech in Munich.19Vladimir V. Putin, speech and following discussion at the Munich Conference on Security Policy, February 10, 2007, www.kremlin.ru.

This speech may be seen as a trial balloon. Putin was received with applause in Munich. Surprisingly, he was even invited to the NATO summit in Bucharest in April 2008, where he declared that Ukraine was not a country, and NATO failed to offer Ukraine and Georgia Membership Action Plans.20“What Precisely Vladimir Putin Said at Bucharest,” Zerkalo Nedeli, April 19, 2008. Perceiving the West as toothless, Putin opted for small wars to whip up Russian nationalism and enhance his domestic popularity. His five-day war in Georgia in August 2008 was a great popular success in Russia. For the first time ever, his popularity rating reached 88 percent, according to the independent pollster Levada Center.21“From Opinion to Understanding,” Levada Center, accessed March 13, 2021, https://www.levada.ru/en/ratings/

Putin’s obvious conclusion was that small victorious wars were the best means for him to boost his popularity, and authority, at home. Through its Revolution of Dignity from November 2013–February 2014, Ukraine delivered another great democratic shock to Putin, but it also presented him with an opportunity. Now he was prepared militarily. He seized and annexed Crimea. Russians loved it, because to them Crimea was the Soviet holiday paradise lost. Once again, Putin’s popularity rating rose, this time to 86 percent.22Mikhail Sokolov and Claire Bigg, “Putin Forever? Russian President’s Ratings Skyrocket Over Ukraine,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty,January 3, 2014, https://www.rferl.org/a/russia-putin-approval-ratings/25409183.html; Andrei Kolesnikov, “Five Years After Crimea, Russia Has Come Full Circle at Great Cost,” Moscow Times, February 5, 2019, https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2019/02/05/five-years-after-crimea-annexation-russia-has-come-full-circle-at-great-cost-op-ed-a64393. Over the past three years, however, it has declined to 64 percent, and the public’s trust in him has fallen to half that. While a liberal third of the population opposes Putin, another third supports him, and the remaining third is agnostic.23“From Opinion to Understanding.”

Putin has developed a peculiar technique of using Russian businessmen close to the Kremlin in his more odious foreign policy. By delegating military activities abroad to Russian businessmen, he can exploit their entrepreneurship, save money, and claim plausible deniability. One significant example was the investment banker Konstantin Malofeev, who financed private separatist activities in eastern Ukraine in 2014, which earned him US sanctioning. “Malofeyev is being designated because he is responsible for or complicit in, or has engaged in, actions or polices that threaten the peace, security, stability, sovereignty, or territorial integrity of Ukraine and has materially assisted, sponsored, or provided financial, material, or technological support for, or goods or services to or in support of the so-called Donetsk People’s Republic.”24“Treasury Targets Additional Ukrainian Separatists and Russian Individuals and Entities,” US Department of the Treasury, December 19, 2014. The US sanctioning seems to have been effective, because Malofeeev has disappeared from public view.

A more important private Kremlin operator is Yevgeny Prigozhin. His private military company Wagner operates in Syria, Libya, the Central African Republic, and elsewhere in Africa. The US “Treasury is targeting the private planes, yacht, and associated front companies of Yevgeniy Prigozhin, the Russian financier behind the Internet Research Agency and its attempts to subvert American democratic processes.”25“Treasury Targets Assets of Russian Financier Who Attempted to Influence 2018 U.S. Elections,” US Department of the Treasury, October 30, 2020, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm787#:~:text=%E2%80%9CTreasury%20is%20targeting%20the%20private,to%20subvert%20American%20democratic%20processes; Carol Morello, “U.S. Imposes Sanctions on Russian Tycoon, Along With His Yacht and Private Jets,” Washington Post, September 30, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/us-sanctions-russian-tycoon-along-with-his-yacht-and-private-jets/2019/09/30/0fc7cd72-e38d-11e9-a6e8-8759c5c7f608_story.html

Even more important is Oleg Deripaska, a major Russian oligarch closely connected with the Kremlin, who figured prominently in the Robert Mueller investigation. The United States designated him for “for having acted or purported to act for or on behalf of, directly or indirectly, a senior official of the Government of the Russian Federation.” He has “claims to have represented the Russian government in other countries.”26“Treasury Designates Russian Oligarchs, Officials, and Entities in Response to Worldwide Malign Activity,” US Department of the Treasury, April 6, 2018, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/sm0338

Another prominent Kremlin oligarch is Igor Sechin, the chief executive of state-owned Rosneft, who is thought to be effectively in charge of Russian policy on Venezuela.27Vladimir Isachenkov and Joshua Goodman, “Rosneft Hands Venezuelan Oil Business to Russian State Firm,” Associated Press, March 28, 2020, https://apnews.com/article/7d15631558f3caca5c0fe80eef2cdf23; Alexander Gabuev, “Russia’s support for Venezuela has deep roots,” The Financial Times, February 3, 2019, https://www.ft.com/content/0e9618e4-23c8-11e9-b20d-5376ca5216eb In Georgia, the Kremlin benefits from the politically dominant Russian-Georgian oligarch Bidzina Ivanishvili.28James Kirchick, “A Russian Victory in Georgia’s Parliamentary Election,” The Wall Street Journal, October 2, 2012, https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10000872396390444592404578032293439999654 In Greece, the Soviet-born Ivan Savvidis serves Kremlin causes.29Helene Cooper and Eric Schmitt, “U.S. Spycraft and Stealthy Diplomacy Expose Russian Subversion in a Key Balkans Vote,” The New York Times, October 9, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/09/us/politics/russia-macedonia-greece.html

Deripaska maintained close links with the Kremlin, and Donald Trump’s former campaign manager Paul Manafort began working for him in 2005. Manafort’s deputy Rick Gates explained to the FBI: “Deripaska used Manafort to install friendly political officials in countries where Deripaska had business interests. Manafort’s company earned tens of millions of dollars from its work for Deripaska and was loaned millions of dollars by Deripaska as well.30”Special Counsel Robert S. Mueller, III, “Report on the Investigation into Russian Interference in the 2016 Presidential Election, [Mueller Report], Vol. I,” US Department of Justice.

The Mueller Report also illustrates how Putin has reduced the freedom of the oligarchs. Many fathom that wealth brings freedom, but the Mueller Report shows that the opposite is true in Russia. The richer Russian oligarchs become, the more subservient they must be to the Kremlin in order to preserve their fortunes.

Georgia’s former Prime Minister Bidzina Ivanishvili smiles at a rally of ruling Georgian Dream party after the parliamentary elections in Tbilisi, Georgia, October 8, 2016. REUTERS/David Mdzinarishvili

The dominant Western response to Putin’s aggression was sanctions

Sanctions are supposed to be only one tool of foreign policy, but in recent years they have become the dominant tool. The United States has not used diplomacy as much as it could, and it has offered limited development and humanitarian aid. After the costly, but unfortunate, wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, Americans have precluded the deployment of significant numbers of troops. Sanctions have the added advantage that they do not require budget allocation. Furthermore, because the US economy is comparatively self-contained, the cost of sanctions tends to be greater for other countries closer to the sanctioned country. Thus, sanctions have become the default option in foreign conflicts.

The empirical literature shows that the efficacy of sanctions varies greatly by country, aim, and the sanctioning alliance. The more limited the aim and the broader the alliance, the greater the probability of success. In a thorough empirical study of two hundred and four cases of modern Western sanctions, Gary Hufbauer and his co-authors concluded that sanctions were “at least partially successful in 34 percent of the cases” documented, so “the bald statement ‘sanctions never work’ is demonstrably wrong.31”Gary Clyde Hufbauer, et al.. Economic Sanctions Reconsidered (Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2009), 159.

Most sanctions are not very effective, but substantial knowledge has been gathered about what works. Sanctions should deter, punish and hopefully reverse bad behavior. Narrowly targeted and clearly-defined sanctions are usually more effective than broad sanctions that aim, for example, at regime change. The more countries that participate, the more effective sanctions tend to be.32Ibid. Therefore, the Biden administration is right in its intent to return to far-reaching coordination with European allies in its Russia sanctions. Finally, sanctions must be enforced to be effective.

During the Cold War, the United States and the rest of the West maintained severe technology sanctions on the Soviet Union, which kept the country technologically backward. In 1974, the United States adopted the Jackson-Vanik Amendment to the US Trade Law. It insisted on the Soviet Union allowing the emigration of Jews as the US condition for maintaining normal trading relations. Soviet leaders respected the amendment, accepting a massive emigration of Soviet Jerws, and the United States reviewed the Soviet compliance annually.

Since 2012, Russia has become subject to new Western sanctions because of its increasing violation of international agreements. Some have been unilateral US sanctions, while Western allies have joined in others. None of the sanctions has been universal or sanctioned by the United Nations (UN). Currently, the United States has about fifteen different sanctions programs impacting Russia, and several others have been proposed. Sensibly, the Biden administration has called for a review of US Russia sanctions.33“US Sanctions on Russia (R45415—Version: 9),” Congressional Research Service, January, 17, 2020, 7–35, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/details?prodcode=R45415

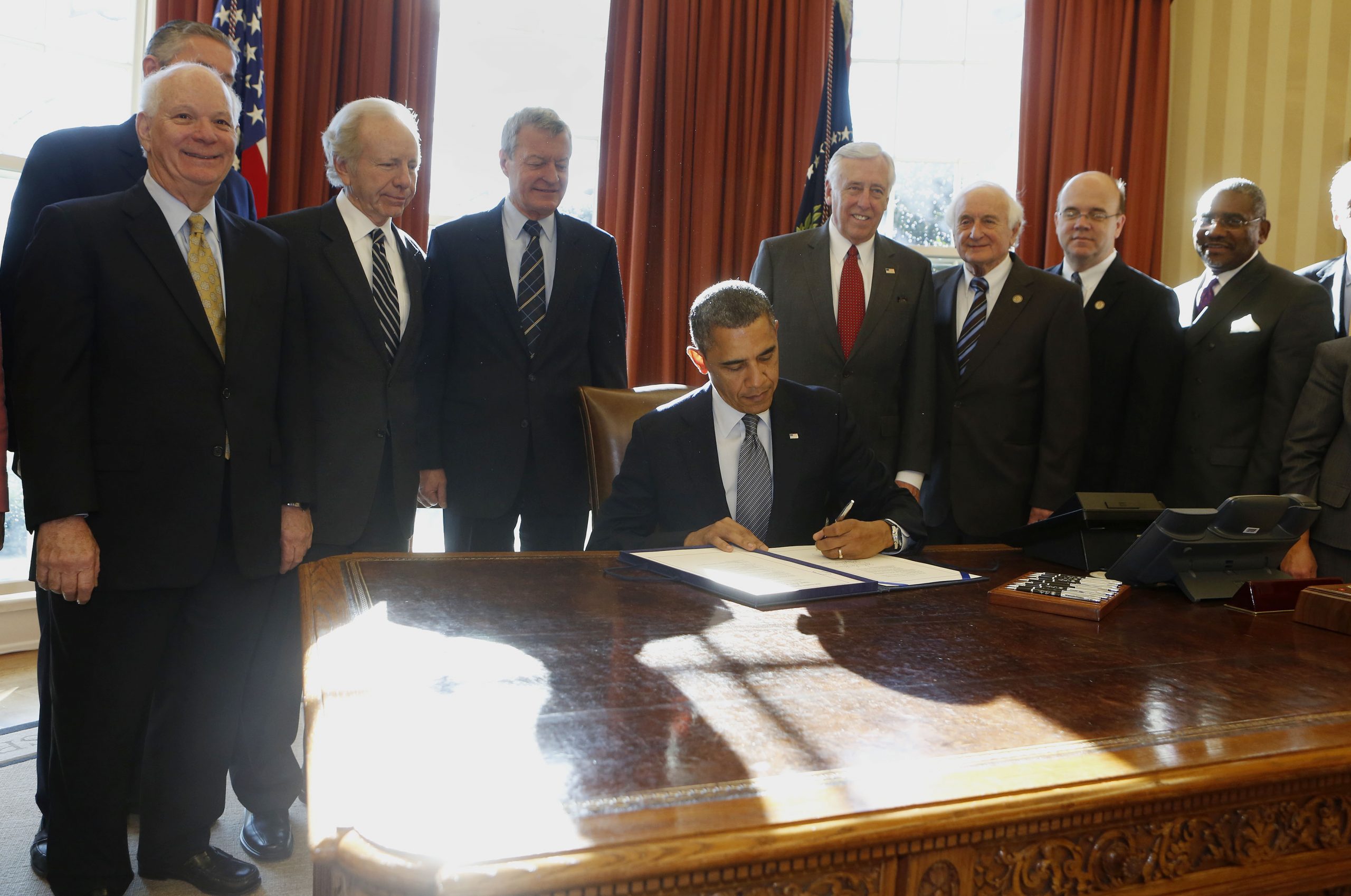

The first US sanction targeting Russia after the Cold War was the Sergei Magnitsky Rule of Law Accountability Act of 2012, which became law as the Jackson-Vanik amendment was finally set aside as Russia joined the World Trade Organization (WTO).34“Russia and Moldova Jackson-Vanik Repeal and Sergei Magnitsky Rule of Law Accountability Act of 2012,” July 7, 2012, https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/112/hr6156/text The Magnitsky Act targets violators of human rights in Russia. Under its terms, more than fifty Russian officials and private helpers, and some other entities, have been sanctioned. They are being refused visas to the United States, and their assets in the United States are supposed to be frozen. The acts of these culprits are illegal according to Russian law, but the Kremlin defends its criminal officials and became very upset about the Magnitsky Act—which indicates that it is effective.35Julia Ioffe, “Why Does the Kremlin Care So Much About the Magnitsky Act?” Atlantic, July 27, 2017, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2017/07/magnitsky-act-kremlin/535044/

In December 2016, the US Congress broadened the Magnitsky Act to the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act to cover the whole world, no longer singling out Russia, applying the same principles globally, and targeting corrupt and tyrannical top officials and tycoons.36Committee on Foreign Relations. Bill, Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act §. S. 284 (2016), https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/senate-bill/284/text The two Magnitsky Acts seem ideal forms of sanctions. They have become popular with the nongovernmental organization (NGO) community, while being feared by big crooks. The United States has sanctioned a few Russians under “GloMag.”

US President Barack Obama signs into law H.R. 6156, the Russia and Moldova Jackson-Vanik Repeal and Magnitsky Rule of Law Accountability Act, on December 14, 2012. From L-R are: US Sen. Ben Cardin, US Sen. Joe Lieberman, US Sen. Max Baucus, Obama, US Rep. Steny Hoyer, US Rep. Sandy Levin, US Rep. Jim McGovern, and US Rep. Gregory Meeks. REUTERS/Larry Downing

Another group of sanctions are not focused on Russia per se, but concern other countries—notably, Iran, North Korea, Syria, and Venezuela. Russian companies, state-owned or private, are often involved in these illicit operations, but these sanctions programs do not belong to a Russia sanctions discussion.

Two big US sanctions programs are linked to Russian aggression in Ukraine: first toward the Russian occupation of Crimea in February–March 2014, and then against the Russian military aggression in eastern Ukraine from July 2014. Both have been coordinated with the European Union (EU) and some other allies, and they are being maintained and gradually updated.

The US and EU sanctions on Crimea since March 2014 are straightforward; they sanction all the main political culprits and companies that do significant business with Crimea, to maximize the cost to Russia of its occupation of Crimea. This is a sensible and well-functioning sanctions program that should be maintained and policed.

A novelty of the March 2014 US sanctions was that they hit Putin’s cronies, four businessmen from St. Petersburg who were old close friends of Putin and had become billionaires entirely because of their friendship. Putin complained at least five times in public about the West sanctioning his close friends, showing that these sanctions hit hard.37Åslund, Russia’s Crony Capitalism, 148–152.

In July 2014, Russia sent special forces into Ukraine, as the East Ukrainian rebels were collapsing militarily. On July 16, the United States responded with new, much more far-reaching sanctions. Two weeks later, the EU followed suit, after a Russian missile shot down a Malaysian airplane and killed two hundred and ninety-eight civilians, two thirds of whom were Dutchmen. Apart from applying to the people and entities responsible, the sanctions included sectoral sanctions on finance, oil technology, and defense technology. This paper focuses on the financial sanctions that have had the dominant macroeconomic impact, keeping financial resources out of Russia.

In 2017, after Trump became president, the US Congress adopted the Combating American Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA) with overwhelming majority support. It forced the administration to seek congressional support in case it wanted to lift sanctions absent a settlement in Ukraine. The aim was to defend the US sanctions on Russia against Trump, who opposed them and praised Putin. The most exciting section in this law (Section 241) called for the development of a report naming oligarchs close to the Kremlin. The administration reportedly prepared a high-quality classified report, but undermined its impact by releasing an ill-prepared unclassified report that lacked credibility. The Trump administration hesitated after that, but, by April 2018, the political embarrassment became too great, so it sanctioned seven major Russian oligarchs. For the first time since July 2014, Moscow was shocked, and the stock exchange fell by 11 percent in one day.38Ben Chapman and Oliver Carroll, “Russia Stock Market Crashes 11% after US Imposes Sanctions on Oligarchs Linked to Kremlin,” Independent, April 10, 2018, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/news/russia-stock-market-latest-updates-us-sanctions-oligarchs-kremlin-putin-deripaska-a8296536.html

The United States has also imposed sanctions on Russia for cybercrimes and election interference, and the Department of Justice has opened criminal cases against suspected culprits. In 1991, the United States adopted a special law, the Chemical and Biological Control and Warfare Elimination Act, on sanctions for such violations. It was designed for Iraq, but generally formulated. In 2018, because of Russia’s use of chemical weapons against former intelligence officer Sergei Skripal in the United Kingdom, the United States imposed sanctions on Russia under this act. In 2019, it used the act to prohibit US financial institutions from participating in the primary issuance of non-ruble-denominated sovereign bonds. A natural second step after the FSB use of chemical weapons against Alexei Navalny would be to sanction all issuance of Russian government debt, including debt issued in rubles. Some argue that the West should also sanction secondary debt, prohibiting Western institutions from holding Russian sovereign debt, but that would force Western funds to sell their current holdings at substantial losses, to the benefit of Russian buyers.39Vladislav Inozemtsev, “The Physics of Sanctions,” Riddle, March 17, 2021, https://www.ridl.io/en/the-physics-of-sanctions/

Total Russian government debt is small, only 18 percent of GDP at the end of 2020.40“Russia Statistics.” Out of Russia’s total foreign debt of $470 billion, only $66 billion was government debt, of which $21 billion was in foreign currencies and $43.8 billion in ruble-denominated bonds, according to the Central Bank of Russia. Of the remaining foreign debt, $72.5 billion was held by banks (presumably almost exclusively state-owned banks) and $318.5 billion by other corporations.41“External Debt,” Central Bank of Russia, accessed March 23, 2021, https://www.cbr.ru/eng/statistics/macro_itm/svs/

I would like to remind you that what was called Novorossiya (New Russia) back in the tsarist days—Kharkov, Lugansk, Donetsk, Kherson, Nikolayev and Odessa—were not part of Ukraine back then. These territories were given to Ukraine in the 1920s by the Soviet government.”

President Vladimir Putin speaks at 2014’s annual “Direct Line with Vladimir Putin.” Credit: Kremlin.ru

As part of the two last defense bills, the US Congress adopted severe sanctions on suppliers to Nord Stream 2, the Russian gas pipeline from Russia to Germany through the Baltic Sea, which are likely to stop the completion of that pipeline.

The United States and the EU responded to the Russian annexation of Crimea with sanctions against Russian officials, individuals, and enterprises held responsible for the annexation, as well as anybody pursuing business dealings with Crimea. They were joined by several allies, such as Australia, Canada, and Norway. Ideally, these sanctions would have compelled Russia to withdraw from Crimea, but nobody believed that would happen in the near term. Their impact was limited to Crimea, and did not harm the Russian economy. Instead, the more realistic goal of the Western sanctions on Russia’s annexation of Crimea, understood within the Barack Obama administration, was to persistently isolate Crimea economically and politically, and that goal has been accomplished. Crimea’s foreign trade plummeted by 90 percent. Housing prices slumped, while prices of goods and services rose because of supply problems. Annual tourism shrunk, and now comes almost entirely from Russia. The biggest Russian state banks, Sberbank and VTB, have stayed away to avoid the US and EU sanctions. Instead, the already sanctioned Bank Rossiya, owned by friends of Putin from St. Petersburg, and a few minor Russian state banks, notably the Russian National Commercial Bank, operate there.42Anders Åslund, Kremlin Aggression in Ukraine: The Price Tag, Atlantic Council, March 19, 2018, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/kremlin-aggression-in-ukraine-the-price-tag/ The prominent Russian economist Sergey Aleksashenko assesses that Russian financial support to Crimea has so far cost about $5 billion per year.43Sergey Aleksashenko, “Skol’ko stoit Krym? (How Much Does Crimea Cost?),” Ekho Moskvy, March 18, 2021.

On April 17, 2014, Putin held his great Crimean victory speech. In suitably vague, but sufficiently clear, terms, he suggested that he wanted to conquer half of Ukraine: “The essential issue is how to ensure the legitimate rights and interests of ethnic Russians and Russian speakers in the southeast of Ukraine. I would like to remind you that what was called Novorossiya (New Russia) back in the tsarist days—Kharkov, Lugansk, Donetsk, Kherson, Nikolayev and Odessa—were not part of Ukraine back then. These territories were given to Ukraine in the 1920s by the Soviet government. Why? Who knows. They were won by Potyomkin and Catherine the Great in a series of well-known wars. The centre of that territory was Novorossiysk, so the region is called Novorossiya. Russia lost these territories for various reasons, but the people remained.”44“Direct Line with Vladimir Putin,” President of Russia, April 17, 2014, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/20796

But, Putin’s expansionist dreams were not fulfilled. A likely reason was that after Russia’s military offensive started in eastern Ukraine in July 2014, the United States and the EU introduced coordinated, more severe sanctions on Russia. These new sanctions not only targeted people and enterprises, but also three sectors—finance, defense, and oil. This was a major success in terms of deterrence.

In addition to export controls against Russian defense industries adopted by the United States and the EU, in 2017 the US Congress passed a law sanctioning foreign companies and governments that engage in “significant transactions” with the Russian defense sector, though Russia remained the world’s second-largest arms exporter.45“U.S. Remains World’s Top Arms Exporter, With Russia A Distant Second,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, March 11, 2019, https://www.rferl.org/a/us-russia-lead-world-global-arms-exports/29814176.html By blocking Russia’s access to technologies with major military applications and withholding resources from Russia’s military, the West could put more pressure on Russia’s defense industry.46Peter Harrell, “How to Hit Russia Where It Hurts,” Foreign Affairs, January 3, 2019, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/russian-federation/2019-01-03/how-hit-russia-where-it-hurts?utm_medium=email_notifications&utm_source=reg_confirmation&utm_campaign=reg_guestpass

The West also introduced sanctions on three types of oil technology—projects in the Arctic, deep water, and shale fields. In the short term, these sanctions had no impact. Russia’s oil production has remained around its all-time peak, but the West had never sanctioned such a large economy before, and it was therefore cautious not to impose sanctions so severe that could have harmed the West, such as sanctions on the export of oil, as had been used against Iran and Venezuela, because Russia was too big an oil producer, and a global shortage of oil could also have benefited Russia financially through higher oil prices. Yet, the Western oil sanctions are deepening the country’s technological backwardness by prohibiting Western companies from investing in high-end oil-extraction technology projects in Russia or with Russian companies.47Snegovaya, “The Taming of the Shrew.”; Sergey Aleksashenko, Evaluating Western Sanctions on Russia, Atlantic Council, December 6, 2016,https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/evaluating-western-sanctions-on-russia/; Edward Fishman, “Make Russia Sanctions Effective Again,” War on the Rocks, October 23, 2020, https://warontherocks.com/2020/10/make-russia-sanctions-effective-again/; Maria Snegovaya, “Tension at the Top. The Impact of Sanctions on Russia’s Poles of Power,” Center for European Policy Analysis, July 18, 2018,https://www. cepa. org/tension-at-the-top Specifically, Exxon, which had several major investment projects planned together with Rosneft in Russia, was forced to withdraw from all of them, which severely hampers Rosneft abilities. Still, Russia is expected to maintain its current record levels of oil production for about a decade.48Nikita Kapustin and Dmitry Grushevenko, “Evaluation of Long-Term Production Capacity and Prospects of the Oil and Gas Industry of Russian Federation,” E3S Web of Conferences 114, 2019, https://www.e3s-conferences.org/articles/e3sconf/pdf/2019/40/e3sconf_esr2019_02001.pdf; “The Golden Age of Russian Oil Nears an End,” Stratfor, April 16, 2020, https://worldview.stratfor.com/article/golden-age-russian-oil-nears-end-energy-economy-shale-crude

Both the United States and the EU have maintained their sanctions on Russia, and have gradually tightened them. Initially, many argued that the European Union would soon give them up because the sanctions had to be reconfirmed each half year, but that never happened. Several EU countries have not been very enthusiastic about sanctions on Russia—mainly Cyprus, Greece, Hungary, and Italy—but the cost of going against the majority would be substantial for any EU country, and their EU grants and conditions are far more important. Therefore, almost all go along with the majority. The decisive powers are France, Germany, and, so far, they have stayed firm. Under President Donald Trump, the Western coordination of sanctions maintenance was weakened and confused. But, by and large, the sanctions regime has persisted since 2014—and with the new EU-US cooperation under President Joe Biden, it is no longer in question. The tenacity of the Western sanctions on Russia has been much greater than its critics have claimed.

US President Joe Biden delivers remarks on Russia in the East Room at the White House in Washington, U.S., April 15, 2021. REUTERS/Tom Brenner

The impact of the Western sanctions

The most important US sanctions on Russia are those related to Crimea and the Donbas. Have they been effective? The overall impact of the Western sanctions is difficult to assess, because they coincided with a drop in oil prices, which further strained the Russian budget and suppressed the value of the ruble. Most authors have focused on the oil price that fell in 2014 as the main cause of Russia’s economic demise, but one tends to find what one is looking for. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) observed that economic growth “virtually stopped when sanctions and lower oil prices hit in 2014.”49“Russian Federation: Staff Report for the 2015 Article IV Consultation,” International Monetary Fund, August 2019, 50, https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/CR/Issues/2019/08/01/Russian-Federation-2019-Article-IV-Consultation-Press-Release-Staff-Report-48549 A Bank of Finland Institute for Economies in Transition (BOFIT) analysis concluded, “The main factors behind this development were the contraction in demand in Russia and substantial depreciation of the ruble.”50Iikka Korhonen, Heli Simola, and Laura Solanka, “Sanctions, Counter-Sanctions and Russia: Effects on Economy, Trade, and Finance,” Bank of Finland Institute for Economies in Transition 4, 2018

The oil price is only one of three major effects. The other two factors that harmed Russia’s economic growth are financial sanctions and persistently deteriorating governance. The most obvious and easily assessed effect is the reduced inflow of international funds, which is caused by the financial sanctions, and not by the oil price. Another effect is Putin’s kleptocracy, which was also aggravated by the Western sanctions, because any state tends to concentrate state power over enterprises and finance under sanctions, which reduces economic freedom and, thus, growth.

The global financial crisis of 2008–2009 was a negative turning point for the Russian economy, but the situation turned much worse from 2014, when the Western sanctions were imposed.

The financial sanctions limited Russia’s international financing and the effect has been palpable, though poorly recognized. The Obama administration and the EU froze Russian companies’ access to Western financial markets, which also deterred Western companies from investing in Russia. Western financial institutions were banned from issuing loans with maturity periods exceeding thirty days for several of Russia’s biggest banks and companies, ensuring that Western creditors avoided entering into long-term operations with multiple Russian counterparts, while payments were not impeded.

Consequently, until around mid-2016, many Russian banks and companies were unable to raise any funds in the Western capital market, which had a painful impact on Russia’s economy and put pressure on the Russian Central Bank to provide the missing liquidity. US financial sanctions have become particularly important, because the dollar rules global finance. As Edward Fishman has written: “America can wield this power because it possesses…a command of global finance, in which the dollar’s role as the world’s reserve currency and the near-impossibility of conducting cross-border commerce without access to dollars give Washington a weapon it can deploy swiftly, unilaterally, and with devastating impact.”51Edward Fishman, “How to Fix America’s Failing Sanctions Policy,” Lawfare, June 4, 2020, https://www.lawfareblog.com/how-fix-americas-failing-sanctions-policy

An early assumption was that Russia could bypass the Western sanctions by turning to China and the Persian Gulf, but none of the four big Chinese state banks were prepared to offer Russia any credits, because they all had operations in the United States and were painfully aware of the risk of being sanctioned. The same was true of the banks in the Gulf and elsewhere. The US dollar still rules the world.

One can distinguish four direct effects from the Western sanctions: declining foreign debt (that is, forced deleveraging), reduced FDI, strong capital outflows, and extremely cautious government macroeconomic policy. At least the three first are not dependent on the oil price.

The Institute of International Finance (IIF) points to three possible channels of macroeconomic effects caused by sanctions, including

- the fiscal channel, forcing the government to raise taxes or cut spending;

- the balance-of-payments channel, forcing Russia to cut back on imports or to increase its exports in the face of lower capital inflows; and

- the balance-sheet channel, forcing the government or state banks and state-owned enterprises to deleverage.52“Market Interventions: The Case of U.S. Sanctions on Russia,” Institute of International Finance, March 2020, 5.

While these effects reinforce macroeconomic stability, they all reduce economic growth. As the IIF concludes: “Partially as a result of sanctions, GDP growth has remained underwhelming for many years.”53Ibid., 1.

Table 1

Russia’s foreign debt 2014-2020

Overtly, it might sound beneficial that a country reduces its foreign debt. However, it also means that a country abstains from financial resources that could help its economic development, and Russia’s reduction of its foreign debt was not voluntary. The Western financial sanctions introduced in July 2014 forced Russians—both private and public debtors—to pay back their foreign credits and scared most potential creditors away. The impact was substantial. Russia’s total foreign debt shrank from $729 billion at the end of 2013 to $470 billion at the end of 2020; that is a reduction of $259 billion.54“External Debt,” Central Bank of Russia, accessed March 13, 2021, https://www.cbr.ru/eng/statistics/macro_itm/svs/. Since Western sanctions were widely expected from February 2014, when Russia started its occupation of Crimea, the beginning of 2013 is the relevant starting point. Other emerging economies, by contrast, attracted more foreign credits—on average, 30.1 percent more from the end of 2013 to 2020.55“IMF World Economic Outlook Database, October 2020.” If Russia had followed the average emerging economy trend, it would have increased its foreign indebtedness to $949 billion. That is, the Western sanctions compelled Russia to forego international credits of $479 billion, or about one third of its current GDP, which could have gone toward investment and, thus, economic growth.

Foreign investors outside the oil sector were not directly targeted by the Western sanctions, but naturally became worried about investing in Russia. They had to face the risk that the sanctions would be extended, which could happen at any time. Then, they would be exposed to a credit risk. Finally, they might risk their reputation dealing with a severely sanctioned and criminalized country. Moreover, the Russian economy was stagnant in any case, so why take such risks when the upside was so limited? Russia’s inflows of FDI have always been relatively limited, since Russia has persistently benefited from a large current-account surplus, because of its large oil rents. However, between 2014–2019, Russia’s annual net inflows of FDI averaged only 1.39 percent of GDP—a negligible figure—while, in the preceding six-year period, it averaged 3.05 percent of GDP, more than double.56“Foreign Direct Investment, Net Inflows (% of GDP)—Russian Federation,” World Bank, accessed March 13, 2021,https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.KLT.DINV.WD.GD.ZS?locations=RU This implies that Russia missed potential FDI of $169 billion from 2014–2020. Adding this foregone FDI to the foregone foreign credits produces an enormous sum of $648 billion; that is, 34 percent of Russia’s GDP in 2019 (the last normal year before the COVID-19 pandemic).57“Word Economic Outlook. Database, October 2020.” (See Table 1).

The direct effect of the financial sanctions is apparent. From 2010–2013, Russia’s fixed investments, after the global financial crisis, increased by an average of 6.2 percent a year, but during the sanctions years 2014–2020, they declined by an average of 0.5 percent a year.58“Russia Statistics.” According to the IMF, total factor productivity decreased by half a percent a year from 2014–2018 and gross external outflows averaged 2 percent of GDP a year.59“Russian Federation: Staff Report for the 2015 Article IV Consultation.” Total factor productivity (TFP) is a measure of productivity calculated by dividing economy-wide total production by the weighted average of inputs i.e. labor and capital. It represents growth in real output which is in excess of the growth in inputs such as labor and capital. These were effects of Western sanctions, not of the lower oil price.

The sanctions of key Russian businessmen have divided the Russian business community into two cohorts. A limited number of Putin cronies, state-enterprise executives, and oligarchs particularly close to the Kremlin have sold foreign assets, while focusing on real economic activities in Russia and wealth management in offshore havens. Most important Russian businessmen, by contrast, are quietly selling off their assets in Russia at low prices, to the state or Putin’s cronies, while legally transferring their capital to offshore havens and eventually moving to their families who already live abroad (typically in London, France, or Miami). This divide might be straining the relationship between these two elite groups.60Snegovaya, “Tension at the Top.” Contrary to Putin’s claims, the capital accounts show that more capital leaves than comes back to Russia. This capital outflow is accounted for in the foreign debt reduction.

The next question is how the decline in foreign financing impacted GDP. Essentially, foreign financing amounts to investment funds; 34 percent of GDP over seven years is gross foreign financing. It is important to deduct the cost of the foreign loans (interest) and FDI (profit repatriation). The relevant interest rate is Russia’s ten-year Eurobond yield, which has varied greatly and averaged 5.05 percent a year from 2014–2020.61“Russian Government Bond 10Y,” Trading Economics, https://tradingeconomics.com/russia/government-bond-yield Table 1 specifies the interest rate and cost for each year. Because the repatriation and reinvestment of profits vary greatly by year, host country, and financing country, it is difficult to offer a general cost.62“World Investment Report 2019,” United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2019, https://unctad.org/webflyer/world-investment-report-2019 If it were all reinvested in Russia, no deduction would be necessary. The authors arrived at an average addition to GDP from potential increase in foreign debt and FDI of no less than 5.6 percent a year.

Table visualization

Actual Russian foreign debt and omitted foreign debt

Increased FDI and investment based on foreign capital inflow will also increase imports. There is substantial empirical literature on this topic, but its general conclusions are that it depends on many factors: the kind of investment (roads require few imports, while technology needs large imports), distance from the investor, the nature of the inputs required, demand for foreign specialists and managers, etc.63Li-Gan Liu and Edward M. Graham, “The Relationship Between Trade and Foreign Investment: Empirical Results for Taiwan and South Korea, Working Paper 98-7,” Peterson Institute for International Economics, January 1998; Lionel Fontagné, “Foreign Direct Investment and International Trade: Complements or Substitutes?” OECD Science Technology and Industry Working Papers, 1990/03. A rise in investment would lead to a need to import goods, technology, and labor, and a corresponding reduction in the current account. Thus, a second deduction is needed, conditioned on bottlenecks in the Russian economy. Here there are too many hypotheticals and unknowns, compelling the authors to make too many assumptions, so one may just assume a deduction of half of the additional investment. Using that logic, reduce the additional investment by half because of presumed bottlenecks in the Russian economy that have to be eased through imports. Then, the authors arrive at a possible additional annual growth of 2.5–3.0 percent a year during the seven years of sanctions 2014–2020, if the West had not sanctioned Russia in 2014. That is, a total of $350 billion in the course of seven years, or an average of $50 billion a year. The Russian counter-sanctions might not have reduced GDP, but they certainly impacted the standard of living by reducing access to imported foods.

In 2015, the IMF assessed the impact: “Model-based estimates suggest that sanctions and counter-sanctions could initially reduce real GDP by 1 to 1½ percent. Prolonged sanctions could lead to a cumulative output loss over the medium term of up to 9 percent of GDP, as lower capital accumulation and technological transfers weakens already declining productivity growth.”64“Russian Federation: 2015 Article IV Consultation, Country Report no. 15/211,” International Monetary Fund, August 2015, 5, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/scr/2015/cr15211.pdf; “US Sanctions on Russia (R45415—Version: 9),” 46. The authors’ suggestion is that the impact might have been more than twice as large.

In 2019, the IMF noticed, “Output growth averaged 0.5 percent in 2014–18, over 2 percentage points a year slower than originally projected.” Of this, the IMF concluded that only 0.2 percentage points were caused by sanctions, but it attributes 1 percentage points to fiscal factors and 1.2 percentage points to monetary and financial factors.65“Russian Federation: Staff Report for the 2015 Article IV Consultation,” 53.

It all depends on the assumptions. The IMF starts with the pretty arbitrary “originally projected” growth, which was barely 3 percent a year and already presupposed that the economy was depressed. This seems to be the wrong starting point.66Ibid., 50. A much higher potential growth would have been possible if the Russian government had been interested in economic growth, rather than merely in the enrichment of a tiny ruling elite. During these five years, Russia had an average growth of just 0.7 percent a year, while its Western neighbors had an average annual growth of 4–5 percent a year (Hungary 3.9 percent, Poland 4.1 percent, Romania 4.7 percent, and Turkey 5 percent).67“World Economic Outlook Database, October 2020.” Given that all these countries are wealthier than Russia, Russia should have a potential growth on the order of 5–6 percent a year because of the laggard effect, if it had pursued sound economic-growth policies. In reality, however, Russia has not converged with, but has diverged from, its richer neighbors since 2014. Obviously, Western sanctions are a major reason for Russia’s poor performance. In 2020, China, for the first time, overtook Russia in terms of GDP per capita in current US dollars, with $10,582 versus Russia’s $9,972.68Ibid.

Second, the fiscal effects—as well as the monetary and financial factors—are effects of the belt tightening that Russia was compelled to endure because of the Western financial sanctions, and so were the monetary and financial factors. Russian corporations were forced to deleverage because they could no longer raise much international finance, even if the market was not completely closed by the sanctions. In line with the authors’ reasoning, also shared by the IIF, these two effects should be added to the direct effect of sanctions.69“Market Interventions: The Case of U.S. Sanctions on Russia,” 5. This would amount to a total financial sanctions effect of 2.4 percent per year for the years 2014–2018, which is in the authors’ ballpark, but because the meager starting point of “originally projected” growth is too low. As a consequence of the authors’ redefinition of the fiscal, monetary, and financial factors as caused by financial sanctions, their impact becomes twice as large as the effect of the lower oil price.

In an early independent Russian assessment in 2015, Yevsey Gurvich and Ilya Prilepksy assessed that the cumulative impact of sanctions on Russia’s GDP from 2014–2017 would amount to a total of 2.4 percent, while the impact of the oil prices would be three times greater.70Evsey Gurvich and Ilya Prilepskyi, “The Impact of Financial Sanctions on the Russian Economy,” Russian Journal of Economics 1, 4, 2015, 359–385. Iikka Korhonen and co-authors concluded that “the available evidence consistently suggests that between 2014 and 2016 the decline in the price of oil had a much larger negative effect on the Russian economy than sanctions. On the other hand, it is possible that if sanctions on both sides remain in place for an extended period, especially if Russia intensifies its import-substitution policy, Russia’s long-term growth potential will be diminished.”71Korhonen, et al., “Sanctions, Counter-Sanctions and Russia: Effects on Economy, Trade, and Finance.”

Daniel Ahn and Rodney Ludema have carried out a careful microeconomic analysis of the targeted Russia sanctions, but their questions are primarily whether the targeted enterprises suffer and whether the government can shield them. They conclude that “targeted companies are indeed harmed by sanctions,” but that the government bailed them out at considerable cost, which does not provide much information about the total cost of sanctions to the economy. This article does not contain any overall assessment of the macroeconomic impact.72Daniel P. Ahn and Rodney D. Ludema, “The Sword and the Shield: The Economics of Targeted Sanctions,” European Economic Review 130, 2020, 1–21.

Russian authorities discussed many proposed sanctions on the West in public, such as prohibition of flights over Russian territory. But, in the end, they did nothing of significance against the West, only sanctioning a few people who would never get a visa to Russia in any case. Instead, the Kremlin hit the Russian population. In August 2014, Russia introduced “counter-sanctions” against food imports from the countries that had imposed sanctions on Russia. These sanctions raised eyebrows because they hurt Russian consumers, worsening and lessening supplies of many foods and creating higher inflation. The Russian customs destroyed large volumes of food policing this import prohibition.73Andrew E. Kramer, “Russia Seeks Sanctions Tit for Tat,” New York Times, October 8, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/09/business/russian-parliament-moves-closer-to-adopting-law-on-compensation-for-sanctions.html While it did not say so, the Kremlin realized that Russia was the underdog. The counter-sanctions of the Putin government have had minimal impact on Western countries. Daniel Gros and Mattia Di Salvo have assessed that the EU experienced no negative economic effect on the whole.74Daniel Gros and Mattia Di Salvo, “Revisiting Sanctions on Russia and Counter- Sanctions on the EU: The Economic Impact Three Years Later,” Center for European Policy Studies, 2017, https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/epscepswp/12745.htm

Table visualization

Russia’s GDP since 2014

In a contradictory fashion, Russian officials dismiss Western sanctions as ineffective, while they constantly complain about them and ask for them to be lifted.75I. Timofeev, “Санкции против России: взгляд в 2021 г [Sanctions against Russia: A Look at 2021],” Russian International Affairs Council, February 16, 2020, https://russiancouncil.ru/activity/publications/sanktsii-protiv-rossii-vzglyad-v-2021-g/ Tellingly, Russia’s GDP has grown by an average of only 0.3 percent a year since the West imposed financial sanctions on Russia in 2014, and it is not likely to grow significantly again until the Kremlin makes sufficient concessions to the West as to ease the sanctions.76“Russia Statistics.” The IMF assesses that Russia’s GDP has grown by 0.5 percent in total during the seven years 2014–2020. “World Economic Outlook Database, October 2020.”

Since peaking at $2.3 trillion in 2013, Russia’s GDP has fallen by 35 percent to $1.5 trillion in 2020, as the ruble has plummeted with the oil price, but Western sanctions have also depressed the ruble exchange rate.77“Russia Statistics.” The worst effect has been that according to Russia’s newly revised official statistics its real disposable income has fallen by no less than 10.5 percent from 2014 until 2020, which appears an important explanation of Russians’ increasingly negative attitudes toward Putin, other Russian authorities, and the Kremlin’s aggressive foreign policy. If we instead use the prior statistics before revision it would be 13.8 percent. Considering that the Russian government seized direct control of its statistical agency subordinating it to its Ministry of Economy and sacked its prior respected head the unrevised number appears more credible.78Federal’naya sluzhba gosudarstvennyi statistiki (Goskomstat) Rossiya v tsifrakh 2018 g. (Russia in Numbers, 2018, Moscow: Goskomstat, 2019; Goskomstat, Rossiya v tsifrakh 2020 g. (Russia in Numbers, 2020), 37; , Moscow: Goskomstat, 2021, 37; Goskomstat, Informatsiya o sotsial’no-ekonomicheskom polozhenii Rossii, January-February 2021, Moscow: Goskomstat, 2021, 4; Коваленко Анна, “Доходы россиян против рейтинга Путина: население не верит, что «жизнь завтра будет лучше, чем сегодня [Incomes of Russians against Putin’s Rating: the Population Does Not Believe That ‘Life Will Be Better Tomorrow than Today’],” Bell,May 29, 2019, https://thebell.io/dohody-rossiyan-protiv-rejtingov-putina-naselenie-ne-verit-chto-zhizn-zavtra-budet-luchshe-chem-segodnya; Maria Snegovaya, “Guns to Butter: Sociotropic Concerns and Foreign Policy Preferences in Russia,” Post-Soviet Affairs, 36, 3, 2020, 268–279. Daniel Treisman, “Presidential Popularity in a Hybrid Regime: Russia under Yeltsin and Putin,” American Journal of Political Science, 55, 3, 2011, 590–609, https://www.jstor.org/stable/23024939 The obvious conclusion is that Putin does not care about the standard of living of the Russians.

Whenever Putin speaks about the Russian economy, he emphasizes various measures of macroeconomic stability: low inflation, the minimal budget deficit, a public debt of only 18 percent of GDP at the end of 2020, steady current-account surpluses, and international currency reserves of $596 billion at the end of 2020.79“Russia Statistics.” But, he says little about economic growth and avoids the standard of living, presumably aware of how bad the situation really is.

It is good that Russia has established great macroeconomic stability, but Putin seems more interested in maintaining maximum reserves for his own political security than in boosting the standard of living of Russia’s population. Russia desperately needs to raise its low investment ratio and attract entrepreneurship, but the Kremlin is preoccupied with what Putin calls “sovereignty”—that is, sufficient state resources so that Russia can withstand Western sanctions. Russia’s large financial, human, and entrepreneurial assets could be deployed to support Russian economic growth, rather than the maintenance of Putin’s autocracy.

Similarly, investment banks—Western and Russian—praise Russia for its great macroeconomic stability, while they say little about growth or sanctions, because their objective is to hawk Russian bonds.

For unclear reasons, the IMF pursues the same positive advocacy. Its role in Russia seems, at best, dubious. In July 2019, the IMF executive board concluded the Article IV consultation with these initial words: “Russia’s economy continues to show moderate growth, under sound macroeconomic policies but with structural constraints and the effects of sanctions. Output grew by 2.3 percent in 2018, driven by exports and consumption, which was supported by growth in real wages and higher labor demand. Investment registered a moderate increase compared to the previous year.”80“Russian Federation: Staff Report for the 2015 Article IV Consultation,” 5, 50–56. While the United States and its allies are trying to contain the Russian government through financial sanctions, the IMF advises the Russian government how to minimize the effects of these sanctions. Why do the Western allies allow the IMF to do so? By contrast, since 2014 the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development has been prohibited from offering new financing to Russian entities. The West should prohibit the IMF from providing financial advice to the Russian government.

Judgments on whether Western sanctions have been severe and effective vary greatly, along with the perceived aim. The ultimate goal—that Russia withdraws from the Donbas and Crimea—has not been attained, but nobody really thought that was possible. Nor has Russia been deterred from its extensive hybrid warfare with election interference, cyber warfare, assassinations, or usage of forbidden chemical weapons, and the Russian economy has not been truly crippled. Yet, more moderate objectives have been achieved. First of all, the Western sanctions have held together and been maintained. The main argument of this report is that the cost to the Russian economy has been much greater than previously understood. Crimea remains almost completely isolated. The Kremlin abandoned its widely announced attempts to take half of Ukraine after the West imposed substantial sectoral sanctions in July 2014.

The Western financial sanctions are well targeted and work fairly well within the scope of their focus. They also can easily be expanded. The United States and the EU should threaten to do so in a specified fashion unless Russia withdraws from eastern Ukraine.

A policeman walks past a wall sign with the logo of aluminum and power producer En+ Group, attached to the facade of a building in central Moscow, Russia February 13, 2018. En+ Group, the parent of the world’s second-largest aluminum producer Rusal, was heavily sanctioned by the United States before it had to revert course. REUTERS/Sergei Karpukhin

Problems with the sanctions

When the United States and the EU started sanctioning Russia in 2014, many concerns were raised. No such large economy had been sanctioned after World War II.81See, e.g., Hufbauer, et al., Economic Sanctions Reconsidered. Russia’s economy is roughly three times larger than the Iranian economy. The US Treasury worried that too severe sanctions would cause another Lehman Brothers crisis, so it moved cautiously. Russian central-bank reserves and the SWIFT payments system were out of bounds. The US Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC, part of the Treasury Department), with other offices in the Treasury Department, carried out careful due diligence to check what it could do without arousing economic disturbances dangerous to the West. The best way of avoiding dangers was to move step by step. Unlike what many feared, Russia was not too big to be sanctioned.

By and large, this worked well, and OFAC did exemplary due diligence until April 2018 when Oleg Deripaska and six other oligarchs were added to the Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Persons (SDN) list, which prohibits them and their enterprises from operating in US dollars. It resulted in the sanctioning of Deripaska’s many companies, including Rusal, the world’s second-largest aluminium company, and its holding company En+. This time, the Treasury Department had not done proper due diligence, and it overstepped. Nor had it coordinated with, or even informed, its European allies. Rusal produces 6 percent of all aluminum in the world, and its sanctioning caused the aluminum price to skyrocket by 20 percent. Ireland and Sweden hosted Rusal factories, which the US sanctions no longer allowed to work.82Patricia Zengerle and Polina Ivanova, “Rusal Shares Soar, Aluminium Falls as U.S. Lifts Sanctions,” Reuters, January 27, 2019, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-russia-sanctions/rusal-shares-soar-aluminum-falls-as-u-s-lifts-sanctions-idUSKCN1PL0S1 After ten months of negotiations, OFAC eased the sanctions, not very plausibly claiming that Deripaska had given up direct executive control.

Deripaska’s vast GAZ car company in Nizhny Novgorod, Russia, was also fully sanctioned, but it had a joint venture with Volkswagen, which was not allowed to operate with an SDN company. The Russian government suggested that Volkswagen purchase the other half of GAZ, but Volkswagen did not want to invest more in Russia. Nor did it want to abandon its assets because of the US sanctioning. Sensibly, Volkswagen and Germany negotiated and received a lifting of the US sanctions on GAZ to maintain status quo.83Brian O’Toole, The Curious Case of the US Treasury and the GAZ Group, Atlantic Council, July 27, 2020, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/the-curious-case-of-the-us-treasury-and-gaz-group; Personal information to Anders Åslund from the German Ministry for Foreign Affairs, Berlin, May 2019

Ironically, it was not the Russian Federation that was too large to be sanctioned, but Deripaska, which forced the Treasury Department into two embarrassing retreats. The Deripaska debacle has left the Treasury Department with a painful memory. It needs to do its homework better to avoid any repetition. Therefore, OFAC is reluctant to sanction more oligarchs, who might own more than OFAC knows.

A greater concern is that many sanctions are not policed. It is known from the Panama Papers released in April 2016, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) files, and other leaks that sanctioned individuals are ultimate beneficiary owners of assets within US jurisdiction that should be frozen according to adopted sanctions, but little is being done. The US Treasury publishes the total volume of assets it has frozen each year, but the numbers are tiny, and they are not specified. When asked why that is the case, OFAC officials respond that they want to avoid legal cases.84Personal queries from OFAC officials.

The weakest link of the kleptocratic system is that the kleptocrats want to protect their own money with good property rights—and since they allow no property rights at home, they are compelled to keep their savings abroad. Therefore, huge volumes of Russia’s dark money are being held in the West. A conservative assessment of Russian private money being held abroad is $1 trillion.85Filip Novokmet, Thomas Piketty, and Gabriel Zucman. “The From Soviets to Oligarchs: Inequality and Property in Russia, 1905-2016, NBER Working Paper no. 23712,” National Bureau of Economic Research, 2017 About one quarter of this amount is presumably held by Putin and his closest cronies.86Åslund, Russia’s Crony Capitalism, 174. Traditionally, Russian dark money goes through several offshore havens in its laundering, but it predominantly stops in anonymous companies in two major economies that allow anonymous ownership—the United States and the United Kingdom.

Another malpractice the West must abandon is its practice of “golden passports.” Many countries sell residence permits, which eventually can become citizenships for wealthy people, while posing no questions. Cyprus has taken the lead in reversing this unhealthy practice.87Michael Peel and Kerin Hope, “Cyprus to Suspend ‘Golden Passport’ Scheme for Wealth Foreigners,” Financial Times, October 13, 2020, https://www.ft.com/content/e0eedc5a-86af-49cd-a79f-bf68c2ef01ed The Financial Times pointed out that the “US is actually still the leading [citizen by investment] country through its ‘EB-5’ visa. For investing as little as $900,000 for job creation in a distressed part of the US, EB-5 offers a path to permanent residency and citizenship.”88Philip Zelikow, et al., “The Rise of Strategic Corruption: How States Weaponize Graft,” Foreign Affairs, July/August 2020, 107–120.

As Philip Zelikow and his co-authors have argued in Foreign Affairs, corruption has become an instrument of national strategy, and “weaponized corruption has become an important form of political warfare.”89John Dizard, “Pandemic Demand for Golden Visas Shows Globalism Never Really Happened,” Financial Times, March 13–14, 2021.

RELATED CONTENT

How could the sanctions administration be improved?

With realistic expectations of what sanctions can achieve, the combined Western sanctions on Russia had some serious achievements. They have had a negative impact on Russia’s economic situation, influenced the Kremlin’s foreign policy, all while causing the Western economies very little damage. They have forced Russia to retreat from Ukraine, and have arguably stopped the Russian military offensive. But, naturally, they can be improved.90Anders Åslund and Julia Friedlander, “Defending the United States against Russian Dark Money,” Atlantic Council, November 2020; Anders Åslund, “How to Rethink Russia Sanctions,” Hill, February 24, 2021, https://thehill.com/opinion/national-security/540113-how-to-rethink-russia-sanctions

First of all, as Edward Fishman has emphasized, the reason for anybody being sanctioned should be clarified, and the United States should specify both why somebody has been sanctioned and what the subject should do to be delisted. The purpose of sanctions is to help create conditions that allow for their success and, thus, their removal. “U.S. sanctions today are failing for three primary reasons: They are too convoluted, too static and too incremental.”91Fishman, “How to Fix America’s Failing Sanctions Policy.” Fishman argues that US sanctions should be more clear and better communicated.

Another concern is that US sanctions are too static. They tend to persist long after they have ceased to be relevant, and the threat of their escalation is neither concrete nor credible. To reinforce the credibility of sanctions, the United States should clarify what it might do next if Russia does not stop its undesired behavior. For example, the United States could threaten a stepwise escalation of financial sanctions because of Russia’s occupation of eastern Donbas until Russia agrees to withdraw.92Ibid.

Sanctions need to be better coordinated within the government, allies, and US civil society. Fortunately, the restoration of an Office of Sanctions Coordination at the State Department was legislated in the stimulus bill signed into law in December 2020. It recreates such an office, modeled on the former Office of the Coordinator for Sanctions Policy, which was established in 2013 by then-US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and disbanded in 2017 by then-US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson.93Robbie Gramer and Dan de Luce, “State Department Scraps Sanctions Office,” Foreign Policy, October 26, 2017, https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/10/26/state-department-scraps-sanctions-office/

As Daniel Fried and Edward Fishman note: “By enshrining the office in law, Congress is seeking to make it a permanent fixture of the State Department. And by calling for it to be led by an ambassador-level, Senate-confirmed official—who will report directly to the secretary of state—Congress has positioned it well for success.”94Daniel Fried and Edward Fishman, The Rebirth of the State Department’s Office of Sanctions Coordination: Guidelines for Success, Atlantic Council, February 12, 2021, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/the-rebirth-of-the-state-departments-office-of-sanctions-coordination-guidelines-for-success/

The Office of Sanctions Coordination at the State Department needs to coordinate sanctions in all directions. First of all, it should serve as the central node on sanctions policy at the State Department, bringing together perspectives and expertise from all regional and functional bureaus, and giving the State Department one voice on critical sanctions policy issues.

Second, this office should also be in charge of sanctions diplomacy with other countries and international organizations, since sanctions are more effective when levied by many countries in parallel. Unilateral sanctions are often a sign of diplomatic isolation and, thus, weakness. If possible, they should be avoided.

Third, the Office of Sanctions Coordination should facilitate coordination within the US government, and represent the State Department in all interagency meetings that touch upon sanctions policy. In particular, the Office of Sanctions Coordination should work hand in hand with the Treasury Department in general, and OFAC specifically. These two offices should neither duplicate efforts nor compete with one another on sanctions policy.

Fourth, consultation with civil society is important. The Office of Sanctions Coordination should serve as a liaison to business, labor, the NGO community, and Congress.

Finally, Fried and Fishman conclude: “The Office of Sanctions Coordination should work with US allies and partners to facilitate the timely sharing of information that can support sanctions by foreign governments and check efforts at evasion. For ongoing sanctions programs, the office should seek to negotiate regular mechanisms for international information-sharing on sanctions issues. The office should also lead the US government’s efforts to build foreign governments’ capacity to implement and enforce sanctions.”95Ibid.

The first Biden steps on Russia sanctions