Unleashing US-EU defense cooperation

This essay is part of the report “Transatlantic horizons: A collaborative US-EU policy agenda for 2025 and beyond,” which outlines an agenda for common action for the next US administration and European Commission.

The bottom line

Instead of pushing back against European defense efforts as it has done in the past, Washington must fully embrace the steps the European Union (EU) is now taking—including the European Defense Industrial Strategy—and build on nascent structures for US defense cooperation with the EU.

State of play

For decades, the United States has derided and complained about the EU’s lack of defense capabilities. Why doesn’t the EU step up to the plate? Why can’t it handle more of the burden of Europe’s continental defense? Questions regarding the US commitment to Europe’s defense go all the way back to the Eisenhower era: The then-president “lamented that the insufficient defense efforts of US allies in Europe meant that the Europeans were close to ‘making a sucker out of Uncle Sam.’”

The reality, however, is a bit more complicated. The United States has also played an active role in stymieing the EU’s defense capabilities throughout the years, repeatedly warning about the EU implementing protectionist measures, and defense primes worrying about lost contracts. The opposition from many in Washington ranges from concern about the United States eventually being pushed out of Europe’s defense market at best, and the dissolution of the US-European relationship at worst. Take the case of the US reaction to the 1998 St. Malo Summit: British Prime Minister Tony Blair and French President Jacques Chirac signed the St. Malo Declaration, declaring that the EU “must have the capacity for autonomous action, backed up by credible military forces.” US Secretary of State Madeleine Albright responded shortly thereafter at a NATO foreign ministerial with the famous “three D’s” speech, saying there should be no discrimination against, no diminution of, and no duplication of NATO activities. This has been US dogma ever since.

The strategic imperative

Today, this line of reasoning directly undermines the US-European security relationship. The transatlantic partners find themselves in a uniquely dangerous situation: War has returned to Europe, and yet, Europeans are still woefully unprepared to meet the challenge of protecting the continent without a heavy reliance on the United States. Should the worst-case scenario ever materialize, where Europe finds itself in open conflict with Russia and the United States has successfully completed its geographical rebalance to the Indo-Pacific region, Europe would be in trouble. Europe is simply unable to defend itself without the United States as the ultimate backstop. This is not in the interest of the United States or Europe.

For that reason, two things must happen going forward: The EU must build on the momentum it has created over the past two years to continue to lessen its reliance on the United States for its security, and the United States must wholeheartedly support these efforts. This does not translate into a transatlantic defense decoupling, especially if the EU does things right. Nor does this suggest that the United States wouldn’t come to Europe’s aid in the event of a crisis. On the contrary, the United States and the EU will continue to be one another’s closest partners and work together on significant defense projects. But the EU must build its own industrial capacity and allow its defense industry to flourish, ultimately creating a more independent and self-sufficient actor and ally.

Looking ahead

Looking ahead to the next four years, the United States should focus on how US-EU defense cooperation—rather than competition—can make Europe a stronger player. And it should rid itself of the outdated thinking that a strong European backbone is somehow a threat to the transatlantic relationship and NATO.

Early in 2024, the EU released the European Defense Industrial Strategy (EDIS), which aims to strengthen the European defense technological and industrial base (EDTIB). EDIS sets out a vision for the EU’s defense policy through 2035. In theory, the goal is to produce more, quicker. In reality, it means by 2030, intra-EU defense trade should represent at least 35 percent of the value of the EU’s defense market, at least 50 percent of member states’ defense procurement should be procured from the EDTIB (with 60 percent by 2035), and member states should procure at least 40 percent of their defense equipment collaboratively.

Today, for instance, the United States provides around 63 percent of the EU’s defense capabilities, which would decrease if EDIS is done right. So, on the surface, it may appear that the United States would (or should) reflexively dislike this plan because, ultimately, it may result in a decreased US share of the European defense market. And if the past is any indicator, there may eventually be some pushback, although it hasn’t happened yet. One only has to look back at the signing of Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) in 2017 to remember the US overreaction. High-level US officials, including the then-ambassador to the EU, warned of protectionist measures and the inevitable undermining of NATO and the transatlantic relationship writ large. Eventually, the United States signed on as a third-party participant in PESCO projects.

Admittedly, the EU still has a long way to go in realizing these defense procurement goals. A first-ever defense and space commissioner, as proposed by European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen earlier this year and appointed on September 17, will be key as a main point of contact between the United States, NATO, and the EU. Commissioner-Designate Andrius Kubilius (if confirmed) and his team will have their work cut out for them, delicately balancing national interests and power struggles within the twenty-seven-nation bloc.

Policy recommendations

The United States must start by changing its lukewarm approach toward EU defense efforts and put its full-throated support behind EDIS. Luckily, there are already multiple avenues that the two sides can build upon to help facilitate cooperation. In 2022, for example, the United States and the EU created the US-EU Security and Defense Dialogue, which held its second meeting in December 2023. The two sides discussed updates on various defense projects and noted the administrative arrangement between the United States and the European Defense Agency signed earlier in the year. These are admittedly small developments; nonetheless, they are steps in the right direction.

Going forward, this dialogue should be elevated and should take place at least twice a year. At the next meeting, the two sides should come to the table with the goal of creating a vision for EU defense over the next five to ten years, with concrete ways the United States can strengthen, rather than stymie, that vision. The goal should be to find avenues of cooperation and a clear set of areas where the EU must become an autonomous actor. Part of this dialogue should be the United States pushing for the empowerment of the European defense commissioner, and then supporting their efforts once this person is in place.

Then, the United States needs to work within its own political sphere, including closely with the defense industry, to figure out what more autonomy for the EU might mean for future defense contracts. Washington, for example, will likely continue to provide key enablers for European security efforts, and that’s OK. At the same time, some EU countries will have the resources to procure high-end capabilities, whereas smaller countries may look to acquire low-cost, attritable capabilities that are accessible but will still go a long way in moving the ball on readiness in Europe.

Compelling research suggests that funding shortfalls, bureaucratic headaches, power struggles between EU member states, and ongoing debates about whether defense acquisitions should come from outside the EU continue to pose the largest obstacles to deeper European integration. Having a transatlantic aspect to these discussions with the ultimate goal of making the EU more autonomous will be key to both getting projects off the ground and creating a political environment in Europe where there is the actual will to get things done. Another challenge, of course, will be resisting the longstanding tendency to “just buy American” because it’s easier and more available, and creating economies of scale to a point where joint European procurement makes sense. On the US side, the difficulties will be navigating the political minefield of major defense contractors that are worried about losing out on market share, members of Congress who have a personal interest in these contracts, and, ultimately, pushing back against the ossified thinking that has thus far defined this touchy subject. This is certainly a long-term project, but with the support of the United States, Europe could finally be on the right track.

Rachel Rizzo is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center. Her research focuses on European security, NATO, and the transatlantic relationship.

read more essays

The Europe Center promotes leadership, strategies, and analysis to ensure a strong, ambitious, and forward-looking transatlantic relationship.

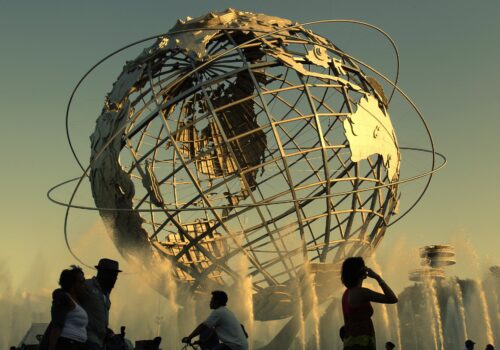

Image: High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Josep Borrell poses at the assault ship-aircraft carrier LHD Juan Carlos I during Milex 23 military drill in Rota, Spain, October 17, 2023. REUTERS/Juan Medina.