The Untapped Potential of the US-Colombia Partnership

Foreword

The United States and Latin America are at a historic moment. As members of the United States Senate, we believe in working closely with our partners to overcome the most difficult political and economic hurdles of our time. In Latin America, the United States has many such strong allies, with Colombia top among them.

For decades, the United States and Colombia have built a solid partnership based on mutual respect, cooperation, and common goals. This alliance has safeguarded the economic, security, and geopolitical interests of our nation, while also advancing Colombia’s path to increased stability, prosperity, and regional leadership. With Colombia’s transformations, the United States stands to reap the benefits of this vital relationship and further work with Colombia to help solve hemispheric challenges.

We must build upon our bilateral successes to ensure sustainable prosperity in the years to come. Colombia faces strong headwinds that require renewed US attention: ensuring the effective implementation of the Colombian peace accords, securing resources to continue providing assistance for Venezuelan migrants and refugees, and mitigating ongoing security threats. By further investing in the US-Colombia relationship, the United States and the US Congress can provide new momentum for the hemisphere.

This report lays out a modernized plan for the bilateral relationship. It builds on the successes of Plan Colombia and provides a roadmap for continued, strengthened, and transformative USColombia engagement. The report follows the work of the Atlantic Council’s US-Colombia Task Force, a group of current and former policymakers, including colleagues in the House of Representatives, business executives, and civil society leaders from both Colombia and the United States. As co-chairs of the Task Force, we are confident the recommendations outlined in the following pages will help advance US interests, contribute to peace and prosperity in Colombia, and promote regional stability.

This is a moment of great promise for the US-Colombia relationship. A more peaceful and prosperous Colombia not only translates to a more secure United States, but also to a more stable Western Hemisphere. We hope the work of this Task Force will help underscore the importance of a deepened and modernized US-Colombia alliance and set the stage for a new era of successful bilateral collaboration.

The multisectoral, bipartisan, bicameral, and bilateral nature of the task force allowed us to develop concrete, fresh, and actionable proposals that will help guide US and Colombian policymakers going forward. We identified three major areas of engagement: economic development and innovation; rule of law, institutional control, counternarcotics; and joint regional leadership. A strengthened US-Colombia partnership along these pillars will pay dividends on US investments far beyond our national borders.

Senator Roy Blunt (R-MO)

Task Force Co-Chair

Senator Ben Cardin (D-MD)

Task Force Co-Chair

Table of Contents

- Overview of Recommendations

- The Need for a New Plan for Colombia

- The Atlantic Council’s US-Colombia Task Force

- Historically Successful Partnership

- A Blueprint for Modernized US-Colombia Partnership

- Building Sustainable Economic Development and Promoting Innovation

- Strengthening Institutions and Rule of Law while Combatting Illicit Drugs

- Recognizing Colombia’s Leadership in the Context of the Venezuelan Regional Crisis

- The Takeaways

- Task Force Co-Chairs and Members

- Acknowledgments

Executive Summary

Colombia is one of the United States’s closest allies in the Western Hemisphere. For decades, both nations consolidated a mutually beneficial partnership that successfully safeguarded US and Colombian national security interests. Today, with increased interconnectedness, both nations’ security, economic, and geopolitical interests are more intertwined than ever before.

Colombia’s transition into a more peaceful and prosperous democracy makes it imperative that the United States and Colombia seize this moment to expand and deepen the partnership. The findings presented in the following pages require urgent attention. Although Colombia is a different country than it was two decades ago, new challenges with peace accord implementation and Colombia’s role as the top receiving country of Venezuelan migrants and refugees make finding new ways to work together crucial — Colombia’s success is the United States’ success.

This report provides a blueprint for a modernized US-Colombia strategic partnership. It is the product of a nonpartisan, bicameral, multisector, and bicountry task force launched in March 2019 by the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center. Composed of high-level business executives, current and former policymakers, and civil society leaders from Colombia and the United States, the task force offers concrete, actionable, and fresh proposals on how to strengthen the bilateral relationship. The ideas are intended to provide guidance to both the Colombian and US administrations, the US Congress, and the respective business communities on opportunities to maximize the full potential of the US-Colombia relationship. Task force recommendations are divided into three categories: sustainable economic development; rule of law, rural development, and counternarcotics efforts; and joint leadership around the Venezuela regional crisis.

Tapping the full potential of the US-Colombia partnership must include the promotion of economic development. A healthy Colombian economy directly serves US national security interests as it contributes to rural development, which is critical to undermine the drug trade and other illicit economic activities as well as illegal armed actors. Fully implementing all aspects of the US-Colombia Trade Promotion Agreement (TPA) and endorsing the double taxation agreement will lead to deepened bilateral trade and investment.

This report serves as a blueprint for addressing the challenges and responses that would strengthen US national security and regional stability.

U.S. President Donald Trump and first lady Melania Trump stand with Colombian President Ivan Duque and his wife Maria Juliana Ruiz after their arrival at the White House in Washington, U.S., February 13, 2019. REUTERS/Carlos Barria

The task force identified Colombia’s taxation system and high levels of informality as two major barriers to economic development. The partnership can include collaboration to modernize Colombia’s taxation agency and reduce informality. Further digitalizing Colombia’s economy, simplifying processes for firm creation and closure, improving access to credit and other business services, setting corporate taxes at levels similar to those of other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, and making labor regulations more flexible, will all help to incentivize the formal (or licit) economy and undermine informality. Advances in innovation, science, technology, and education are also crucial to achieve the economic development needed to combat illegal armed groups and reduce coca production and cocaine trafficking.

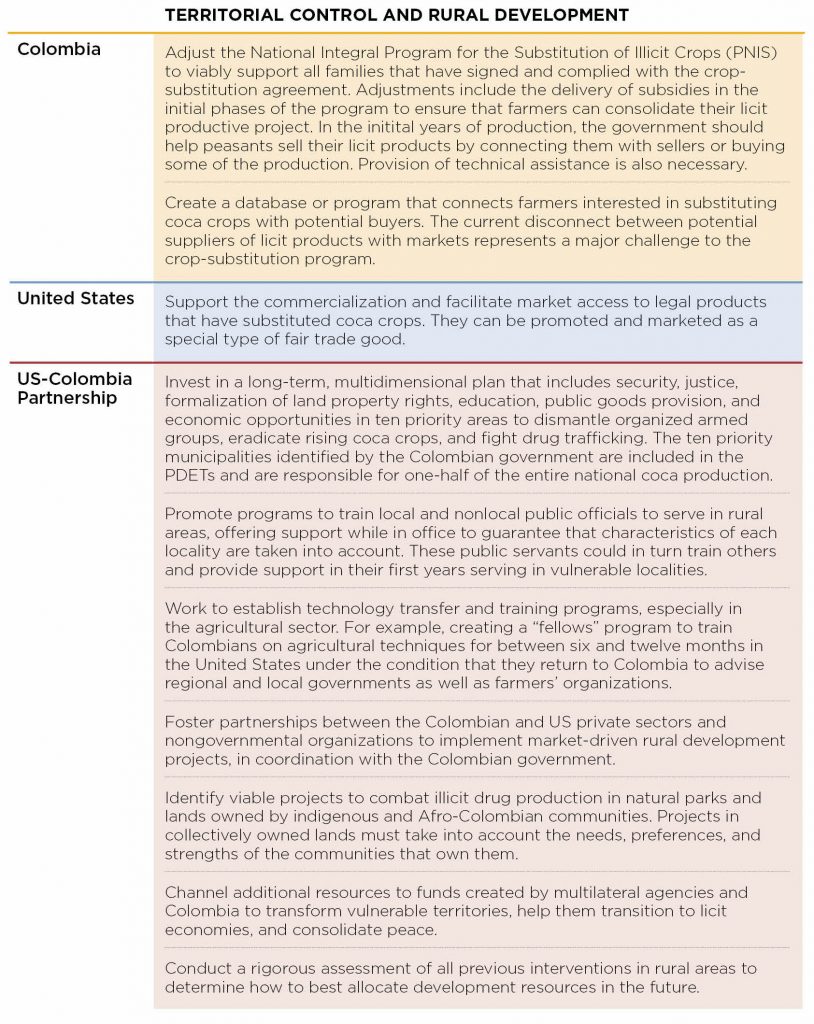

Advancing shared US and Colombian security interests requires the stabilization of territories where coca crops are cultivated, illicit armed actors operate, and local populations face high levels of violence and poverty. Critical to regaining control of rural areas is implementation of the Peace Agreement with the FARC. The task force recognizes the need for a long-term, adequately resourced intervention strategy that includes security, justice, formalization of land property rights, education, public goods provision, and economic opportunities in priority areas to dismantle organized armed groups, eradicate rising coca crops, and fight drug trafficking. If a successful, multidimensional intervention plan is implemented in ten municipalities, the US-Colombia partnership will disrupt the conditions that favor illegality in territories responsible for almost half the entire national coca production. Colombia and the United States should promote partnerships between both countries’ private sector and civil society to develop market-driven, large-scale and holistic rural development projects in coordination with the Colombian government.

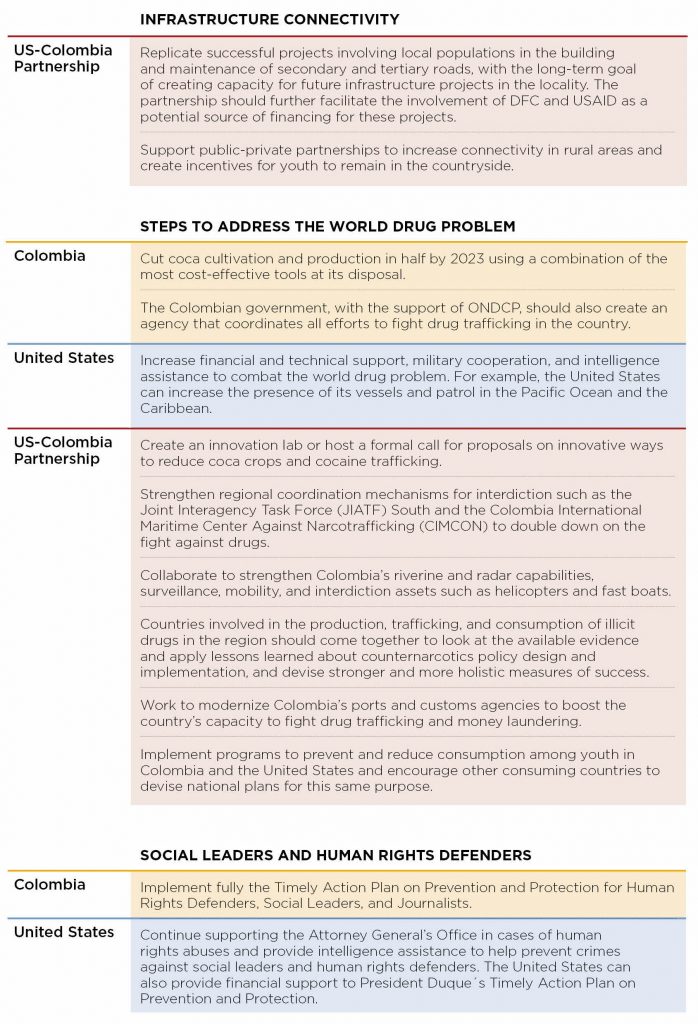

Safeguarding US and Colombian security interests also requires enhancing rural connectivity in Colombia, addressing the world drug problem, and protecting Colombian social leaders and human rights defenders. Rural infrastructure stands as a prerequisite to rural economic growth and the success of crop substitution programs. Unless farmers can get their legal products to market, no eradication effort will prove sustainable in the long run. Colombia and the United States can work together to replicate successful projects involving local populations in the building and maintenance of secondary and tertiary roads, with the long-term goal of creating capacity for future infrastructure projects in the locality. To address the world drug problem in an integral way, the US-Colombia partnership should not only aim to reduce coca crops in the short run but also continue to target other stages of the drug market, including cocaine production, trafficking, and consumption.

The United States and Colombia share a firm commitment to human rights and should therefore continue to collaborate to end the rising levels of violence against social leaders and human rights defenders in Colombia. The United States can support Colombia’s current efforts by providing financial assistance for President Duque’s Timely Action Plan on Prevention and Protection for Human Rights Defenders, Social Leaders, and Journalists (PAO). Colombia, in turn, should develop a progress report for the PAO with clear follow-up mechanisms that involves civil society organizations in the process.

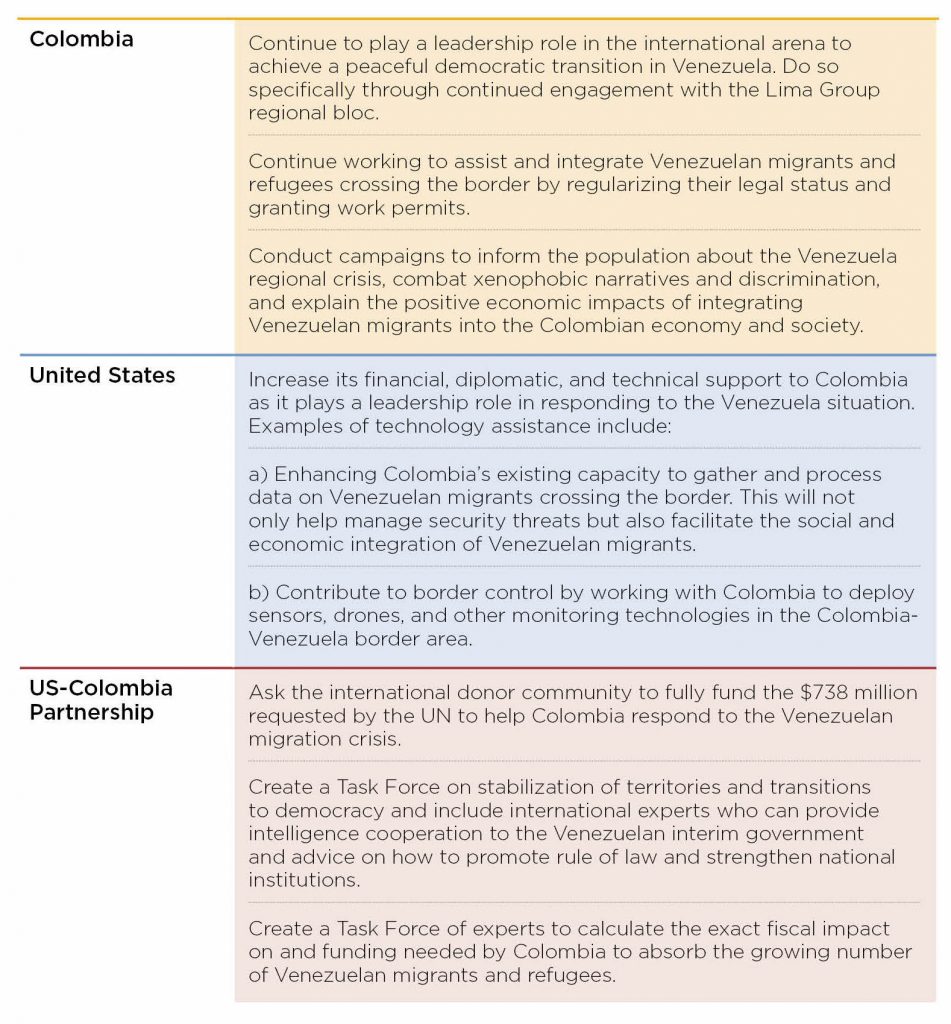

The political, economic, and humanitarian crisis in Venezuela is a threat to regional stability. Colombia has demonstrated commendable solidarity in receiving over 1.4 million Venezuelan migrants and refugees – a number that will continue to grow in the coming months and years. The United States should increase its financial, diplomatic, and technical support to Colombia as it plays a leadership role in addressing the crisis. If current international support does not increase, Colombia runs the risk of spiraling into economic stagnation, violence, criminality, illicit economies, and decayed governance. This will not only harm US national security and geopolitical interests but will lead to major economic losses to previous and current US investment in Colombia. The United States can further support its ally by enhancing the Colombian government’s capacity to gather and process data on Venezuelan migrants and refugees entering the country and by contributing to border control through monitoring technologies. The US-Colombia partnership can also create a task force to calculate the fiscal impact of the crisis to Colombia to understand the exact level of funding that will be required to absorb the growing number of Venezuelans. In addition, the partnership can support the efforts of the Venezuelan interim government by convening a group of experts on stabilization of territories and transitions to democracy that can provide it with intelligence cooperation and guidance on the promotion of rule of law and strengthening of national institutions.

The US-Colombia partnership is one of the greatest US foreign policy successes over the last two decades. Dedicated, sustained, bipartisan commitment to achieving common goals, once thought to be out of reach, was possible due to US congressional leadership and a commitment to work across US administrations. At the same time, successive Colombian governments showed themselves to be critical partners for the United States—both in-country and beyond its borders. But we cannot rest on our laurels. New domestic and regional paradigms make this moment imperative to define how our relationship can and should be taken to the next level.

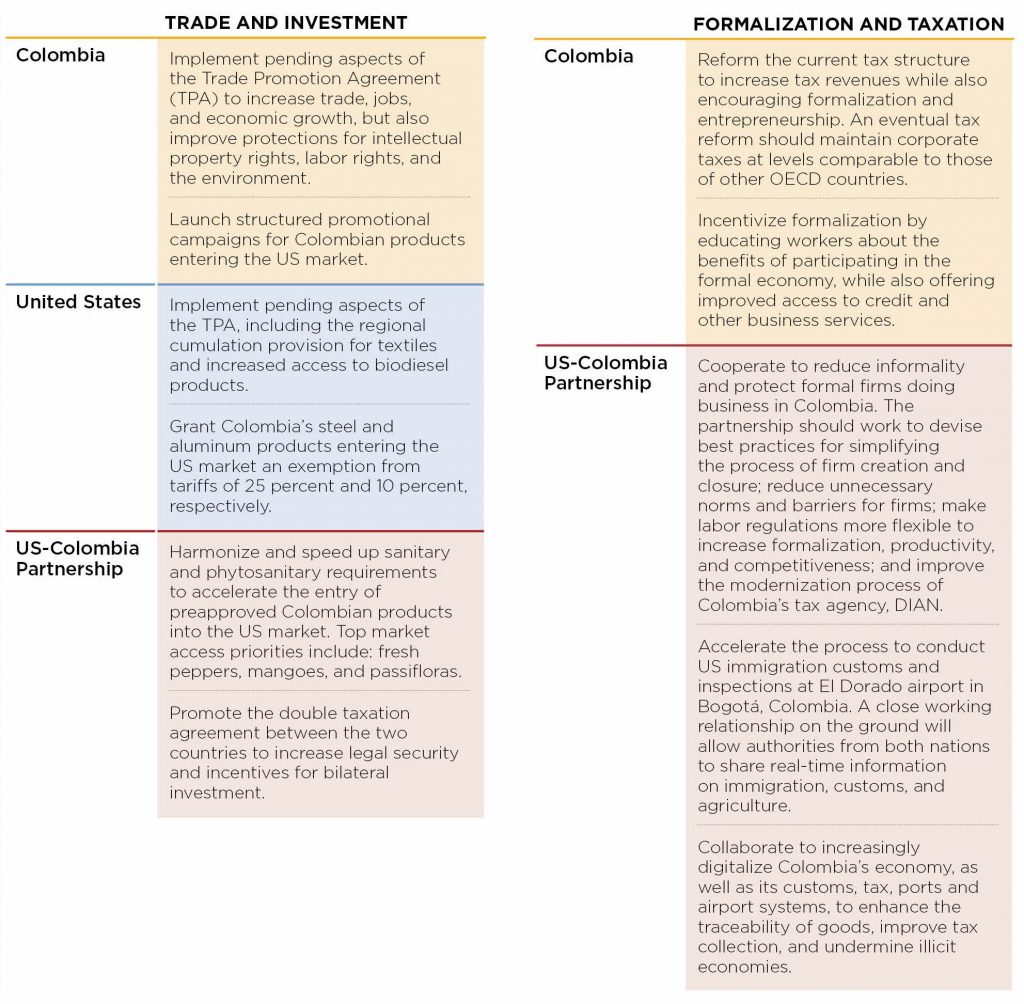

Overview of Recommendations

Sustainable Economic Development and Innovation

Institutions, Rule of Law, and Illicit Drugs

Colombia’s Leadership In the Context of the Venezuela Crisis

The Need for a New Plan for Colombia

Colombia is one of the United States’ strongest, most reliable allies in the Western Hemisphere. It collaborates with the United States in fighting international drug trafficking and transnational organized crime, as well as in promoting democracy, rule of law, and economic prosperity in the region. At the United Nations (UN), among other things, Colombia supports US diplomatic efforts on priorities such as North Korea, Syria, Iran, and Ukraine. It also contributes security expertise in Central America, Afghanistan, and a number of countries in Africa. Colombia is NATO’s only global partner in Latin America, one of the two Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) member countries in South America, and a regional leader in facing the crisis in Venezuela. Here, its generous response to the massive influx of Venezuelan migrants and refugees should be viewed as a model for countries around the world.

With the US-Colombia Trade Promotion Agreement (TPA), the opportunities for mutually beneficial trade are enormous. The United States is Colombia’s largest trading partner and Colombia is the United States’ third-largest export market in Latin America behind Mexico and Brazil.1Embassy of Colombia, “Colombia and the United States: A Successful Trade Alliance,” https://www.colombiaemb.org/TradeAlliance. Today, with increasing hemispheric challenges, the US-Colombia strategic partnership is more important than ever. By continuing to invest in the already strong bilateral relationship, both countries stand to benefit in the short, medium, and long term.

Colombia is pivotal in addressing Venezuela’s unprecedented political and economic crisis, which has led to the largest mass migration in Latin American history. With 1.4 million Venezuelan migrants in its territory as of June 2019, Colombia is the primary destination for Venezuelans.2“Venezolanos en Colombia,” Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores – Gobierno de Colombia, August 1, 2019, http://migracioncolombia.gov.co/index.php/es/prensa/infografias/infografias-2019/12565-infografia-venezolanos-en-colombia. President Iván Duque has adopted a policy of complete solidarity toward Venezuelan migrants,3El Consejo Nacional de Política Económica y Social (CONPES), “Estrategia Para La Atención de la Migración desde Venezuela,” November 23, 2018, https://colaboracion.dnp.gov.co/CDT/Conpes/Económicos/3950.pdf. providing medical care, housing and public education, among other services. According to the World Bank, the estimated economic cost for Colombia in 2018, not including infrastructure and facilities, reached 0.4 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), or the equivalent of $1.5 billion.4The World Bank, “US$31.5 Million to Help Improve Services for Migrants from Venezuela and Host Communities in Colombia,” April 12, 2019, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2019/04/12/us315-million-to-help-improve-services-for-migrants-from-venezuela-and-host-communities-in-colombia.

Today, with increasing hemispheric challenges, the US-Colombia strategic partnership is more important than ever.

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo (right) and Colombian Foreign Minister Carlos Holmes Trujillo speak with reporters before their meeting at the US State Department in Washington in 2019. Deepened US-Colombia collaboration in areas of economic development, security, and regional stability will further advance mutual interests. (Reuters/Yuri Gripas)

Colombia has also sought to confront increased illegal activity in Venezuela, including illegal mining, the arms and drug trade, and human trafficking, as well as the smuggling of goods and money laundering. Here, a contradiction exists around the role of China. At the same time that China is increasing its economic ties with Latin America—and while Colombia’s exports to China increased 83 percent in 2018 compared with 2017—it continues to support the Maduro regime, helping to maintain a criminal enterprise in Venezuela that directly threatens Colombia’s interests. As the presence of guerrilla groups, drug cartels, and other transnational criminal organizations in Venezuela5“ELN in Venezuela,” InSight Crime, March 11, 2019, https://www.insightcrime.org/venezuela-organized-crime-news/eln-in-venezuela/. creates new security challenges for the region, Colombia’s role in maintaining regional stability becomes more vital than ever. Eventual reconstruction efforts in Venezuela will also require enormous Colombian support.

In addition to its partnership with the United States in the region, Colombia plays a unique role in tackling the world drug problem, as also stated in the Global Call to Action by President Donald Trump at the 2018 United Nations General Assembly. Colombia has the most to lose if the fight against drugs is unsuccessful, and it has thus advanced a full-on strategy to disrupt the cocaine trade. The United States has been a crucial ally in this quest. Since Plan Colombia was announced in 1999, the United States has provided more than $11 billion6Congressional Research Service, “Colombia: Background and U.S. Relations,” February 8, 2019, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R43813.pdf. to aid the Colombian government in strengthening state capacity and institutions, decreasing coca crops, and fighting the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and other illegal groups that profited from drug trafficking. Colombia has contributed more than 95 percent of the total investment in Plan Colombia.7Dirección de Justicia, Seguridad y Gobierno (DJSG) and Dirección de Seguimiento y Evaluación de Políticas Públicas (DSEPP), “Plan Colombia: Balance de los 15 años,” Departamento Nacional de Planeación – Government of Colombia, 2016, https://sinergia.dnp.gov.co/Documentospercent20depercent20Interes/PLAN_COLOMBIA_Boletin_180216.pdf.

Between 2001 and 2016, the country destroyed 37,504 illegal laboratories, seized an average of 181,201 kilograms of cocaine each year, and reduced the area containing coca crops by half in the first six years.8United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), “Colombia – Monitoreo de territorios afectados por cultivos ilícitos 2016,” July 2017, https://www.unodc.org/documents/colombia/2017/julio/CENSO_2017_WEB_baja.pdf. Colombia has also made enormous sacrifices in terms of lives lost: between 2009 and 2018, 126 members of the state security forces as well as civilians died in eradication missions and 664 were wounded.9Juan Carlos Garzón Vergara, Juan David Gelvez F., and Ángela María Silva Aparicio, “Los costos humanos de la erradicación forzada ¿es el glifosato la solución?,” Fundación Ideas Para la Paz, March 7, 2019, http://www.ideaspaz.org/publications/posts/1734. Overall, during the first fifteen years of Plan Colombia, about six million people—including members of the state forces, combatants of illegal groups, and, mostly, civilians—were victims of a violent event such as forced displacement, homicide, or kidnapping.10Red Nacional de Información, “Inicio,” Unidad Victimas – Government of Colombia, August 1, 2019, https://cifras.unidadvictimas.gov.co/. By 2017, and after decades of enormous efforts, successive governments in Colombia had advanced in dismantling the most significant drug cartels, reached agreements to demobilize several paramilitary forces, and started the implementation of the Peace Accords with the FARC. In 2017, the country achieved the lowest homicide rate in its past forty-two years.11“Homicidios en Colombia: La tasa más baja en los últimos 42 años se dio en 2017,” El Espectador, January 21, 2018, https://www.elespectador.com/noticias/judicial/homicidios-en-colombia-la-tasa-mas-baja-en-los-ultimos-42-anos-se-dio-en-2017-articulo-734526.

In 2019, the UN Security Council, following its mission visit to Colombia in July, called Colombia’s ability to negotiate a peace agreement in 2016 “an example for others around the world.”12United Nations Security Council, “Security Council Press Statement on Colombia,” July 23, 2019, https://www.un.org/press/en/2019/sc13896.doc.htm. The Council also “welcomed Government efforts to advance the reintegration of former FARC-EP members and strengthen rural development” and stressed the importance of “implementing the peace agreement as an interlocking set of commitments.”13United Nations Security Council, “Security Council Press Statement on Colombia.”

However, several challenges to Colombia’s national security and democracy as well as the rights of its citizens still remain. These challenges are partially explained by the capacity of existing illegal armed groups and criminal organizations to adapt and take advantage of conditions that favor their growth—i.e., insufficient institutional presence, limited economic opportunities, and the availability of illegal funding sources. After the demobilization of the FARC, several armed groups competed for territorial control in areas where the guerrilla group used to operate. A vacuum had been left for them to exploit and profit from illicit economies such as drug trafficking, illegal mining, and extortion.14El Tiempo, “Estos son los grupos armados que azotan a varios departamentos,” July 23, 2019, https://www.eltiempo.com/colombia/otras-ciudades/regiones-del-pais-afectadas-por-grupos-armados-en-colombia-391642.

The rights of vulnerable populations in areas where the state is fragile therefore remain unprotected. According to Colombia’s Victims Unit, more than 360,000 people were internally displaced between January 2016 and July 2019.15Red Nacional de Información, “Desplazamiento – Personas: Registro Unico de Victimas,” Unidad Victimas – Government of Colombia, August 1, 2019, https://cifras.unidadvictimas.gov.co/Home/Desplazamiento. The situation of social leaders is particularly critical—more than 300 have been killed since 2016.16José David Rodríguez Gómez, “Más de 317 líderes sociales han sido asesinados en el último año: Medicina Legal,” RCN Radio, May 15, 2019, https://www.rcnradio.com/colombia/mas-de-317-lideres-sociales-han-sido-asesinados-en-el-ultimo-ano-medicina-legal. Corruption, which President Duque has identified as a top priority (and recently submitted legislation to counter it), has facilitated criminal activities and undermines the legitimacy of the Colombian state. At the same time, while there has been progress in the implementation of the Peace Accords, there is still a long way to go to achieve the accords’ stated goals and commitments. Additionally, instability in Venezuela and the meddling of Russia, in particular, contributes to new security challenges.

Deepening Colombia’s alliances with the United States in security and economic issues is of paramount importance for both countries to achieve their common goals.

These problems do not only affect Colombia: They also directly compromise US goals. A new US-Colombia partnership can better address the structural conditions that favor illicit activities, thus reducing the flow of cocaine to the United States. The two countries can also deepen cooperation to help governments in Central America, Mexico, and South America confront transnational criminal organizations, drawing on Colombia’s experience as a leader in addressing regional security issues.

Deepening Colombia’s alliances with the United States in security and economic issues is of paramount importance for both countries to achieve their common goals. The terms of this partnership must originate with a long-term plan to effectively transform the conditions that currently favor illegality and enable the production and trafficking of cocaine but then move to a long-term vision that fully maximizes the relationship and Colombia’s regional role. This commitment to an even more robust, long-term strategic alliance will set Colombia on a path for sustainable growth and ensure that both countries’ interests are mutually reinforcing.

This report outlines the main areas for US-Colombia cooperation that the Atlantic Council’s US-Colombia Task Force identified to advance US and Colombia interests while fostering a more secure and prosperous Western Hemisphere.

The Atlantic Council’s US-Colombia Task Force

Colombia is in a period of momentous transition. It is rapidly consolidating its role as a key player in Latin America and an indispensable partner for the United States on many fronts. Simultaneously, the United States has become an important source of political and economic support for Colombia, making it imperative to deepen ties between the two countries at this critical time in Colombia’s history. Colombia must not only ensure that peace is in fact achieved, but also grapple with the external and internal challenges that arise from the worsening of the crisis in Venezuela. US economic, humanitarian, and security assistance to Colombia, as well as continued bipartisan support, is thus vital for the long-term interests of Colombia and the United States.

The Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center launched its US-Colombia Task Force to create the foundation for a new plan of action vis-à-vis the US-Colombia economic and diplomatic relationship. This distinguished group built on the recommendations of the Atlantic Council’s 2017 Colombia Task Force, which provided the Trump administration with a blueprint for US engagement with Colombia. This refocused and expanded US-Colombia Task Force provides a roadmap for the Duque administration, the Trump administration, and the US Congress on how to deepen and expand the relationship along three pillars: economic development; strengthening institutions and rule of law, promoting rural development, and tackling the world drug problem; and Colombia’s leadership in the context of the Venezuela regional crisis.

The task force is co-chaired by Senator Roy Blunt (R-Missouri) and Senator Ben Cardin (D-Maryland). Senator Blunt serves on the Senate Appropriations Committee and Senator Cardin is a senior member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. In addition to bipartisan leadership, members include a bipartisan grouping from the US House of Representatives: Congressman Bradley Byrne (R-Alabama); Congressman Ruben Gallego (D-Arizona); Congressman Gregory Meeks (D-New York); and Congressman Francis Rooney (R-Florida). The task force also includes former policymakers from and leaders in business and civil society in both the United States and Colombia, who provide expert insight to help guide the leaders of both countries in advancing the next chapter of the US-Colombia relationship. The task force is a truly nonpartisan, bicameral, binational working group with a wide reach and the foundation to create impact for years to come.

Historically Successful Partnership

COLOMBIA AS ONE OF THE UNITED STATES’ CLOSEST ALLIES

The United States and Colombia have consolidated a close and mutually beneficial partnership over the past decades. Plan Colombia, announced in 1999 and sustained by US leaders of both political parties, laid the foundation for a strategic alliance that has widened to include sustainable development, trade and investment, hemispheric security, human rights, and other areas of cooperation. Plan Colombia has been one of the United States’ most successful foreign policy initiatives in the past 20 years. Its success is visible today in Colombia’s positive transformations and the safeguarding of vital US interests. As former National Security Advisor Stephen J. Hadley, who served under President George W. Bush and is now executive vice chair of the Atlantic Council, said, “Plan Colombia is an example of a visionary, bipartisan strategic framework that has supported the Colombian people and government as they have transformed Colombia into a peaceful democracy.”17Atlantic Council, “A Roadmap for US Engagement with Colombia,” May 2017, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/images/publications/A_Roadmap_for_US_Engagement_with_Colombia_web_0517.pdf.

Although Colombian taxpayer funds financed almost 95 percent of the total investment in Plan Colombia, US political leadership, military and police training, and technology assistance were crucial to the success of this bipartisan foreign policy initiative. US investment in Plan Colombia totals $11 billion, with $10 billion provided between 2000 and 2016—a number that represents less than 2 percent of the cost of the Iraq war over the same period.18Congressional Research Service, “The Cost of Iraq, Afghanistan, and Other Global War on Terror Operations Since 9/11” (2014), https://fas.org/sgp/ crs/natsec/RL33110.pdf. A strong return on US investment is evident. In those same years, Colombia significantly strengthened its institutional capacity and made notable progress combating drug trafficking, fighting illegal armed groups, and securing government control of territories. Additionally, Colombia’s liberalized economy quadrupled in size, poverty and homicides fell by more than 50 percent, and kidnappings were reduced by 90 percent.19Miguel Silva, “Path to Peace and Prosperity: The Colombian Miracle,” Atlantic Council, 2015, http:// publications.atlanticcouncil.org/colombia-miracle/; United States Senate, “S.Res.368 – A resolution supporting efforts by the Government of Colombia to pursue peace and the end of the country’s enduring internal armed conflict and recognizing United States support for Colombia at the 15th anniversary of Plan Colombia,” 2016, https://www. congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/senateresolution/368/text. With its improved security situation and strengthened democratic institutions, Colombia transitioned from being an aid recipient to a strategic ally of the United States and an exporter of security and political leadership in the region.

The successor strategy to Plan Colombia, Peace Colombia, was announced by President Barack Obama in February 2016. This multiyear initiative sought to scale up vital US support to help Colombia “win the peace,” in the event of a peace agreement with the FARC.20The White House, “Remarks by President Obama and President Santos of Colombia at Plan Colombia Reception,” February 4, 2016, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2016/02/05/remarks-president-obama-and-president-santos-colombia-plan-colombia; The White House, “Fact Sheet: Peace Colombia — A New Era of Partnership between the United States and Colombia,” February 4, 2016, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2016/02/04/fact-sheet-peace-colombia-new-era-partnership-between-united-states-and. Less than five months later, a peace agreement was signed. Peace Colombia was designed to consolidate Plan Colombia’s security gains; advance counternarcotics efforts; reintegrate former combatants into society; expand state presence and institutions, especially in territories most affected by violence; provide titles and access to land for poor farmers; and promote justice and economic opportunities for Colombians.21The White House, “Fact Sheet: Peace Colombia — A New Era of Partnership between the United States and Colombia.” As with Plan Colombia, Colombian taxpayers were expected to fund close to 90 percent of the total budget for the initiative. In fiscal year (FY) 2018, the US Congress approved an omnibus appropriations measure funding Peace Colombia programs at $391 million.22Congressional Research Service, “Colombia: Background and U.S. Relations.” Although President Trump’s FY 2019 budget request for Colombia was $265 million (a 32 percent reduction from the $391 million appropriated by congress in FY 2018), the 2019 Consolidated Appropriations Act provided Colombia “no less than” $418 million in funding.23Peter J. Meyer, and Edward Y. Gracia, “U.S. Foreign Assistance to Latin America and the Caribbean: FY2019 Appropriations,” Congressional Research Service, March 1, 2019, https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R45547.pdf. This additional assistance has a focus on drug eradication and interdiction efforts as well as rural security. For FY 2020, the administration requested $344 million in funding for Colombia.24Congressional Budget Justification, “Department of State, Foreign Operations, And Related Programs: Fiscal Year 2020,” May 22, 2019, https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Supplementary-Tables-%E2%80%93-Foreign-Operations.pdf. Continued and deepened US assistance to Colombia is more important than ever as Colombia receives a growing number of Venezuelan migrants and refugees and continues to work toward the implementation of the 2016 peace agreement. A stable and prosperous Colombia will safeguard US national security, economic, and geopolitical interests in the region, generating a strong return on US investment.

COLOMBIA AS A NATO PARTNER AND PARTICIPANT IN PEACEKEEPING OPERATIONS

Colombia’s cooperation with NATO started in 2013. Four years later, the Individual Partnership and Cooperation Program (IPCP) made Colombia NATO’s first and only global partner in Latin America and the ninth in the world, alongside Afghanistan, Australia, Iraq, Japan, South Korea, Mongolia, New Zealand, and Pakistan. As a NATO partner, Colombia has access to and engages in various organization activities ranging from trainings and education to military exercises.

Given the challenges it has faced over the past five decades as well as its leading role in security and defense cooperation in Central and South America, Colombia has significant contributions to make to NATO and the global community. For example, the country recently started participating in the Science for Peace and Security Program, and was invited to a research workshop in Denmark this year, focusing on counterterrorism lessons from maritime piracy and narcotic interdiction. In addition, Colombia’s International Demining Centre (CIDES) joined the network of NATO Partnership Training and Education Centers in March 2019. CIDES will contribute to the education and training of personnel from NATO nations and partners in the crucial areas of humanitarian procedures and military demining. Colombia and NATO plan to develop common approaches in supporting peace and security efforts. Under this same program, Colombia and NATO are working on the implementation of United Nations Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 1325 on Women, Peace and Security, as well as protecting children and civilians in armed conflict.

At the same time, the IPCP will benefit Colombia, allowing it to access cooperation and training programs. The agreement is expected to improve the country’s humanitarian operations, rescue missions, crisis management, and security collaboration for civil emergencies, as well as inform its fight against terrorism, cybersecurity, and organized crime. It also is expected to help export Colombia’s experience, an added value for the Alliance. The program will reinforce both political dialogue and interoperability with the armed forces of partner countries. The US Congress can further support Colombia’s role by advocating for Colombia to become a non-NATO ally.

Colombia also is advancing its participation in UN peacekeeping missions. The Colombian Armed Forces are training service members who will join UN forces to help countries in conflict achieve peace. Trainees will take courses on human rights, international humanitarian law, and UN Peacekeeping Operations commands and doctrine, while at the same time learning about the culture of the countries of placement.25Myriam Ortega, “Colombia Boosts Peace Missions Participation,” Diálogo, February 12, 2018, https://dialogo-americas.com/en/articles/colombia-boosts-peace-missions-participation.

COLOMBIA AS A HUB FOR REGIONAL SECURITY

Colombia is a strategic partner for the United States and its success in combating organized crime has been a significant mutual achievement. Colombia’s experience in that fight and the lessons learned from Plan Colombia have given the country considerable security expertise. Today, Colombia is training public servants from numerous countries on security-related issues. Between 2010 and 2018, over 46,000 individuals from eighty-one countries received training by Colombian public officials on the fight against drugs, the prevention and control of crime, the strengthening of the military and police, and citizen security and organizational development. About 60 percent of those trained were in Central America under the Triangular Cooperation Plan between Colombia and Canada (2013), and the Cooperation Plan between Colombia and the United States to strengthen Central America and the Caribbean (USCAP).

In 2012, the United States and Colombia signed the Regional Security Joint Action Plan. Since then, personnel from the military forces, police, and similar institutions of beneficiary countries have been trained. For 2020, Argentina, Ecuador, and Paraguay are projected to become beneficiary countries of the program. The United States and Colombia should expand their shared security portfolio in international hot spots where Colombia can play a pivotal role. This would advance US interests globally, while also reducing costs to the United States and minimizing cultural and language barriers.

In the last twenty years, Colombia’s National Police has also increased its cooperation with various countries in the region as well as with Interpol, the international criminal police agency that the country joined in 1954. Colombia has taken a leading role in the creation and management of the American Police Community, or Ameripol, since 2007, an organization that integrates thirty-three police forces of Latin America and the Caribbean. Between 2010 and 2012, Colombia supported more than sixty “outsourcing” activities in security, benefiting more than 220 institutions and fifty national and local partners. With support from the United States, Colombia trained more than 10,000 officers in forensic investigation and special operations between 2009 and 2013.

In that same period, Colombia trained almost 22,000 military and police personnel from various countries.26Diego Felipe Vera, “Cooperación Internacional y Seguridad: el Caso Colombiano,” in Memorias del Seminario Académico “Prospectivas en seguridad y defensa en Colombia,” ed. Vera (Libros Escuela Superior de Guerra, 2018), 41-47, https://esdeguelibros.edu.co/index.php/editorial/catalog/download/28/24/404-1?inline=1. To help advance police capabilities in the region, Colombia, in one year alone, trained police personnel from Guatemala, El Salvador, Panama, Jamaica, Peru, Ecuador, and Brazil. In total, through international cooperation agreements that focus on crimes of kidnapping and extortion, criminal investigation, criminal intelligence, and human rights, Colombia has made a substantial contribution to advancing security, providing assistance to sixteen countries in the region.

Colombia has the potential to become a security hub for the region. Colombia can play a fundamental role in helping to transform the regional security order, moving from reactivity and unilateralism to strategic planning, multilevel coordination, and the institutionalization of cooperation against transitional organized crime. For this to happen, the United States should continue supporting Colombia’s military and police. Although Colombia plays a leading role on regional security issues, greater efforts must be made to ensure the continuity of its leadership as the country grapples with economic challenges and security concerns both internal and external in nature. In addition to the Venezuela crisis, the August 2019 announcement of a “new phase of the armed struggle” by Iván Márquez, a former FARC commander, is a clear indication of the many security challenges facing Colombia. By working with the United States to improve security in Colombia and in the region, the US-Colombia partnership—through efforts such as a joint evaluation of security capacities and security investment plans—can set the foundation for long-lasting prosperity and stability.

A Blueprint for a Modernized US-Colombia Partnership

Over the past decades, Colombia and the United States have consolidated a mutually beneficial partnership that has successfully safeguarded both nations’ security interests. Under Plan Colombia, the country became an increasingly peaceful and prosperous democracy and, together, the United States and Colombia effectively reduced transnational organized crime, violence, coca cultivation, and drug trafficking. Now, with Colombia’s improved security situation, strengthened economy, and increased leadership in the region, the bilateral relationship calls for a renewed partnership.

Instability in neighboring states and interference of extra-hemispheric powers in the region further reinforce the need for a deepened and modernized US-Colombia partnership. After rigorous consultations and discussions, the Atlantic Council’s US-Colombia Task Force identified three major areas that will serve as the foundation for the bilateral relationship going forward: economic development; rule of law, rural development, and the fight against drugs; and joint leadership in the region.

The interests of Colombia and the United States are more intertwined than ever before. The new US-Colombia partnership should recognize this reality, and capitalize on the opportunities that this represents. The partnership will be further solidified as the United States supports Colombia’s efforts to stabilize territories, foster rural development, and bring about a sustainable democratic transition in Venezuela. Economic and diplomatic ties will also be strengthened as both countries work together for the eventual reconstruction of Venezuela and the promotion of stability in other parts of the region, particularly in Central America.

1. Building Sustainable Economic Development and Promoting Innovation

The United States and Colombia stand to benefit from a partnership that promotes economic development in both countries. Bilateral trade and investment offer multiple opportunities for economic growth that will directly benefit both economies. A stronger Colombian economy not only translates to improved living conditions for Colombians but also protects key US national security interests by undermining the drug trade and other illicit economies as well as illegal armed actors. A stronger economic partnership between the two countries will help the United States achieve greater engagement with Latin America to manage current challenges and seize growing opportunities.

The Atlantic Council’s US-Colombia Task Force identified the following three areas as paramount to the bilateral economic relationship: trade and investment; formalization and taxation; and innovation, science, technology, and education. The first area explores opportunities for increased economic growth in both countries. The second area focuses on how to strengthen Colombia’s taxation system and further develop the country’s formal economy. Finally, the third area examines innovative opportunities for mutually beneficial exchange that further both nation’s economic and security interests.

TRADE AND INVESTMENT

With an improved security situation, abundant natural resources, and an educated, growing middle class, Colombia has the potential to become an even stronger economic partner for the United States.27“Outcomes of Current U.S. Trade Agreements,” US State Department, https://www.state.gov/trade-agreements/outcomes-of-current-u-s-trade-agreements/. In 2012, the US-Colombia Trade Promotion Agreement (TPA) took effect. Upon entry into force, 80 percent of US exports of consumer and industrial goods and 50 percent of US exports of agricultural products to Colombia became duty free. The remaining tariffs are scheduled to phase out by 2027. Colombia should consider accelerating the elimination of certain non-agricultural tariffs, with a focus on industries that wouldn’t be disrupted by the removal of such protections, to advance US-Colombia bilateral trade and export flows in line with Colombia’s other bilateral agreements. While US exports to Colombia decreased 16 percent, from $16.4 billion in 2012 to $13.7 billion in 2018, due in part to the sharp depreciation of the Colombian peso, agricultural and manufacturing exports continue to enjoy significant growth.28Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística, “Censo Nacional de Población y Vivienda,” Government of Colombia, 2018, https://www.dane.gov.co/index.php/estadisticas-por-tema/demografia-y-poblacion/censo-nacional-de-poblacion-y-vivenda-2018; United States International Trade Commission, “Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (2018), Basic Edition,” 2018, https://hts.usitc.gov/view/list. According to the US International Trade Commission (ITC), the TPA will expand US exports by more than $1.1 billion and increase US GDP by $2.5 billion.

Fully implementing the TPA represents a significant opportunity for both countries. The results would not only increase trade, jobs, and economic growth, but also improve protections for intellectual property rights, labor rights, and the environment. Moreover, since Colombia’s capacity to continue dealing with the Venezuelan crisis depends on the strength of its economy, the economic bilateral relationship will also benefit both countries’ national security interests. However, for the US-Colombia TPA’s potential to be fully realized, both countries must make changes. Colombia has yet to implement some aspects of the TPA to the fullest, including bills on internet service providers’ responsibilities, commercial agency, and a screen TV quota, the ratification of the International Convention for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (1991) treaty, and allowing for importation of duty free remanufactured goods.

Fully implementing the TPA represents a significant opportunity for both countries.

Employees organize bouquets of flowers to be exported overseas, ahead of Valentine’s Day, at a farm in Facatativa, Cundinamarca, Colombia. The United States is a leading importer of Colombian flowers. (Reuters/Jaime Saldarriaga)

Additionally, strengthened trade and investment between Colombia and the United States will help to provide some counterweight to China’s growing influence in Latin America. Over the last twenty years, trade between China and Latin America has multiplied eighteen times, from $12 billion in 2000 to $224 billion in 2016.29Anabel González, “Latin America – China Trade and Investment Amid Global Tensions,” The Atlantic Council, December 2018, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/images/publications/Latin-America-China-Trade-and-Investment-Amid-Global-Tensions.pdf. Today, China is the largest trading partner for Chile, Peru, and Brazil,30González, “Latin America – China Trade and Investment Amid Global Tensions.” and, in the case of Colombia, China has moved to become its second-largest export partner.31World Integrated Trade Solutions (WITS), “Colombia Trade at a Glance : Most Recent Values,” The World Bank, 2019, https://wits.worldbank.org/countrysnapshot/en/COL. Whereas Chinese investment used to focus on oil and mining and agriculture, it is now expanding to other sectors of the economy including transport, finance, electricity generation and transmission, information and communications technology, and alternative energy.32“China moves into Latin America,” The Economist, February 3rd, 2019, https://www.economist.com/the-americas/2018/02/03/china-moves-into-latin-america. Deepening commercial relations between Colombia and the United States will strengthen the commercial partnership in light of new Chinese economic interest, with the potential effect of having the bilateral relationship serve as a model for other countries seeing new Chinese economic interest.

Implementing reforms geared to decreasing uncertainty for companies seeking to do business in Colombia is also needed, as frequent changes in the tax system and in regulations for different sectors create instability and unpredictability. Colombia and the United States could also work together to identify opportunities for US companies in Colombia. In particular, given the rising tensions between the US and China, several US companies are seeking to relocate from China. The Colombian government and US companies could look for opportunities for mutually beneficial agreements that facilitate their relocation to Colombia. Colombia also needs to give predictability and stability to intellectual property rights by not imposing discriminatory compulsory licenses.

The United States, for its part, should strive to accelerate the process of implementing pending TPA related matters. These include the regional accumulation provision with Peru and other Pacific Alliance countries for textiles and lifting environmental barriers to Colombian palm biodiesel. The US government should also work with the Colombian government to speed up and harmonize sanitary and phytosanitary requirements to facilitate and accelerate the entry of certain Colombian products—mainly agricultural ones—into the US market. Although 105 Colombian agricultural products have preferential access to the US market within the TPA, and seven are currently undergoing the market access process, fewer than ten match the phytosanitary protocols required to enter the United States. This year Colombia is expecting tangible progress for top market-access priorities: fresh peppers, mangoes, pitayas (also known as dragon fruit), papayas, watermelons, cantaloupes, blueberries, and passifloras (yellow passion fruit, sweet granadilla, purple passion fruit, and banana passion fruit).

Thus, the US government could make it a priority for the US Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) to expedite the approval of these products. Colombia, in turn, could prepare to effectively promote and market these products in the United States. Given the importance of reducing coca crops for both the United States and Colombia, devising mechanisms for expedient entry into the US market of agricultural products that are part of crop substitution schemes is also a priority. The United States could also facilitate the entry of Colombian products into the US market by allowing companies to fulfill required processes at competitive prices. For example, Colombian companies could be allowed to carry out product radiation processes in the United States as opposed to Colombia, to reduce costs and logistical barriers. The United States could also work with Colombia to establish a fast-track process for companies that already have the certificate of economic operator authorized by both Colombia’s tax agency, the National Directorate of Customs and Taxation (DIAN), and the Business Alliance for Secure Commerce.

During the last years, Colombia has made enormous progress on labor legislation, due, in part, to the sustained implementation of the Labor Action Plan. The government has increased the number of labor inspectors and issued new regulations to strengthen control over abusive subcontracting methods. Regarding the judiciary, Colombia has made significant progress in pursuing and solving cases related to instances of violence and threats against union members. The United States has recognized this progress. The United States and Colombia can further improve labor conditions by revising their agreement to include success metrics that focus on preventing labor violations rather than only sanctioning them. A modern approach would promote legal flexible labor tools to effectively increase productivity and reduce job informality and unemployment. Examples include temporary work, part-time work, telework, flexible salaries, and subcontracting, among others.33Christian Camilo Vargas Isaza et al., “Tercerización e intermediación laboral: balance y retos,” Asociación Nacional de Empresarios de Colombia (ANDI), June 2019, http://www.andi.com.co/Uploads/Tercerizacio%CC%81n%20e%20intermediacio%CC%81n%20laboral%20balance%20y%20retos%20Colombia%20CESLA.pdf.

There is ample opportunity for increased US investment in Colombia, especially in areas of innovation, science, technology, and agroindustry.

For Colombia’s economy to grow and offer new market possibilities for the United States, Colombian firms need to grow stronger and create jobs. As explored below, a better economic situation is also the most effective and sustainable way to reduce cocaine trafficking from Colombia to the United States. Granting Colombia’s steel and aluminum products entering the US market an exemption from the 25 percent and 10 percent tariffs, respectively, which were imposed under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, would contribute to Colombia’s economic growth. While Colombian exports of these products represent only 0.5 percent of the US market, these tariffs affect the installed capacity and job creation of Colombian companies. Moreover, the Colombian government has implemented several additional antidumping measures against steel and aluminum products coming from countries that contribute to world overcapacity, especially China.

The United States should also continue to support the Pacific Alliance. This alliance, which Colombia helped create, is now considering merging with another regional bloc in Latin America, Mercosur, and wants to bring in more partners and establish new trade deals with Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and Singapore. If this happens, the global economy could experience a tremendous boom. Colombia should continue with its commitment and dedication to solving the different issues that could arise during this process, and the United States should support and even encourage this alliance.

Opportunities for bilateral investment, which benefit both countries, are also growing. Colombia is committed to developing efficient capital markets, creating jobs, and building legal and regulatory systems that meet world-class standards for security and transparency. Its accession to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in May 2018 reflects the country’s attainment of these standards and encourages further investment and economic cooperation. US foreign direct investment (FDI) in Colombia totaled $7.2 billion in 2017 and Colombian FDI in the United States totaled $2.6 billion, supporting 5,500 US jobs.34SelectUSA, “Foreign Direct Investment (FDI): Colombia,” July 2019, https://www.selectusa.gov/servlet/servlet.FileDownload?file=015t0000000LKM6. There is ample potential for increased US investment in Colombia, especially in areas of innovation, science, technology, and agroindustry. As well, Colombia’s acceptance of US federal motor vehicle standards opens additional areas for US investment.

For these opportunities to materialize, Colombia should strive to be more attractive to foreign investors, and can do so by offering more transparent conditions for FDI and reducing regulations, nontariff barriers, as well as cumbersome operations and foreign trade procedures. Strengthening the institutions tasked with ensuring compliance with labor, social security, and tax laws, and increasing coordination among these agencies, will improve enforcement.

Reforming an inefficient tax system should be, as explored below, a priority for future administrations. In addition, Colombia should spotlight itself as an investment destination, showing its potential to become a regional investment hub for the United States. Strengthening the rule of law and gaining institutional control of territories affected by violence, which are discussed later in this report, will also serve to minimize companies’ concerns about political risk and uncertainty.

The United States can help foster conditions for long-term US investment in Colombia. Promoting the double taxation agreement between the two countries would provide investors with legal security and additional incentives for investment. In addition, US foreign policy toward Colombia should avoid producing any uncertainty around the bilateral relationship. The August 2019 certification of Colombia as cooperative in counternarcotics efforts was important to avoid such uncertainty. Any ambiguity in the strength of the relationship negatively impacts investment and commercial flows. Sending the message that the two countries support each other as strategic allies is good for business.

US-COLOMBIA PRIORITIES MOVING FORWARD

TRADE AND INVESTMENT

COLOMBIA

• Implement fully pending aspects of the TPA to increase trade, jobs, and economic growth, but also improve protections for intellectual property rights, labor rights, and the environment.

• Launch structured promotional campaigns for Colombian products entering the US market.

UNITED STATES

• Implement pending aspects of the TPA, including the regional cumulation provision for textiles and increased access to biodiesel products.

• Grant Colombia’s steel and aluminum products entering the US market an exemption from tariffs of 25 percent and 10 percent, respectively.

US-COLOMBIA PARTNERSHIP

• Harmonize sanitary and phytosanitary requirements to accelerate the entry of preapproved Colombian products into the US market. Top market access priorities include: fresh peppers, mangoes, and passifloras.

• Promote the double taxation agreement between the two countries to increase legal security and incentives for bilateral investment.

FORMALIZATION AND TAXATION

A healthy Colombian economy provides the United States with greater market opportunities for goods and services. It can also help to stabilize the territories where illicit groups operate and illicit economies thrive, especially the cocaine market. Two of the most critical barriers to economic development in Colombia are the country’s tax system and high levels of informality. The United States can partner with Colombia to support much-needed reforms to counter these two challenges.

Tax revenues in Colombia have increased consistently from the 1990s to around 15 percent of the country’s GDP today, but remain very low by international standards:35Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), “Details of Tax Revenue – Colombia,” 2018, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=LAC_REVCOL. the OECD average is 26 percent of GDP—a measure similar to that of Argentina (29 percent) and Brazil (26 percent). Part of the problem is Colombia’s tax structure. In Colombia, around 45 percent of these revenues come from taxes on goods and services, which tend to be regressive. Corporate taxes are considered relatively high, with rates of up to 34 percent36The Colombian Government has established a progressive path to reduce corporate taxes from 33 % to 30 % over the next four years. and revenues accounting for 3.8 percent of GDP, which discourages formalization and entrepreneurship. The Duque administration did pass tax reform in 2018, which is currently under revision by the Constitutional Court and aims to progressively lower corporate tax rates down to 30 percent by 2022. Still, in comparison, the average corporate tax in Latin American countries in 2018 was 28 percent.37Daniel Bunn, “Corporate Tax Rates Around the World, 2018,” Tax Foundation, November 2017, 2018, https://taxfoundation.org/corporate-tax-rates-around-world-2018/. Dividends to individuals are taxed at a small percentage, and while this avoids the double taxation of distributed profits, it reduces progressivity. Meanwhile, revenues from personal income taxes represent 1.1 percent of GDP and social security contributions are 2.1 percent of GDP.

The progressivity of the tax system is undermined by generous tax relief and exemptions—there are more than 200 exemptions, representing approximately 30 percent of tax collection—which mostly benefit the wealthier sectors of Colombian society.38Rafael De la Cruz, Leandro Gastón Andrián, and Mario Loterszpil, “Colombia: Toward a High-income Country with Social Mobility,” Inter-American Development Bank, January 2016, https://publications.iadb.org/en/colombia-toward-high-income-country-social-mobility. Colombia’s tax system still needs reforms to enhance progressivity and raise more revenue that can then be channeled to expand social policies. However, an eventual tax reform should maintain corporate taxes at levels comparable to those of other OECD countries. Colombia should also improve transparency and stability in the development and implementation of this updated taxation system.

Tax evasion should also be addressed to strengthen state capacity and foster economic development—this will enhance Colombia’s ability to be a strong economic and security ally to the United States. The DIAN has local branches in only forty-three of the country’s 1,121 municipalities, and the tax officer-to-inhabitant ratio is half the regional average (one to 10,000). Evasion of income tax and value-added tax is estimated to be 4 percent of the GDP, and informality, discussed below, also facilitates tax evasion while reducing the tax base.39De la Cruz, Andrián, and Loterszpil, “Colombia: Toward a High-income Country with Social Mobility.” Overall, the tax system significantly distorts economic activity and has a very small redistributive impact.

Two of the most critical barriers to economic development in Colombia are the country’s tax system and high levels of informality.

Colombia has a large informal economy, equivalent to one-third of its GDP.40Asociación Nacional de Instituciones Financieras (ANIF), “Reducción del efectivo y tamaño de la economía subterránea en Colombia,” May 2017, http://www.anif.co/sites/default/files/investigaciones/anif-asobancaria-efectivo0517.pdf. As of 2015, about 60 percent of firms and 48 percent of workers remained in the informal sector. In the countryside, almost two-thirds of farmers lack formal property titles to their land,41DANE, “Tercer Censo Nacional Agropecuario: Tomo 2 – Resultados,” November 2016, https://www.dane.gov.co/files/images/foros/foro-de-entrega-de-resultados-y-cierre-3-censo-nacional-agropecuario/CNATomo2-Resultados.pdf. and although informality decreased by seven percentage points since 2001,42Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), “Estudios Económicos de la OCDE: Colombia,” May 2017, http://www.oecd.org/eco/surveys/Colombia-2017-OECD-economic-survey-overview-spanish.pdf. it is still a critical barrier to development. Informality negatively affects economic growth as it promotes low-paying jobs, unemployment, and lower productivity by allocating resources ineffectively. Because of this, informal firms have lower access to credit, use more unskilled labor, adopt less technology, perform less training, and have low access to public goods.

Informal firms limit the growth of formal firms as the former do not comply with standards and regulations, which artificially lowers their costs, generating unfair competition. More than half of formal firms in Colombia report that informal firms are one of their top challenges.43The World Bank, “Enterprise surveys : Colombia country profile 2010,” in Enterprise surveys country profile, (Washington, DC: World Bank Group, 2010), http://espanol.enterprisesurveys.org/data/exploreeconomies/2010/colombia#informality. In addition, informality reduces the tax base and access to credit and social insurance for lower income families. Informality also discourages investment and productivity and widens economic disparities across the country, while limiting poverty reduction and the consolidation of the middle class. As an important obstacle for Colombian development, informality compromises efforts to reduce coca cultivation and combat illegal armed groups, therefore undermining US law enforcement and national security interests. Additionally, informality makes it harder for US firms to seize the opportunities that Colombia’s expanding market has to offer.

The United States and Colombia can engage in mutually beneficial cooperation that helps Colombia reduce informality. The two countries should continue training labor inspectors, as they did in a program from 2012 to 2016, with more focus on prevention of labor violations rather than sanctions. Colombia should continue its fight against abusive and illegal subcontracting as well as using legal subcontracting as a necessary tool to increase formality, employment, competitiveness, and productivity. The United States can work with Colombia to devise best practices for achieving several goals. These include streamlining the process for firm creation and closure; reducing unnecessary norms and barriers for firms across geographical divisions; making labor regulations more flexible; and increasing access to credit and other business services. To incentivize formalization, the Colombian government can also engage in public information campaigns to educate workers about the benefits of working in the formal economy (sick days, maternal leave, paid vacation days, etc.). The country also can improve access to credit and other business services to incentivize firms to register their activity and pay taxes.

Improving the modernization process and strengthening the governability of Colombia’s tax agency, DIAN, is of critical importance. Colombia needs to update the software that its taxation system relies on, as it is ineffective and facilitates corruption and money laundering. Strengthening the DIAN and customs agencies—with US assistance—is also a priority because both have been permeated by trafficking groups and other types of criminal organizations. Digitalizing the customs, tax, ports, and airports systems, as well as incorporating blockchain technology would allow for higher traceability of goods and improved intelligence, which favor legal activities and tax collection while creating obstacles for illicit economies. Digitalizing the economy would also benefit US companies doing business in Colombia. The United States could support this process by facilitating the training of engineers. US companies could also contribute by verifying the quality of new information systems.

It is also important to accelerate the process to conduct US immigration procedures on Colombian soil. United States immigration authorities have begun high-level talks with Colombia’s Foreign Ministry to study this possibility. This means that travelers departing the special US designated immigration area in El Dorado Airport in Bogotá would be subject to the laws of the US, and US officers would conduct the same immigration, customs, and agriculture inspections of international air travelers typically performed upon arrival in the United States. A close working relationship on the ground means that authorities from both nations will be able to share information on immigration, customs, and agriculture.

US-COLOMBIA PRIORITIES MOVING FORWARD

FORMALIZATION AND TAXATION

COLOMBIA

• Reform the current tax structure to increase tax revenues while also encouraging formalization and entrepreneurship. An eventual tax reform should maintain corporate taxes at levels comparable to those of other OECD countries.

• Incentivize formalization by educating workers about the benefits of participating in the formal economy, while also offering improved access to credit and other business services.

US-COLOMBIA PARTNERSHIP

• Cooperate to reduce informality and protect formal firms doing business in Colombia. The partnership should work to devise best practices for simplifying the process of firm creation and closure; reduce unnecessary norms and barriers for firms; make labor regulations more flexible to increase formalization, productivity, and competitiveness; and improve the modernization process of Colombia’s tax agency, DIAN.

• Accelerate the process to conduct US immigration customs and inspections at El Dorado airport in Bogotá, Colombia. A close working relationship on the ground will allow authorities from both nations to share real-time information on immigration, customs, and agriculture.

• Collaborate to increasingly digitalize Colombia’s economy, as well as its customs, tax, ports and airport systems, to enhance the traceability of goods, improve tax collection, and undermine illicit economies.

INNOVATION, SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY, AND EDUCATION

For Colombia to achieve the long-term development needed to stop cocaine production and further advance legality, advancements in innovation, science, technology, and education are needed. In particular, for Colombia to keep the high growth rates that maintain advances in poverty reduction and development, it must diversify production and increase productivity and sustainability. Creating legal opportunities in areas affected by violence and illicit economies also requires transforming rural economies. Innovation, science, technology, and education are essential to these quests. The United States has ample experience in these areas and can share best practices with Colombia. At the same time, both countries can engage in new, productive collaborative initiatives, as explained below.

According to the World Bank, in 2017, the total amount of government and private sector funds spent on research and development (R & D) in Colombia was only 0.24 percent of the country’s GDP—an extremely low value compared to the average investment in the sector for Latin America and the Caribbean (0.8 percent). Investment in science, technology, and innovation in Colombia is slightly higher (0.65 percent of GDP). In the 2018 Global Innovation Index (GII), which measures the performance of innovation ecosystems in 126 countries, Colombia ranked sixty-third, below Chile, Costa Rica, Mexico, and Uruguay. In 2017, about 30 percent of science, technology, and innovation funding came from the public sector and 70 percent from the private sector. For R & D, the percentages were 25 percent and 75 percent, respectively.44Alexander Cotte Poveda et al., “Indicadores de Ciencia y Tecnología Colombia 2018,” Observatorio Colombiano de Ciencia y Tecnología, April 2018, https://www.ocyt.org.co/proyectos-y-productos/informe-anual-de-indicadores-de-ciencia-y-tecnologia-2018/.

The United States should work with Colombia to create a development strategy to fund research centers in Colombia. It should be a results-oriented and impact-driven strategy, as are the funding strategies of the United States’ National Science Foundation and National Institutes of Health. The United States could also share its expertise in strengthening industry-university collaboration, given its ample experience in connecting university training with private-sector needs and in promoting innovation by research centers that responds to the needs of firms. Promoting innovation, science, and technology in Colombia will help disrupt the conditions that facilitate illicit activities while also maximizing human capital in this important US free-trade partner.

The United States could also support Colombian efforts to provide technical assistance to firms in order to increase their productivity and prepare them for more sophisticated innovation processes. The United States has significant experience in the design, implementation, and evaluation of such schemes. The US Manufacturing Extension Partnership, for example, has been successful in improving production processes, upgrading technology capabilities, increasing competitiveness of firms, and facilitating innovation throughout the United States.45Ronald S. Jarmin in his 1999 study finds that firms that participated in manufacturing extension partnership (MEP) programs in the United States experienced between 3.4 and 16 percent higher labor productivity growth between 1987 and 1992 than nonparticipating firms. Ronald S. Jarmin, “Evaluating the Impact of Manufacturing Extension on Productivity Growth,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 18, no.1 (1999), 99–119.

Education is another area rich with potential for US-Colombia collaboration. Colombia faces multiple challenges to achieving a high-quality and equitable education system. Given that the transition from illicit to licit economies requires new human-capital development, education in Colombia should be an area of importance to the United States. The United States can make several contributions. For example, Colombia lags behind most Latin American countries in English proficiency. In 2018, it was ranked 60 among 88 countries in the world in this category.46“El ranking mundial más grande según su dominio del inglés,” EF, 2018, https://www.ef.com/wwes/epi/. The Colombian government has tried to increase the number of English teachers, but at least 3,200 more are needed. The United States could help to train Colombian English teachers and provide additional scholarships for US teachers who seek to teach English in Colombia.47Semana, “Colombia y su preocupante nivel de inglés,” April 10, 2017, https://www.semana.com/educacion/articulo/bilinguismo-nivel-de-ingles-en-colombia/542736. At the same time, Colombia could offer education opportunities for US teachers, especially Spanish-language programs, while they teach English in public schools in Colombia. This and other types of exchange programs for language training would benefit both countries.

Advancing the interests of both Colombia and the United States in vulnerable territories requires prioritizing rural education. The Colombian government is creating partnerships with land grant universities to develop programs focused on agriculture. Purdue University, for example, has partnered with Colombia to promote collaborative research, education, and economic development activities. One of the projects consists of a master plan for sustainable development of the Orinoquía region based on analysis-and research-based tools to enable a deeper understanding of the economic and development opportunities related to agriculture and tourism.48“Colombia Purdue Partnership,” Purdue University, https://www.purdue.edu/colombia/. Fostering such partnerships will catalyze initiatives for mutually beneficial collaboration, while contributing to development, stabilization, and legality, all of which undermine the coca industry and the rise of criminal actors.

Colombia and the United States can also broaden opportunities for educational exchange via scholarships, grants, exchange programs, and joint research, aiming to create long-lasting connections between people and institutions in both countries, which, in turn, can promote innovation. About 8,000 Colombians study in the United States every year, with an economic impact of $302 million.49US Department of State, “2018 Fact Sheet: Colombia,” in Open Doors. Report on International Educational Exchange, 2018, https://p.widencdn.net/19i6p4/Open-Doors-2018-Colombia. Approximately 236 of these students receive full scholarships through the Fulbright Program, while others get partial funding through collaborative programs between Fulbright and Colombian agencies. Expanding opportunities for postgraduate training of Colombian students in the United States would make a direct contribution to the development of human capital and economic development in Colombia, which would benefit shared US-Colombia interests.

Similarly, Colombia can become a preferred destination for US students looking to study in Latin America. Today, only around 900 Americans study in Colombia every year—about one-fourth of the number of study-abroad students going to Peru and Ecuador.50US Department of State, “2018 Fact Sheet: Latin America & Caribbean,” in Open Doors. Report on International Educational Exchange, 2018, https://p.widencdn.net/46tto7/Open-Doors-2018-Latin-America-and-Caribbean. Central American countries like Guatemala and Nicaragua receive more than 2,000 American students every year, despite not having any university ranked among the top fifty in Latin America. Colombia, to the contrary, has three universities ranked among the top thirty and one among the top ten.51“Best Universities in Latin America 2019,” Times Higher Education, June 18, 2019, https://www.timeshighereducation.com/student/best-universities/best-universities-latin-america. Colombia can become an important education destination for US students, especially for learning Spanish and studying biodiversity. One government agency, such as the new Ministry of Science, Innovation and Technology, should coordinate different efforts and initiatives to facilitate alliances between US and Colombian universities to promote Colombia as one of the top study-abroad destinations for US students seeking to study in Latin America.

Finally, creating programs specifically for ethnic minorities is also a priority for both countries. The Colombian Ministry of Education is currently advancing an agreement with historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) to provide funding for Afro-Colombian students to study in the United States while offering scholarships for foreign students to study in Colombia. The United States can share its experience in developing programs to support the enrollment of women, ethnic minorities, and low-income students in STEM areas (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics). Exchanging such best practices with Colombia can have a positive impact on education and innovation in Colombia while furthering cultural exchanges.

US-COLOMBIA PRIORITIES MOVING FORWARD

INNOVATION, SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY, AND EDUCATION

COLOMBIA

• Designate one agency responsible for coordinating alliances between universities in Colombia and the United States. Both large and small universities should benefit from this program to ensure that students form all ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds have access to new opportunities. Specifically, the agency should promote collaborative research and education between Colombian and US universities.

• Broaden and increase awareness about opportunities for educational exchanges via scholarships, grants, and study abroad programs, especially for ethnic minorities.

• Promote Colombia as a prime education destination for US students in areas such as Spanish and biodiversity.

UNITED STATES

• The United States can offer trainings to Colombian English teachers and provide additional scholarships to US English teachers seeking to teach in Latin America. While in Colombia, US English teachers will have access to additional education opportunities, especially Spanish language programs.

US-COLOMBIA PARTNERSHIP