For anyone who has sought, over the past seven-plus years, to mitigate the suffering of Syrian civilians, promote political transition, and bring the Syrian conflict to an end, the passing of Kofi Annan on August 18 is particularly poignant. His penultimate role on the world stage was that of United Nations-Arab League Joint Special Envoy for Syria. He played that role with courage, grace, decency, and determination. Had he received the support he merited, Syria would today be in its sixth year of recovery, reconciliation, and legitimate governance.

When he received the joint special envoy appointment in February 2012, Annan moved with dispatch to stop widespread Syrian violence caused by the Assad regime’s successful militarization of the Syrian uprising. He tabled a six-point proposal that, if accepted, would have committed all concerned (1) to work with the joint special envoy on “an inclusive Syrian-led political process to address the legitimate aspirations and concerns of the Syrian people,” (2) to stop the fighting, submit to a United Nations-supervised ceasefire, and cease regime movement toward and operations in populated areas, (3) to insure the provision of humanitarian aid to people needing it, (4) to release “arbitrarily detained persons,” (5) to ensure freedom of movement for journalists, and (6) to respect freedom of association and the right to demonstrate peacefully.

At one point the Syrian government told Annan it accepted his six-point proposal. Yet there was no implementation. Desperate to stop the fighting, Annan successfully pressed for the establishment of a United Nations Supervision Mission in Syria (UNSMIS) under the command of Norwegian Maj. Gen. Robert Mood. This followed a failed attempt to deploy Arab League observers. In May 2012, Mood dispatched observers to various points to witness and report violent incidents. But the security challenges were daunting and the violence overwhelming. Ultimately the Security Council would terminate UNSMIS.

Annan believed that the Security Council’s Permanent Five members, with his assistance, could fashion a political framework that could shoehorn the Syrian armed conflict into a process of peaceful political transition negotiations. He invited the Permanent Five to Geneva in June 2012 to work with him under the rubric of the “Action Group on Syria.” He would perform masterfully, maneuvering the Permanent Five and others to agree, on June 30, 2012, to a Final Communique.

Having served during the early phase of the Action Group on Syria’s work as the representative of the United States, I had little hope that an agreement could be reached. The obstacle was Assad. My French and British colleagues and I wanted Assad explicitly excluded from any Syrian transitional governing body that would replace the regime and guide the country toward representative, legitimate governance. Russia vigorously opposed the exclusion of Assad. China passively supported Moscow.

Even a proposal that individuals with “blood on their hands” be excluded from interim governance roles evoked strenuous Russian objection. “Everyone will know we are talking about Assad,” explained the Russian delegate. He had a point.

In the end, however, Annan squared the circle. The transitional governing body would be peopled by government-opposition bargaining based on “mutual consent.” If the opposition consented to a role for Assad or members of his family and entourage, fine. If not, a veto would carry the day. The same power was vested in the regime with respect to opposition nominees.

To my amazement, Russia signed the Action Group on Syria Final Communique. Moscow had, in effect, endorsed measured, gradual regime change in Syria. The transitional governing body to be created would exercise full executive power. Kofi Annan had, in my view, pulled off a diplomatic miracle.

Alas, it proved to be a mirage rather than a miracle. Both Bashar al-Assad and Vladimir Putin recognized what the Russian delegation in Geneva had signed up to. Assad rejected it, and Putin set in motion a revisionist reinterpretation of what had been agreed. Neither the United States nor Russia behaved with diplomatic skill or finesse in the weeks following Geneva, and the Syrian opposition failed to appreciate what Annan had achieved.

In August 2012, the joint special envoy, seeing that his diplomatic achievement had been wrecked in record time, resigned his position. From that time until now Syria has dived headlong into an abyss.

What I saw in Geneva in June 2012 was a man of impeccable manners and steely resolve deftly maneuvering strong-willed individuals and governments into an agreement that could have ended Syria’s agony eighteen months after it had begun.

The passing of Kofi Annan is to be deeply mourned. Hundreds of thousands of Syrians—innocent civilians, government soldiers, and armed rebels—would be alive today had the regime and Russia been prepared to implement his masterpiece. That they ruined his work confounded Annan and frustrated his successors. They created a smoking ruin of Syria and they imposed on Syrians a humanitarian abomination. They would have done well instead to follow the lead of a great and decent man. Kofi Annan, rest in peace.

Frederic C. Hof is diplomat in residence at Bard College in New York and a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East. Follow him on Twitter @FredericHof.

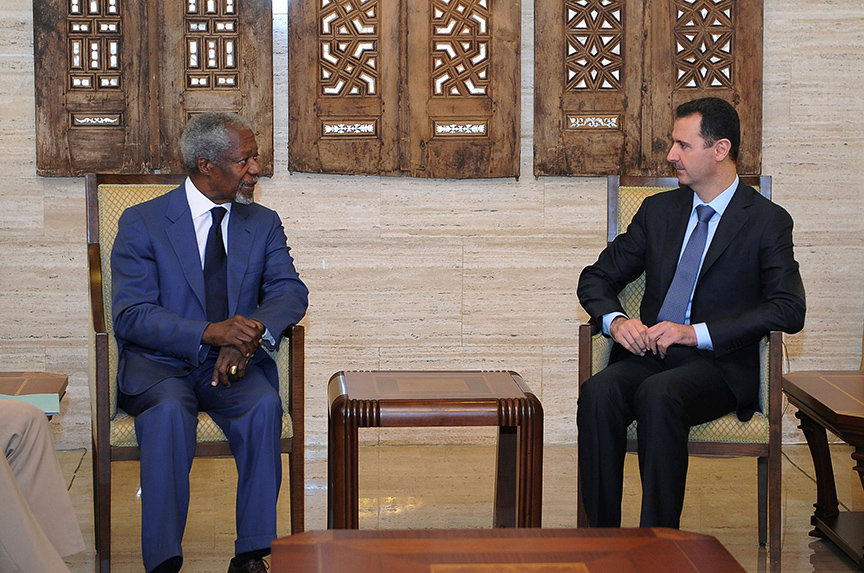

Image: United Nations-Arab League Joint Special Envoy for Syria Kofi Annan (left) met Syrian President Bashar al-Assad in Damascus on July 9, 2012. Annan died on August 18. (Reuters/SANA/File Photo)