Kramatorsk is one of the most American cities that I have encountered in Ukraine. It is not laid out in the walkable format that most Ukrainian towns and villages have. Rather, it has a wide, broad layout, with extensive blocks. It is a city in which a car is almost a necessity. And that is not a mistake. Kramatorsk’s major industry is cars and transport manufacturing; there is a transport school, and far too many car repair shops to count.

Kramatorsk is one of the most American cities that I have encountered in Ukraine. It is not laid out in the walkable format that most Ukrainian towns and villages have. Rather, it has a wide, broad layout, with extensive blocks. It is a city in which a car is almost a necessity. And that is not a mistake. Kramatorsk’s major industry is cars and transport manufacturing; there is a transport school, and far too many car repair shops to count.

In what feels like an attempt to camouflage its industrial nature, Kramatorsk is almost oppressively green. The trees are so leafy and planted so close together that one cannot often see from one side of the street to the other.

The Donetsk People’s Republic briefly held this city of 164,000 for less than three months in 2014, from April 12 to July 5, but little remains from that period. In the two years since the Ukrainian military recaptured the city from Russian-backed fighters that still occupy nine percent of eastern Ukraine, bomb craters and homes have been repaired. Today, Kramatorsk feels calm despite the fighting that continues around thirty-five miles away. It serves as the provisional capital of the Donetsk Region while the city of Donetsk remains under occupation.

There are more uniformed soldiers than one would find in other Ukrainian cities, and the SUVs of the OSCE and UN missions to Ukraine are reasonably normal sights, but tanks and armored personnel carriers don’t roam the streets, shells rarely fall, and the mood on the street is normal. As in other cities throughout Ukraine, patriotic yellow and blue bunting abounds; fence rails and light posts are adorned in the same colors.

But underneath that cheery surface lies a layer of sadness, doubt, and division. Aware that many in Kramatorsk still harbor sympathies for the separatists, the Ukrainian government has devoted special attention to the city, hoping to convince residents of Ukraine’s positive direction. The reformed patrol police recently appeared in Kramatorsk, which is one of the smallest of the thirty-two cities to have been chosen for the new service.

A pro-European line is also heavily promoted. When I was in Kramatorsk in June, the city’s colossal main square, where the plinth of the city’s Lenin statute now stands barren, was hosting a half-hearted summer festival titled “Wild Fields: A Step Toward Europe.”

Walking through the several tents lined up to sell goods, I meet Nadia, a middle-aged woman wearing a vyshyvanka who sells traditional handicrafts to help finance the activities of her group, the Kramatorsk Bees. The Bees are a group of concerned citizens—mostly pensioners or people from the other side of the contact line who have been resettled in Kramatorsk—who spend their spare time helping Ukrainian troops. Their small, cramped headquarters are in the basement of a building just off the city’s main square. There, a dozen people busy themselves ripping old, donated clothes into strips that will be tied onto a net. The finished nets are given to the Ukrainian military where they will be used as camouflage for soldiers.

Nadia, a member of the Kramatorsk Bees, June 2016.

In another corner of the room, a grandmother is creating a ghillie suit for snipers. Making these suits is a time consuming process. The group uses old burlap sacks, which they dye varying shades of green and brown, cut into five inch squares, and then separate the individual threads. They tie groups of these burlap threads onto a netted form that is draped over a mannequin.

Although the fighting between the Ukrainian military and pro-Russian forces has settled into an active stalemate over the past year, the Bees continue their work. Many have friends or relatives who are in the army or have been killed; they are concerned that “Kyiv has forgotten us.”

But other Ukrainians have not. According to the Ministry of Justice, there are more than 490 nongovernmental organizations active in Kramatorsk. One of them, The Lviv Education Foundation, has been active there since the Russian-separatists fled. Volunteers from western Ukraine originally came to help residents rebuild in August 2014. As those tasks have been largely completed, the volunteers have turned their attention to cultural concerns.

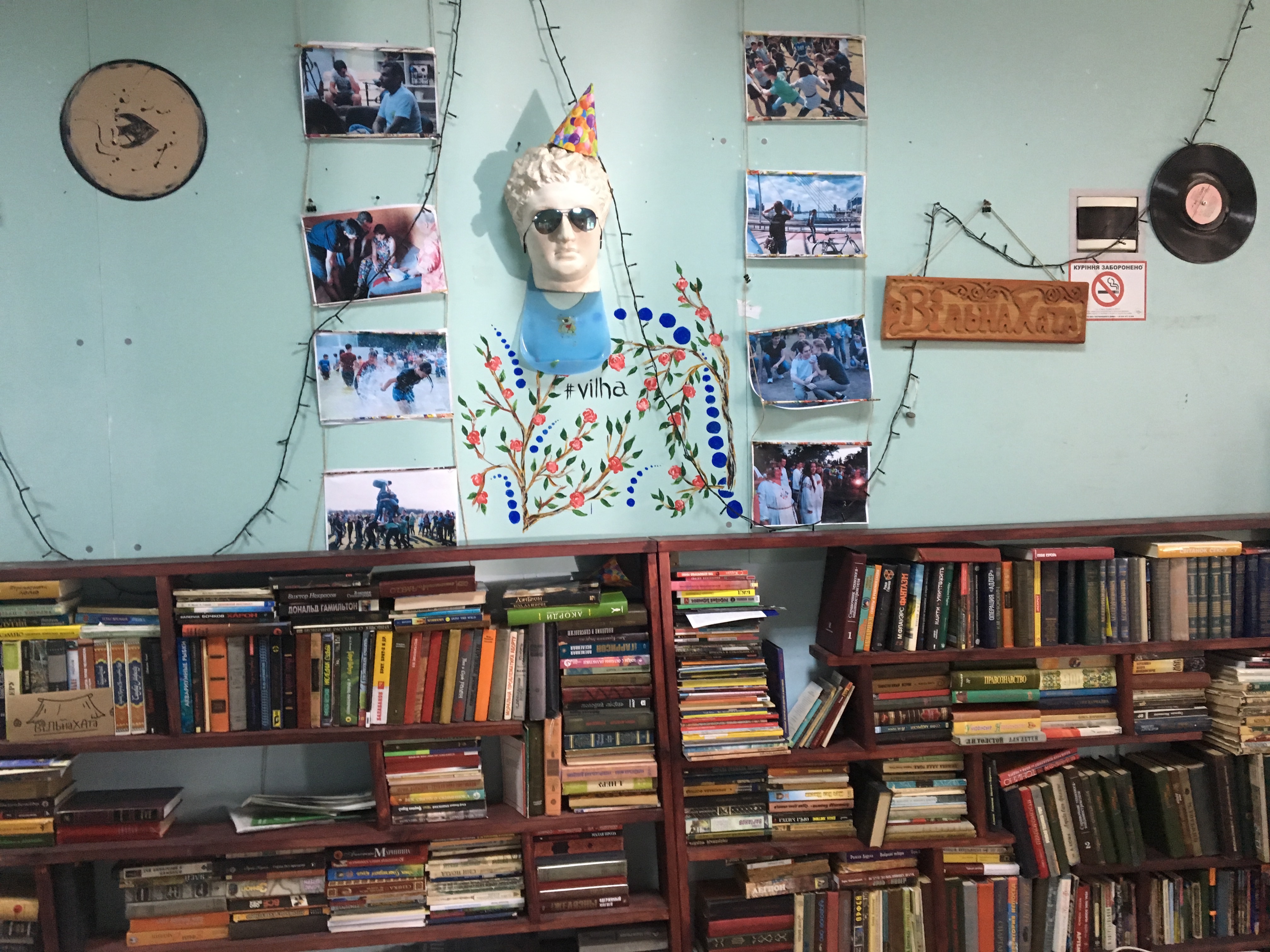

Vilna Khata in Kramatorsk, June 2016.

The group has started Vilna Khata, or “Freedom Home,” in the center of Kramatorsk. A kind of community center, Vilna Khata hosts a full schedule of clubs and events that are designed to bring locals together and help heal the rifts in the community. When I visited on a Saturday, the center was buzzing with activity, and residents from Kramatorsk and its surrounding villages milled about, helped children with crafts, and talked about the situation in the city.

Of course, not everyone in Kramatorsk is happy about their city’s status. Some—like a taxi driver who was suspicious of my accent—are still supportive of Russian President Vladimir Putin and the Russia-backed separatists, but are cautious when saying so. These political fissures run across families, friendships, and workplaces, and still fester. Kramatorsk has a long way to go before the city feels whole again, and full resolution of the city’s issues will certainly not come while the self-proclaimed People’s Republics operate just a few towns away, but the hard work of reconciliation has begun.

Hannah Thoburn is a research fellow at the Hudson Institute.

Image: A map of Ukraine in Kramatorsk, Ukraine. Credit: Hannah Thoburn