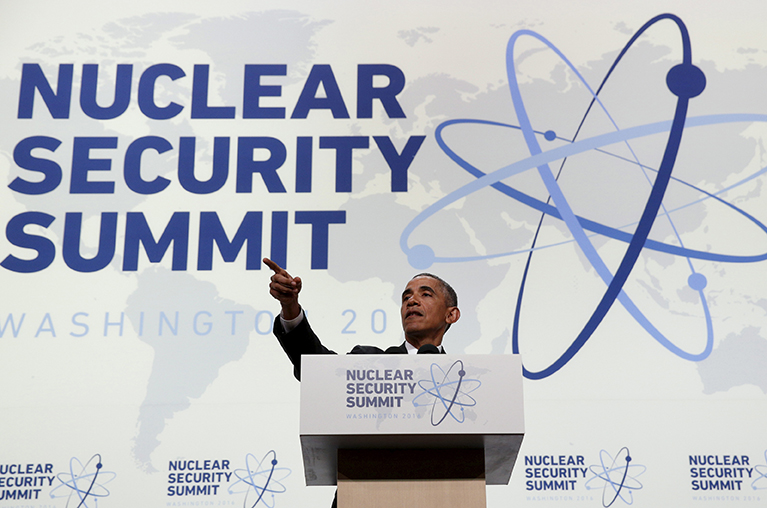

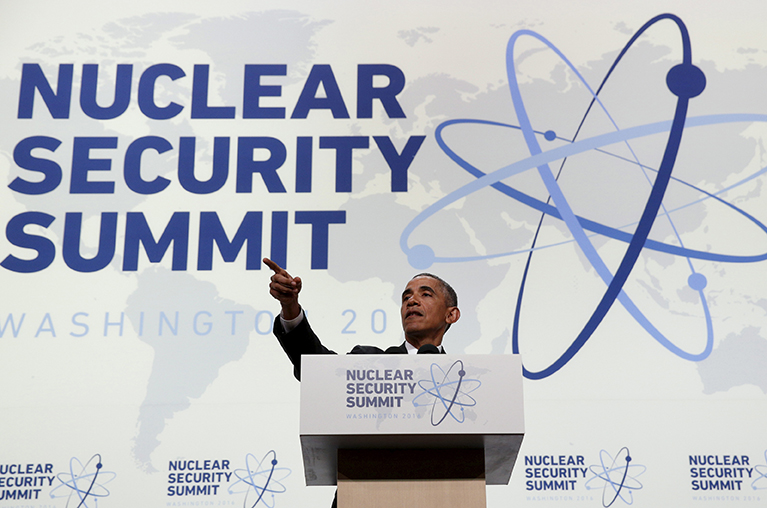

We stand at a historic crossroad with the end of US President Barack Obama’s fourth and final Nuclear Security Summit this past weekend. While it is clear that the progress to date of the global effort to keep nuclear weapons out of terrorists’ hands has been dependent on Obama’s determined leadership, it is not clear what the future holds after he leaves office.

We stand at a historic crossroad with the end of US President Barack Obama’s fourth and final Nuclear Security Summit this past weekend. While it is clear that the progress to date of the global effort to keep nuclear weapons out of terrorists’ hands has been dependent on Obama’s determined leadership, it is not clear what the future holds after he leaves office.

As the official summit process ends—convening world leaders every two years to take action on nuclear security—the threat is growing. The Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) continues its global terror attacks, confounding the intelligence and security capabilities of Europe and elsewhere. ISIS has declared an interest in acquiring a nuclear weapons capability, has claimed to have a dirty bomb capability, and has used weapons of mass destruction—chemical weapons—in Syria and Iraq. We know al Qaeda has the same intent. Our security, the security of our allies and partners, global security is clearly at stake. In order to achieve substantial progress on nuclear security and prevent terrorists from acquiring nuclear weapons, the next President of the United States must continue to provide determined US leadership. Retrenchment is not an option.

Both Obama and former President George W. Bush have described terrorists getting their hands on nuclear weapons as one of the greatest threats to global security. Since Obama first proposed in 2009 the convening of world leaders to address this security threat, these issues have been catapulted to the top of the global security agenda.

With US leadership, much innovative progress has been made in addressing this twenty-first century challenge. Fourteen countries, including Ukraine four years ago, have eliminated their stockpiles of highly enriched uranium and plutonium. These materials have been removed or secured from fifty facilities in thirty countries—a total of 3.8 tons—more than enough to create 150 nuclear bombs. Later this year, Central Europe and Southeast Asia will join Latin America as regions free of these dangerous materials, reducing the risk and, consequently, allowing intelligence and security agencies to target their efforts at the remaining risks. The global nuclear security architecture has been enhanced through training, improved security at nuclear facilities, increased cooperation against nuclear smuggling, strengthened regulations and international guidelines, and deployment of nuclear detection systems at border crossings, airports, and sea ports.

But, the work is incomplete and the threat is becoming more urgent. There remain large and growing global stocks of nuclear and radioactive material around the world that need to be secured. More than 1,800 metric tons of nuclear material remain stored in twenty-four countries and more than 100 countries have thousands of sites that store radiological material that can be used in a dirty bomb, which wraps nuclear materials around a conventional explosive.

The world leaders who attended the 2016 Nuclear Security Summit in Washington from March 31 to April 1 agreed to set up a senior level “Contact Group” to continue to make progress in the relevant international organizations, including the United Nations, the International Atomic Energy Agency, and INTERPOL.

Continued progress on this issue will, however, be very much dependent on the commitment of the next US President and the President’s engagement with world leaders. Unless securing the world’s nuclear materials remains a national security imperative for the next President of the United States, these issues may return to being the stepchild to the more traditional international arms control and nonproliferation agenda and, as a result, receive less attention and resources.

The next US President’s direct engagement with Moscow will also be critical. Russian President Vladimir Putin has cast a large shadow on the future of the global effort to secure nuclear material. As the country that possesses the world’s largest nuclear weapons stockpile, Russia’s responsibility, participation, and support is unquestionable for continued success of this effort. Shunning that responsibility, Putin chose not to attend the 2016 summit well in advance of the meeting, following on his even earlier decision to end bilateral cooperation with the United States on these same issues.

Given the gravity of the challenge and the unimaginable consequences of not meeting it successfully, nuclear security should and must remain on the top of the next US President’s list of priority issues. Time is not on our side. On this issue, US leadership is indispensable.

Lori Esposito Murray holds the Distinguished Chair for National Security at the US Naval Academy. She served as Special Advisor to the President on the Chemical Weapons Convention during the Clinton administration and helped oversee the bipartisan approval of the Chemical Weapons Convention. She is also a former Assistant Director for Multilateral Affairs of the US Arms Control and Disarmament Agency at the State Department. The views expressed in this blog post are her own. Follow her on Twitter @murraylori.

Image: US President Barack Obama has made nuclear security a top priority for his administration. The fourth Nuclear Security Summit—and Obama’s last as President—wrapped up in Washington on April 1. (Reuters/Kevin Lamarqu)