US, Israel, and GCC perspectives on China-MENA relations

This article is part of a strategic collaboration launched by the Atlantic Council (Washington DC), the Emirates Policy Center (Abu Dhabi), and the Institute for National Security Studies (Tel Aviv). The authors are associated with the initiative’s Working Group on Chinese and Russian Power Projection in the Middle East. The views expressed by the authors are theirs not their institutions’.

Great power competition is increasingly dominating the way in which US-China relations are analyzed. This prospect is a troubling one in regions around the world as it leads to an unappealing binary choice when complex policy problems require a wider set of options and coordination between global powers.

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) is one such region, with deep longstanding relations with the United States and growing economic, technological, and development relations with China. This piece summarizes perceptions of China’s growing MENA presence from three vantage points: the US, Israel, and the Gulf monarchies.

US perspectives on China-MENA relations

US perspectives of China in the MENA have to be considered within the context of US-China relations globally. There are regions where the two powers’ interests are in competition—this isn’t necessarily one of them. Both countries want a stable MENA, with energy flowing to global markets and freedom of navigation maintained in vital shipping lanes. Apart from Iran, China’s closest partners in MENA are US partners and allies, a fact that underscores Beijing’s preference for the regional status quo. There is room for US-China policy coordination on issues of shared concern in the Middle East if they are able to separate the regional issues from the global ones.

Politically, this is difficult. Both countries have contributed to a worsening bilateral relationship. Under President Xi Jinping, China has adopted a more assertive foreign policy both in substance and in tone. It has been more willing to throw a punch and the rise of its aggressive “wolf warrior diplomacy” in other regions has not made for a more constructive environment, with officials using social media to deliver hostile and occasionally insulting messages about countries they feel are unfair to China.

Under the Donald Trump administration, China policy was also combative, reflecting a changing US view on China that crosses party lines. For successive US administrations, America’s China policy was shaped by strategic engagement with the expectation that deeper economic and political ties would ultimately result in a more open domestic environment amenable to US values and interests. Xi’s ascent and Beijing’s ensuing hard authoritarian turn has ended that belief, and strategic engagement has been replaced with strategic competition.

This makes it hard but not impossible for the two powers to have a constructive relationship in MENA. China’s signature approaches to developing a MENA presence—its strategic partnership diplomacy and the 1+2+3 cooperation pattern, under which it targets key sectors to develop bilateral relations with Arab countries—seemed designed to complement rather than challenge US interests in the region.

However, in the current environment, nearly every aspect of China’s MENA engagement seems to present Washington with political or security concerns. When China’s regional ambitions were limited to being a major trading partner or contractor, there was no problem. Both President Barack Obama and Trump complained of Chinese freeriding, but the fact is that lots of US partners and allies have been doing the same for decades. But, as Chinese firms are making inroads into the digital realm where there are issues of data protection and standard-setting, the US is increasingly concerned about the implications of China playing a greater role in MENA.

This is going to require serious diplomatic engagement from the Biden administration. China won’t simply leave the Middle East and Middle Eastern countries are happy to have another interested great power investing, building, and trading in the region.

The US and China are going to have to find a way to work together in MENA. The alternative is to turn the region into a great power contest, an outcome that nobody wants.

Israel perspectives on China-MENA relations

In the Middle East, the US has no closer ally than Israel and China is well aware of Israel’s deep strategic ties to the US. Simultaneously, within the Communist Party and the Chinese public, Israel’s image has strengthened as a powerful, important, and stable country in the region, creative with unique technological and scientific innovation capabilities.

Following the establishment of diplomatic relations between Israel and China in 1992, some Chinese leaders and scholars believed that good relations with Israel could assist China in reaching Washington’s ears, which affected China’s eagerness to develop better cooperation with Israel. Following two incidents in 2000 and 2005 of US demands for Israel to stop selling military equipment to China and the continued growth of China’s superpower-status, this reasoning has lost its relevancy. However, the fact that Israel is a firm ally of the US should not prevent, by Chinese view, the cultivation of commercial ties along civilian lines.

While having little knowledge on China, many Israelis, as well as the Israeli media, suspect its intentions in the Middle East in general and towards Israel in particular. They are comparing the enduring US support of Israel to China’s lack of support as well as its systematic votes with Arab and Muslim countries in international fora, and tend to believe that China does not really understand or care about Israel’s existential concerns, particularly relating to malign Iranian activities within the region. While China is proud of its abilities to maintain parallel relationships with Middle Eastern countries that are enemies—such as Israel and Iran—Israel does not view this in a positive light and any news on China and Iran’s strategic cooperation is a source of concern.

At the same time, Israel recognizes China’s commercial importance, being its second-largest trade partner. Therefore, it seeks to maintain a civilian-economic cooperation with China in non-sensitive areas, while finding a balance between economic need and strategic concerns. Accordingly, in the foreseeable future, Israel will remain deeply committed to its special strategic relationship with the US, while maintaining lines of communication with China and trying to explore areas of civil commercial cooperation. Therefore, the Abraham Accords may lead to a new path of economic cooperation, as the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states could be a bridge for new projects with Israeli and Chinese partners, leading to a broader civilian cooperation between China and the region’s countries.

The Gulf states’ perspectives on China-MENA relations

The GCC states and China have developed a relationship of interdependence to maintain each other’s economic development. In terms of strategic objectives, China and most Gulf states share the ultimate goal of bringing stability to the MENA region. Besides, their virtual consensus derives from the fact that both would like to bank on the US security structure as the sole guarantor of the regional status quo.

The Gulf region’s strategic location is crucial for linking the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) infrastructure projects and economic corridors in Asia with Europe. The Abraham Accords signed between the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Bahrain and Israel consolidates the US-led regional alliance. However, they also underscore prospects for closer China-Gulf-Israel cooperation in the economic, trade, and technological spheres.

Nearly half of China’s oil imports also come from the MENA region. The shale-oil revolution in the US left no option for the GCC states but to look east, a new dynamic that could be considered a shift in economic relations from the old industrial powers to the new ones.

But the rise of the strategic competition between China and the US created a major predicament for the Gulf states. At the same time, the most powerful GCC members—namely Saudi Arabia and the UAE—recently showed a rising degree of frustration with US policy in the Middle East and continue to see the US as a less reliable regional actor. The coronavirus fallouts accelerated the debate in the GCC states about adopting a policy of strategic hedging in their relations with China and the US.

This is not to suggest that the GCC states expect China’s more assertive foreign policy under Xi to soon translate into a struggle to topple the US from its position as the underwriter of Gulf security. The GCC states, particularly Saudi Arabia and the UAE, see some US policies and narratives across successive administrations as a source of concern in regard to Washington’s commitment to their security. China’s rise and its growing economic and trade ties with the region could present the Gulf states with a profound opportunity to mount pressure on the US to show a more substantial commitment to their security, the stability of their regimes, and their regional agendas.

Although China and the US might agree on some core regional principles—mainly stability and freedom of navigation—competition in the Middle East is expected to intensify. This is due to the growing centrality of the technological domain in GCC-China relations. Additionally, the exponential proliferation of China’s interests will inevitably add a security layer to China’s role in the region. Therefore, a policy that resembles a balancing act is expected to be seen by the Gulf states to be able to safely navigate between these two giants.

Conclusion

The MENA region is going through a transitional period a decade after the first wave of the Arab Uprisings, with issues of governance and development continuing to dominate many countries throughout the region. Middle Eastern order is contested, as fierce rivalries characterize much of the region’s international politics and spillover effects from bloody sectarian and national conflicts in Syria, Yemen, and Libya. At the same time, there is a much broader transition at the global level, with the US-led order facing pressures from a rising China. Taken together, this all adds up to a serious set of challenges for Middle Eastern states and makes it a difficult terrain for the US and China to navigate.

On the flip side, the news isn’t all bad. Diplomatic ties between Israel and the UAE, Bahrain, Morocco, and Sudan all give reason for optimism and provide opportunities in the face of challenges.

Dr. Jonathan Fulton is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council. He is also an assistant professor of political science at Zayed University in Abu Dhabi. Follow him on Twitter: @jonathandfulton.

Amb. Dr. Eyal Propper is a senior research fellow and head of China Program at the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS). Before INSS he served as Consul-General of Israel in Shanghai (2017-2020). Follow him on Twitter: @epropper.

Dr. Ahmed Fahmy is a senior researcher at the Emirates Policy Center (EPC).

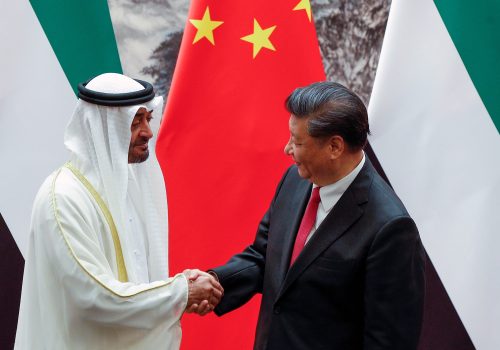

Image: Prime Minister and Vice President of the United Arab Emirates and Ruler of Dubai Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashed al-Maktoum meets with Chinese President Xi Jinping at the Presidential Palace in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates July 20, 2018. WAM/Handout via REUTERS. ATTENTION EDITORS - THIS IMAGE WAS PROVIDED BY A THIRD PARTY.