China is happy about the Abraham Accords and the GCC crisis coming to an end

In recent months, two major events in the Middle East—a burst of diplomatic relations for Israel and the end of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) crisis—have changed the regional landscape. Both episodes were driven by regional actors responding largely to pressures and opportunities within their countries and the broader Middle East, while the role of the United States has been an important factor. Though China was not involved in either development, change in the Middle East presents opportunities for Beijing as well.

The dramatic announcement that the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Israel were normalizing relations on August 14, 2020 was the first such event. While deep ties between Israel and the GCC countries were the worst-kept secret in the Middle East, there was little indication that they were ready to take this step. China was clearly caught off-guard; Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesman Zhao Lijian was tepid in his response the day after the announcement, referring only to China’s ongoing support for Palestine. Given Chinese cooperation with both the UAE and Israel, however, it is clear that normalization supports Beijing’s regional interests.

For one thing, it facilitates cooperation between two of China’s most important Middle East and North Africa (MENA) partners in its Digital Silk Road (DSR) initiative. Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI), a Chinese artificial intelligence (AI) company referred to as the “Huawei of genomics,” signed an agreement in 2019 with Abu Dhabi’s Group 42 (G42), a firm that is central to the UAE’s growing AI ambitions. Little noticed at the time, the agreement came into the spotlight in March 2020 when the two companies were used to support the UAE’s COVID-19 response by providing tracking and tracing technology.

BGI has made inroads throughout the Middle East and also signed an agreement to build a coronavirus testing lab in Israel. Several Chinese tech companies, including Alibaba, AliExpress, and Huawei, have made inroads into Israel with digital investments, and Israel is seen as an important partner in the DSR. The UAE and Israel have been quick to cooperate in tech sectors; G42 announced plans to open an office in Tel Aviv, where they expect to collaborate on AI research, agricultural and water supply technology, renewable energy, and smart city development. A UAE-Israel tech axis creates a DSR foothold in the Middle East for Chinese firms.

Geopolitically, China also benefits from Israel having normalized ties with Arab countries in the Gulf. The European Union is China’s largest trading partner, making the Mediterranean Sea a major endpoint in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). An Israel integrated into its own region provides yet another important access point to the Mediterranean, especially if and when connecting infrastructure comes into effect. The proposed Red-Med railway and the ambitious “Tracks for Regional Peace” that would link Haifa port to the Gulf underscore Israel’s geostrategic importance. This is especially crucial for China’s BRI ambitions of cross-regional connectivity.

In short, Israel’s growing diplomatic role in the Middle East is a net good for almost everyone and, like many countries with interests in the region, China stands to benefit.

The second major event was the end of the GCC dispute. As with diplomatic normalization, China had nothing to do with this, but it stands to gain here as well. In ending Qatar’s isolation, the US seems to have been a major consideration for decision-makers in Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Bahrain, and the UAE. President Donald Trump’s initial support for the blockade was a trigger, much like President Joe Biden taking office was a trigger for its end. This is largely a story about long-standing tensions on the Arabian Peninsula—made more complicated by partnerships and alliances with the US.

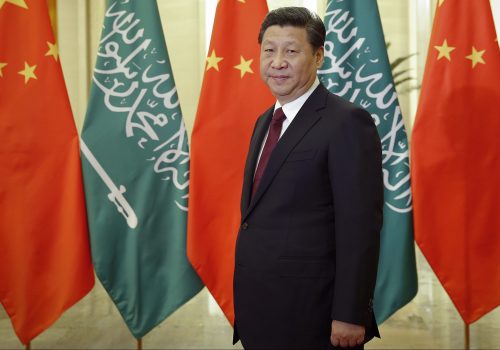

Where does China fit in? In the year leading up to the crisis, China and the GCC had held four rounds of talks to finalize a free trade agreement that they’d been negotiating on-and-off since 2004. During President Xi Jinping’s state visit to Saudi Arabia in January 2016, he made it clear that China was ready to get serious about the deal and set 2017 as a deadline. Negotiating a multilateral deal with the Gulf Cooperation Council was not going to happen with a broken GCC, so it’s been on hold. We can expect to see talks resume soon, which will facilitate a China-GCC free trade agreement that will have important consequences for an already impressive set of economic relationships.

The shifting MENA context also matters because relations between China and Qatar have been on the back burner since 2017. In 2014, Emir Tamim bin Hamada al Thani visited Beijing for a state visit and signed a strategic partnership agreement. There was serious momentum, with over $8 billion in infrastructure and development contracts, including the high-profile Lusail Stadium—the opening and closing venue for the FIFA World Cup in 2022. Industrial and Commercial Bank of China’s Doha branch was designated as a renminbiclearing center in 2015, making it the first institution in the Middle East to cover transactions in Chinese yuan and was used for a remarkable $86 billion worth of deals by the time of the crisis. This burst of momentum halted with Qatar isolated in the Gulf, while other countries, especially the UAE, enjoyed a surge in deals with China.

The BRI features here as well. It’s a series of projects promoting connectivity, and since 2017 Qatar has connected to very little. With Qatar presumably coming back into the fold, it will likely enjoy a corresponding spike in Chinese projects.

China isn’t unique in these two cases. Middle Eastern dispute resolution benefits lots of countries with interests in the region and several can be expected to capitalize. However, given China’s increasingly deep MENA footprint, it will capitalize more.

Jonathan Fulton is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council. He is also an assistant professor of political science at Zayed University in Abu Dhabi. Follow him on Twitter: @jonathandfulton.

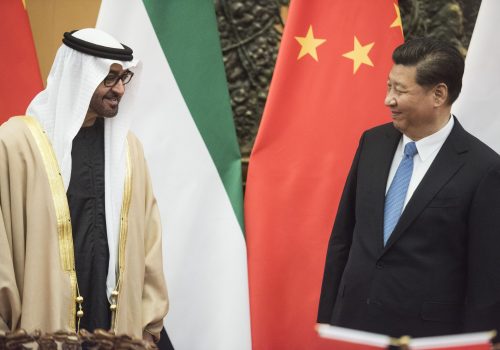

Image: Abu Dhabi's Crown Prince Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, left, shakes hands with Chinese President Xi Jinping after witnessing a signing ceremony at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, Monday, July 22, 2019. Andy Wong/Pool via REUTERS