Strangers to strategic partners: Thirty years of Sino-Saudi relations

This year marks the thirtieth anniversary of diplomatic relations between China and Saudi Arabia. Over the past three decades, the bilateral relationship has transitioned from one of marginal importance for both countries to a comprehensive strategic partnership, largely on the back of a trade relationship founded on energy.

This report begins with a brief historical overview of Sino-Saudi relations, describing how the two countries transitioned from mutual hostility to diplomatic relations, and then how political and economic cooperation strengthened the relationship to the point that they signed a comprehensive strategic partnership in 2016. It then discusses how the partnership has developed through the 1+2+3 cooperation pattern, especially through projects linking China’s Digital Silk Road with Saudi vision 2030, as well as nascent levels of security cooperation. It ends with an analysis of the bi- lateral relationship within the context of the US-Sino-Saudi triangle: How does it affect each state’s larger strategic interests, and can issues where their interests diverge put a ceiling on future Sino-Saudi ties?

Key findings

The expansion of the Sino-Saudi bilateral relationship has been a result of mutual interests, an evolving strategic landscape, and the complementary nature of policy initiatives, namely China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Saudi vision 2030.

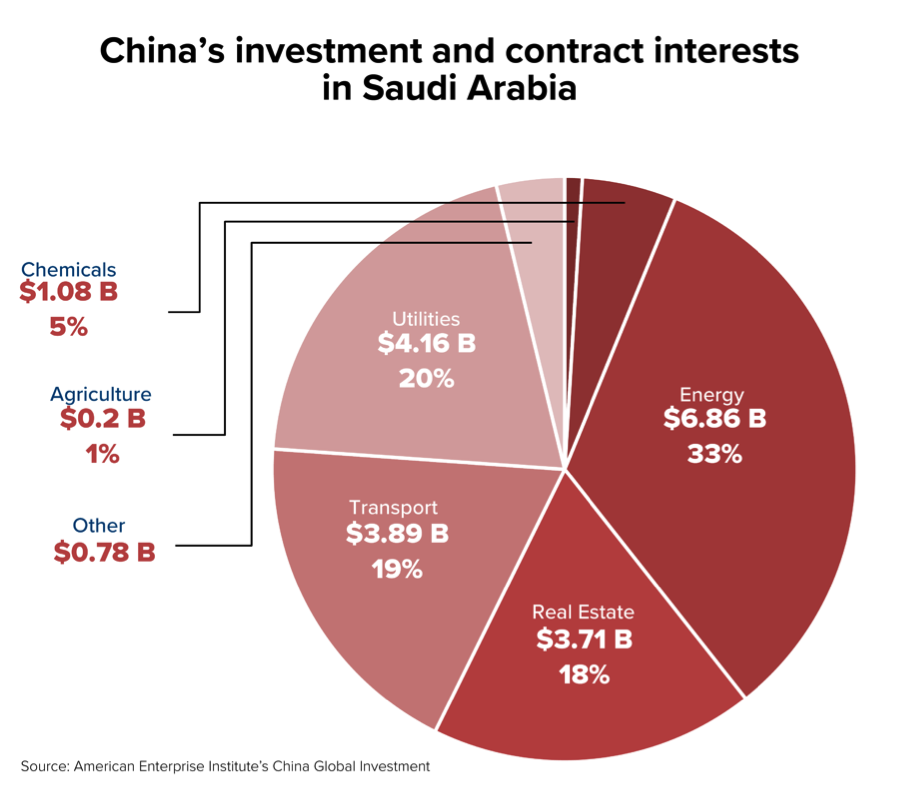

For China, Saudi Arabia occupies an important geostrategic location, has prominence in global Islam, and is an energy superpower, which together make relations with the kingdom a central pillar of Beijing’s Middle East policy.

For Saudi Arabia, China is its largest economic partner, both in terms of energy trade and as a source of investment in Saudi Vision 2030 projects.

For Saudi Arabia, China is its largest economic partner, both in terms of energy trade and as a source of investment in Saudi Vision 2030 projects. The perception that US commitment to the region is wavering makes engagement with other extra-regional powers important to Riyadh.

Saudi Arabia still leans heavily on the United States, and the prospect of an American exit from the Gulf, as exaggerated as this prospect is, would pose considerable threats.

US policy is internally conflicted. Washington has conveyed clear statements of a desire to limit US involvement in the region, while simultaneously forcing its allies to choose between relations with Washington and Beijing.

Key recommendations

In the context of intractable security threats and intense regional political and ideological rivalries, China may find some aspects of its policy toward Saudi Arabia unsustainable in the long run.

China will need to decide whether it wants to risk the Middle East becoming a theater for great power confrontation, given growing US- Sino tensions. Since US power in this theater is likely to exceed China’s for years to come, it would be wise for Beijing to focus on expand- ing its economic, diplomatic, and cultural relationships with Saudi Arabia.

China will need to better address the inherent contradiction between its desire to improve relations with Saudi Arabia, which presents itself as a leader of the world’s ummah, and its increasingly brutal treatment of many of its Muslim citizens.

Riyadh may be hedging against a US withdrawal by accelerating its engagement with China, but it should take care that its efforts do not in fact drive the very dynamic it is looking to avoid.

Leaders in Saudi Arabia also have to make some decisions about how to effectively manage a balanced approach between Washington and Beijing. Riyadh may be hedging against a US withdrawal by accelerating its engagement with China, but it should take care that its efforts do not in fact drive the very dynamic it is looking to avoid.

The United States could assuage concerns that it plans to abandon the region by clearly signaling a commitment to working with its partners, especially Saudi Arabia, while enhancing the economic and development role it plays in the region.

Policy makers in Washington should identify clear “red lines” for Saudi Arabia and the rest of the region in their growing relationship with China and clarify the ramifications if those red lines are crossed.

At the same time, the United States has to make a convincing case that these “red lines” are justified and present a credible alternative. There is an obvious example in Sino-Saudi digital cooperation.

Lastly, decision makers in the United States need to recognize that the interests and objectives of China do not always run counter to those of the United States. The United States should work with China to develop a common agenda for the region that out- lines ways in which the two can collaborate—and should explicitly state that it wants to avoid, if at all possible, the Gulf becoming a theater for great power confrontation in the years ahead.

Watch the launch event

Related content

Through our Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East and Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative, the Atlantic Council works with allies and partners in Europe and the wider Middle East to protect US interests, build peace and security, and unlock the human potential of the region.

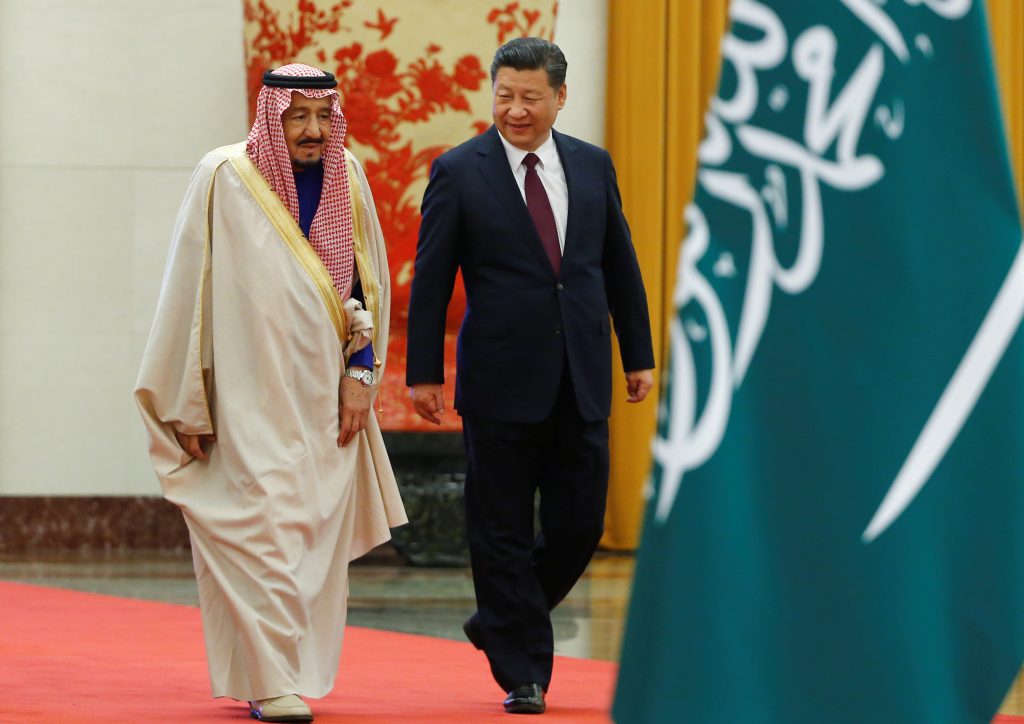

Image: China's President Xi Jinping and Saudi Arabia's King Salman bin Abdulaziz attend the Road to the Arab Republic--the closing ceremony of the artifacts unearthed in Saudi Arabia--at China's National Museum in Beijing, China March 16, 2017. Photo credit: Reuters/Lintao Zhang/Pool