Demography and geopolitics put Japan’s strength to the test

Table of contents

Evolution of freedom

The only non-Atlantic member of the G7, Japan is a country that defies easy categorization. Even as it has experienced comparative macroeconomic stagnation over the past three decades, Japanese companies have remained innovative and the country as a whole remains prosperous. While the persistence of Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) leadership has led some to characterize Japan as an immature democracy, it also enjoys enviable political stability and its democratic institutions and culture have deep-rooted foundations. Even as Japan has been criticized for its overly rigid labor markets, it has earned admiration for low levels of inequality, high levels of safety, and the stoic persistence of the Japanese people in the face of recurrent natural disasters. Both the great strengths of Japan and the many challenges that it faces ahead are in sharp relief in this year’s Freedom Index, which makes a continued and important contribution to our understanding of the dynamics of freedom around the world. In this essay, I explore several of these trends, offering potential explanations and—at times—respectful disagreements, as well as suggesting opportunities for Japan to continue to strengthen the foundations of its freedom and prosperity in the years to come.

As the Freedom Index recognizes, Japan is among the world’s leading democracies, with well-developed institutions and a mature economy that promote a high degree of freedom and prosperity for its citizens and residents. Notably, the country’s scores in the political and legal subindexes are both significantly above the OECD average and have experienced only minor fluctuations in the last three decades. That Japan is a stable and mature democracy is reflected not only in the Freedom Index but other well-known indices such as those released by the Economist Intelligence Unit and Freedom House.

At the same time, as the Freedom Index recognizes, Japan has further opportunities to strengthen the foundations of its own democracy and prosperity. This is perhaps most evident in scores in the economic subindex of the Freedom Index, which lag behind Japan’s scores in the political and legal subindices. In 2023, Japan’s economic score fell six points below the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) average and lagged behind peer countries such as Australia, Germany, and the United States by approximately ten points. This gap is explained largely by poor performance in two components: women’s economic freedom, and investment freedom.

Regarding the former, the underlying data used to construct the component (the World Bank’s Women, Business and the Law index) point to two important aspects in which Japan’s legislation does not reach the same standards of gender equality as other developed countries, specifically equal pay, and workplace protection. Although “womenomics” was a major theme of former Prime Minister Abe’s premiership from 2012–20 and has remained a priority in subsequent administrations, it is true that there is still work to be done.

In particular, Japan has struggled to right the so-called “M-curve” whereby women in their thirties have much lower labor force participation rates than younger and older age groups, often reflecting temporary withdrawal from the workforce in the early stages of child-rearing. Although this phenomenon is evident in many developed countries, structural rigidities and other distinctive features of Japan’s labor market and work culture have had the effect of limiting women’s ability to return to career-track roles after childbirth. Although the most recent national data suggest significant improvements in this area, the persistent gap between female and male labor force participation in managerial roles attests to the continued importance of this challenge.

The evolution of investment freedom in Japan is also distinct from many other developed nations. In general, Japan has averaged a ten- to twenty-point gap between the OECD average since 1995, though this gap has narrowed somewhat since 2004, reflecting in part liberalization efforts introduced by the Koizumi and Abe administrations as well as sustained improvements in Japanese corporate governance standards. These have had an important effect over time in attracting additional foreign investment, which has helped to improve Japan’s score. Anecdotally, foreign involvement in state-supported strategic national projects, such as a joint Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC)-Sony-Denso semiconductor fabrication facility in Kumamoto, also attest to more welcoming attitudes and approaches to both foreign direct and portfolio investment. In light of contemporary trends in economic analysis, such as work by the International Monetary Fund and other international institutions to highlight the pernicious economic effects of inequality, it is also reasonable to question whether Japanese labor protections that count against its economic freedom score are truly a mark against economic freedom. An alternative reading might suggest they are instead an example of the kind of stakeholder capitalism that institutions such as The Business Roundtable have called for the United States and others to embrace.

As for Japan’s score on the political subindex, high marks reflect the extraordinary stability of Japan’s democratic institutions, not only since 1995 but over the last sixty years. To be sure, some commentators have argued that the persistent dominance of the LDP throughout most of the postwar period suggests Japan is an immature democracy. However, the success of the Democratic Party of Japan (2009–12) in capturing a sweeping majority—and then the clear electoral rebuke that followed persistent policy missteps and returned the LDP to power—demonstrate the ability of the Japanese electorate and Japan’s democratic institutions to both generate change and support a peaceful transition of power. Further, a major reason for the LDP’s persistent electoral success has been its willingness to adapt and accommodate a wide range of political views from moderate conservatism to right-wing nationalism. Political leadership is strongly supported by the bureaucratic system, which has been the driving force of the policymaking process.

Even the visible (if relatively small in magnitude) drop in the Freedom Index’s civil liberties component in 2019 can readily be explained by restrictions imposed to try to tackle the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, as evidenced by the subsequent rebound in 2022. A similar fall is observable in the Index’s rating for legislative constraints on the executive. In this case, the drop has been persistent but the cause—and implications—of this drop are worth evaluating critically. One potential explanation is the fact that the national legislature did not decisively condemn multiple scandals related to political appointees in the executive branches and several members of the Cabinet during the late Abe administration (2012–20) and across the Suga and Kishida administrations (2020–24). At the same time, in foreign policy circles, the emergence of a more empowered and decisive Japanese premiership has been widely lauded as vital in allowing Japan to cope with an increasingly complex and severe foreign policy environment. Given that effective foreign policy is a critical guarantor of Japan’s economic freedom—and a critical buttress for the rules-based international economic order that Japan seeks to uphold—these scores deserve cautious interpretation.

By contrast, the reduction in political rights observed in the Index—though relatively small—is nonetheless a cause for sober reflection. This drop in particular coincides with the former Prime Minister Abe’s second term. Abe’s strong leadership had many positive effects but its treatment of the press at times did not live up to the ideals of Japanese democracy. For example, certain journalists were practically expelled from press conferences when the administration felt their questions were unfair, which can be seen as an indirect restriction of freedom of information. This minor episode reflects a pressure that was looming over journalism in Japan, where the law regulating broadcasting gives an extraordinary importance to the neutrality of public and private media outlets (see Article fourof the Broadcasting Act of Japan).

Finally, the most notable trend in the legal subindex, which seeks to capture bureaucratic quality and control of corruption, showed a more than fourteen-point improvement from 2002 to 2014, perhaps reflecting the legacy of major government restructuring efforts launched by the Hashimoto administration (1996–98) and carried forward under the subsequent Koizumi administration (2001–05). These gains have since been somewhat sustained, reflecting perhaps the intermittent revelation of corruption scandals, such as a notable case concerning Japan Highway Public Corporation in the 2000s and the recent incident affecting several ministers of the LDP accused of misuse of political donations.

Evolution of prosperity

Just as it is free, Japan is also among the most prosperous countries of the world, a reality well reflected by its high scores across the Prosperity Index. However, rather than dwell on Japan’s considerable strengths, I will focus here primarily on several caveats that highlight challenges ahead for the Japanese economy.

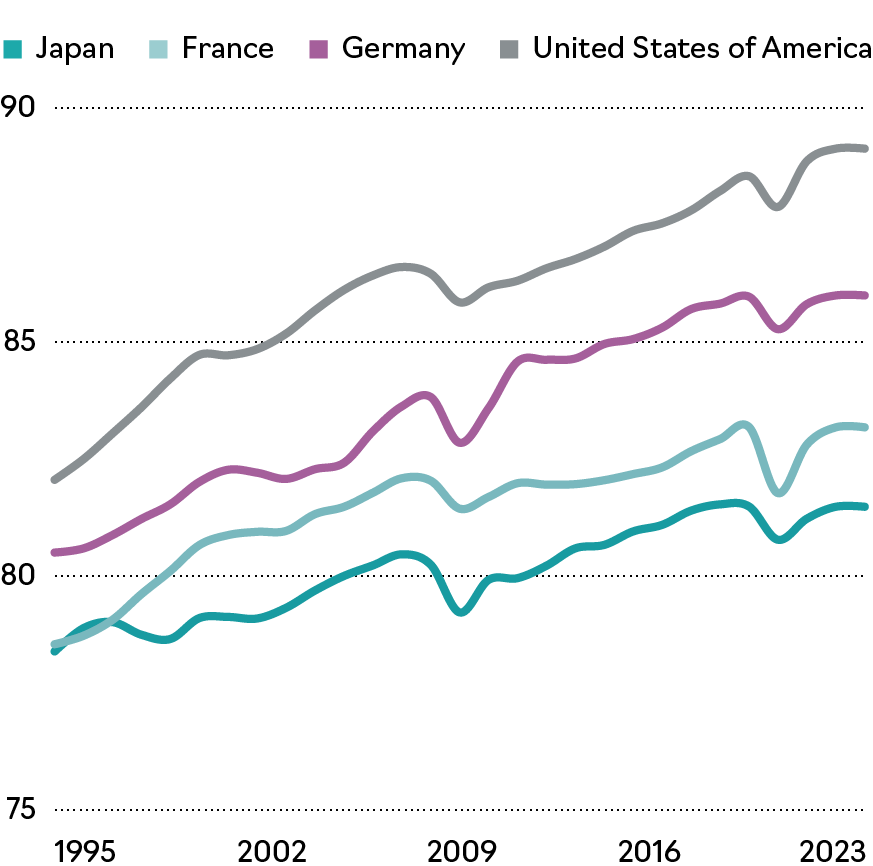

First, although Japan is prosperous, growth in both gross domestic product (GDP) and income over the past two decades has been extremely limited. This in part reflects a basic reality that maintaining high levels of growth at the economic frontier is always difficult, particularly following the global financial crisis and in the shadow of rising public debt burdens around the world. Nonetheless, it is also true that Japan has underperformed even relative to most of its G7 and developed country peers, leading to a widening gap in income levels between Japan and the United States, France, and Germany (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Change in Income for Selected Countries (1995-2023)

Source : World Bank GDP per capita, PPP

Second, Japan has experienced a slow rise in economic inequality since the start of the millennium. This is especially notable given the emphasis that Japanese culture and policy place on equality and homogeneity. Although in comparison to both large developed countries such as the United States and large developing countries such as the People’s Republic of China, Japan remains an almost shockingly egalitarian country, it is nonetheless true that policy efforts to increase the level of competition and productivity across the Japanese economy are correlated with increases in inequality. Whether it is these domestic policy changes that have caused inequality to rise, or whether it is structural shifts in the international economy that have led, for example, to many Japanese firms increasing the share of flexible contract employees over protected permanent employees, is unclear. However, the reality that a growing share of Japanese households are facing economic instability and seeing their incomes eroded by rising food and energy prices is unambiguous and a pressing policy challenge.

Finally, it is worth commenting on Japan’s performance in terms of education. Once more, when compared to the global or regional average, Japan’s score stands as relatively high. Japan’s education system has long been regarded as one of the best in the world, with high literacy rates and a strong emphasis on the fields of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics. For example, Japan exceeded the OECD average for number of fifteen-year-old students amongst the top performers in the OECD Program for International Student Assessment (PISA). Nonetheless, the picture is not so optimistic when noting that Japan’s gap with respect to countries such as Germany or the United States is very sizeable (twelve and six points respectively). This gap could be explained partly by the lack of recognition of the importance of higher education. With the aging population, the need for lifelong learning and reskilling workers have become challenging priorities for Japan.

The path forward

Looking forward to what the evolution of freedom and prosperity for Japan may look like in the near future, I would like to touch upon four major challenges that Japan may face.

First is its demographic challenges. Japan is one of the most rapidly aging societies in the world with a shrinking working-age population. According to the World Bank, Japan’s population growth rate has been negative since 2011, and the decreasing workforce also means that there are fewer contributors to social security systems, exacerbating already strained public finances. The government is making various efforts to tackle this issue, including policies to increase the birth rate and address rural depopulation. However, their effects are limited in scale and scope. Immigration policy also remains relatively restricted and, while the necessity of reform is obvious in any macroeconomic analysis, the political economy of large-scale immigration is one where Japan closely resembles its developed country peers: there are no simple answers on offer. These policy areas could be considered both as difficult challenges and potential opportunities for growth.

Second, Japan has substantial opportunity to more assertively promote diversity, equity, and inclusion. For example, couples married under current law are not allowed to elect to maintain separate surnames, despite a clear public majority in favor of such a reform. Same-sex marriage also enjoys strong public support and is even being considered in some local municipalities but progress at the national level has been slow across both the legislative and judicial branches. As discussed above, Japan also has further room to expand economic opportunities for women. When combined with other strategic labor market reforms, this could lead to significant productivity gains.

Third, the shifting labor and investment market may affect Japan’s scores in the Freedom and Prosperity Indexes. As noted, Japan’s labor market used to lack flexibility and maintains significant structural rigidities when compared with most developed Western economies. Even today, most Japanese who join a company or government agency as regular employees out of college will think of their career with that institution in terms of decades rather than years. This stability of employment and accompanying seniority-based wage hikes have certain virtues in cultivating skilled, dedicated core employee bases. At the same time, locking away talent within companies and limiting incentives for top performers to excel may have reduced incentives and opportunities for innovation and entrepreneurship. Further, strong protections for some sections of the workforce may have come at the expense of others; as illustrated by the aforementioned rise in the frequency of dual-track employment structures. In this sense, as Japanese companies look to build job-type employment structures, they have an opportunity to square this circle, maintaining the low levels of inequality for which Japan is rightly praised while also providing more opportunities for flexible and dynamic career paths that will promote economy-wide productivity gains (and, hopefully, better work-life balance).

Last but not least, the increasingly severe security and geopolitical circumstances surrounding Japan are likely to shape the country’s domestic political economy. A belligerent North Korea and the rising threat of a Taiwan Strait contingency remain as important regional security threats, while the situations in Ukraine and the Middle East are also of concern for Japan. In concert with the United States and like-minded partners, Japan is preparing itself for such contingencies while also seeking to proactively reduce the risk that they will occur. As part of this general trend, there is increasing discussion about a potential amendment to the Constitution of Japan, including a part of Article Nine. In some respects, such reforms might be seen as weakening Japan’s freedom—and may well register as such in the Freedom Index—but their actual impact is a matter of interpretation. Likewise, as US-People’s Republic of China tensions have contributed to Japan’s implementation of a world-leading economic security program, measures undertaken to promote Japan’s economic autonomy may alternatively be interpreted by some stakeholders as undermining economic freedom.

As Japan prepares in 2025 to mark the eightieth anniversary of the end of World War II, it faces an uncertain political and economic future and a complex and challenging international security environment. However, the roots of freedom, prosperity, and democracy run deep in Japan, and Tokyo’s continued commitment to promoting a free and open rules-based international order is clear. Further, Japan’s ability to build a model of capitalism that delivers both freedom and broad-based prosperity is worth learning from, just as Japan must continue learning from its developed country peers as well as the Global South.

Kotaro Shiojiri is a Japan Foundation visiting scholar at the Wilson Center, fellow at the Edwin O. Reischauer Center for East Asian Studies at Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies, and visiting associate professor at the Graduate Schools for Law and Politics at the University of Tokyo. Shiojiri earned his BA in law, MA in international studies, and PhD in public policy from the University of Tokyo, and his LLM from Harvard Law School.

Statement on Intellectual Independence

The Atlantic Council and its staff, fellows, and directors generate their own ideas and programming, consistent with the Council’s mission, their related body of work, and the independent records of the participating team members. The Council as an organization does not adopt or advocate positions on particular matters. The Council’s publications always represent the views of the author(s) rather than those of the institution.

Read the previous Edition

2024 Atlas: Freedom and Prosperity Around the World

Twenty leading economists and government officials from eighteen countries contributed to this comprehensive volume, which serves as a roadmap for navigating the complexities of contemporary governance.

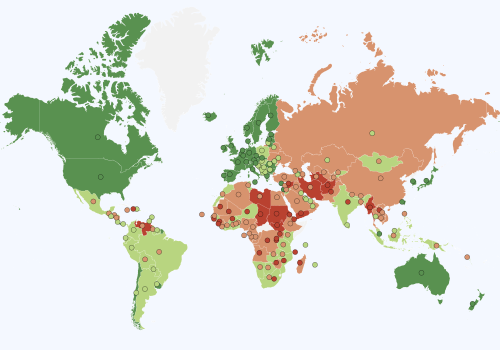

Explore the data

About the center

The Freedom and Prosperity Center aims to increase the prosperity of the poor and marginalized in developing countries and to explore the nature of the relationship between freedom and prosperity in both developing and developed nations.

Stay connected

Image: Japanese Rio 2016 Olympics and Paralympics athletes wave to fans during a parade in Tokyo, Japan, October 7, 2016. REUTERS/Shizuo Kambayashi/Pool

Keep up with the Freedom and Prosperity Center’s work on social media