Note: This article was updated on April 23 to reflect Dodik’s attempted arrest.

Milorad Dodik has dominated politics in Bosnia and Herzegovina’s (BiH) Republika Srpska entity for most of the past two decades. But a court ruling earlier this year has put his political future in question, and the response to his legal troubles has instigated perhaps the greatest institutional crisis in BiH since the end of the Bosnian War in 1995.

In late February, a BiH state court sentenced Dodik to one year in prison and a six-year ban on holding public office for defying the decisions of the Office of the High Representative, the international body overseeing the implementation of the postwar Dayton Accords. If this sentence is enforced by a second-instance ruling expected later this year, then Dodik—who has been sanctioned repeatedly by the United States and United Kingdom for corruption—would no longer hold any formal power.

As is often the case with strongmen who equate their personal destiny with that of their people, Dodik framed the verdict as an enemy attack on the Republika Srpska, and he doubled down on secessionism. The Republika Srpska assembly passed laws blocking state-level institutions from operating within the entity and approved a draft constitution claiming the Republika Srpska’s right to self-determination. Ethnic Serbs were invited to abandon several state-level institutions, while a Republika Srpska army and judiciary were also announced. Then in early March, it was revealed that since December, Dodik had also been under investigation in a second case on charges of attacks against the country’s constitutional order. His failure to appear for questioning led to the issuance of a warrant for his arrest.

While BiH’s constitutional court has suspended the Republika Srpska’s separatist laws, the legal and political quagmire exposed the difficulty that BiH institutions face in exercising their authority in the Republika Srpska. Dodik threatened that his security team and the Republika Srpska police would clash with any BiH agency willing to arrest him. On April 23, BiH special police reportedly attempted to arrest Dodik during a visit to East Sarajevo, but were deterred by heavily armed Republika Srpska police units.

This crisis has also exposed the lack of unity in the European Union (EU) on how to handle Dodik. He still enjoys the strong backing of countries such as Hungary, which reportedly even sent special police units to extract him in case of an arrest. Despite the harsh condemnation of his actions by Western officials and the hardening of sanctions against him by Germany and Austria, many in the West still worry that his arrest could trigger a broader security crisis in the Balkans and would prefer to see Dodik make a more orderly exit from office.

Yet by crossing these major red lines for regional security and openly challenging the authority of the BiH government, Dodik has also exposed his weakness and desperation. With a possible dead end in sight for his secessionist threats, Dodik’s main external backers might already view him as more of a liability than an asset.

Who would follow Dodik down the rabbit hole?

This latest episode is merely the most extreme case of a consistent pattern: Dodik instigates a crisis to extract personal concessions from domestic and international actors. In this case, he is stoking a constitutional crisis, likely in the hopes of winning concessions on his legal troubles and keeping himself in power. His saber-rattling counts on Western fears (as evident in dramatic media headlines) that he will push BiH and the Balkans back into war if he does not have his way. While an attempt at Republika Srpska secession would almost certainly lead to a regional conflict, the number of actors who have already shown they are not willing or capable of supporting Dodik down this rabbit hole indicates, at least for now, that his threats lack credibility.

This includes first and foremost Bosnian Serbs, many of whom share Dodik’s secessionist goals, but may not view the dismantling of state-level institutions, let alone a new war under current circumstances, as serving the interests of the Republika Srpska. There was reportedly no enthusiasm for Dodik’s calls to leave state-level jobs in the entity, while Bosnian Serb opposition parties also denounced the move as self-serving.

The experience of Serbs in northern Kosovo provides a cautionary tale that Bosnian Serbs may be heeding now. In April 2023, northern Kosovo Serbs boycotted local elections, which resulted in Albanian candidates winning with a miniscule turnout of less than 3.5 percent. Only a year ago, it was Dodik himself who warned that a boycott of BiH institutions could lead to a similar scenario for Bosnian Serbs.

Dodik’s gambit also rested on foreign-policy miscalculations. His hopes that the Trump administration would shift US Balkans policy in his secessionist direction were rebuffed by Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s clear condemnation of his actions in March. Russia certainly continues to have an interest in turning the region into a new hotspot to distract Western attention and resources from Ukraine. Dodik himself appeared in Moscow on April 1, and he was given a reception with Russian President Vladimir Putin. Yet there are clear limits to what Russia can do to support the secessionist movement, especially if Dodik’s key backer and neighbor Serbia does not greenlight it.

How Serbia’s leader sees the situation

The leverage that this situation has given to Serbian President Aleksandar Vučiċ illustrates why he has been Dodik’s key backer and enabler over the past decade. Much like the case of Kosovo’s Serbs, Dodik’s troublemaking has been a useful tool for Vučiċ to fuel nationalist narratives at home while maintaining plausible deniability and an image of “constructiveness” in his relations with the West.

Dodik’s political fate may now be a bargaining chip in the hands of Vučiċ, who leads a country drifting toward authoritarianism and who constantly hedges and negotiates with the West on problems he creates. Considering Vučiċ’s own difficult domestic situation, with a large-scale and enduring student protest movement that has threatened his power and shattered his image abroad, it would not be a surprise if he sacrifices a distressed and expended asset like Dodik to the West to further his own goals. If Dodik were to lose Vučiċ’s backing, he would be unable to continue paralyzing Bosnian institutions with his secessionist threats and may have to respect the final court sentence or seek exile in Moscow or Budapest.

The West seems to be done buying Dodik’s threats of regional instability and largely appears determined to see him leave office, whether that means his arrest or resignation and exile. But while Dodik leaving office would be good for BiH and deterrence against Republika Srpska secessionism in the short term, the West is not adopting the same attitude toward his enablers in Belgrade and Budapest.

In defiance of the EU, Vučiċ recently stated that he would join the World War II victory parade in Moscow on May 9 and invited Russia’s Federal Security Service, or FSB, to “investigate” claims that sonic weapons were used against Serbian student protesters (of course, no foul play was found). This most recent foreign-policy signaling by Vučiċ illustrates that while Dodik’s political future seems grim, the underlying conditions behind his troublemaking in Moscow and Belgrade will remain undeterred, waiting for more opportune moments.

Agon Maliqi is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center. He is a political and foreign policy analyst from Pristina, Kosovo.

***

The Western Balkans stands at the nexus of many of Europe’s critical challenges. Some, if not all, of the countries of the region may soon join the European Union and shape the bloc’s ability to become a more effective geopolitical player. At the same time, longstanding disputes in the region, coupled with institutional weaknesses, will continue to pose problems and present a security vulnerability for NATO that could be exploited by Russia or China. The region is also a transit route for westward migration, a source of critical raw materials, and an important node in energy and trade routes. The BalkansForward column will explore the key strategic dynamics in the region and how they intersect with broader European and transatlantic goals.

Further reading

Fri, Mar 7, 2025

What Trump’s approach to Europe means for the Western Balkans

New Atlanticist By

Shifts in US policy toward Europe could prompt the EU to step up on security for the Western Balkans and revive the enlargement process.

Tue, Feb 4, 2025

Fearmongering from Western Balkan leaders is no longer working on their citizens—or the EU

New Atlanticist By

The European Union has ample leverage to press its concerns on reforms, Russia policy, and regional stability to Western Balkan countries.

Fri, Sep 27, 2024

Renewables offer opportunity in the Western Balkans. But challenges remain.

EnergySource By

The Western Balkans rely heavily on aging coal plants for electricity production, with five of its nations generating about 40 to 95 percent of their electricity from lignite, leading to significant pollution and related health issues. Tens of thousands of megawatts of solar and wind projects have been proposed, but despite policy incentives and investor appetite, five key challenges remain.

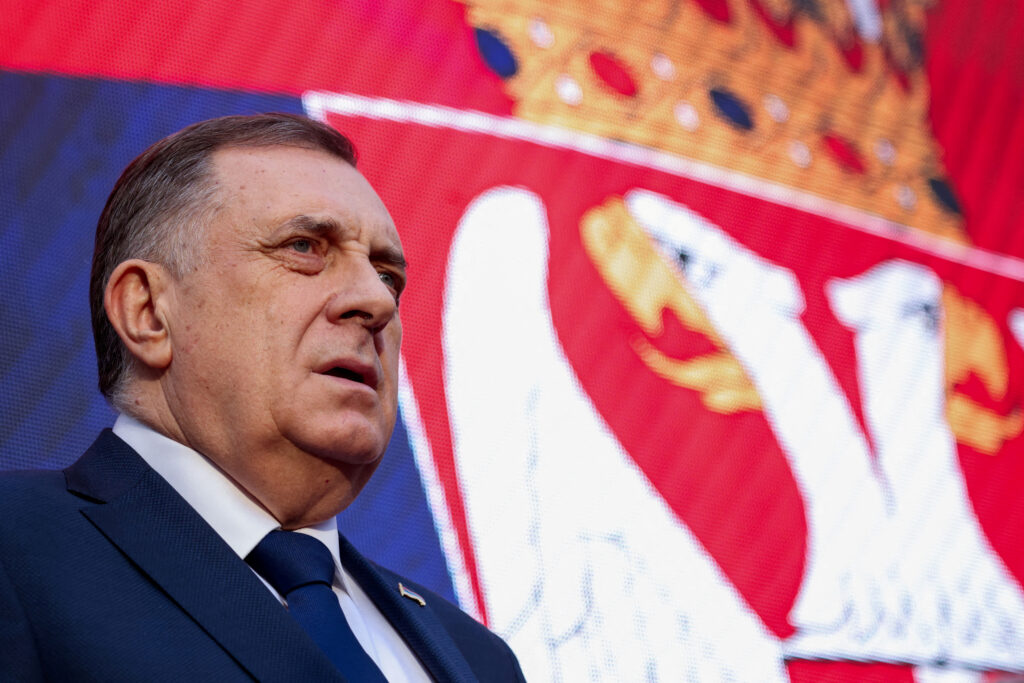

Image: President of Republika Srpska (Serb Republic) Milorad Dodik attends a protest in Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina, February 25, 2025. REUTERS/Amel Emric.