The twelve-day war between Iran and Israel, which the United States joined with airstrikes against the Iranian nuclear program, has shaken up the foreign-policy calculus for the Islamic Republic.

What happens next will have implications for regions well beyond the Middle East. That is partially because a cornerstone of Iran’s foreign policy is its deepening engagement with Africa, particularly in military engagement and technology transfers. Tehran has framed its investments in the continent as part of a broader anti-imperialist resistance to the West, and it has elevated the continent to a strategic priority.

The fallout from this war could seriously hamper this growing influence in the short term. But depending on how the regime reacts, it could be a different story over the long run.

Hard and soft

Iran’s “drone diplomacy” has been a cornerstone of its foreign policy approach in recent years. Iran has deployed such diplomacy across the African continent, most notably in Sudan, a key gateway to the Red Sea. It is suspected that Iran has been providing the Sudanese Armed Forces with military equipment since the two countries resumed diplomatic ties in October 2023.

But Iran has also exercised an increasing amount of soft power on the continent. It has increased the number of Iranian ministerial and presidential visits to the continent, as well as the deployment of increasingly sophisticated soft power tools, many with a religious nature. These include the establishment of Islamic institutes in over thirty African countries, the provision of free social services by the Iranian Red Crescent Society and the Imam Khomeini Relief Committee, and missionary activities conducted by Al-Mustafa International University. Government-supported IranRadio launched Hausa TV in Nigeria in 2017, presenting it as the first Iranian radio and television channel dedicated to the African continent.

Why Africa?

There are three primary reasons why Iran would focus on Africa.

The first is ideological. Seeking to break out of its diplomatic isolation, Iran has continued to work to expand its Axis of Resistance against Israel and the United States. Tehran saw Africa—particularly the Sahel, where it perceives a rise of anti-Western sentiment—as a historic opportunity. In 2022, the Iranian foreign minister visited Mali, a country whose 2020 coup was the first in a series of takeovers in the Sahel. In 2023, in meetings with Malian security officials, the Iranian defense minister was quoted as saying, “the Islamic Republic of Iran will spare no effort to strengthen Mali’s defense power against the threats posed by terrorist groups.”

The second is political. African partnerships play an important role in Tehran’s strategy regarding its nuclear program and human rights. It is worth noting that African countries represent 28 percent of the votes at the United Nations, a forum that has raised concerns in the past about Iran’s human rights record and nuclear development activities.

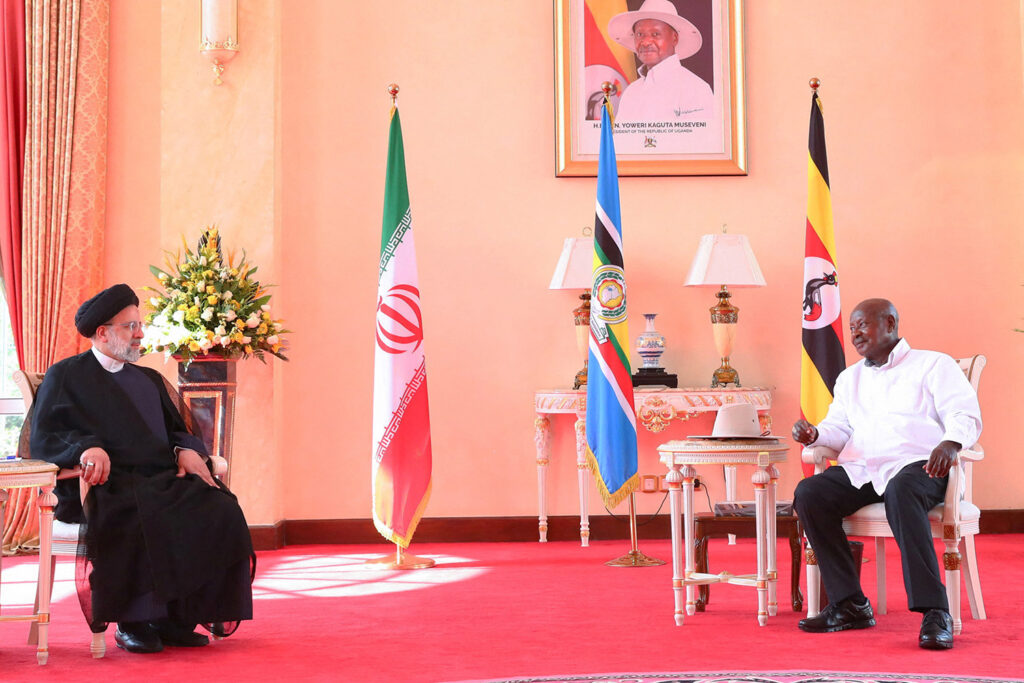

Iran has worked to strengthen its bonds with Africa on such issues, as demonstrated by former Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi’s praise for Uganda’s anti-LGBTQI+ legislation, using anti-Western rhetoric, when he visited the African country in 2023 during a three-country tour of the continent. “The Western countries try to identify homosexuality as an index of civilization, while this is one of the dirtiest issues,” he said. In addition, Burkina Faso, which has been under military rule since 2022, signed a memorandum of understanding for cooperation on peaceful nuclear applications with Iran. This is probably why, on June 12, Burkina Faso was the only African country to vote against the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) resolution condemning Iran for “non-compliance” with its nuclear obligations. Russia and China also voted against the resolution.

Nevertheless, many African countries support Tehran’s right to develop a civilian nuclear industry, calling for its use to be peaceful. This explains why countries such as South Africa, Ghana, and Egypt, as well as India, Indonesia, and Brazil, abstained in the IAEA vote. These votes echoed a joint statement issued on June 17 by twenty-one countries, including ten African states, which condemned Israel’s airstrikes on Iran and urged de-escalation; it also called for a nuclear-weapon-free zone in the region.

The third reason is an economic one. In 2024, it was reported that Iran secured a secret deal for three hundred tons of refined uranium from Niger, raising alarm in Washington. Iran’s interest in accessing commercial markets in Africa—including uranium from Niger, gold from Burkina Faso and Mali, and cobalt from Uganda—can be attributed, at least partially, to its efforts to circumvent the heavy sanctions imposed by the United States and gain access to key components for its defense systems. For some of these African countries, for example Niger (which is also under sanctions), this renewed cooperation with Iran may seem like a godsend.

Iran has also pursued other avenues of economic cooperation with African countries. During his cross-continent trip in 2023, the former Iranian president also visited Kenya, which is now a major non-NATO ally. Kenyan President William Ruto designated Iran as “a critical strategic partner” and announced the signing of five bilateral memoranda of understanding in various sectors, including information technology and fisheries. And this year, Tehran secured a joint economic cooperation agreement with Niger that spans sectors including mining, energy, industry, and technology.

For Iran, losing Africa would have substantial economic consequences. Iran’s push into Africa is taking place amid growing investments from Gulf states in Africa and rising competition between the Gulf states and Iran on African soil. Although Iran’s trade with Africa currently represents only 3 percent of Iran’s total exports and 1 percent of its total imports, the value of Iran-Africa trade has at least doubled since 2021. Today’s figure is estimated at between $800 million and $1.3 billion, but Iran is targeting an annual trade volume of ten billion dollars. In pursuit of improving economic cooperation, Tehran reportedly hosted seven hundred business leaders from thirty-eight African countries at the third Iran-Africa Cooperation Summit in April.

What comes next

The Israeli and US strikes could result in Iran abandoning its pivot to Africa to focus on its own stability.

But they could also reinforce Tehran’s resolve to accelerate its African engagement. It is possible that the challenges Iran faces in the region will force it to seek greater support in Africa in order to strengthen its position in the Middle East. This would be similar to how Russia leveraged African resources and anti-West anger to fuel its war in Ukraine. But that would require the regime to have a considerable amount of resilience—and for the great power competition already taking place on the continent to unfold in a way that is advantageous for Iran and its messaging.

Thus, what ultimately happens in Africa with respect to Iran’s influence depends on the future of the regime in Tehran.

For each African country, a relationship with Iran offers both opportunities for development cooperation and risks of becoming entangled in broader geopolitical tensions that could ultimately undermine their own stability and international standing.

Rama Yade is the senior director of the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center.

The Africa Center works to promote dynamic geopolitical partnerships with African states and to redirect US and European policy priorities toward strengthening security and bolstering economic growth and prosperity on the continent.

Further reading

Mon, Jun 30, 2025

Africa’s game revolution is loading

AfricaSource By Tom Bonsundy-O’Bryan

With the right investment, infrastructure, and visibility, Africa won’t just be a player in the global gaming industry—it will be the one pushing it forward.

Fri, Jun 27, 2025

In Seville, leaders have an opportunity to tackle systemic global inequality. Will they take it?

AfricaSource By

Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals at the global level increasingly depends on progress being made in Africa.

Fri, Jun 27, 2025

Don’t leave Africa behind in sports sustainability—put it first

AfricaSource By

The hosts of the upcoming Olympic Games and FIFA World Cup are committing to sustainability goals inside their countries. But achieving a sustainable sports legacy will take a global approach.

Image: Former Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi meets with Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni during his official visit at the State House in Entebbe, Uganda, on July 12, 2023. Photo by Iran's Presidency/West Asia News Agency via Reuters Connect.