Why the rule of law is the key to prosperity: Lessons from thirty years of data

Bottom lines up front

- Thirty years of global data are clear: The rule of law is the most influential factor for long-term economic growth and societal wellbeing.

- Countries with robust rule of law see greater progress in political and economic reforms. Legal clarity, judicial independence, and accountability create the foundation for successful governance and thriving markets.

- Rule of law is declining worldwide, even in advanced economies. Reversing this trend requires coordinated reforms and investment in judicial capacity from governments, donors, and the private sector.

Table of contents

- Rule of law is the strongest driver of prosperity

- The rule of law is an enabler of political and economic reforms

- Case in point: Rwanda and Nigeria show two diverging paths

- A decade of global decline in rule of law

- Case in point: Chile reverses the trend

- What comes next?

What drives long-term prosperity and where should reform begin? Data suggest that the rule of law consistently emerges as the most influential factor—outperforming economic and political freedom—in driving prosperity, not only enabling economic growth but also reinforcing political and market reforms.

Institutions are critical to development, yet they remain notoriously difficult to define and measure. Concepts like democracy, rule of law, or market economy are interpreted differently across different contexts, and scholarly debates frequently get mired in theory rather than grounded analysis.

To cut through this complexity, the Atlantic Council’s Freedom and Prosperity Center takes a pragmatic and functional approach. Instead of debating abstract definitions, we focus on how core institutional domains operate in practice, and how they shape a country’s trajectory.

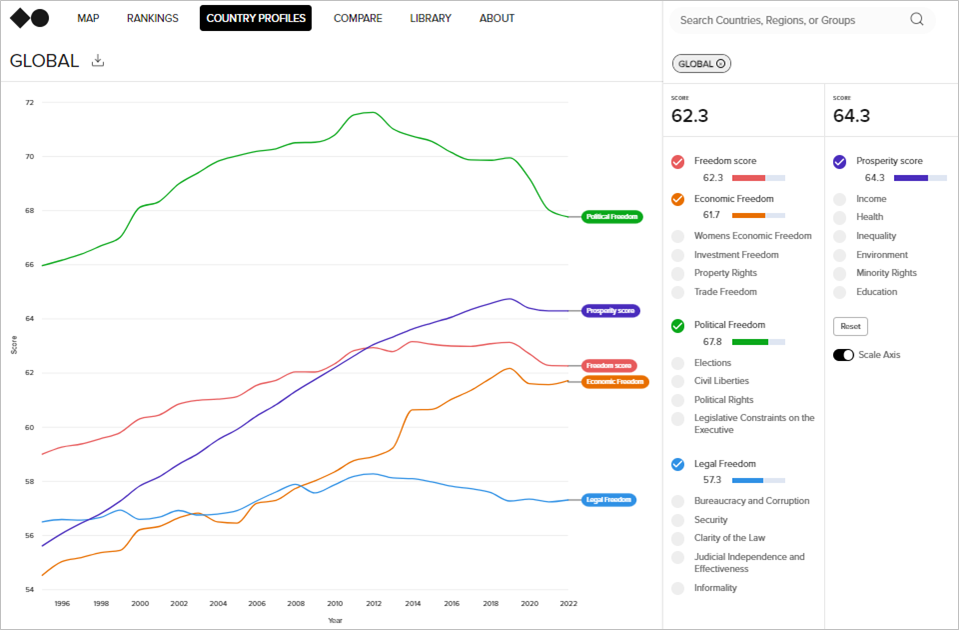

The Freedom Index developed by the Atlantic Council’s Freedom and Prosperity Center offers a clear framework to do just that. It rests on the idea that a country’s institutional foundation is made up of three interrelated domains: political, legal, and economic. These domains can be empirically assessed through the degree of freedom they confer on individuals and enterprises.

Each pillar of the Index captures a distinct facet of institutional quality:

- the political subindex evaluates how executive authority is attained and constrained;

- the legal subindex examines the rule of law, that is, the adherence to laws by both citizens and public officials; and

- the economic subindex assesses the extent to which markets, rather than the state, allocate resources.

Each is given equal weight to constitute the Freedom Index.

What sets the Freedom Index apart is its methodological clarity and empirical breadth. It translates complex institutional arrangements into measurable components, generating scores for 164 countries from 1995 to 2024. This allows a deeper examination of how each pillar—economic, political, and legal—functions in practice and influences a country’s long-term development and prosperity.

The Freedom and Prosperity Center’s research aims to investigate the relative impact of different institutional pillars and how they interact over time. While the rule of law emerges as the most influential factor, durable prosperity depends on the strength and interplay of all three institutional pillars—political, legal, and economic. The data simply offer indications of where reform efforts should begin, especially in contexts where progress must be sequenced or prioritized.

Rule of law is the strongest driver of prosperity

What do the most prosperous countries have in common? The data are clear: The rule of law is the strongest institutional driver of prosperity. It outperforms both political and economic freedom as a predictor of a country’s overall wellbeing.

Table 1. Rule of law shows the strongest correlation with overall prosperity

The rule of law then appears pivotal for building a stable, just, and prosperous society. It ensures that everyone, including and especially those in power, is subject to and accountable under the law. By having a robust and trusted rule of law, citizens have a framework so that when disputes occur, they know the system will ensure adequate protections. This not only ensures individual’s rights are protected by the law but also fosters economic development. Having environment where the rule of law is predictable and stable encourages more investment, innovation, and durable growth.

Its impact goes beyond economic growth. Across most dimensions of prosperity—such as income levels, life expectancy, and the treatment of minorities—the rule of law exerts the strongest and most consistent influence, and stands out as the dominant factor overall.

Figure 1. The rule of law shows the strongest correlation to most indicators of prosperity

The rule of law is an enabler of political and economic reforms

The rule of law might not only support prosperity but also underpin progress in other institutional domains. When we examine pairwise correlations between the rule of law, economic freedom, and political freedom, we find that both economic and political freedom correlate most strongly with the legal foundation provided by the rule of law. This indicates that the rule of law may serve as an enabler of democratic governance and market reforms.

Table 2. The rule of law correlates strongly with economic and political freedom

Case in point: Rwanda and Nigeria show two diverging paths

In 1995, Rwanda and Nigeria had nearly identical scores on the Freedom Index score, which averages countries’ performance across the three pillars: the rule of law, economic freedom, and political freedom. Over the next three decades, both countries made substantial progress, reaching similar overall levels by 2024.

However, the composition of their gains differed significantly. Rwanda’s improvement was driven by steady advances in the rule of law and economic freedom, while levels of political freedom remained largely unchanged. In contrast, Nigeria’s rise was largely the result of a sharp increase in political freedom following its transition from a military autocracy to a civilian-led democracy in 1999, with limited and inconsistent progress in legal and economic institutions.

Figure 2. Rwanda focused on rule of law and market reforms, whereas Nigeria led with political liberalization

These divergent experiences reflect two distinct models of institutional development. Rwanda followed a path that prioritized stability, legal order, and economic liberalization, while limiting political pluralism. This approach resembles the pre-democratic phases of South Korea and Spain, where legal and economic modernization preceded political opening. Nigeria, by contrast, pursued a “democratization first” model, mirroring the trajectory of many Latin American countries during the third wave of democratization at the end of the last century, where political liberalization outpaced improvements in state capacity and market openness.

While Rwanda’s case is of course unique because of the 1994 genocide, the continued restrictions on political freedom may be holding back its full potential. In the aftermath of 1994’s events, the country focused on restoring security, rebuilding legal institutions, and reconstructing the economic landscape. These efforts have produced impressive gains in prosperity. The outcome is measurable: Between 1995 and 2024, Rwanda’s Prosperity Index score increased by 19 points (out of 100), while Nigeria’s rose by almost 13 points.

However, despite these successes, Rwanda has yet to make the leap to full democratization, unlike South Korea and Spain, which transitioned to democracy and reaped long-term economic dividends. Rwanda’s gains were more stable and broad-based, but its long-term trajectory may depend on whether it embraces the political freedom reforms that historically accompany and reinforce sustained prosperity. In fact, according to our 2025 Freedom and Prosperity Indexes: How political freedom drives growth, democratizing countries see an average 8.8 percent boost in gross domestic product (GDP) per capita over twenty years compared to those that remain authoritarian.

Nigeria offers a striking example of political liberalization that has not been matched by corresponding advances in legal and economic institutional reforms. Following Nigeria’s transition to democratic governance in 1999, the country has seen significant improvement in the early years. However, in the past ten years, the country has seen a decline in political freedom, though the level remains higher than in 1999. Much of the improvement has encountered challenges, as improvement of political freedom has not been accompanied by continuous process in economic liberalization and building strong rule of law system.

Economic liberalization has been inconsistent and sector-specific. While sectors such as telecommunications and banking have undergone meaningful reforms, erratic trade policies, and persistent uncertainty in the oil sector have hindered the development of a balanced market economy.

Meanwhile, legal institutions continue to underperform, hampered by corruption, bureaucratic inefficiency, and insecurity. For nearly three decades, Nigeria’s score on bureaucracy and corruption has remained below the regional average, ranking 133 out of 164 countries. Politically motivated violence and instability, measured in our security component, are even more troubling, with Nigeria ranking 151 out of 164. Weak rule of law and politicized institutions have enabled rent-seeking elites to control the political landscape, carving out electoral integrity and public trust.

Nigeria has made undeniable progress in political freedom, but without stable market frameworks and a robust legal foundation, the country’s overall development trajectory remains constrained.

A decade of global decline in rule of law

Despite its critical role, the rule of law has been in global decline for more than a decade. Rule of law scores have dropped for eleven consecutive years, bringing the world to a seventeen-year low.

No country is immune to institutional erosion, and even societies long thought to be anchored in the rule of law are experiencing significant setbacks.

This trend affects all five legal components: clarity of the law, judicial independence and effectiveness, security, informality, and bureaucracy and corruption. Among them, clarity of the law has seen the steepest drop.

Strikingly, the steepest declines occurred in OECD countries (members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), those with the highest incomes and strongest historical rule of law traditions. While their absolute scores remain higher than non-OECD countries, the rate of deterioration is greater.

Figure 3. OECD countries have seen a steeper decline in four of the five components of rule of law

Clarity of the law has seen the sharpest decline among all components in both OECD and non-OECD groups, with a drop of 6.6 points in OECD countries and 2.7 points in non-OECD countries. However, when examining individual countries instead of group averages, the decline is more uneven in non-OECD countries. The top decliners among non-OECD countries have seen steeper individual drops. In contrast, although the average decline is greater among OECD countries, their top decliners in the group did not fall as drastically.

Among the OECD countries, the United Kingdom (-18.20), South Korea (-18), Canada (-17.70), Mexico (-16.80), and France (-14.60) saw the biggest decline in the factors that make up the “clarity of the law” measure. Among the non-OECD countries, top decliners include Nicaragua (-35.60), Afghanistan (-33.50), El Salvador (-26.30), Myanmar (-24.60), and Benin (-24.50).

Clarity of the law measures whether legal systems are consistent, public, non-contradictory, and predictably enforced. A decline indicates that countries are enacting laws that are less consistent within their legal systems. This also suggests that laws are applied more unevenly and less predictably due to the inconsistent nature of the change.

Case in point: Chile reverses the trend

Chile’s recent experience illustrates both the risks of institutional decline and the potential for recovery through public mobilization and legal reform. The period of social unrest from 2019 to 2022 (known in Chile as the estallido social, the “social outburst”) saw widespread protests over the cost of living, inequal access to education and healthcare, and perceived institutional shortcomings. In response, the government imposed states of emergency, restricted freedom of movement and assembly, and faced criticism for police violence. This period coincided with a significant drop in Chile’s “clarity of the law” score, reflecting public uncertainty over legal norms, emergency measures, and the consistency of law enforcement.

Amid these challenges, Chile undertook substantial efforts to address institutional weaknesses. At the end of 2019, political parties signed the “Agreement for Peace and a New Constitution” (Acuerdo por la Paz Social y la Nueva Constitución). It marked the official political commitment to begin a constitutional reform process to rebuild public trust and update legal frameworks. Although the new constitutional proposals were ultimately rejected in two referenda (2022 and 2023), the process itself broadened public engagement and debate on rule of law issues. Complementing these efforts, Chile enacted a major Economic Crimes Law in 2023, introducing stronger measures for corporate accountability and anti-corruption enforcement.

Figure 4. Chile’s rule of law (legal subindex) fell sharply in 2019 but has since improved, driven by constitutional and legal reforms

As a result of these initiatives, Chile has seen recovery in key aspects of the rule of law, particularly regarding legal clarity and accountability. The country demonstrates that targeted legal reforms and sustained civil society engagement can help stabilize institutional performance after a period of decline. Yet, ongoing political polarization and debates over institutional legitimacy remain, highlighting that recovery is often incremental rather than absolute. Chile’s case underscores both the vulnerabilities and resilience of rule of law institutions in the face of social and political upheaval.

What comes next?

The thirtieth year of the Freedom and Prosperity Indexes presents an urgent signal: The rule of law, foundational to prosperity and stability, is at its lowest point in nearly two decades. The data point to an uncomfortable reality: Even the most established democracies are not immune to institutional erosion, as setbacks to the rule of law could be seen worldwide.

This decline is not merely a legal or academic concern.

When the rule of law falters, the consequences are felt across every sector: Investors lose confidence, entrepreneurship stalls, corruption and informality expand, and trust weakens.

As these findings show, rule-of-law deterioration undercuts the effectiveness of political and economic reforms, stalling development and undermining the prospects for shared prosperity.

Yet that decline is not inevitable or irreversible. With sustained public pressure, civil society mobilization, and strategic government action, countries can recover lost ground and rebuild legal institutions, even after deep crises or periods of instability. Reform is rarely linear, and gains can be fragile, but targeted interventions have demonstrated real impact.

To reverse the downward trend and lay the groundwork for renewed prosperity, the following priorities are essential.

For governments:

- Make rule-of-law reform a strategic priority, not just a technocratic fix. Legal clarity, equal application of the law, and independent enforcement should be core to all reform agendas.

- Invest in judicial independence and capacity, including transparent appointments, adequate resources, and training to resist political interference.

- Combat informality and corruption by making formal participation more accessible, leveraging digital tools, and streamlining bureaucratic processes.

- Build legitimacy and trust by engaging citizens in legal and constitutional reforms, and by strengthening accountability mechanisms for public officials.

For donors and international financial institutions:

- Link aid and concessional finance to measurable improvements in rule of law and judicial effectiveness, rather than just outputs or legislative changes.

- Prioritize partnerships with countries that appreciate the importance of rule of law reforms for their own benefit.

- Support local civil society and independent media to foster public demand for legal reforms and hold institutions accountable.

- Prioritize justice sector and anti-corruption programming as core elements of economic development support, not afterthoughts.

For the private sector and investors:

- Champion transparency in contracts and dispute resolution to build market confidence.

- Collaborate with governments and reformers to develop and promote best practices in regulatory governance, compliance, and legal predictability.

- Advocate for stable and predictable legal environments, recognizing that long-term returns depend on the health of underlying institutions.

Ultimately, unlocking prosperity requires more than piecemeal reforms or technical fixes. It demands a strategic and coordinated effort to strengthen all pillars of institutional quality—political, legal, and economic—with special attention to the enabling power of the rule of law. By learning from three decades of global data and country experiences, policymakers and stakeholders can sequence reforms, prioritize the most impactful interventions, and build resilience against future shocks.

Political liberalization can act as a powerful catalyst for progress, especially when it helps correct institutional deficits. At the same time, the impact of democracy on growth is not automatic or immediate; it depends on timing, national conditions, and the broader institutional environment. This underscores a central insight of the Freedom and Prosperity Indexes: that freedom, when exercised in its full political, legal, and economic dimensions—is not just a moral imperative, but a pragmatic path to shared prosperity.

Explore the data

The Freedom and Prosperity Indexes rank 164 countries around the world according to their levels of freedom and prosperity. Use our award-winning site to explore twenty-nine years of data, compare countries and regions, and examine the sub-indexes and indicators that comprise our indexes.

About the authors

Related content

Stay Updated

Get the latest program developments, reports & research, and events.

Explore the program

The Freedom and Prosperity Center aims to increase the prosperity of the poor and marginalized in developing countries and to explore the nature of the relationship between freedom and prosperity in both developing and developed nations.

Image: IMAGO/Alexander Limbach via Reuters Connect