The geopolitical trends shaping the EU’s policies on China

This is the first chapter of the report “Is Europe waking up to the China challenge? How geopolitics are reshaping EU and transatlantic strategy.” Read the full report here.

China’s global ambitions, unfolding in an era of renewed great-power competition, pose significant challenges to the core interests of the United States and its Western allies—and have placed Beijing at the center of the transatlantic economic and security agenda. In the 1990s and early 2000s, the United States, the European Union (EU), and EU member states largely assumed that engagement with China would be mutually beneficial, with economic integration encouraging Beijing to align with the global rules-based order. Over time, that assumption has collapsed. Instead, both the United States and the EU increasingly regard China not just as a competitor but as a strategic rival and systemic challenger—a country determined to promote a model fundamentally at odds with Western principles of liberal democracy and market economy and to reshape the international order in its favor.1Valbona Zeneli, “The Trends Driving Transatlantic Convergence on China,” Diplomat, November 30, 2023, https://thediplomat.com/2023/11/the-trends-driving-transatlantic-convergence-on-china/.

The United States was the first to make this decisive strategic shift. In its 2017 National Security Strategy (NSS), the first Trump administration formally redefined China as a “strategic competitor” and a “once-in-a-generation challenge.”2The White House. 2017. National Security Strategy of the United States of America. Washington, DC: The White House. https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NSS-Final-12-18-2017-0905.pdf. The Biden administration reaffirmed this stance in its 2022 NSS, noting that China “harbors the intention, and increasingly, the capacity to reshape the international order in favor of one that tilts the global playing field to its benefit.” Yet the focus on competition with China—and on the strategic importance of Asia—predates both US President Donald Trump and US President Joe Biden. The Obama administration’s “pivot to Asia” had already acknowledged China’s rising economic and strategic significance, with particular attention to the Indo-Pacific region.3Hillary Clinton. 2011. “America’s Pacific Century.” Foreign Policy, no. 189 (November): 56–63. https://foreignpolicy.com/2011/10/11/americas-pacific-century/.

Europe’s recognition of the China challenge came more slowly. For decades, the EU approached Beijing primarily as an economic partner. The first major trade agreement between the EU and China in 1985, the initiation of annual EU-China summits in 1998, and European support for China’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 all reflected the belief that trade would encourage cooperation. Even the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989, which temporarily froze political ties and prompted an arms embargo, did not fundamentally alter the EU’s long-term calculus. It was only in March 2019 that the EU formally adopted a more skeptical stance, describing China as “simultaneously . . . a cooperation partner with whom the EU has closely aligned objectives . . . an economic competitor in the pursuit of technological leadership, and a systemic rival promoting alternative models of governance.”4“EU-China—A Strategic Outlook,” European Union, March 12, 2019, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=JOIN%3A2019%3A5%3AFIN.

The EU’s growing skepticism of China has been driven by a series of shocks and geopolitical trends that have fundamentally reshaped how policymakers in Brussels and across member states view Beijing.5Zeneli, “The Trends Driving Transatlantic Convergence on China”; Zoltán Fehér, “Xi Jinping Visited Europe to Divide It. What Happens Next Could Determine If He Succeeds,” Atlantic Council, June 1, 2024, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/xi-jinping-visited-europe-to-divide-it-what-happens-next-could-determine-if-he-succeeds/. These trends include:

- US-China strategic competition;

- Uncertainty about continued US engagement globally and in Europe;

- Russia’s war on Ukraine, backed by China; and

- China’s economic and competitiveness challenges to the EU.

A deeper understanding of these trends—the geopolitical pressures shaping Europe, the continent’s mounting sense of vulnerability, and the strategic responses they generate—can enable US policymakers to tailor outreach, design joint initiatives, and strengthen a unified transatlantic agenda to address the China challenge. Yet US officials often lack sufficient insight into how these dynamics influence EU decision-making. This report aims to bridge that gap.

To that end, it analyzes the four geopolitical trends in detail, assesses their impact on the EU’s and its member-states’ China policies—particularly across trade and investment, technology, and security—and offers recommendations to help US policymakers use this understanding to reinforce transatlantic coordination. After all, the United States can prevail in its strategic competition with China only by working in concert with its allies—especially the EU, Beijing’s second-largest trading partner.

1. US-China strategic competition

China’s expansionist global posture—and the resulting revival of great-power competition in the international system, most clearly manifested in US-China rivalry—has significantly reshaped European thinking about its role in the world. China’s increasingly assertive efforts to shape the international order to accommodate its authoritarian model have put it at odds with the EU and the United States.

This development is, in part, a result of a strategic US effort to integrate China into the international order and encourage liberalization through a long-standing engagement strategy following the end of the Cold War. Successive administrations maintained this approach despite mounting evidence that China was not integrating and was instead emerging as a challenger. By overlooking this reality, the United States facilitated China’s rise, effectively creating a peer competitor for itself and for Europe.

The first US president to recognize the failure of engagement and reframe China as a strategic competitor was Donald Trump during his first term.6Zoltán Fehér. “The Rise and Fall of U.S. Engagement toward China,” Fletcher Center for Strategic Studies, August 17, 2020, https://sites.tufts.edu/css/?p=1198. His policy shift reflected a broader bipartisan consensus in Washington to place strategic competition at the center of US grand strategy. Although adopting a different tone and emphasizing coordination with allies, the Biden administration upheld key elements of Trump’s China strategy, including trade restrictions, technology controls, and political and military efforts to counter China’s global influence.7Zoltán Fehér, “Realism, Liberalism, and Strategic Competition: The Grand Strategy of the United States during the Biden Administration,” Foreign Policy Review [Külügyi Szemle—Hungary] 22, 4 (2023), 28–44, https://hiia.hu/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/3-Feher-Zoltan.pdf. Although the second Trump administration is expected to continue the balancing strategy initiated during Trump’s first term, it has not yet articulated a clear strategy vis-à-vis China, oscillating between a balancing posture and a cooperative approach aimed at negotiating a “grand deal” with Beijing.

These mixed signals have made it harder for the EU and its member states to align with the United States’ stance on China—or to formulate their own strategy in response. Europe has consistently sought to avoid being drawn into a binary competition between the two superpowers. While recognizing the systemic challenges posed by Beijing’s global ambitions, it seeks to protect both its economic interests and strategic autonomy. However, mounting US-China competition is forcing the EU and European countries to pick a side.

2. Uncertainty over US engagement globally and in Europe

In the 2010s, the United States—the EU’s most important global ally—entered an era of heightened domestic polarization and international retrenchment. The rise of radicalism and populism in both major political parties, along with Trump’s election victories in 2016 and 2024, dramatically reshaped the political landscape. This period saw declining bipartisanship, rising identity politics and personal attacks, and the growing influence of radical and extremist forces.

Internationally, the Obama administration began retrenching the United States from its global leadership role, including reducing its presence and influence in Europe. US President Barack Obama’s strategic “pivot to Asia” signaled that the United States would shift its focus and resources away from Europe and the Middle East toward the Indo-Pacific. The first Trump administration accelerated this retrenchment, weakening US alliances and withdrawing from several multilateral institutions that previous US administrations had helped build after World War II. Europe was particularly affected, as Trump called US security guarantees into question—a concern magnified by the Ukraine war, which further exposed the continent’s dependence on the United States as a security provider.

While the Biden administration sought to restore US global leadership, mend alliances, and strengthen multilateralism, the forces driving retrenchment remain influential among both the US public and political elite, as evidenced by Trump’s second election victory. As a result, European citizens and leaders remain uncertain whether the United States will sustain its global leadership role and its position as guarantor of European security over the long term.

Continuing and accelerating these trends, the second Trump administration has rapidly scaled back US engagement, questioned support for Ukraine, pursued rapprochement with Russia, and imposed tariffs on EU exports. These moves have deepened political, economic, and security rifts between Washington and Brussels, prompting a strategic reassessment in Europe. While the United States eventually signed a trade deal with the EU in July, tensions over EU auto exports and Trump’s openness to engaging with Russian President Vladimir Putin continue to strain relations.

As a result of this transatlantic rift, some European leaders have called for a pragmatic reset and closer engagement with China, while others caution that China’s structural economic and political challenges make any “grand deal” unrealistic. The latter group argues that transatlantic cooperation remains the best path forward. Reflecting this stance, many EU representatives emphasized at the 2025 EU-China Summit that closer ties with Beijing would require China to change its behavior, end unfair trade practices, and cease actions that undermine the EU’s core interests.

3. Russia’s war on Ukraine—backed by China

While uncertainty about US global engagement has shaken Europe’s confidence in having a strong ally and external guarantor of security and the liberal international order, Russia’s war on Ukraine has shattered the European sense of physical security. Moscow’s aggression posed a direct challenge to the Western global order and the values underpinning it—international peace and security, national self-determination, representative government, and fundamental human rights. For Europeans, the war has demonstrated that an aggressor state exists in their immediate neighborhood, threatening democracy, the European way of life, and the continent’s security architecture.

At the same time, Beijing’s support for Russia’s war served as a further wake-up call for European policymakers. After recognizing China as a supporter and enabler of Russian aggression against Ukraine, Europe’s perception of Beijing shifted. European countries began to view China both as a security threat and as a liability in other areas, including critical infrastructure. In this sense, Russia’s war has exposed Europe’s vulnerabilities not only toward Moscow but also toward Beijing, highlighted its limited capabilities in countering its adversaries, and underscored the continued importance of US military assistance for European security.

Initially, the Ukraine war and China’s support for Russia unified the United States and the EU at a level unprecedented since the end of the Cold War. Under the Biden administration, the transatlantic partners supported Ukraine’s fight for independence and territorial integrity and sanctioned both Russia and China. During the first three years of the war, European narratives, attitudes, and policies on China continued to shift significantly—though unevenly across member states and EU institutions—increasingly converging with US approaches and positions.

However, the second Trump administration’s upending of transatlantic relations, combined with its tendency to favor Russia at times in negotiations over the Ukraine war, has created a deep divide between the United States and Europe. European leaders have made significant efforts to bridge this divide and revive transatlantic unity on Ukraine, with some success in the weeks following the August 2025 White House multilateral meeting on Ukraine. Many EU policymakers continue to view Beijing as a systemic rival posing long-term risks to European security and democratic values, while others are more open to strategic engagement, advocating a recalibration of EU-China relations. Nevertheless, from a European perspective, China’s continued support for Russia’s war remains a major obstacle to easing tensions.

4. China’s economic and competitiveness challenges to the EU

A crucial aspect of China’s global expansion has been its economic and technological pressure on the EU and its economic security. The Chinese economy has become more state-driven, with Chinese leaders increasingly disavowing Western liberal values.8Michael Beckley and Hal Brands, “China’s Threat to Global Democracy,” Journal of Democracy, December 2022, https://www.journalofdemocracy.org/chinas-threat-to-global-democracy/. The rapid pace of China’s transformation and its advances in technological capabilities are unprecedented. Unfair business practices, state subsidies, forced or illegal technology transfers, economic coercion, and limited market access have negatively affected the US and EU economies. More recently, China has sought to ease its domestic economic struggles by dumping industrial overcapacity onto the European market and relocating some production to the EU and its periphery, threatening key sectors such as renewable energy and electric vehicles (EVs).9Esther Goreichy, Jacob Gunter, and Grzegorz Stec, “China’s Overcapacity and the EU + German China Policy under Merz + EU-China Trade,” Mercator Institute for China Studies, May 16, 2025, https://merics.org/en/merics-briefs/chinas-overcapacity-and-eu-german-china-policy-under-merz-eu-china-trade.

In response, the European Commission, under President Ursula von der Leyen, has outlined an economic security agenda that goes further than some member states have been willing to embrace.10Jörn Fleck, et al., “The ‘De-risk’ Is in the Details: A Look at Europe’s Ambitious New Economic Security Strategy,” Atlantic Council, June 22, 2023, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/experts-react/the-de-risk-is-in-the-details-a-look-at-europes-ambitious-new-economic-security-strategy/. Some countries have opposed this strategic shift because their economies are more open and trade-dependent—and therefore more exposed to China, particularly given that China is Europe’s largest source of imports at 21 percent and its third-largest export market at 8 percent. A major sign of the relative success of the Commission’s agenda—and its transatlantic relevance—has been that the terminology of “de-risking” has entered the transatlantic mainstream.

At the same time, the EU has been less aggressive in dealing with China than the United States. While the latter has rolled out more ambitious measures to restrict Chinese access to technology and investment, the EU has expanded its policy toolbox to counter Beijing’s distortive economic practices—through the EU Foreign Subsidies Regulation and its new Anti-Coercion Instrument, for instance—without explicitly identifying Beijing as the target.

Where the Commission has taken action, such as in its anti-subsidy investigation into Chinese EV imports, significant disagreements and pushback have arisen among member states, depending on how severely they are affected. These dynamics frequently leave room for skepticism or misunderstanding among US policymakers regarding the strengths and weaknesses of Europe’s strategies and their implementation.

In his 2024 report on European competitiveness, former President of the European Central Bank Mario Draghi highlighted the urgency of investing between €750 billion and €800 billion annually in innovation, artificial intelligence, and clean energy, while streamlining regulations and advancing a coordinated industrial policy to bolster the EU’s long-term economic resilience and strategic autonomy. Ironically, Europeans continue to rely on Chinese technology in areas where the EU still lags. The most pressing challenge remains the widening gap between policymakers’ security concerns and European industry actors’ vested economic interests in the Chinese market.

About the author

Related content

Explore the programs

The Global China Hub tracks Beijing’s actions and their global impacts, assessing China’s rise from multiple angles and identifying emerging China policy challenges. The Hub leverages its network of China experts around the world to generate actionable recommendations for policymakers in Washington and beyond.

The Europe Center promotes leadership, strategies, and analysis to ensure a strong, ambitious, and forward-looking transatlantic relationship.

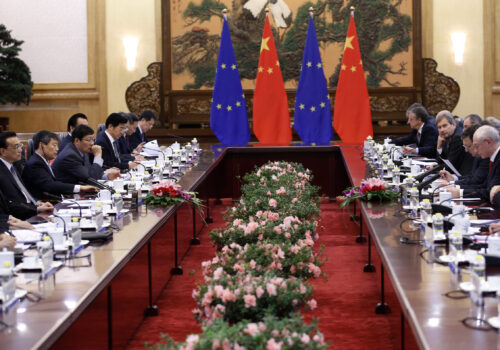

Image: A view inside the Great Hall of the People is seen on a camera screen before the second plenary session of the National People's Congress (NPC) at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, China, March 9, 2016. REUTERS/Kim Kyung-hoon.