WASHINGTON—US President Donald Trump shocked—and re-shocked—the global economy in 2025, but growth powered through. Thanks to the surge in artificial-intelligence (AI) investment and limited inflation from tariffs, it’s clear that many economists’ doomsday predictions never materialized.

By the end of 2025, forecasts across Wall Street predicted “all-time highs” for the S&P 500 in 2026. Many investors believe that the AI train won’t slow down, central banks will continue cutting rates, and US tariffs will cool down in a midterm year.

But markets may be confusing resilience for immunity.

The reality is that several daunting challenges lie ahead in 2026. Advanced economies are piling up the highest debt levels in a century, with many showing little appetite for fiscal restraint. At the same time, protectionism is surging, not just in the United States but around the world. And lurking in the background is a tenuous détente between the United States and China.

It’s a dangerous mix, one that markets feel far too comfortable overlooking.

Here are five overlooked trends that will matter for the global economy in 2026.

The real AI bubble

Throughout 2025, stocks of Chinese tech companies listed in Hong Kong skyrocketed. For example, the Chinese chipmaker Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (known as SMIC) briefly hit gains of 200 percent in October, compared to 2024. The data shows that the AI boom has become global.

Everyone has been talking about the flip side of an AI surge, including the risk of an AI bubble popping in the United States. But that doesn’t seem to concern Beijing. Alibaba recently announced a $52 billion investment in AI over the next three years. Compare that with a single project led by OpenAI, which is planning to invest $500 billion over the next four years. So the Chinese commitment to AI isn’t all-encompassing for their economy.

Of course, much of the excitement around Chinese tech—and the confidence in its AI development—was driven this past year by the January 2025 release of the DeepSeek-R1 reasoning model. Still, there is a limit to how much Beijing can capitalize on rising tech stocks to draw foreign investment back into China. There’s also the fact that 2024 was such a down year that a 2025 rebound was destined to look strong.

It’s worth looking at AI beyond the United States. If an AI bubble does burst or deflate in 2026, China may be insulated. It bears some similarities to what happened during the global financial crisis, when US and European banks suffered, but China’s banks, because of their lack of reliance on Western finance, emerged relatively unscathed.

The trade tango

In 2026, the most important signal on the future of the global trading order will come from abroad. US tariffs will continue to rise with added Section 232 tariffs on critical industries such as semiconductor equipment and critical minerals, but that’s predictable.

But it will be worth watching whether the other major economic players follow suit or stick with the open system of the past decades. As the United States imports less from China, but Chinese cheap exports continue to flow, will China’s other major export partners add tariffs? The answer is likely yes.

US imports from China decreased this past year, while imports by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and European Union (EU) increased. In ASEAN, trade agreements, rapid growth, and interconnected supply chains mean that imports from China will continue to flow uninhibited except for select critical industries.

But for the EU, 2025 is the only year when the bloc’s purchases of China’s exports do not closely resemble the United States’ purchases. In previous years, they moved in lockstep. In 2026, expect the EU to respond with higher tariffs on advanced manufacturing products and pharmaceuticals from China, since that would be the only way to protect the EU market.

The debtor’s dilemma

One of the biggest issues facing the global economy in 2026 is who owns public debt.

In the aftermaths of the global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic, the global economy needed a hero. Central banks swooped in to save the day and bought up public debt. Now, central banks are “unwinding,” or selling public debt, and resetting their balance sheets. While the US Federal Reserve and the Bank of England have indicated their intention to slow down the process, other big players, such as the Bank of Japan and the European Central Bank, are going to keep pushing forward with the unwinding in 2026. This begs the question: If central banks are not buying bonds, who will?

The answer is private investors. The shift will translate into yields higher than anyone, including Trump and US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, want. Ultimately, it is Treasury yields, rather than the Federal Reserve’s policy rate, that dictate the interest on mortgages. So while all eyes will be on the next Federal Reserve chair’s rate-cut plans, look instead at how the new chair—as well as counterparts in Europe, the United Kingdom, and Japan—handles the balance sheet.

Wallet wars

By mid-2026, nearly three-quarters of the Group of Twenty (G20) will have tokenized cross-border payment systems, providing a new way to move money between countries using digital tokens. Currently, when you send money internationally, it can go through multiple banks, with each taking a cut and adding delays. With tokenized rails, money is converted into digital tokens (like digital certificates representing real dollars or euros) that can move across borders much faster on modern digital networks.

As the map below shows, the fastest movers are outside the North Atlantic: China and India are going live with their systems, while Brazil, Russia, Australia, and others are building or testing tokenized cross-border rails.

That timing collides with the United States taking over the G20 presidency and attempting to refresh a set of technical objectives known among wonks as the “cross-border payments roadmap.” But instead of converging on a faster, shared system, finance ministers are now staring at a patchwork of competing networks—each tied to different currencies and political blocs.

Think of it like the 5G wars, in which the United States pushed to restrict Huawei’s expansion. But this one is coming for wallets instead of phones.

For China and the BRICS group of countries in particular, these cross-border payments platforms could also lend a hand in their de-dollarization strategies: new rails for trade, energy payments, and remittances that do not have to run through dollar-based correspondent banking. This could further erode the dollar’s international dominance.

The question facing the US Treasury and its G20 partners is whether they can still set common rules for this emerging architecture—or whether they will instead be forced to respond to fragmented alternatives, where non-dollar systems are already ahead of the game.

Big spenders

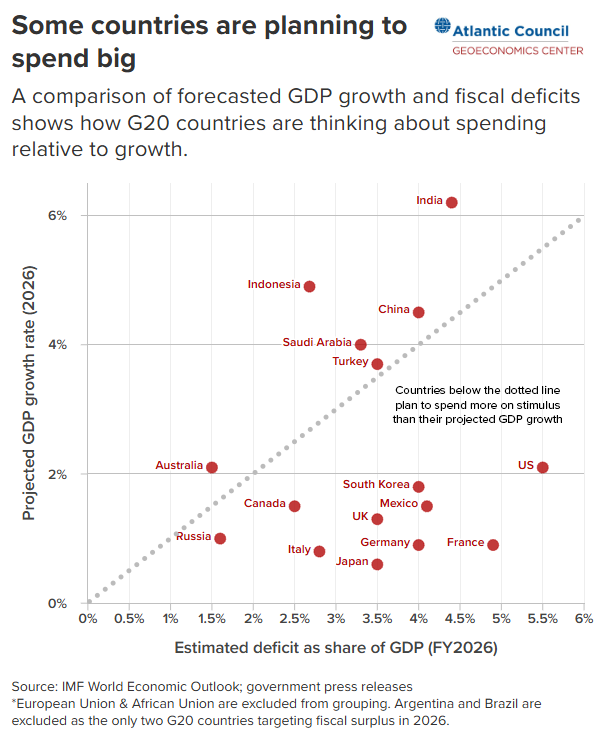

From Trump’s proposal to send two-thousand-dollar checks to US citizens (thanks to tariff revenue) to Germany’s aim to ramp up defense spending, major economies across the G20 have big plans for additional stimulus in 2026. That’s the case even though debt levels are already at record highs. Many countries are putting off the tough decisions until at least 2027.

This chart shows G20 countries with stimulus plans, comparing their projected gross domestic product (GDP) growth rates for 2026 with their estimated fiscal deficits as a percentage of GDP. It’s a rough metric, but it gives a sense of how countries are thinking about spending relative to growth and debt in the year ahead. Countries below the line are planning to loosen fiscal taps.

Of course, not all stimulus plans are created equal. Ottawa, for example, is spending more on defense and investments aimed at improving the competitiveness of the Canadian economy, while keeping its estimated fiscal deficit at around 1 percentage point of projected 2026 GDP growth. US growth isn’t bad, coming in at a little over 2 percent, but the government plans to run a fiscal deficit of at least 5.5 percent. Russia is attempting to prop up a wartime economy, while China is pursuing ambitious industrial policies and pushing off its local debt problems. And on China, while the chart above shows International Monetary Fund and other official estimates for China’s GDP growth, some economists, including ones from Rhodium Group, argue that China’s real GDP growth could be as low as 2.5 percent for 2026, which would push China below the line displayed.

Within this group, emerging economies are experiencing stronger growth and may have more room to run deficits next year. For advanced economies, that spending tradeoff is much harder to justify.

When Trump captured Nicolás Maduro on the first Saturday of the year, there was speculation that when markets opened the following Monday, they might react negatively given a possible geopolitical shock or positively in anticipation that new oil would be coming online. But markets were muted, and they took the news in stride. That has been the modus operandi of markets ever since Trump took office—trying to see past the immediate news and ask what actually matters for economic growth. In 2025, that strategy paid off. But 2026 may look very different.