In January, France relinquished its final military base in Chad, ending a historic partnership. Paris had long enjoyed an intimate relationship with Chad’s ruling class, and French troops had been deployed within the country almost continuously since it achieved independence.

France’s departure is indicative of a larger shift in the region. The Sahel’s geopolitics have changed dramatically in the last five years. Since 2020, military juntas have seized power in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger. They have gradually driven out thousands of Western troops, including troops from France, the European Union, and the United States. These troops were performing capacity-building missions and conducting counterterrorism operations. They have since been replaced, in large part, by Russian paramilitaries. The existing regional security architecture is in shambles, following Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger’s withdrawal from the G5 Sahel Joint Force and, more recently, from the Economic Community of West African States.

The Sahel is in the middle of a transformative process that has ushered in new leaders, military strategies, and foreign alliances. It is imperative that the United States rethink the bipartisan assumptions that have underwritten its Sahel policy. The region is experiencing profound change, and US policy must adapt accordingly.

Outdated assumptions, new realities

US policy toward the Sahel has rested on these four unspoken assumptions, all of which must be updated if Washington aims to help stabilize the region and improve its standing there.

1. Western allies’ involvement can achieve US regional security objectives.

For at least a decade, US policy has taken for granted that allies’ involvement in the Sahel would generate access, bolster influence, and help achieve US regional security objectives. This is evidenced by the fact that US resources were marshalled in support of partner-led efforts. Under Operation Juniper Micron, for example, which began in 2013 and lasted for roughly a decade, the US military provided logistical support, as well as intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance, to enable French operations in Mali. Most Western troops deployed within the Sahel were not American.

There is nothing wrong with burden sharing or deconfliction. These measures can eliminate redundancy, reduce the cost of defense engagement, and amplify operational effects. That said, it would be wrong to assume that ally involvement translates directly into US gains. Perceptions of foreign powers vary, and it is not clear that Western investment earns the United States any additional influence. In fact, aligning itself with France, an unpopular former colonial power, may have inadvertently harmed US interests. The United States has steadily lost soft power on the continent since 2021. After Niger’s junta expelled French troops, Washington hoped to avoid a similar fate. The US military ultimately failed to differentiate itself and withdrew.

Moreover, relying on allies to advance its security objectives exposes the United States to risks if its they depart. The United States had few options to address rising instability in Mali after French and European Union troops withdrew in 2022. The situation has only worsened in the years since. Mali is currently ranked third among the countries most impacted by terrorism. Terrorists attacked the capital city this fall, indicating that they are capable of operating in large portions of Mali’s territory. This could pose a threat to US interests, facilities, or personnel.

2. An “outside-in” approach can prevent the spread of instability beyond the Sahel.

US policy has also assumed that investments in defense, economic development, and good governance can prevent the spread of instability from the Sahel to coastal West Africa. Some experts contend that Washington should adopt an “outside-in” approach, shifting focus from the Sahel to its southern neighbors. Proponents of this approach argue that very little can be done to improve stability in the Sahel, and that the United States would be better served partnering with peripheral states to bolster their defenses. The “outside-in” approach involves dramatically increasing assistance to coastal West Africa while reducing US assistance to the Sahel.

To this end, US leaders emphasize the importance of the Global Fragility Act, a law passed in 2019 that provides funding to curb instability in Benin, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Guinea, and Togo, among others—but does not address its origins in the Sahel. If it is not addressed directly, however, Sahel-based instability is likely to intensify.

The data speaks for itself. Last year was the deadliest in the Sahel’s history. The effects of this instability are evident in the coastal states of Benin and Togo, where al-Qaeda-affiliated Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) has begun to consolidate its presence. Terrorist groups, especially JNIM, are poised to continue their push southward into coastal West Africa.

The “outside-in” approach rests on the assumption that, with sufficient assistance, coastal West African states can build institutional capacity faster than terrorists can expand operations southward. Unfortunately, there is limited evidence to support this claim.

3. States would forgo partnerships with US adversaries if they knew the consequences.

A third assumption embraces the idea that Sahel states would forgo partnerships with US adversaries if they appreciated the consequences. The United States has largely relied on messaging to dissuade states from expanding cooperation with its adversaries. US officials point out that the support offered by Washington’s adversaries is ineffective. “It’s self-evident that a Russian role, whether it’s Wagner or it has a GRU label, has not demonstrably improved the lives of Africans,” said Molly Phee, assistant secretary of state for African affairs, during an interview in March 2024. That same month, an interagency delegation cautioned Niger against deepening its ties to Russia and Iran.

Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger have all ignored these warnings, partnering with Russia on counterterrorism in the past few years. Their leaders are rational and likely aware of the potential consequences, but they faced a difficult choice. The United States is legally restricted from providing these states assistance, as each experienced a coup d’état. Sahel leaders were not persuaded by US messaging. Absent competing offers, and facing an acute threat, these leaders opted to pursue ineffective security assistance from US adversaries.

4. The loss of forward-deployed positions in Chad and Niger critically threatens the United States’ ability to achieve its regional security objectives.

Last year, officials warned that withdrawals from Chad and Niger would prevent the United States from achieving its security objectives in the region. “If we lose our footprint in the Sahel, that will degrade our ability to do active watching and warning, including for homeland defense,” said General Michael Langley, the commander of US forces in Africa. From Niger, the US military was able to monitor threats in neighboring countries, such as Libya and Mali.

Langley has a point. The US military must remain engaged in the Sahel if its goal is to provide strategic warning of threats to the United States. Proximity to the threat is important to this mission, but so are partnerships. The United States needs strong relationships with African partners, built on coordination, information sharing, and strategic access. In both Chad and Niger, the greatest loss was arguably that of willing and capable local partners.

The United States could still secure its vital national interests if it pursued light footprints and distributed security assistance across several African partner countries. This approach may also obviate the need for big base operations, offering a cost-effective and flexible solution.

What comes next

US policy options are constrained by the situation on the ground. The United States is legally restricted from providing certain forms of defense and development assistance to countries that experience military coups d’etat, a category that includes Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger. This presents challenges, but it does not mean the United States is entirely without options. US leaders must still assess whether the risks of inaction outweigh those of engagement, but, at the very least, this exercise should foster a more thoughtful, constructive debate on the issue.

The United States could still pursue legal, limited, and nonlethal security cooperation with these states. It could provide critical enablers, such as force protection, military medical assistance, or logistical support. It could provide training on how to respond to improvised explosive devices or deliver humanitarian aid. Assistance could gradually be expanded if these states move toward democratic governance, reduce extrajudicial killings, and enhance military accountability—or curtailed if they fail to do so. The best way for the United States to promote regional stability and credibly compete against its adversaries is to address Sahel countries’ security concerns.

Finally, while maintaining investments in the Sahel, the United States could focus on building partner capacity in coastal West Africa. The “outside-in” approach constructs a false dichotomy, in which US policy can prioritize either the Sahel or coastal West Africa. The two regions are inextricably linked, and instability in one inevitably threatens the other. Investing in both affords the United States the greatest opportunity to prevent terrorism’s spread and secure its own interests.

The challenges facing the Sahel are immense, but they are not insurmountable. By reevaluating long-held assumptions and adapting policy to the rapidly changing geopolitical environment, the United States can play a vital role in the region. Amid adversaries’ encroachment and terrorist groups’ expansion, the United States must adjust its approach to maintain its relevance and protect its interests. There are opportunities to do so, but success will depend on a willingness to pursue new policies, with a clear-eyed consideration of the risks and rewards that lie ahead.

Jordanna Yochai is a defense analyst, whose portfolio includes the West African Sahel. She is currently on leave from the US Department of Defense, pursuing a master’s degree at Columbia University’s School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA).

The positions expressed in this article do not reflect the official position of the US Department of Defense. The US Department of Defense does not endorse the views expressed in hyperlinked articles or websites, including any information, products, or services contained therein.

The Africa Center works to promote dynamic geopolitical partnerships with African states and to redirect US and European policy priorities toward strengthening security and bolstering economic growth and prosperity on the continent.

Further reading

Thu, Mar 13, 2025

What airstrikes in Somalia show about the war on terror

AfricaSource By Alexander Tripp

With terrorist groups increasingly prevalent throughout Africa, the United States is likely to devote more attention to counterterrorism efforts on the continent.

Tue, Feb 25, 2025

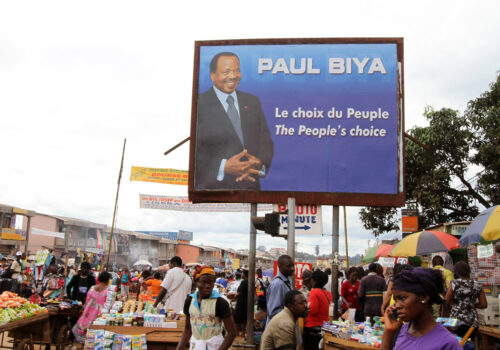

Cameroon may soon lurch into crisis. Here’s how the US can help steer it away.

AfricaSource By Benjamin Mossberg

Benjamin Mossberg outlines ten recommendations for elevating Cameroon on the US foreign policy agenda.

Mon, Feb 24, 2025

Trump’s dismantling of USAID offers a new beginning for Africa

AfricaSource By Rama Yade

African leaders should take advantage of the dismantling of USAID to propose new partnerships made up of direct investment and fairer trade, Rama Yade writes.

Image: A French fighter jet prepares to take off, as France starts the withdrawal of its military from Chad with the departure of two warplanes, in N'Djamena, Chad, December 10, 2024. REUTERS/Stringer.