Italians go to the polls on March 4th to elect a new government. Under a new electoral system, the outcome is uncertain. The Global Business and Economics program looks at some key economic indicators that could influence the election.

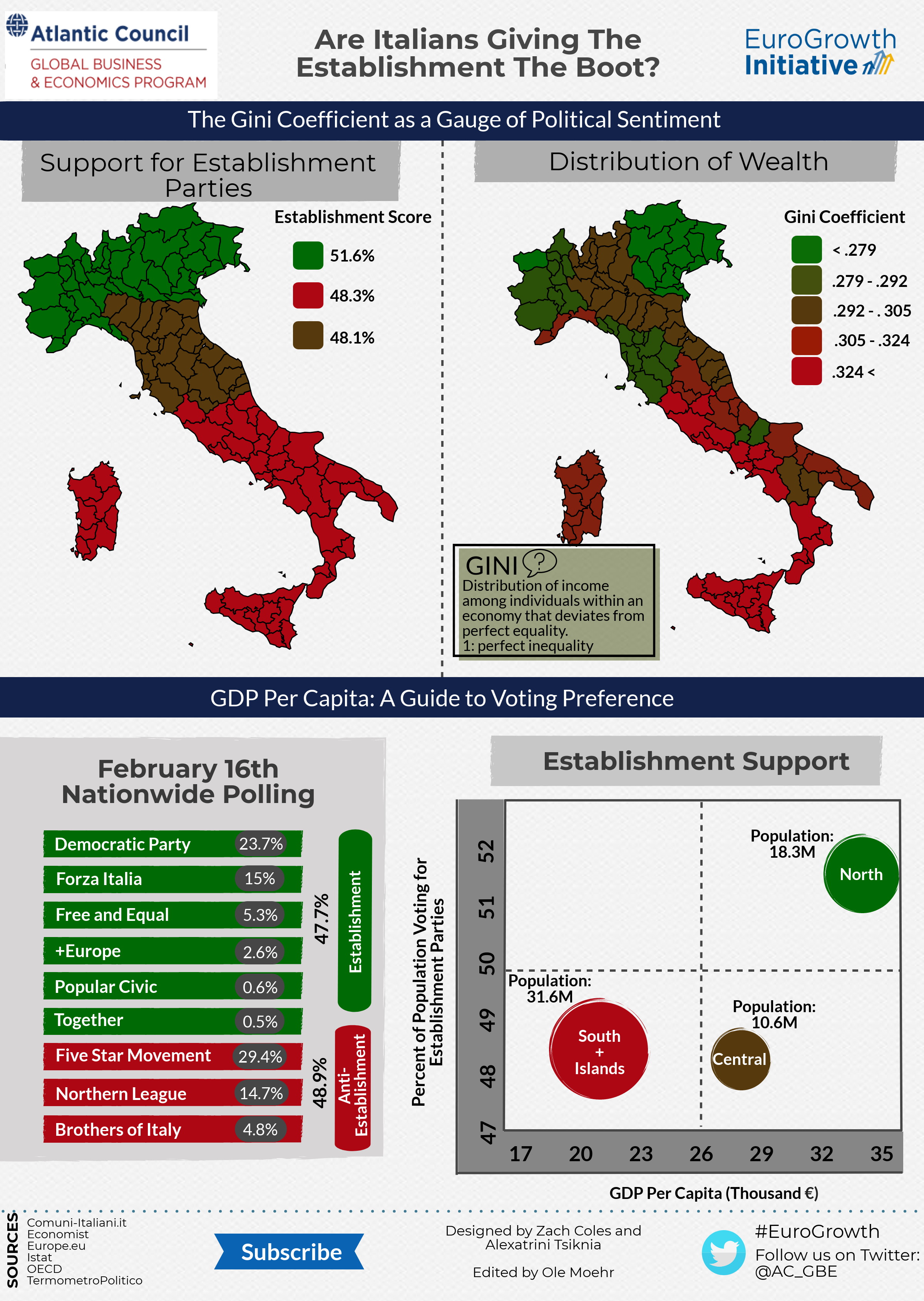

On March 4, Italy will hold highly-anticipated national elections that are also an important test for the country’s newly established electoral system. Following a failed referendum and Prime Minister Renzi’s resignation in 2016, a caretaker government is in place until the upcoming elections. The redesigned system incentivizes coalition building, as only a party that reaches 40% percent of the vote is given 50% of the seats. The rest of the seats are awarded in a proportional fashion. At the same time, Italy, much like the rest of the Western hemisphere, is experiencing a rise in anti-establishment political sentiment, with northern regions showing the highest approval for establishment parties while the central and southern parts of Italy favor anti-establishment political forces. In this blog post, we assess the political sentiment in Italy through the lenses of the Gini coefficient and gross domestic product (GDP) per capita.

The rise of anti-establishment parties is evident in the latest election polls. The Five Star Movement, along with the Northern League and Brothers of Italy are Italy’s three rising anti-establishment forces, with political agendas focused on anti-immigration, Euro-skepticism, tax relief, and even universal basic income for lower income Italians. Establishment, pro-EU parties on the other hand, such as the Democratic Party and former Prime Minister Berlusconi’s Forza Italia, have substantially shrunk in popularity, with the Democratic Party only coming in second in the polls and Forza third, tied with the Northern League. By analyzing regional party poll data, we created an “Establishment Score” for Italy’s northern, central, and southern regions, depicting the percentage of the population supporting pro-establishment parties in each region.

Italy is recovering slowly from its double-dip recession. Wage growth has remained below one percent in the last two years and youth unemployment was still a staggering 37.8 percent as of Italy’s last survey, only four points lower than its peak in 2014. Income inequality has risen since 2008, showing almost no recovery in the last two years. The regional disparities in economic performance are even more concerning; income inequality recently was greatest in the south and islands and lowest in the central and northern regions of Italy. The traditionally well-off northern and the central regions received nearly 85 percent of all foreign direct investment leaving the south a mere 15 percent, showing a distinct gap in development and investor confidence. At the same time, the northern region currently has the highest GDP per capita, with the central part of the country following in second and the south standing at just above 21,000 euros, underscoring a substantial difference in the standards of living of Italians between regions.

We believe these economic indicators offer some insight into Italy’s upcoming elections. The inequality-stricken southern region is showing greater support for anti-establishment, largely Eurosceptic parties than the north. This rise in anti-establishment sentiment in Italy is mirrored across several advanced economies in the EU and beyond. Stagnant middle-class wages, rising income inequality, and growing economic uncertainty are economic forces that are pushing middle class voters toward anti-establishment parties. In Italy’s case, weaker support for establishment parties will likely result in a hung parliament, and increased political uncertainty for Italy in the near future. Political instability combined with stronger anti-EU voices in other member states could hamper structural reform efforts at the EU level aimed at improving the lives of all EU citizens.

Subscribe for more EconoGraphic content!